Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

Her Hour Upon the Stage: a Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1965 Her Hour Upon the Stage: A Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress Julie Ann Farrer Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Farrer, Julie Ann, "Her Hour Upon the Stage: A Study of Anne Bracegirdle, Restoration Actress" (1965). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2862. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2862 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HER HOUR UPON THE STAGE: A STUDY OF ANNE BRAC EGIRDLE, RESTORATION ACTRESS by Julie Ann Farrer A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis, in its final form, owes much to a number of willing people, without whose help the entire undertaking would be incomplete or else impossible. First thanks must go to Dr. Robert C. Steensma, chairman of my committee, and an invaluable source of help and encour agement throughout the entire year. I am also indebted to the members of my committee, Dr. Del Rae Christiansen and Dr. King Hendricks for valid and helpful suggestions . Appreciation is extended to Utah State University, to the English department and to Dr. Hendricks . I thank my understanding parents for making it possible and my friends for ma~ing it worthwhile . -

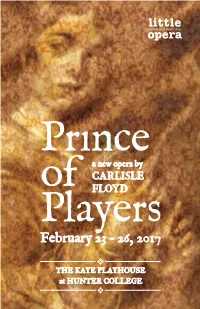

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “OTHELLO” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: 1603-1604…. although some critics place the date somewhat earlier in 1601- 1602 mainly on the basis of some “echoes” of the play in the 1603 “bad” quarto of “Hamlet”. AGE: 39-40 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Four years after “Hamlet”; first in the consecutive series of tragedies followed by “King Lear”, “Macbeth” then “Antony and Cleopatra”. GENRE: “The Great Tragedies” SOURCES: An Italian tale in the collection “Gli Hecatommithi” (1565) of Giovanni Battista Giraldi (writing under the name Cinthio) from which Shakespeare also drew for the plot of “Measure for Measure”. John Pory’s 1600 translation of John Leo’s “A Geographical History of Africa”; Philemon Holland’s 1601 translation of Pliny’s “History of the World”; and Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 “The Commonwealth and Government of Venice” mainly translated from a Latin text by Cardinal Contarini. STRUCTURE: “More a domestic tragedy than ‘Hamlet’, ‘Lear’ or ‘Macbeth’ concentrating on the destruction of Othello’s marriage and his murder of his wife rather than on affairs of state and the deaths of kings”. SUCCESS: The tragedy met with high success both at its initial Globe staging and well beyond mainly because of its exotic setting (Venice then Cypress), the “foregrounding of issues of race, gender and sexuality”, and the powerhouse performance of Richard Burbage, the most famous actor in Shakespeare’s company. HIGHLIGHT: Performed at the Banqueting House at Whitehall before King James I on 1 November 1604. AFTER: The play has been performed steadily since 1604; for a production in 1660 the actress Margaret Hughes as Desdemona “could have been the first professional actress on the English stage”. -

WRAP Theses Crowther 2017.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 97559 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications James Shirley and the Restoration Stage By Stefania Crowther A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Renaissance Studies University of Warwick, Centre for Renaissance Studies June 2017 2 3 Acknowledgements This thesis was supported by the James Shirley Complete Works Project, and funded by the AHRC, and Centre for Renaissance Studies, University of Warwick. I would like to thank these organisations, and in particular Jayne Browne, Ingrid de Smett, David Lines, Jayne Brown, Heather Pilbin, Paul Botley, and especially Elizabeth Clarke and Paul Prescott for their very helpful guidance during the upgrade process. Special thanks are due to Hannah Davis, whose URSS project on Restoration Shirley, supervised by Teresa Grant, provided the starting point for this thesis. I am also enormously grateful to the colleagues, friends and tutors who have inspired and supported my work: Daniel Ashman, Thomasin Bailey, Stephen Clucas, Michael Dobson, Peter Foreshaw, Douglas Hawes, Simon Jackson, Victoria Jones, Griff Jameson, Peter Kirwan, Chris Main, Gerry McAlpine, Zois Pigadas, Catherine Smith, Lee White, Susan Wiseman. -

