The Development of Law in Uganda*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

Living with AIDS in Uganda

Living with AIDS in Uganda Impacts on banana-farming households in two districts Monica Karuhanga Beraho Living with AIDS in Uganda Impacts on banana-farming households in two districts Monica Karuhanga Beraho binnenwerk AWLAE6 officieel.indd1 1 18-12-2007 16:40:34 Promotor Prof. Dr. A. Niehof Hoogleraar Sociologie van Consumenten en Huishoudens Co-promotor Dr. P. Hebinck Universitair hoofddocent, leerstoelgroep Rurale Ontwikkelingssociologie Promotiecommissie Prof. Dr. J.D. Van der Ploeg Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. P.L. Geschiere Universiteit van Amsterdam Dr. T.R. Müller University of Manchester, UK Prof. Dr. G.E. Frerks Wageningen Universiteit Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd binnen de onderzoeksschool Mansholt Graduate School of Social Sciences Living with AIDS in Uganda Impacts on banana-farming households in two districts Monica Karuhanga Beraho Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor op gezag van de rector magnificus van Wageningen Universiteit Prof. Dr. M.J. Kropff in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 18 januari 2008 des morgens om 11.00 uur in de Aula Living with AIDS in Uganda: Impacts on banana-farming households in two districts Monica Karuhanga Beraho Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University (2008) With references – With summaries in English and Dutch ISBN 978-90-8504-817-6 ISBN 978-90-8686-064-7 Acknowledgements I am highly indebted to several individuals and organizations without whose support it would not have been possible to accomplish my PhD studies. This PhD study was funded by the Netherlands government through AWLAE (African Women Leaders in Agriculture and Environment), a program of Winrock International, for which am deeply thankful. -

Uganda Constitutional Instruments

UGANDA GOVERNMENT U o- A ^ d-d,, 0-ùi ' 67//7i/7 à A) , UGANDA CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENTS The Uganda (Independence) Order in Council, 1962 and The Constitution of Uganda (excluding Schedules I to 6) in force on THE 31st DECEMBER, 1963 Printed and published by the Government Printer, Entebbe under the Authority of the Government of Uganda UGANDA CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENTS The Uganda (Independence) Order in Council, 1962 and The Constitution of Uganda (excluding Schedules I to 6) LOS ANGELES COUNTY LAW LIBRARY PREFACE THIS BOOKLET, which is intended to be used in conjunction with the edition of the Constitutional Instruments published in 1962, contains the Uganda (Independence) Order in Council, 1962, and the Constitution of Uganda, as in force on the 31st December, 1963. Where it appears that any provision of the Order in Council is spent or is not likely to be the subject of more than an occasional reference in the future, the provision in question has been printed in italics. This has been done merely for convenience. These provisions have not been repealed, and remain part of the Order. It has not been possible to include in this booklet Schedules 1 to 6 of the Constitution. For these Schedules, which contain the Constitution of Buganda, the special provisions for the other Federal States and the procedure for the election of members of the National Assembly from Buganda by the Lukiiko, it will still be necessary to refer to the 1962 edition of the Constitutional Instruments. G. L. BINAISA, Attorney-General. ENTEBBE, 30TH JANUARY, 1964. THE UGANDA (INDEPENDENCE) ORDER IN COUNCIL, 1962 ARRANGEMENT OF ORDER. -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Download/Speech%20Moreno.Pdf> Accessed September 10, 2013

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Ruhweza, Daniel Ronald (2016) Situating the Place for Traditional Justice Mechanisms in International Criminal Justice: A Critical Analysis of the implications of the Juba Peace Agreement on Reconciliation and Accountability. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/56646/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Situating the Place for Traditional Justice Mechanisms in International Criminal Justice: A Critical Analysis of the implications of the Juba Peace Agreement on Reconciliation and Accountability By DANIEL RONALD RUHWEZA Supervised by Dr. Emily Haslam, Prof. Toni Williams & Prof. Wade Mansell A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Award of the Doctor of Philosophy in Law (International Criminal Law) at University of Kent at Canterbury April 2016 DECLARATION I declare that the thesis I have presented for examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Kent at Canterbury is exclusively my own work other than where I have evidently specified that it is the work of other people. -

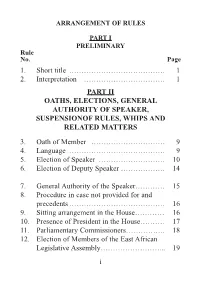

1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY of SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS and RELATED MATTERS 3

ARRANGEMENT OF RULES PART I PRELIMINARY Rule No. Page 1. Short title………………………………… 1 2. Interpretation …………………………… 1 PART II OATHS, ELECTIONS, GENERAL AUTHORITY OF SPEAKER, SUSPENSIONOF RULES, WHIPS AND RELATED MATTERS 3. Oath of Member ………………………… 9 4. Language ………………………………… 9 5. Election of Speaker ……………………… 10 6. Election of Deputy Speaker ……………… 14 7. General Authority of the Speaker………… 15 8. Procedure in case not provided for and precedents………………………………… 16 9. Sitting arrangement in the House………… 16 10. Presence of President in the House………. 17 11. Parliamentary Commissioners……………. 18 12. Election of Members of the East African Legislative Assembly……………………... 19 i Rule No. Page 13. Election of Members of Pan African Parliament………………………………… 20 14. Role and functions of the Leader of the Opposition ………………………… 20 15. Whips……………………………………… 21 16. Suspension of Rules ……………………… 23 PART III MEETINGS, SITTINGS AND ADJOURNMENT OF THE HOUSE 17. Meetings ………………………………… 24 18. Emergency meetings……………………… 24 19. Sittings of the House……………………… 24 20. Suspension of sittings and recall of House from adjournment ………………… 25 21. Request for recall of Parliament from recess 26 22. Public holidays …………………………… 26 23. Sittings of the House to be public………... 26 24. Quorum of Parliament …………………… 27 PART IV ORDER OF BUSINESS 25. Order of business ………………………… 29 26. Procedure of Business …………………… 31 ii Rule No. Page 27. Order Paper to be sent in advance to Members ………………………………… 32 28. Statement of business by Leader of Government Business …………………… 33 29. Weekly Order Paper ……………………… 33 PART V PETITIONS 30. Petitions…………………………………… 34 PART VI PAPERS 31. Laying of Papers ………………………… 37 32. Mode of Laying of Papers………………… 37 PART VII PRESENTATION OF REPORTS OF PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATIONS ABROAD 33. -

