Complete Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Temein Languages

Introduction to the Temein languages Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation CONVENTIONS I any high front vowel N any nasal T voiced dental or retroflex plosive 1. The Temein cluster The Temein cluster consists of three languages spoken in the Nuba Mountains, Sudan, NE of Kadugli. Little has been published on these languages, but Roland Stevenson (†) elicited substantial lexical data during the 1970s and 1980s, mostly from Khartoum-based informants 1. For further information about the Stevenson papers see Blench (1997). This paper is based on Stevenson’s material, on unpublished notes made by Gerrit Dimmendaal 2 and on SIL files in Khartoum which contain significant lexical data contributing towards a phonology of Tese (cf. also Yip 2004). 1 Following Roland Stevenson’s death in 1992, his mss. were dispersed for potential editing. The Temein data was held by Robin Thelwall but nothing came of this and in 2006, the documents were passed to me. Following a request by Tyler Schnoebelen of Stanford University, scans were made of the original datasheets with a view to typing the material. This was begun but had to be completed by Roger Blench in mid-2007. Stevenson’s originals can be downloaded from my website, as also the retyped data, re-arranged in a comparative format at http://www.rogerblench.info/Language%20data/Nilo- Saharan/Eastern%20Sudanic/Temein%20cluster/Temein%20page.htm 2 Thanks to Gerrit Dimmendaal for making his unpublished materials on Temein available. 1 Table 1 shows the three members of the Temein cluster with their ethnonyms and the names of the language: Table 1. -

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

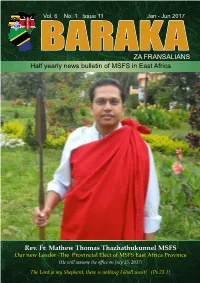

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning

The Role of Indigenous Languages in Southern Sudan: Educational Language Policy and Planning H. Wani Rondyang A thesis submitted to the Institute of Education, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2007 Abstract This thesis aims to questions the language policy of Sudan's central government since independence in 1956. An investigation of the root causes of educational problems, which are seemingly linked to the current language policy, is examined throughout the thesis from Chapter 1 through 9. In specific terms, Chapter 1 foregrounds the discussion of the methods and methodology for this research purposely because the study is based, among other things, on the analysis of historical documents pertaining to events and processes of sociolinguistic significance for this study. The factors and sociolinguistic conditions behind the central government's Arabicisation policy which discourages multilingual development, relate the historical analysis in Chapter 3 to the actual language situation in the country described in Chapter 4. However, both chapters are viewed in the context of theoretical understanding of language situation within multilingualism in Chapter 2. The thesis argues that an accommodating language policy would accord a role for the indigenous Sudanese languages. By extension, it would encourage the development and promotion of those languages and cultures in an essentially linguistically and culturally diverse and multilingual country. Recommendations for such an alternative educational language policy are based on the historical and sociolinguistic findings in chapters 3 and 4 as well as in the subsequent discussions on language policy and planning proper in Chapters 5, where theoretical frameworks for examining such issues are explained, and Chapters 6 through 8, where Sudan's post-independence language policy is discussed. -

Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9q7949gn Author Hansson, Gunnar Publication Date 2001 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony by Gunnar Ólafur Hansson B.A. (University of Iceland) 1993 M.A. (University of Iceland) 1997 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Sharon Inkelas (Chair) Professor Andrew Garrett Professor Larry M. Hyman Professor Alan Timberlake Spring 2001 The dissertation of Gunnar Ólafur Hansson is approved: Chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2001 Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony © 2001 by Gunnar Ólafur Hansson Abstract Theoretical and Typological Issues in Consonant Harmony by Gunnar Ólafur Hansson Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair The study of harmony processes, their phonological characteristics and parameters of typo- logical variation, has played a major role in the development of current phonological theory. Consonant harmony is a much rarer phenomenon than other types of harmony, and its typological properties are far less well known. Since consonant harmony often appears to involve assimilation at considerable distances, a proper understanding of its nature is crucial for theories of locality in segmental interactions. This dissertation presents a comprehensive cross-linguistic survey of consonant harmony systems. I show that the typology of such systems is quite varied as regards the properties that assimilate. -

Nilo-Saharan’

