Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

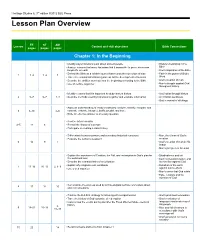

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Contents Illustrations ix Foreword by Alfredo López Austin xvii Acknowledgments xxvii Chapter 1. Converting the Indians in Sixteenth- Century Central Mexico to Christianity 1 Arrival of the Franciscan Missionaries 5 Conversion and the Theory of “Cultural Fatigue” 18 Chapter 2. From Spiritual Conquest to Parish Administration in Colonial Central Mexico 25 Partial Survival of the Ancient Calendar 31 Life in the Indian Parishes of Colonial Central Mexico 32 Chapter 3. A Trilingual, Traditionalist Indigenous Area in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 37 Regional History 40 Three Languages with a Shared Totonac Substratum 48 v Contents Chapter 4. Introduction of Christianity in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 53 Chapter 5. Local Religious Crises in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 63 Andrés Mixcoatl 63 Juan, Cacique of Matlatlán 67 Miguel del Águila, Cacique of Xicotepec 70 Pagan Festivals in Tutotepec 71 Gregorio Juan 74 Chapter 6. The Tutotepec Otomí Rebellion, 1766–1769 81 The Facts 81 Discussion and Interpretation 98 Chapter 7. Contemporary Traditions in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 129 Worship of Tutelary Mountains 130 Shrines and Sacred Constructions 135 Chapter 8. Sacred Drums, Teponaztli, and Idols from the Sierra Norte de Puebla 147 The Huehuetl, or Vertical Drum 147 The Teponaztli, or Female Drum 154 Ancient and Recent Idols in Shrines 173 Chapter 9. Traditional Indigenous Festivities in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 179 The Ancient Festival of San Juan Techachalco at Xicotepec 179 The Annual Festivity of the Tepetzintla Totonacs 185 Memories of Annual Festivities in Other Villages 198 Conclusions 203 Chapter 10. Elements and Accessories of Traditional Native Ceremonies 213 Oblations and Accompanying Rites 213 Prayers, Singing, Music, and Dancing 217 Ritual Idols and Figurines 220 Other Ritual Accessories 225 Chapter 11. -

Religious Studies (RELS) 1

Religious Studies (RELS) 1 RELS 013 Gods, Ghosts, and Monsters RELIGIOUS STUDIES (RELS) This course seeks to be a broad introduction. It introduces students to the diversity of doctrines held and practices performed, and art RELS 002 Religions of the West produced about "the fantastic" from earliest times to the present. The This course surveys the intertwined histories of Judaism, Christianity, fantastic (the uncanny or supernatural) is a fundamental category in and Islam. We will focus on the shared stories which connect these three the scholarly study of religion, art, anthropology, and literature. This traditions, and the ways in which communities distinguished themselves course fill focus both theoretical approaches to studying supernatural in such shared spaces. We will mostly survey literature, but will also beings from a Religious Studies perspective while drawing examples address material culture and ritual practice, to seek answers to the from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, following questions: How do myths emerge? What do stories do? What Central Asian, Native American, and Afro-Caribbean sources from is the relationship between religion and myth-making? What is scripture, earliest examples to the present including mural, image, manuscript, and what is its function in creating religious communities? How do film, codex, and even comic books. It will also introduce students to communities remember and forget the past? Through which lenses and related humanistic categories of study: material and visual culture, with which tools do we define "the West"? theodicy, cosmology, shamanism, transcendentalism, soteriology, For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector eschatology, phantasmagoria, spiritualism, mysticism, theophany, and Taught by: Durmaz the historical power of rumor. -

