Spiritual Pollution, Time, and Other Uncertainties in Acholi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Uganda National a Uganda National Roads Authority

Rethinking the Big Picture of UNRA’s Business ROADS AUTHORITY(UNRA) UGANDA NATIONAL JUNE 2012 2012/13 – 2016/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Content Page Section Content Page 11 SWOT Analysis 1 Message from the UNRA 03 21 Chairperson & Board 2 Message from the Executive 04 12 PEST Analysis Director 27 3 Background 05 13 Critical Success Factors 29 4 Introduction 08 14 Business Context 31 5 UNRA Strategy Translation 11 Process 15 Grand Strategy 36 6 UNRA Va lue Cha in 12 16 Grand Strategy Map 37 7 Mission Statement 13 17 Goals and Strategies 8 Corporate Values 14 39 18 Implementing and 9 Assumptions 15 Monitoring the Plan 51 10 Vision Statement 19 19 Programme of Key Road Development Activities 53 2 SECTION 1. Message from the Chairperson Dear Staff at UNRA, In return, the Board will expect higher It is with great privilege and honour that I write to performance and greater accountability from thank you for your participation in the defining for Management and staff. Everyone must play his the firs t time the Stra teg ic Direc tion UNRA will t ak e role in delivering on the goals set in this over the coming 5 years. On behalf of the UNRA strategic plan. The proposed performance Board of Directors, I salute you for this noble effort. measurement framework will provide a vital tool for assessing progress towards to achievement The Strategic Plan outlines a number of strategic of the set targets. options including facilitating primary growth sectors (agriculture, industry, mining and tourism), Let me take this opportunity to appeal to improving the road condition, providing safe roads everyone to support the ED in implementing this and ensuring value for money. -

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

The Development of Law in Uganda*

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 5 | Number 1 Article 2 1983 Autochthony: The evelopmeD nt of Law in Uganda Francis M. Ssekandi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ssekandi, Francis M. (1983) "Autochthony: The eD velopment of Law in Uganda," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol5/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW Volume 5 Number 1 1983 AUTOCHTHONY: THE DEVELOPMENT OF LAW IN UGANDA* FRANCIS M. SSEKANDI** * This is the text of an address delivered at the Law Development Centre in Kampala, Uganda in July 1979, barely three months after the Ugandan Liberation Forces, composed of exiles and led by the Tanzania Defence Forces, booted Idi Amin out of Uganda. An interim government led by Yusufu Lule had assumed office and there was a lively debate in the air on the future of the Ugandan Constitution. Historically, Uganda was ruled by the British as a Protectorate, from 1890 with a measure of internal autonomy for the inhabitants, through a series of "treaties" with the kings of the territories from which Uganda was carved. Thus, on attainment of independence in 1962, the country emerged as a federation of its constituent parts. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 490 | FEBRUARY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE w w w .usip.org North Korea in Africa: Historical Solidarity, China’s Role, and Sanctions Evasion By Benjamin R. Young Contents Introduction ...................................3 Historical Solidarity ......................4 The Role of China in North Korea’s Africa Policy .........7 Mutually Beneficial Relations and Shared Anti-Imperialism..... 10 Policy Recommendations .......... 13 The Unknown Soldier statue, constructed by North Korea, at the Heroes’ Acre memorial near Windhoek, Namibia. (Photo by Oliver Gerhard/Shutterstock) Summary • North Korea’s Africa policy is based African arms trade, construction of owing to African governments’ lax on historical linkages and mutually munitions factories, and illicit traf- sanctions enforcement and the beneficial relationships with African ficking of rhino horns and ivory. Kim family regime’s need for hard countries. Historical solidarity re- • China has been complicit in North currency. volving around anticolonialism and Korea’s illicit activities in Africa, es- • To curtail North Korea’s illicit activ- national self-reliance is an under- pecially in the construction and de- ity in Africa, Western governments emphasized facet of North Korea– velopment of Uganda’s largest arms should take into account the histor- Africa partnerships. manufacturer and in allowing the il- ical solidarity between North Korea • As a result, many African countries legal trade of ivory and rhino horns and Africa, work closely with the Af- continue to have close ties with to pass through Chinese networks. rican Union, seek cooperation with Pyongyang despite United Nations • For its part, North Korea looks to China, and undercut North Korean sanctions on North Korea. -