'Prince of Players' Score Soars, While Libretto Is a Letdown

LIFESTYLE 'Prince of Players' score soars, while libretto is a letdown By Joseph Campana | March 7, 2016 0 Photo: Marie D. De Jesus, Staff Ben Edquist, plays the lead role Edward Kynaston, a famed actor in England in the 1700s whose career is abruptly stopped when the king issues a decree prohibiting men from playing women in stage roles. Armenian soprano Mane Galoyan will sing Margaret Hughes. The Houston Grand Opera (HGO) will present Prince of Players by distinguished American composer Carlisle Floyd on March 5, 11, and 13, 2016. ( Marie D. De Jesus / Houston Chronicle ) A night at the opera can leave us speechless or it can send us to our feet shouting "Bravo!" At the close of the Houston Grand Opera world premiere of Carlisle Floyd's "Prince of Players," it was all leaping and shouting. Floyd not only co-founded the Houston Grand Opera Studio, but this great American treasure has now premiered his fifth work for Houston Grand Opera just shy of his 90th birthday. That's plenty to celebrate. But the true achievement of "Prince of Players" is a beautifully realized production of an ambitious commission with an electrifying score stirringly conducted by Patrick Summers. From its opening moments, "Prince of Players" resounds with tonal unease, surreptitious woodwinds and warning strings. And in mere seconds, Floyd conveys that, in spite of some fun and flirtation to come, we are in the presence of a sea-change, and no one will remain unscathed. The marvel of Floyd is his attention to moments great and small. Some of the most compelling passages come seemingly between scenes or in the absence of voice - as an actor silently practices his gestures or as the court eerily processes before their king. -

"Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2011 "Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World Jarred Wiehe Columbus State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wiehe, Jarred, ""Play Your Fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through the Country Wife, the Man of Mode, the Rover, and the Way of the World" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 148. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/148 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/playyourfanexploOOwieh "Play your fan": Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage Through The Country Wife, The Man of Mode, The Rover, and The Way of the World By Jarred Wiehe A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program For Honors in the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In English Literature, College of Letters and Sciences, Columbus State University x Thesis Advisor Date % /Wn l ^ Committee Member Date Rsdftn / ^'7 CSU Honors Program Director C^&rihp A Xjjs,/y s z.-< r Date <F/^y<Y'£&/ Wiehe 1 'Play your fan': Exploring Hand Props and Gender on the Restoration Stage through The Country Wife, The Man ofMode, The Rover, and The Way of the World The full irony and wit of Restoration comedies relies not only on what characters communicate to each other, but also on what they communicate to the audience, both verbally and physically. -

Shakespeare and Gender: the ‘Woman’S Part’

Shakespeare and gender: the ‘woman’s part’ Article written by:Clare McManus Themes:Shakespeare’s life and world, Gender, sexuality, courtship and marriage Published:15 Mar 2016 In Shakespeare's day, female parts were played by male actors, while more recently, actresses have taken on some of his most famous male roles such as Hamlet and Julius Caesar. Clare McManus explores gender in the history of Shakespeare performance. Shakespearean performance is an arena for exploring desire, sexuality and gender roles and for challenging audience expectations, especially when it comes to the female performer. Actresses have long claimed their right to Olympian roles like Hamlet: Sarah Bernhardt’s 1899 performance sits in a long tradition, most recently added to by Maxine Peake in her performance at Manchester’s Royal Exchange in 2014. Bernhardt’s performance divided audiences: this was certainly at least partly to do with the crossing of gender boundaries, with one early London reviewer revealing how polarised ideas of gender could be when he complained that ‘A woman is positively no more capable of beating out the music of Hamlet than is a man of expressing the plaintive and half-accomplished surrender of Ophelia’.[1] That said, it had become increasingly common by the turn of the 20th century for star actresses to take male parts, often called ‘breeches’ roles, and it is possible that one difficulty for London audiences lay in the fact that Bernhardt’s Hamlet was not Shakespeare’s text but a prose translation. Over a century later, Maxine Peake’s interpretation was widely praised, though reviewers still focussed on the presence of a female actor in the role, contextualising it against the rich history of female Hamlets and interrogating the opportunities open to women in theatre in the early 21st century.[2] Postcard of Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet in 1899 The French actress, Sarah Bernhardt, crossed gender boundaries when she played the male hero in Hamlet. -

