THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Actresses (Self) Fashioning

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE INTERNATIONAL STUDIES INTERDISCIPLINARY POLITICAL AND CULTURAL JOURNAL, Vol. 16, No. 1/2014 97–110, DOI: 10.2478/ipcj-2014-0007 ∗ Raquel Serrano González,* Laura Martínez-García* HOW TO REPRESENT FEMALE IDENTITY ON THE ∗∗ RESTORATION STAGE: ACTRESSES (SELF) FASHIONING ABSTRACT: Despite the shifting ideologies of gender of the seventeenth century, the arrival of the first actresses caused deep social anxiety: theatre gave women a voice to air grievances and to contest, through their own bodies, traditional gender roles. This paper studies two of the best-known actresses, Nell Gwyn and Anne Bracegirdle, and the different public personae they created to negotiate their presence in this all—male world. In spite of their differing strategies, both women gained fame and profit in the male—dominated theatrical marketplace, confirming them as the ultimate “gender benders,” who appropriated the male role of family’s supporter and bread-winner. KEY WORDS: Actresses, Restoration, Bracegirdle, Gwyn, gender notions, deployment of alliance, deployment of sexuality. Introduction: Men, Women and Changing Gender Notions The early seventeenth century was an eventful time for Britain, a moment when turmoil and war gave way to a strict regime, which then resulted in the return of peace and stability in the form of Parliamentary Monarchy. The 1600s saw two of the most significant events in the history of the British Isles: the Civil War and the execution of Charles I. ∗ University of Oviedo, Dpto. Filología Anglogermánica y Francesa Teniente Alfonso Martínez s/n 33011 – Oviedo (Asturias). E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ∗∗ We gratefully acknowledge financial suport from FICYT under the research grant Severo Ochoa (BP 10-028). -

My Lady Castlemaine

3XCY LjlDY CASTLEMJIINE <J c& Lady Castlemaine Being a Life of {Barbara 'Uilliers Countess of Castlemaine, afterwards Duchess of Cleveland :: By Philip W Sergeant, B.jl., Author of "The Empress Josephine, Napoleon's Enchantress," "'She Courtships of Catherine the Great," &c. With 19 Illustrations including a Photogravure Frontispiece DANA ESTES & CO. BOSTON Printed in Great Britain 5134844 PREFACE TT may perhaps be maintained that, if Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine and Duchess of Cleveland, has not been written about in many books, it is for a good and sufficient reason, that she is not worth writing about. That is not an argument to be lightly decided. But certainly less interesting women have been the subjects of numerous books, worse women, less influential and less beautiful than this lady of the dark auburn hair and deep blue eyes. We know that Mr. G. K. Chesterton says that Charles II attracts him morally. (His words are " attracts us," but this must be the semi-editorial " we.") If King Charles can attract morally Mr. Chesterton, may not his favourite attract others ? Or let us be repelled, and as we view the lady acting " her part at Whitehall let us exclaim, How differ- ent from the Court of ... good King William III," if we like. Undoubtedly the career of Barbara Villiers furnishes a picture of one side at least of life in the Caroline of the life of unfalter- period ; pleasure unrestrained, ing unless through lack of cash and unrepentant. For Barbara did not die, like her great rival Louise de " Keroualle (according to Saint-Simon), very old, V 2082433 vi PREFACE " and like very penitent, very poor ; or, another rival, Hortense Mancini (according to Saint-Evre- " mond), seriously, with Christian indifference toward life." On the principle bumani nil a me alienum puto even the Duchess of Cleveland cannot be con- sidered of attention as unworthy ; but, being more extreme in type, therefore more interesting than the competing beauties of her day. -

Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn As Life-Writing

This is a postprint! The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in Life Writing 13.4 (Taylor & Francis, 2016): 449-64. http://www.tandfonline.com/DOI: 10.1080/14484528.2015.1073715. ‘Rais’d from a Dunghill, to a King’s Embrace’: Restoration Verse Satires on Nell Gwyn as Life-Writing Dr. Julia Novak University of Salzburg Hertha Firnberg Research Fellow (FWF) Department of English and American Studies University of Salzburg Erzabt-Klotzstraße 1 5020 Salzburg AUSTRIA Tel. +43(0)699 81761689 Email: [email protected] This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Grant T 589-G23. Abstract Nell Gwyn (1650-1687), one of the very early theatre actresses on the Restoration stage and long-term mistress to King Charles II, has today become a popular cultural icon, revered for her wit and good-naturedness. The image of Gwyn that emerges from Restoration satires, by contrast, is considerably more critical of the king’s actress-mistress. It is this image, arising from satiric references to and verse lives of Nell Gwyn, which forms the focus of this paper. Creating an image – a ‘likeness’ – of the subject is often cited as one of the chief purposes of biography. From the perspective of biography studies, this paper will probe to what extent Restoration verse satire can be read as life-writing and where it can be situated in the context of other 17th-century life-writing forms. It will examine which aspects of Gwyn’s life and character the satires address and what these choices reveal about the purposes of satire as a form of biographical storytelling. -

Download Download

Early Modern Low Countries 1 (2017) 1, pp. 30-50 - eISSN: 2543-1587 30 ‘Before she ends up in a brothel’ Public Femininity and the First Actresses in England and the Low Countries Martine van Elk Martine van Elk is a Professor of English at California State University, Long Beach. Her research interests include early modern women, Shakespeare, and vagrancy. She is the author of numerous essays on these subjects, which have appeared in essay collections and in journals like Shakespeare Quarterly, Studies in English Literature, and Early Modern Women. Her book Early Modern Women’s Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Low Countries has been pub- lished by Palgrave Macmillan (2017). Abstract This essay explores the first appearance of actresses on the public stage in England and the Dutch Republic. It considers the cultural climate, the theaters, and the plays selected for these early performances, particularly from the perspective of public femininity. In both countries antitheatricalists denounced female acting as a form of prostitution and evidence of inner corruption. In England, theaters were commercial institutions with intimate spaces that capitalized on the staging of privacy as theatrical. By contrast, the Schouwburg, the only public playhouse in Amsterdam, was an institu- tion with a more civic character, in which the actress could be treated as unequivocally a public figure. I explain these differences in the light of changing conceptions of public and private and suggest that the treatment of the actress shows a stronger pub- lic-private division in the Dutch Republic than in England. -

Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1

European Journal of Educational Sciences, EJES March 2017 edition Vol.4, No.1 ISSN 1857- 6036 Teenage Pregnancy and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Behavior in Suhum, Ghana1 Charles Quist-Adade, PhD Kwantlen Polytechnic University doi: 10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 URL:http://dx.doi.org/10.19044/ejes.v4no1a1 Abstract This study sought to investigate the key factors that influence teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in-school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. While the data from the study provided a useful snapshot and a clear picture of sexual and reproductive behaviours of the teenagers surveyed, it did not point to any strong association between parental styles and teens’ sexual reproductive behaviours. Keywords: Parenting styles; parents; youth sexuality; premarital sex; teenage pregnancy; adolescent sexual and reproductive behavior. Introduction This research sought to present a more comprehensive look at teenage reproductive and sexual behaviours and how these behaviours are likely to be influenced by parenting styles of primary caregivers of adolescents in Suhum, in Eastern Ghana. The study aimed to identify risky sexual and reproductive behaviours and their underlying factors among in- school and out-of-school adolescents and how parenting styles might play a role. It was hypothesized that a balance of parenting styles is more likely to 1 Acknowledgements: I owe debts of gratitude to Ms. -