11 Linguistic Features and Typologies in Languages Commonly Referred to as ‘Nilo-Saharan’ Gerrit J. Dimmendaal, Colleen Ahland, Angelika Jakobi, and Constance Kutsch Lojenga 11.1 Introduction The phylum referred to today as Nilo- Saharan (occasionally also Nilosaharan) was established by Greenberg (1963). It consists of a core of language families already argued to be genetically related in his earlier classiication of African languages (Greenberg 1955:110–114), consisting of Eastern Sudanic, Central Sudanic, Kunama, and Berta, and grouped under the name Macrosudanic; this language family was renamed Chari- Nile in his 1963 contribution after a suggestion by the Africanist William Welmers. In his 1963 classiication, Greenberg hypothesized that Nilo- Saharan consists of Chari- Nile and ive other languages or language fam- ilies treated as independent units in his earlier study: Songhay (Songhai), Saharan, Maban, Fur, and Koman (Coman). Bender (1997) also included the Kadu languages in Sudan in his sur- vey of Nilo-Saharan languages; these were classiied as members of the Kordofanian branch of Niger-Kordofanian by Greenberg (1963) under the name Tumtum. Although some progress has been made in our knowledge of the Kadu languages, they remain relatively poorly studied, and there- fore they are not further discussed here, also because actual historical evi- dence for their Nilo- Saharan afiliation is rather weak. Whereas there is a core of language groups now widely assumed to belong to Nilo- Saharan as a phylum or macro- family, the genetic afiliation of families such as Koman and Songhay is also disputed (as for the Kadu languages). For this reason, these latter groups are discussed separately from what is widely considered to form the core of Nilo- Saharan, Central Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. -

From the Yellow Nile to the Blue Nile. the Quest for Water and the Diffusion of Northern East Sudanic Languages from the Fourth to the First Millenia BCE"

This lecture was delivered in ECAS 2009 (3rd European Conference on African Studies, Panel 142: African waters - water in Africa, barriers, paths, and resources: their impact on language, literature and history of people) in Leipzig, 4 to 7 June 2009. "From the Yellow Nile to the Blue Nile. The quest for water and the diffusion of Northern East Sudanic languages from the fourth to the first millenia BCE". Dr. Claude Rilly (CNRS-LLACAN, Paris) The quest for water and hence, for food supply, is a key issue in the appearance and diffusion of languages in the Sahelian regions of Africa. Climate changes, as occurred from the end of Neolithic period down to the second millenium BCE, played a major role in the redistribution of populations along the Nile river and its tributaries and can explain the appearance of a recently defined linguistic family, namely Northern East Sudanic (NES). This paper must be considered as a synthesis of several recent publications I wrote on this subject, so that I shall have to refer the reader, more often than not, to these earlier studies. Detailed demonstration of all these points would require much more time than is allotted to me. The Northern East Sudanic language group In his seminal study published in 1963, J. H. Greenberg divided the languages of Africa into four major phyla or superfamilies, namely Afroasiatic, Niger-Congo, Khoisan and Nilo-Saharan. If the three first phyla were more or less obvious, Nilo-Saharan was not so easily constituted, requiring from Greenberg a long work to merge twelve different families into one phylum. -

Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda

Sub–Saharan Africa Transport Policy Program The World Bank and Economic Commission for Africa SSATP Working Paper No 12 Case Study on Intermediate Means of Transport Bicycles and Rural Women in Uganda Christina Malmberg Calvo February 1994 Environmentally Sustainable Development Division Africa Region The World Bank Foreword One of the objectives of the Rural Travel and Transport Project (RTTP) is to recommend approaches for improving rural transport, including the adoption of intermediate transport technologies to facilitate goods movement and increase personal mobility. For this purpose, comprehensive village-level travel and transport surveys (VLTTS) and associated case studies have been carried out. The case studies focus on the role of intermediate means of transport (IMT) in improving mobility and the role of transport in women's daily lives. The present divisional working paper is the second in a series reporting on the VLTTS. The first working paper focussed on travel to meet domestic needs (for water, firewood, and food processing needs), and on the impact on women of the provision of such facilities as water supply, woodlots, fuel efficient stoves and grinding mills. The present case study documents the use of bicycles in eastern Uganda where they are a means of generating income for rural traders and for urban poor who work as bicycle taxi-riders. It also assesses women's priorities regarding interventions to improve mobility and access, and the potential for greater use of bicycles by rural women and for women's activities. The bicycle is the most common IMT in SSA, and it is used to improve the efficiency of productive tasks, and to serve as a link between farms and villages, nearby road networks, and market towns. -

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages

Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Historical Linguistics and the Comparative Study of African Languages Gerrit J. Dimmendaal University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American 8 National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dimmendaal, Gerrit Jan. Historical linguistics and the comparative study of African languages / Gerrit J. Dimmendaal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. African languages--Grammar, Comparative. 2. Historical linguistics. I. Title. PL8008.D56 2011 496--dc22 2011002759 isbn 978 90 272 1178 1 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 1179 8 (Pb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 8722 9 (Eb) © 2011 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Company • P.O. Box 36224 • 1020 me Amsterdam • The Netherlands John Benjamins North America • P.O. Box 27519 • Philadelphia PA 19118-0519 • USA UNCORRECTED PROOFS © JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY 1st proofs Table of contents Preface ix Figures xiii Maps xv Tables -