Erin's Guide to Gulu

Edited 10/2019 GHCE Global Health Clinical Elective 2020 GUIDE TO YOUR CLINICAL ELECTIVE IN Gulu, UGANDA Disclaimer: This booklet is provided as a service to UW students going to Gulu, Uganda, based on feedback from previous students. The Global Health Resource Center is not responsible for any inaccuracies or errors in the booklet's contents. Students should use their own common sense and good judgment when traveling, and obtain information from a variety of reliable sources. Please conduct your own research to ensure a safe and satisfactory experience. TABLE OF CONTENTS Contact Information 3 Entry Requirements 5 Country Overview 6 Packing Tips 8 Money 13 Communication 13 Travel to/from Gulu 14 Phrases 16 Food 16 Budgeting 17 Fun 17 Health and Safety Considerations 18 How not to make an ass of yourself 19 Map 21 Cultural Adjustment 24 Guidelines for the Management of Body Fluid Exposure 26 2 CONTACT INFORMATION - U.S. Name Address Telephone Email or Website UW In case of emergency: +1-206-632-0153 www.washington.edu/glob International 1. Notify someone in country (24-hr hotline) alaffairs/emergency/ Emergency # 2. Notify CISI (see below) 3. Call 24-hr hotline [email protected] 4. May call Scott/McKenna [email protected] GHCE Director(s) Dr. Scott +206-473-0392 [email protected] McClelland (Scott, cell) [email protected] 001-254-731- Dr. McKenna 490115 (Scott, Eastment Kenya) GHRC Director Daren Wade Harris Hydraulics +1-206-685-7418 [email protected] (office) Building, Room [email protected] #315 +1-206-685-8519 [email protected] 1510 San Juan (fax) Road Seattle, WA 98195 Insurance CISI 24/7 call center [email protected] available at 888-331- nce.com 8310 (toll-free) or 240-330-1414 (accepts Collect calls) Hall Health Anne Terry, 315 E. -

[email protected] Prayer of Devotion to Fr

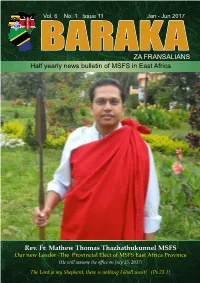

Vol. 6 No. 1 Issue 11 Jan - Jun 2017 %$5$.ZA FRANSALIANS$ Half yearly news bulletin of MSFS in East Africa Rev. Fr. Mathew Thomas Thazhathukunnel MSFS Our new Leader -The Provincial Elect of MSFS East Africa Province (He will assume the office on July 15, 2017) The Lord is my Shepherd, there is nothing I shall want! (Ps.23.1) Sisters of the Cross in East Africa Raised to the status of an Independent New Province East Africa Province Congratulations!!! The Congregation of the Sisters of the Cross, generally known as Holy Cross Sisters of Chavanod, was founded in the year 1838 at Chavanod in France. Together with Mother Claudine Echernier as the Foundress, Fr. Peter Marie Mermier (also the Founder of Missionaries of St. Francis de Sales) founded the Congregation with: The Vision “Make the Good God known and loved” & The Mission “Reveal to all the Merciful Love of the Father and the liberating power of the Paschal Mystery.” Today the members are working in three continents in 15 countries. Holy Cross Sisters from India landed in East Afri- ca - Tanzania in 1979. In 1996 the mission unit was raised to the status of a Delegation. On April 26, 2017 the Delegation was raised to the Status of a Province. The first Provincial of this new born Province Sr. Lucy Maliekal assumed the office on the same day. At present the Province head quarters is at Mtoni Kijichi, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Now the Province has 52 professed members of whom 40 are from East Africa and 12 are from India. -

Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda

Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda: A Case Study of the Acholi and Lango Sub-Regions Shilpi Shabdita Okwir Isaac Odiya Mapping Regional Reconciliation in Northern Uganda © 2015, Justice and Reconciliation Project, Gulu, Uganda All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: Justice and Reconciliation Project Plot 50 Lower Churchill Drive, Laroo Division P.O. Box 1216 Gulu, Uganda, East Africa [email protected] Layout by Lindsay McClain Opiyo Front cover photo by Shilpi Shabdita Printed by the Justice and Reconciliation Project, Gulu, Uganda This publication was supported by a grant from USAID SAFE Program. However, the opinions and viewpoints in the report is not that of USAID SAFE Program. ii Justice and Reconciliation Project Acknowledgements This report was made possible with a grant from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Supporting Access to Justice, Fostering Equity and Peace (SAFE) Program for the initiation of the year-long project titled, “Across Ethnic Boundaries: Promoting Regional Reconciliation in Acholi and Lango Sub-Regions,” for which the Justice and Reconciliation Project (JRP) gratefully acknowledges their support. We are deeply indebted to Boniface Ojok, Head of Office at JRP, for his inspirational leadership and sustained guidance in this initiative. Special thanks to the enumerators Abalo Joyce, Acan Grace, Nyeko Simon, Ojimo Tycoon, Akello Paska Oryema and Adur Patritia Julu for working tirelessly to administer the opinion survey and to collect data, which has formed the blueprint of this report. -

The Project for Community Development for Promoting Return and Resettlement of Idp in Northern Uganda

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER AMURU DISTRICT/ NWOYA DISTRICT THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE PROJECT FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT FOR PROMOTING RETURN AND RESETTLEMENT OF IDP IN NORTHERN UGANDA FINAL REPORT MARCH 2011 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NTC INTERNATINAL CO., LTD. EID JR 11-048 Uganda Amuru Location Map of Amuru and Nwoya Districts Location Map of the Target Sites PHOTOs Urgent Pilot Project Amuru District: Multipurpose Hall Outside View Inside View Handing over Ceremony (December 21 2010) Amuru District: Water Supply System Installation of Solar Panel Water Storage facility (For solar powered submersible pump) (30,000lt water tank) i Amuru District: Staff house Staff House Local Dance Team at Handing over Ceremony (1 Block has 2 units) (October 27 2010) Pabbo Sub County: Public Hall Outside view of public hall Handing over Ceremony (December 14 2010) ii Pab Sub County: Staff house Staff House Outside View of Staff House (1 Block has 2 units) (4 Block) Pab Sub County: Water Supply System Installed Solar Panel and Pump House Training on the operation of the system Water Storage Facility Public Tap Stand (40,000lt water tank) (5 stands; 4tap per stand) iii Pilot Project Pilot Project in Pabbo Sub-County Type A model: Improvement of Technical School Project Joint inspection with District Engineer & Outside view of the Workshop District Education Officer Type B Model: Pukwany Village Improvement of Access Road Project River Crossing After the Project Before the Project (No crossing facilities) (Pipe Culver) Road Rehabilitation Before -