Darnley Portraits

DARNLEY FINE ART DARNLEY FINE ART PresentingPresenting anan Exhibition of of Portraits for Sale Portraits for Sale EXHIBITING A SELECTION OF PORTRAITS FOR SALE DATING FROM THE MID 16TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY On view for sale at 18 Milner Street CHELSEA, London, SW3 2PU tel: +44 (0) 1932 976206 www.darnleyfineart.com 3 4 CONTENTS Artist Title English School, (Mid 16th C.) Captain John Hyfield English School (Late 16th C.) A Merchant English School, (Early 17th C.) A Melancholic Gentleman English School, (Early 17th C.) A Lady Wearing a Garland of Roses Continental School, (Early 17th C.) A Gentleman with a Crossbow Winder Flemish School, (Early 17th C.) A Boy in a Black Tunic Gilbert Jackson A Girl Cornelius Johnson A Gentleman in a Slashed Black Doublet English School, (Mid 17th C.) A Naval Officer Mary Beale A Gentleman Circle of Mary Beale, Late 17th C.) A Gentleman Continental School, (Early 19th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Gerard van Honthorst, (Mid 17th C.) A Gentleman in Armour Circle of Pieter Harmensz Verelst, (Late 17th C.) A Young Man Hendrick van Somer St. Jerome Jacob Huysmans A Lady by a Fountain After Sir Peter Paul Rubens, (Late 17th C.) Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel After Sir Peter Lely, (Late 17th C.) The Duke and Duchess of York After Hans Holbein the Younger, (Early 17th to Mid 18th C.) William Warham Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller, (Early 18th C.) Head of a Gentleman English School, (Mid 18th C.) Self-Portrait Circle of Hycinthe Rigaud, (Early 18th C.) A Gentleman in a Fur Hat Arthur Pond A Gentleman in a Blue Coat -

Lord Henry Howard, Later 6Th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684)

THE WEISS GALLERY www.weissgallery.com 59 JERMYN STREET [email protected] LONDON, SW1Y 6LX +44(0)207 409 0035 John Michael Wright (1617 – 1694) Lord Henry Howard, later 6th Duke of Norfolk (1628 – 1684) Oil on canvas: 52 ¾ × 41 ½ in. (133.9 × 105.4 cm.) Painted c.1660 Provenance By descent to Reginald J. Richard Arundel (1931 – 2016), 10th Baron Talbot of Malahide, Wardour Castle; by whom sold, Christie’s London, 8 June 1995, lot 2; with The Weiss Gallery, 1995; Private collection, USA, until 2019. Literature E. Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 – 1790, London 1953, p.72, plate 66b. G. Wilson, ‘Greenwich Armour in the Portraits of John Michael Wright’, The Connoisseur, Feb. 1975, pp.111–114 (illus.). D. Howarth, ‘Questing and Flexible. John Michael Wright: The King’s Painter.’ Country Life, 9 September 1982, p.773 (illus.4). The Weiss Gallery, Tudor and Stuart Portraits 1530 – 1660, 1995, no.25. Exhibited Edinburgh, Scottish National Portrait Gallery, John Michael Wright – The King’s Painter, 16 July – 19 September 1982, exh. cat. pp.42 & 70, no.15 (illus.). This portrait by Wright is such a compelling amalgam of forceful assurance and sympathetic sensitivity, that is easy to see why that doyen of British art historians, Sir Ellis Waterhouse, described it in these terms: ‘The pattern is original and the whole conception of the portrait has a quality of nobility to which Lely never attained.’1 Painted around 1660, it is the prime original of which several other studio replicas are recorded,2 and it is one of a number of portraits of sitters in similar ceremonial 1 Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 to 1790, 4th integrated edition, 1978, p.108. -

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

R.Kirschbaum, Thesis, 2012.Pdf

Introduction: Female friendship, community and retreat Friendship still has been design‘d, The Support of Human-kind; The safe Delight, the useful Bliss, The next World‘s Happiness, and this. Give then, O indulgent Fate! Give a Friend in that Retreat (Tho‘ withdrawn from all the rest) Still a Clue, to reach my Breast. Let a Friend be still convey‘d Thro‘ those Windings, and that Shade! Where, may I remain secure, Waste, in humble Joys and pure, A Life, that can no Envy yield; Want of Affluence my Shield.1 Anne Finch’s “The Petition for an Absolute Retreat” is one of a number of verses by early modern women which engage with the poetic traditions of friendship and the pastoral.2 Finch employed the imagery and language of the pastoral to shape a convivial but protected space of retreat. The key to achieving the sanctity of such a space is virtuous friendship, which Finch implies is both enabled by and enabling of pastoral retirement. Finch’s retreat is not an absolute retirement; she calls for “a Friend in that Retreat / (Tho’ withdrawn from all the rest)” to share in the “humble Joys and pure” of the pastoral. Friendship is “design’d [as] the Support of Human-kind”, a divine gift to ease the burden of human reason and passion. The cause of “the next World’s Happiness, and this”, 1 Anne Finch, “The Petition for an Absolute Retreat” in Miscellany Poems, on Several Occasions, printed for J.B. and sold by Benj. Tooke at the Middle-Temple-Gate, William Taylor in Pater-Noster-Row, and James Round (London, 1713), pp. -