Monolingualism Via Multilingualism: a Case Study of Language Use in the West Ugandan Town of Hoima

African Study Monographs, 34 (1): 1–25, March 2013 1 MONOLINGUALISM VIA MULTILINGUALISM: A CASE STUDY OF LANGUAGE USE IN THE WEST UGANDAN TOWN OF HOIMA Shigeki KAJI Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University ABSTRACT Multilingualism is one of the most salient features of language use in Africa and, at first sight, Uganda appears to be just one example of this practice. However, as Uganda has no lingua franca that is widely used by its entire population, questions about how people cope with multilingualism arise. Answers to such questions can be found in the fact that people are able to create a monolingual state in a given area because everyone is multilingual. That is, people speak their own language in their own domain and speak other peoples’ languages when they go to the latter’s domains. This conclusion emerged from interviews conducted with 100 inhabitants of Hoima city in western Uganda, an area primarily inhabited by the Nyoro people. The linguistic situation in Hoima provides a valuable case study of what can happen in the absence of a fully developed lingua franca and can contribute to broader discussions of language use in Africa. Key Words: Lingua franca; Multilingualism; Hoima; Nyoro; Uganda. INTRODUCTION I have conducted linguistic research in Uganda since 2001. The main themes of my research relate to the grammatical and lexical characteristics of little-known languages in the area. In the course of research, however, I noticed differences between the use of language in Uganda and that in the regions where I had studied before. -

Kasujja EDU ARTICLE 2012

Ethnocentrism and National Elections in Uganda John Paul Kasujja, Anthony Muwagga Mugagga The paper focuses on ethnocentrism as an active factor for national election turmoil in Uganda. The bewitchment of the military by ethnocentric virus, the subsequent coups and overthrows, to the military regimes and dictatorships by successive presidents since 1966, the 1980, 1996, 2001 and 2006 presidential elections, can account for ethnocentric tendencies in the Pearl of Africa. Thereafter, the paper discusses the 1996, 2001 and 2006 general elections held in Uganda before propounding implications for the country’s future. Keywords : Ethnocentrism, Politics and development, Elections Introduction Uganda is in the easterly region of the African continent with a diverse ethnic composition. It borders Kenya in the East, Democratic republic of Congo in the west, Southern Sudan in the north and Tanzania in the south, Ssekamwa (1994). The area has attracted almost every ethnic group for settlement and business, and this has sensitized ethnocentrism among the settlers. This trait has been practiced in the politics of the state especially in national elections. Ethnocentrism exists in most countries across borders, but how it affects the political endeavours of a state with multi-ethnic populations vary. For the case of Uganda, ethnic differences make a significant impact on political activity, like national elections. The awareness of these differences has been referred to as “tribalism”, or ethnicity. The term ethnocentrism is a commonly used word in circles where ethnicity, inter ethnic relations and similar social issues are of concern. Its definition is “thinking one’s, group’s ways as superior to others”, or “judging other groups as inferior to one’s own”, K. -

A Grammar of Luwo Culture and Language Use Studies in Anthropological Linguistics

A Grammar of Luwo Culture and Language Use Studies in Anthropological Linguistics CLU-SAL publishes monographs and edited collections, culturally oriented grammars and dictionaries in the cross- and interdisciplinary domain of anthropological linguistics or linguistic anthropology. The series offers a forum for anthropological research based on knowledge of the native languages of the people being studied and that linguistic research and grammatical studies must be based on a deep understanding of the function of speech forms in the speech community under study. For an overview of all books published in this series, please see http://benjamins.com/catalog/clu Editor Gunter Senft Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen Volume 12 A Grammar of Luwo. An anthropological approach by Anne Storch A Grammar of Luwo An anthropological approach Anne Storch University of Cologne John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 the American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Storch, Anne. A Grammar of Luwo : An anthropological approach / Anne Storch. p. cm. (Culture and Language Use, issn 1879-5838 ; v. 12) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Luwo language (South Sudan)--Grammar. 2. Luwo language (South Sudan)--Parts of speech. 3. Anthropological linguistics. I. Title. PL8143.S76 2014 496’.5--dc23 2014027010 isbn 978 90 272 0295 6 (Hb ; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 6937 9 (Eb) © 2014 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher.