Adminstrative Law and Governance Project Kenya, Malawi and Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments Through 2017

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 constituteproject.org Uganda's Constitution of 1995 with Amendments through 2017 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:53 Table of contents Preamble . 14 NATIONAL OBJECTIVES AND DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY . 14 General . 14 I. Implementation of objectives . 14 Political Objectives . 14 II. Democratic principles . 14 III. National unity and stability . 15 IV. National sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity . 15 Protection and Promotion of Fundamental and other Human Rights and Freedoms . 15 V. Fundamental and other human rights and freedoms . 15 VI. Gender balance and fair representation of marginalised groups . 15 VII. Protection of the aged . 16 VIII. Provision of adequate resources for organs of government . 16 IX. The right to development . 16 X. Role of the people in development . 16 XI. Role of the State in development . 16 XII. Balanced and equitable development . 16 XIII. Protection of natural resources . 16 Social and Economic Objectives . 17 XIV. General social and economic objectives . 17 XV. Recognition of role of women in society . 17 XVI. Recognition of the dignity of persons with disabilities . 17 XVII. Recreation and sports . 17 XVIII. Educational objectives . 17 XIX. Protection of the family . 17 XX. Medical services . 17 XXI. Clean and safe water . 17 XXII. Food security and nutrition . 18 XXIII. Natural disasters . 18 Cultural Objectives . 18 XXIV. Cultural objectives . 18 XXV. Preservation of public property and heritage . 18 Accountability . 18 XXVI. Accountability . 18 The Environment . -

Losing Ground.Pdf

The Unprecedented Shrinking of Public Spaces LOSING and Land in Ugandan GROUND? Municipalities A publication of the Cities Alliance Joint Work Programme for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities By Paul. I. Mukwaya, Dmitry Pozhidaev, Denis Tugume, and Peter Kasaija © UNCDF and Cities Alliance 2018 AUTHORS Paul. I. Mukwaya, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Dmitry Pozhidaev, United National Capital Development Fund, Kampala, Uganda Denis Tugume, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Peter Kasaija, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda JWP MANAGEMENT AND COORDINATION Rene Peter Hohmann, Cities Alliance Fredrik Bruhn, Cities Alliance GRAPHIC DESIGN Creatrix Design Group This publication was produced by Cities Alliance and the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) as part of the Cities Alliance Joint Work Programme (JWP) for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities. The U.K. Department for International Development (DFID) chairs the JWP, and its members are the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), UN-Habitat, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), Commonwealth Local Government Forum (CLGF), Ford Foundation, Institute for Housing and Development Studies (IHS) at Erasmus University Rotterdam and the World Bank. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the Cities Alliance, the United Nations, including UNCDF and UNOPS, or the UK Department for International Development (DFID). 2 Losing Ground? SUMMARY There is increasing importance being attached to is to promote economic growth that benefits ALL public spaces and other municipal assets, such as citizens. -

The Development of Law in Uganda*

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 5 | Number 1 Article 2 1983 Autochthony: The evelopmeD nt of Law in Uganda Francis M. Ssekandi Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Ssekandi, Francis M. (1983) "Autochthony: The eD velopment of Law in Uganda," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 5 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol5/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW Volume 5 Number 1 1983 AUTOCHTHONY: THE DEVELOPMENT OF LAW IN UGANDA* FRANCIS M. SSEKANDI** * This is the text of an address delivered at the Law Development Centre in Kampala, Uganda in July 1979, barely three months after the Ugandan Liberation Forces, composed of exiles and led by the Tanzania Defence Forces, booted Idi Amin out of Uganda. An interim government led by Yusufu Lule had assumed office and there was a lively debate in the air on the future of the Ugandan Constitution. Historically, Uganda was ruled by the British as a Protectorate, from 1890 with a measure of internal autonomy for the inhabitants, through a series of "treaties" with the kings of the territories from which Uganda was carved. Thus, on attainment of independence in 1962, the country emerged as a federation of its constituent parts. -

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care in a Long-Term Conflict Setting: Observations from the AIDS Support Organization (TASO) in the Teso Region Emma Smith SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2008 HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care in a Long-Term Conflict Setting: Observations From The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) in the Teso Region Emma Smith SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Recommended Citation Smith, Emma, "HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care in a Long-Term Conflict Setting: Observations From The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) in the Teso Region" (2008). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 99. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/99 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care in a Long-Term Conflict Setting: Observations from The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) in the Teso Region Emma Smith Advisor: Alutia Samuel Academic Directors: Charlotte Mafumbo and Martha Wandera Location: TASO Soroti SIT Uganda Spring 2008 Dedication To all the people living with HIV/AIDS in Teso, who continue to live strongly despite decades of suffering from continuous war, displacement and neglect. May the world come to recognize the struggles that you live with. Acknowledgements There are so many people to whom thanks is owed, it would not be possible to acknowledge them all even if time and space allowed. Primarily, I would like to thank the clients of TASO Soroti, who so willingly welcomed a stranger into their communities and allowed so many questions to be asked of them. -

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: the Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises

Bridging the “Pioneer Gap”: The Role of Accelerators in Launching High-Impact Enterprises A report by the Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs and Village Capital With the support of: Ross Baird Lily Bowles Saurabh Lall The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) The Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) is a global network of organizations that propel entrepreneurship in emerging markets. ANDE members provide critical financial, educational, and busi- ness support services to small and growing businesses (SGBs) based on the conviction that SGBs will create jobs, stimulate long-term economic growth, and produce environmental and social benefits. Ultimately, we believe that SGBS can help lift countries out of poverty. ANDE is part of the Aspen Institute, an educational and policy studies organization. For more information please visit www.aspeninstitute.org/ande. Village Capital Village Capital sources, trains, and invests in impactful seed-stage enter- prises worldwide. Inspired by the “village bank” model in microfinance, Village Capital programs leverage the power of peer support to provide opportunity to entrepreneurs that change the world. Our investment pro- cess democratizes entrepreneurship by putting funding decisions into the hands of entrepreneurs themselves. Since 2009, Village Capital has served over 300 ventures on five continents building disruptive innovations in agriculture, education, energy, environmental sustainability, financial services, and health. For more information, please visit www.vilcap.com. Report released June 2013 Cover photo by TechnoServe Table of Contents Executive Summary I. Introduction II. Background a. Incubators and Accelerators in Traditional Business Sectors b. Incubators and Accelerators in the Impact Investing Sector III. Data and Methodology IV. -

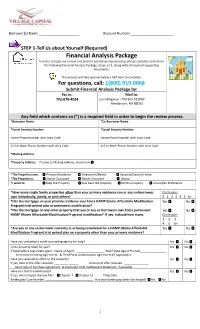

Financial Analysis Package in Order to Begin Our Review and Prevent Any Delays in Processing, Please Complete and Return

Borrower(s) Name Account Number STEP 1-Tell Us about Yourself (Required) Financial Analysis Package In order to begin our review and prevent any delays in processing, please complete and return the following Financial Analysis Package, Steps 1-11, along with all required supporting documents. This process will take approximately a half hour to complete. For questions, call: 1(800) 919-0068 Submit Financial Analysis Package by: Fax to: Mail to: 702-670-4024 Loss Mitigation – PO Box 531667 Henderson, NV 89053 Any field which contains an (*) is a required field in order to begin the review process. *Borrower Name *Co-Borrower Name *Social Security Number *Social Security Number Home Phone Number with Area Code Home Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code Cell or Work Phone Number with Area Code *Mailing Address *Property Address If same as Mailing Address, check here *The Property is my: Primary Residence Investment/Rental Seasonal/Second Home *The Property is: Owner Occupied Renter Occupied Vacant *I want to: Keep the Property Give back the property Sell the property Unsure/No Preference *How many single family properties other than your primary residence you or any co-borrowers Circle one: own individually, jointly, or with others? 0 1 2 3 4 5 6+ *Has the mortgage on your primary residence ever had a HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Yes No Program) trial period plan or permanent modification? *Has the mortgage on any other property that you or any co-borrowers own had a permanent Yes No HAMP (Home Affordable Modification Program) modification? If yes, indicate how many. -

BETTER GROWTH, BETTER CITIES Achieving Uganda’S Development Ambition

BETTER GROWTH, BETTER CITIES Achieving Uganda’s Development Ambition A paper by the Government of Uganda and the New Climate Economy Partnership November 2016 THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA About this paper The analysis in this paper was produced for the New Climate Partnership in Uganda research project, culminating in the report, Achieving Uganda’s Development Ambition: The Economic Impact of Green Growth – An Agenda for Action. This National Urban Transition paper is published as a supporting working paper and provides a fuller elaboration of the urbanisation elements in the broader report. Partners Achieving Uganda’s Development Ambition: The Economic Impact of Green Growth – An Agenda for Action was jointly prepared by the Government of Uganda through the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MFPED), the Ugandan Economic Policy Research Centre (EPRC) Uganda, the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI), the New Climate Economy (NCE), and the Coalition for Urban Transitions (an NCE Special Initiative). Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development Plot 2/12 Apollo Kaggwa Road P.O.Box 8147 Kampala, Uganda +256-414-707000 COALITION FOR URBAN TRANSITIONS A New Climate Economy Special Initiative Acknowledgements The project team members were Russell Bishop, Nick Godfrey, Annie Lefebure, Filippo Rodriguez and Rachel Waddell (NCE); Madina Guloba (EPRC); Maris Wanyera, Albert Musisi and Andrew Masaba (MPFED); and Samson Akankiza, Jahan-zeb Chowdhury, Peter Okubal and John Walugembe (GGGI). The technical -

Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

sustainability Article Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa Jytte Agergaard * , Susanne Kirkegaard and Torben Birch-Thomsen Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 13, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark; [email protected] (S.K.); [email protected] (T.B.-T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In the next twenty years, urban populations in Africa are expected to double, while urban land cover could triple. An often-overlooked dimension of this urban transformation is the growth of small towns and medium-sized cities. In this paper, we explore the ways in which small towns are straddling rural and urban life, and consider how insights into this in-betweenness can contribute to our understanding of Africa’s urban transformation. In particular, we examine the ways in which urbanism is produced and expressed in places where urban living is emerging but the administrative label for such locations is still ‘village’. For this purpose, we draw on case-study material from two small towns in Tanzania, comprising both qualitative and quantitative data, including analyses of photographs and maps collected in 2010–2018. First, we explore the dwindling role of agriculture and the importance of farming, businesses and services for the diversification of livelihoods. However, income diversification varies substantially among population groups, depending on economic and migrant status, gender, and age. Second, we show the ways in which institutions, buildings, and transport infrastructure display the material dimensions of urbanism, and how urbanism is planned and aspired to. Third, we describe how well-established middle-aged households, independent women (some of whom are mothers), and young people, mostly living in single-person households, explain their visions and values of the ways in which urbanism is expressed in small towns. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 Ehealth MONTHLY BULLETIN

WHO UGANDA BULLETIN February 2016 eHEALTH MONTHLY BULLETIN Welcome to this 1st issue of the eHealth Bulletin, a production 2015 of the WHO Country Office. Disease October November December This monthly bulletin is intended to bridge the gap between the Cholera existing weekly and quarterly bulletins; focus on a one or two disease/event that featured prominently in a given month; pro- Typhoid fever mote data utilization and information sharing. Malaria This issue focuses on cholera, typhoid and malaria during the Source: Health Facility Outpatient Monthly Reports, Month of December 2015. Completeness of monthly reporting DHIS2, MoH for December 2015 was above 90% across all the four regions. Typhoid fever Distribution of Typhoid Fever During the month of December 2015, typhoid cases were reported by nearly all districts. Central region reported the highest number, with Kampala, Wakiso, Mubende and Luweero contributing to the bulk of these numbers. In the north, high numbers were reported by Gulu, Arua and Koti- do. Cholera Outbreaks of cholera were also reported by several districts, across the country. 1 Visit our website www.whouganda.org and follow us on World Health Organization, Uganda @WHOUganda WHO UGANDA eHEALTH BULLETIN February 2016 Typhoid District Cholera Kisoro District 12 Fever Kitgum District 4 169 Abim District 43 Koboko District 26 Adjumani District 5 Kole District Agago District 26 85 Kotido District 347 Alebtong District 1 Kumi District 6 502 Amolatar District 58 Kween District 45 Amudat District 11 Kyankwanzi District