The Whore and the Breeches Role As Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Masked Criticism: the Whore and the Breeches Role as Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn. Mary Katherine Politz Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Politz, Mary Katherine, "Masked Criticism: the Whore and the Breeches Role as Articulators of Sexual Economic Theory in the Intrigue Plays of Aphra Behn." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7163. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7163 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. if Also,unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

10-Fr-736-Booklet-W.O. Crops

CARLISLE PRINCE OF FLOYD PLAYERS an oPera in two acts Phares royal Dobson shelton Kelley riDeout harms eDDy fr esh ! MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM BOGGS , CONDUCTOR FROM THE COMPOSER it is with great pleasure and pride that i congratulate the Florentine opera and soundmirror on this beautiful recording. it is the culmination of all the hard work and love that many people poured into making this opera a success. From its very beginning, Prince of Players has been a joy for me. back in 2011, i was flipping through tV channels and stopped on an interesting movie called staGe beauty, based on Jeffery hatcher’s play “the compleat Female stage beauty” and directed by sir richard eyre. the operatic potential struck me immediately. opera deals with crisis, and this was an enormous crisis in a young man’s life. i felt there was something combustible in the story, and that’s the basis of a good libretto. i always seek great emotional content for my operas and i thought this story had that. it is emotion that i am setting to music. if it lacks emotion, i know it immediately when i try to set it to music: nothing comes. From the story comes emotion, from the emotion comes the music. Fortunately for me, the story flowed easily, and drawing from the time-honored dramatic cycle of comfort, disaster, rebirth, i completed the libretto in less than two weeks. in 2013, the houston Grand opera commissioned Prince of Players as chamber opera, to be performed by its hGo studio singers, and staged by the young british director, michael Gieleta. -

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: the Survival of the London Theatre Community

Preservation and Innovation in the Intertheatrum Period, 1642-1660: The Survival of the London Theatre Community By Mary Alex Staude Honors Thesis Department of English and Comparative Literature University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2018 Approved: (Signature of Advisor) Acknowledgements I would like to thank Reid Barbour for his support, guidance, and advice throughout this process. Without his help, this project would not be what it is today. Thanks also to Laura Pates, Adam Maxfield, Alex LaGrand, Aubrey Snowden, Paul Smith, and Playmakers Repertory Company. Also to Diane Naylor at Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Much love to friends and family for encouraging my excitement about this project. Particular thanks to Nell Ovitt for her gracious enthusiasm, and to Hannah Dent for her unyielding support. I am grateful for the community around me and for the communities that came before my time. Preface Mary Alex Staude worked on Twelfth Night 2017 with Alex LaGrand who worked on King Lear 2016 with Zack Powell who worked on Henry IV Part II 2015 with John Ahlin who worked on Macbeth 2000 with Jerry Hands who worked on Much Ado About Nothing 1984 with Derek Jacobi who worked on Othello 1964 with Laurence Olivier who worked on Romeo and Juliet 1935 with Edith Evans who worked on The Merry Wives of Windsor 1918 with Ellen Terry who worked on The Winter’s Tale 1856 with Charles Kean who worked on Richard III 1776 with David Garrick who worked on Hamlet 1747 with Charles Macklin who worked on Henry IV 1738 with Colley Cibber who worked on Julius Caesar 1707 with Thomas Betterton who worked on Hamlet 1661 with William Davenant who worked on Henry VIII 1637 with John Lowin who worked on Henry VIII 1613 with John Heminges who worked on Hamlet 1603 with William Shakespeare.