Songs of Soldiers

SONGS OF SOLDIERS DECOLONIZING POLITICAL MEMORY THROUGH POETRY AND SONG by Juliane Okot Bitek BFA, University of British Columbia, 1995 MA, University of British Columbia, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Interdisciplinary Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2019 © Juliane Okot Bitek, 2019 ii The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Songs of Soldiers: Decolonizing Political Memory Through Poetry And Song submitted by Juliane Okot Bitek in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Interdisciplinary Studies Examining Committee: Prof. Pilar Riaño-Alcalá, (Social Justice) Co-supervisor Prof. Erin Baines, (Public Policy, Global Affairs) Co-supervisor Prof. Ashok Mathur, (graduate Studies) OCAD University, Toronto Supervisory Committee Member Prof. Denise Ferreira da Silva (Social Justice) University Examiner Prof. Phanuel Antwi (English) University Examiner iii Abstract In January 1979, a ship ferrying armed Ugandan exiles and members of the Tanzanian army sank on Lake Victoria. Up to three hundred people are believed to have died on that ship, at least one hundred and eleven of them Ugandan. There is no commemoration or social memory of the account. This event is uncanny, incomplete and yet is an insistent memory of the 1978-79 Liberation war, during which the ship sank. From interviews with Ugandan war veterans, and in the tradition of the Luo-speaking Acholi people of Uganda, I present wer, song or poetry, an already existing form of resistance and reclamation, as a decolonizing project. -

African Music Vol 7 No 4(Seb)

XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF BUSOGA 29 XYLOPHONE MUSIC OF UGANDA: THE EMBAIRE OF NAKIBEMBE, BUSOGA by JAMES MICKLEM, ANDREW COOKE & MARK STONE In search of xylophones1 B u g a n d a The amadinda and akadinda xylophone music of Buganda1 2 have been well described in the past (Anderson 1968). Good players of these xylophones now seem to be extremely scarce, and they are rarely performed in Kampala. Both instruments, although brought from villages in Buganda, formed part of a great musical tradition associated with the Kabaka’s palace. After 1966, when the palace was overrun by government forces and the kingdom abolished, the royal musicians were cut off from their traditional role. It is not clear how many of the former palace amadinda players still survive. Mr Kyobe, at Namaliri Trading Centre and his brothers Mr Wilson Sempira Kinonko and Mr Edward Musoke, Kikuli village, are still fine players with extensive knowledge of the amadinda xylophone repertoire, and the latter have been teaching their skills in Kikuli. As for the akadinda, P.Cooke reports (1996) that a 1987 visit found it was still being taught and played in the two villages where the palace players used to live A xylophone which has become popular in wedding music ensembles is sometimes also known by the name amadinda, but this is smaller, often with only 9 keys, and is played by only a single player in a style called ssekinomu. Otherwise, xylophones are used at teaching institutions in Kampala, but they are rarely performed. Indeed, it is difficult to find a well-made xylophone anywhere in Kampala. -

Lord's Resistance Army

Lord’s Resistance Army Key Terms and People People Acana, Rwot David Onen: The paramount chief of the Acholi people, an ethnic group from northern Uganda and southern Sudan, and one of the primary targets of LRA violence in northern Uganda. Bigombe, Betty: Former Uganda government minister and a chief mediator in peace negotiations between the Ugandan government and the LRA in 2004-2005. Chissano, Joaquim: Appointed as Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General to Northern Uganda and Southern Sudan in 2006; now that the internationally-mediated negotiations Joseph Kony, “ultimate commander” of the with the LRA have stalled, Chissano’s role as Special Envoy in the process is unclear. Lord’s Resistance Army/ photo courtesy of Radio France International, taken in the spring of 2008 during the failed Juba Kabila, Joseph: President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Peace Talks. Kony, Joseph: Leader of the LRA. Kony is a self-proclaimed messiah who led the brutal, mystical LRA movement in its rebellion against the Ugandan gov- ernment for over two decades. A war criminal wanted by the International Criminal Court, Kony remains the “ultimate commander” of the LRA, and he determines who lives and dies within the rebel group as they continue their predations today throughout central Africa. Lakwena, Alice Auma: Leader of the Holy Spirit Mobile Forces, a northern based rebel group that fought against the Ugandan government in the late 1980s. Some of the followers of this movement were later recruited into the LRA by Joseph Kony. Lukwiya, Raska: One of the LRA commanders indicted by the ICC in 2005.