Reconstituting Ugandan Citizenship Under the 1995 Constitution

Mission of the Centre for Basic Research To generate and disseminate knowledge by conducting basic and applied research of social, economic and political significance to Uganda in particular and Africa in general so as to influence policy, raise consciousness and improve quality of life. Reconstituting Ugandan Citizenship Under the 1995 Constitution: A Conflict of Nationalism, Chauvinism and Ethnicity John-Jean B. Barya Working Paper No.55/2000 ISBN:9970-516-41-4 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... Section I: The Concept of Citizenship and its Significance in the 1995 Constitution ................................................................ Section II: From British Protected Persons to Ugandan Citizens 1949-1967 ............................................................................. Section III:1 Who is a Citizen of Uganda? ........................................................................... Section N: The Citizenship Debate: Lessons and Conclusions ........................................................................................................ Bibliography ................................................................. ' . Reconstituting Ugandan Citizenship Under the 1995 Constitution: A Conflict of Nationalism, Chauvinism and Ethnicity* Introduction Citizenship for any person in the contemporary world situation is a very important concept; a concept that most of the time determines the very -

Odoki, B. Challenges of Constitution-Making in Uganda

264 ConstiiuIioaalis,,i ii, Africa 15 challenge in courts of law. The controversialprovisionsmainlyrelate to the politicalsystemespecially the issue ofsuspension ofpoliticalpartyactivities, TheChallenges ofConstitution-makingand thereferendum on politicalsystems, the entrenchmentofthemovementsystem in the constitution,federalism, and the issue of land. in Implementation Uganda The implementation of the constitutionposesperhapsmore difficult challengesthan its making.There is a need to make theconstitution a dynamic Benjamin J. Odoki instrument, and a livinginstitution, in the minds and hearts of all Ugandans. Theconstitutionmust be iiiternalised and understood in order for the people to trulyrespect,observe and uphold it. It must be implemented in both the and to the letter.There is a need to establish and nurturedemocratic Themaking of a newconstitution in Ugandamarked an importantwatershed in spirit the history of the country. It demonstrated the desire of the people to institutions to promotedemocraticvalues andpracticeswithin the country. It is then that a culture of constitutionalism can be the fundamentallychange their system of governance into a truly democratic only promotedamongst and theirleaders. one. The process gave the people an opportunity to make a fresh start by people This examines the and that reviewingtheirpastexperiences,identifying the rootcauses oftheirproblems, chapter challenges problems wereexperienced the actors in the theNRM learninglessonsfrompastmistakesandmaking a concertedeffort to provide by major constitution-makingprocess: -

Adminstrative Law and Governance Project Kenya, Malawi and Uganda

LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN UGANDA By Rose Nakayi ADMINSTRATIVE LAW AND GOVERNANCE PROJECT KENYA, MALAWI AND UGANDA The researcher acknowledges the research assistance offered by James Nkuubi and Brian Kibirango 1 Contents I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 3 II. LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT............................................................. 6 A. Local Governance in the Pre-Independence Period ........................................................................... 6 B. Rule Making, Public Participation and Accountability in Pre independence Uganda ....................... 10 C. The Post-Independence Period........................................................................................................ 11 D. Post 1986 Period ............................................................................................................................ 12 III. LOCAL GOVERNANCE IN THE POST 1995 CONSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL REGIME ...... 12 A. Local Governance Under the 1995 Constitution and the Local Governments Act ................................ 12 B. Kampala Capital City: A Unique Position........................................................................................... 14 C. Public Participation in Rule Making in Local Governments and KCCA .............................................. 19 IV. ADJUDICATION OF DISPUTES AND IMPACT OF JUDICIAL REVIEW ................................. 24 D. Adjudication -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 Background Decentralisation reforms are currently ongoing in the majority of developing countries. The nature of decentralisation reforms vary greatly - ranging from mundane technical adjustments of the public administration largely in the form of deconcentration to radical redistribution of political power between central governments and relatively autonomous Local Governments (LGs). Decentralisation reforms hold many promises - including local level democratisation and possibly improved service delivery for the poor. However, effective implementation often lacks behind rhetoric and the effective delivery of promises also depends on a range of preconditions and the country specific context for reforms. In several countries it can be observed that decentralisation reforms are pursued in an uneven manner - some elements of the Government may wish to undertake substantial reforms - other elements will intentionally or unintentionally counter such reforms. Several different forms of decentralisation - foremost elements of devolution, deconcentration and delegation may be undertaken in either a mutually supporting or contradictory manner. Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) recognises that its development assistance at the local level generally and specifically within key sectors that have been decentralised will benefit from a better understanding of the nature of decentralisation in the countries where it works. The present study on local level service delivery, decentralisation and governance in East Africa is undertaken with this in mind. The study is primarily undertaken with a broad analytical objective in mind and is not specifically undertaken as part of a programme formulation although future JICA interventions in East Africa are intended to be informed by the study. 1-2 Objective of the Study The specific objectives of the study are: 1.