Shamans and Symbols

SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS PREHISTORY OF SEMIOTICS IN ROCK ART Mihály Hoppál International Society for Shamanistic Research Budapest 2013 Cover picture: Shaman with helping spirits Mohsogollokh khaya, Yakutia (XV–XVIII. A.D. ex: Okladnikov, A. P. 1949. Page numbers in a sun symbol ex: Devlet 1998: 176. Aldan rock site ISBN 978-963-567-054-3 © Mihály Hoppál, 2013 Published by International Society for Shamanistic Research All rights reserved Printed by Robinco (Budapest) Hungary Director: Péter Kecskeméthy CONTENTS List of Figures IX Acknowledgments XIV Preface XV Part I From the Labyrinth of Studies 1. Studies on Rock Art and/or Petroglyphs 1 2. A Short Review of Growing Criticism 28 Part II Shamans, Symbols and Semantics 1. Introduction on the Beginning of Shamanism 39 2. Distinctive Features of Early Shamans (in Siberia) 44 3. Semiotic Method in the Analysis of Rock “Art” 51 4. More on Signs and Symbols of Ancient Time 63 5. How to Mean by Pictures? 68 6. Initiation Rituals in Hunting Communities 78 7. On Shamanic Origin of Healing and Music 82 8. Visual Representations of Cognitive Evolution and Community Rituals 92 Bibliography and Further Readings 99 V To my Dito, Bobo, Dodo and to my grandsons Ákos, Magor, Ábel, Benedek, Marcell VII LIST OF FIGURES Part I I.1.1. Ritual scenes. Sagan Zhaba (Baykal Region, Baykal Region – Okladnikov 1974: a = Tabl. 7; b = Tabl. 16; c = Tabl. 17; d = Tabl. 19. I.1.2. From the “Guide Map” of Petroglyhs and Sites in the Amur Basin. – ex: Okladnikov 1981. No. 12. = Sikachi – Alyan rock site. -

Incense Burner (Incensario) Lid Teotihuacán Central Highlands, Mexico, 150–650 AD Ceramic, Overall: 20 X 17 1/8 X 10 1/4 In

Hirsch Library Research Guide Incense Burner (incensario) Lid Teotihuacán Central Highlands, Mexico, 150–650 AD Ceramic, Overall: 20 x 17 1/8 x 10 1/4 in. (50.8 x 43.5 x 26 cm) Museum purchase funded by Brown Foundation Accessions Endowment Fund Burning incense was central to the religious rituals of most Mesoamerican cultures. It was used in ceremonies of divination, ancestor worship, and veneration of the gods. The smoke also mimicked clouds which brought rain and agricultural abundance. Incense burners from Teotihuacan are among the most elaborate in Mesoamerica. They were used in funerary rites to honor ancestors. The incense burner lid is decorated with a red painted face representing a stone mask. Stone masks were buried with mummy bundles, the wrapped remains of important deceased individuals. The appliquéd decorations include butterflies, flowers, jade jewelry, and seashells, symbolizing the afterlife, war, water, and fertility. The smoke from burning incense escaped through the eyes of the red face and the mouth of the serpent on top. Online Resources: Hirsch Library Online Catalog The Metropolitan Museum of Art Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Articles: (full-text access available on-site; off-site access available through your school library or Houston Public Library) Kubler, George. “The Iconography of the Art of Teotihuacán.” Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology, no. 4 (1967): 1-40. Young-Sánchez, Margaret. “Veneration of the Dead: Religious Ritual on a Pre-Columbian Mirror-Back.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77, no. 9 (1990): 326-351. Ball, Joseph W. and Jennifer T. Taschek. -

![[A Review Of] "Masked Metaphors: Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor in Mesoamerica by John H](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4935/a-review-of-masked-metaphors-masks-of-the-spirit-image-and-metaphor-in-mesoamerica-by-john-h-2404935.webp)

[A Review Of] "Masked Metaphors: Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor in Mesoamerica by John H

Archived version from NCDOCKS Institutional Repository http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/asu/ [A review of] "Masked Metaphors: Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor in Mesoamerica by John H. Markman and Roberta T. Markman" By: Richard M. Carp No Abstract Carp, Richard (1990) "Masked Metaphors: Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor in Mesoamerica by John H. Markman and Roberta T. Markman" - Masked Metaphors: Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor inin Mesoamerica, by Roberta H. Markman and Peter T. MarkmanMarkman c 1990 Richard M. Carp Introduction Masks of the Spirit: Image and Metaphor in Mesoamerica, by Roberta H. Markman and Peter T. Markman is an imposing book. Physically it resembles an art history text, with 250 10 x 13 pages set in double columns of type, 68 black and white plates and 16 color plates. Temporally it spans the period from proto-Olmec cUlture (ca. 1400 BCE) to contemporary folk culture and the work of Mexican artist Ruffino Tamayo. Geographically it covers Mesoamerica, defined as the area from the southern edge of Guatemala to the northern border of Mexico. Conceptually, it is fundamentally interdisciplinary, as the Markmans link religious studies, the history of art and architecture, and theory of art and architecture. The intellectual agenda of the book is threefold: examining the concept, function, role and meaning of mask in Mesoamerica; sympathetically and appreciatively unfolding Mesoamerican religious understanding to a contemporary western aUdience; and demonstrating the persistence of original motifs, beliefs, images and practices throughout Mesoamerica. 1 1 They write that: a painstaking examination of the remaining evidence of spiritual thought • • . -

Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire : Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition / Davíd Carrasco ; with a New Preface.—Rev

Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of Empire Myths and Prophecies in the Aztec Tradition Revised Edition David Carrasco ~University Press of Colorado Copyright © 2000 by the University Press of Colorado International Standard Book Number 0-87081-558-X Published by the University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 Previously published by the University of Chicago Press All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Southern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Carrasco, Davíd. Quetzalcoatl and the irony of empire : myths and prophecies in the Aztec tradition / Davíd Carrasco ; with a new preface.—Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87081-558-X (alk. paper) 1. Aztec mythology. 2. Aztecs—Urban residence. 3. Quetzalcoatl (Aztec deity) 4. Sacred space—Mexico. I. Title. F1219.76.R45.C37 2000 299'.78452—dc21 00-048008 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my mythic figures -

Interpreting Tepantitla Patio 2 Mural (Teotihuacan, Mexico)

INTERPRETING TEPANTITLA PATIO 2 MURAL (TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO) AS AN ANCESTRAL FIGURE ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Art History ____________ by © Atalie Tate Halpin Fall 2018 INTERPRETING TEPANTITLA PATIO 2 MURAL (TEOTIHUACAN, MEXICO) AS AN ANCESTRAL FIGURE A Thesis by Atalie Tate Halpin APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: ______________________________ Sharon Barrios, PhD. APPROVED THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: ______________________________ ______________________________ Asa S. Mittman, PhD., Chair Matthew G. Looper, PhD. Graduate Coordinator ______________________________ Rachel Middleman, PhD. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………….. iv CHAPTER PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 1 II. Tepantitla Patio 2 Mural: Context and Description .......................................................... 4 III. Previous Interpretations: Literature Review …………………………………………… 14 A. “Tlaloc”……………………………………………………………………………... 14 B. “Great Goddess” …………………………………………………………………… 15 C. “Spider Woman” …………………………………………………………………… 18 D. “Water Goddess” and Other Interpretations ……………………………………….. 19 IV. Methods ………………………………………………………………………………... 24 A. Iconography ………………………………………………………………………... 24 B. Cross-cultural and Trans-historical Comparisons …………………………………. 25 V. Iconographic Analysis …………………………………………………………………… 29 A. World Trees and the Cosmic Center ………………………………………………. -

Ancient Zapotec Religion, Like Ancient Mesoamerican Religions in General, Comes Principally from Spanish Colonial Documents (Nicholson 1971:396–97)

Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Preface xvii 1. Introduction 1 2. Zapotec Deities in Sixteenth-Century Documents 13 3. Zapotec Deities in Seventeenth-Century Documents 37 4. Zapotec Temple Priests 75 5. Zapotec Temples: Mitla 107 6. Zapotec Temples: Yagul 167 7. Colaní: Zapotec Community Priests and Their Rituals 215 8. Zapotec Ritual Books and Sacred Calendars 235 9. The Mitla Murals 291 10. Religion in Ancient Zapotec Society 339 References 353 Index 369 1 Introduction This study is about Zapotec religion as it existed around the time of the Spanish Conquest. Our knowledge of ancient Zapotec religion, like ancient Mesoamerican religions in general, comes principally from Spanish colonial documents (Nicholson 1971:396–97). From an analysis of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century docu- ments, the nature of ancient Zapotec religion will be described and interpreted. This description and inter- pretation includes an identification of Zapotec deities, the role of ancestor worship, the nature of the Zapotec cosmos, the composition of the Zapotec priesthood, the rituals and ceremonies performed, and the use of the Zapotec sacred and solar calendars in religious activities. This study also relies on the archaeological record from the Postclassic, the time period leading up to the Spanish Conquest. Archaeological evidence of the nature of Postclassic Zapotec temples, tombs, rit- ual areas of palaces, and representations of deities in murals and artifacts also will be discussed. The role of religion in ancient Zapotec society will be examined in the conclusion to this study. SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND RELIGION To place religion within the context of society and culture requires some definitions.