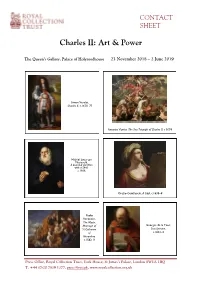

Charles II: Art & Power

CONTACT SHEET Charles II: Art & Power The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse 23 November 2018 – 2 June 2019 Simon Verelst, Charles II, c.1670–75 Antonio Verrio, The Sea Triumph of Charles II, c.1674 Michiel Jansz van Miereveld, A bearded old Man with a Shell, c.1606 Orazio Gentileschi, A Sibyl, c.1635–8 Paolo Veronese, The Mystic Marriage of Georges de la Tour, St Catherine Saint Jerome, of c.1621–3 Alexandria, c.1562–9 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk Cristofano Allori, Judith with the Parmigianino, Head of Pallas Athena, Holofernes, c.1531–8 1613 Sir Peter Lely, Sir Peter Lely, Barbara Villiers, Catherine of Duchess of Braganza, Cleveland, c.1663–65 c.1665 Pierre Fourdrinier, The Royal Palace of Holyrood House, Side table, c.1670 c.1753 Leonardo da Vinci, The muscles of the Hans Holbein the back and arm, Younger, Frances, c. 1508 Countess of Surrey, c.1532–3 Press Office, Royal Collection Trust, York House, St James’s Palace, London SW1A 1BQ T. +44 (0)20 7839 1377, [email protected], www.royalcollection.org.uk A selection of images is available at www.picselect.com. For further information contact Royal Collection Trust Press Office +44 (0)20 7839 1377 or [email protected]. Notes to Editors Royal Collection Trust, a department of the Royal Household, is responsible for the care of the Royal Collection and manages the public opening of the official residences of The Queen. -

Edward Hawke Locker and the Foundation of The

EDWARD HAWKE LOCKER AND THE FOUNDATION OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF NAVAL ART (c. 1795-1845) CICELY ROBINSON TWO VOLUMES VOLUME II - ILLUSTRATIONS PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART DECEMBER 2013 2 1. Canaletto, Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames, c.1752-3, NMM BHC1827, Greenwich. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 108.6 cm. 3 2. The Painted Hall, Greenwich Hospital. 4 3. John Scarlett Davis, The Painted Hall, Greenwich, 1830, NMM, Greenwich. Pencil and grey-blue wash, 14¾ x 16¾ in. (37.5 x 42.5 cm). 5 4. James Thornhill, The Main Hall Ceiling of the Painted Hall: King William and Queen Mary attended by Kingly Virtues. 6 5. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: King William and Queen Mary. 7 6. James Thornhill, Detail of the upper hall ceiling: Queen Anne and George, Prince of Denmark. 8 7. James Thornhill, Detail of the south wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of William III at Torbay. 9 8. James Thornhill, Detail of the north wall of the upper hall: The Arrival of George I at Greenwich. 10 9. James Thornhill, West Wall of the Upper Hall: George I receiving the sceptre, with Prince Frederick leaning on his knee, and the three young princesses. 11 10. James Thornhill, Detail of the west wall of the Upper Hall: Personification of Naval Victory 12 11. James Thornhill, Detail of the main hall ceiling: British man-of-war, flying the ensign, at the bottom and a captured Spanish galleon at top. 13 12. ‘The Painted Hall’ published in William Shoberl’s A Summer’s Day at Greenwich, (London, 1840) 14 13.