Chapter Four—Divinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can We Prove God's Existence?

This transcript accompanies the Cambridge in your Classroom video on ‘Can we prove God’s existence?’. For more information about this video, or the series, visit https://www.divinity.cam.ac.uk/study-here/open-days/cambridge-your-classroom Can we prove God’s existence? Professor Catherine Pickstock Faculty of Divinity One argument to prove God’s existence In front of me is an amazing manuscript, is known as the ‘ontological argument’ — called the Proslogion, written nearly 1,000 an argument which, by reason alone – years ago by an Italian Benedictine monk proves that, the very idea of God as a called Anselm. perfect being means that God must exist, that his non-existence would be Anselm went on to become Archbishop of contradictory. Canterbury in 1093, and this manuscript is now kept in the University Library in These kinds of a priori arguments rely on Cambridge. logical deduction, rather than something one has observed or experienced: you It is an exploration of how we can know might be familiar with Kant’s examples: God, written in the form of a prayer, in Latin. Even in translation, it can sound “All bachelors are unmarried men. quite complicated to our modern ears, but Squares have four equal sides. All listen carefully to some of his words here objects occupy space.” translated from Chapters 2 and 3. I am Catherine Pickstock and I teach “If that, than which nothing greater can be Philosophy of Religion at the University of conceived, exists in the understanding Cambridge. And I am interested in how alone, the very being, than which nothing we can know the unknowable, and often greater can be conceived, is one, than look to earlier ways in which thinkers which a greater cannot be conceived. -

New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: a Macroregional Approach

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 24 Number 24 Spring 1991 Article 4 4-1-1991 New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach Gary M. Feinman University of Wisconsin-Madison Linda M. Nicholas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Feinman, Gary M. and Nicholas, Linda M. (1991) "New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 24 : No. 24 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol24/iss24/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Feinman and Nicholas: New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregi NEW PERSPECTIVES ON PREHISPANIC HIGHLAND MESOAMERICA: A MACROREGIONAL APPROACH1 GARY M. FEINMAN LINDA M. NICHOLAS Many social scientists might question the potential role for ar- chaeology in the study of world systems and macroregional politi- cal economies. After all, the principal contributions to this con- temporary research domain have come from history and other social sciences (e.g., Braudel 1972; Wallerstein 1974; Wolf 1982). In addition, most of the world systems literature to date has fo- cused on Europe and other regions of the Old World. This paper takes a somewhat novel tack, one that integrates contemporary findings in archaeology and history to expand and contribute to current debates concerning the nature of ancient world systems and interregional relations. Yet, the geographic focus is not Rome or Greece or even the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, but rather prehispanic Mesoamerica, an area that encom- passes the southern two-thirds of what is now Mexico, as well as Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. -

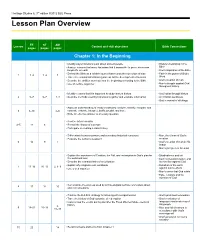

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Cerro Danush: an Exploration of the Late Classic Transition in the Tlacolula Valley, Oaxaca

FAMSI © 2008: Ronald Faulseit Cerro Danush: An Exploration of the Late Classic Transition in the Tlacolula Valley, Oaxaca. Research Year: 2007 Culture: Zapotec Chronology: Late Classic Location: Oaxaca Valley, México Site: Dainzú-Macuilxóchitl Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Notes on Dating and Ceramic Phases for the Valley of Oaxaca Project Goals and Theoretical Approach Field Operations 2007 – 2008 Introduction Site Mapping Procedures Discussion of Features Mapped on Cerro Danush Rock Paintings Natural Springs Caves Man-Made Terraces Surface Collection Procedures Artifact Analysis Procedures 1 Initial Conclusions and Interpretations Cerro Danush in the Late Postclassic Period, A.D. 1200-1521 Cerro Danush: Ritual Landscape and the Festival of the Cross Cerro Danush in the Early Postclassic Period, A.D. 900 – 1200 The Oaxaca Valley in the Late Classic Period, A.D. 500 – 900 Dainzú-Macuilxóchitl in the Late Classic Period, A.D. 500 – 900 Dainzú-Macuilxóchitl as a District Center List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract This report describes and provides preliminary interpretations for the 2007-2008 field season of mapping and surface collection conducted on Cerro Danush at the site of Dainzú-Macuilxóchitl in Oaxaca, Mexico. Dainzú-Macuilxóchitl is an expansive settlement that was an important part of the Prehispanic Zapotec tradition. Over 130 man-made terraces were mapped, all dating to the Late Classic period (500-900 A.D.), and a large terrace complex found at the summit of Cerro Danush is interpreted as the civic-ceremonial center of the site during that time. I argue that the Late Classic shift in civic-ceremonial focus away from Cerro Dainzú to Cerro Danush implies direct involvement at the site from the nearby urban center of Monte Albán. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 6 Number 1

Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Spring 2015 Article 1 2015 IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal Recommended Citation "IMW Journal of Religious Studies Volume 6 Number 1." Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 6, no. 1 (2015). https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/imwjournal/vol6/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies is designed to promote the academic study of religion at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The journal is a student initiative affiliated with the Religious Studies Program and the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Utah State University. Our academic review board includes professional scholars specializing in Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Mormonism, as well as specialists in the fields of History, Philosophy, Psychology, Anthropology, Sociology, and Religion. The journal is housed in the Intermountain West, but gladly accepts submissions from students throughout the United States and around the world. INTERMOUNTAIN WEST JOURNAL Of RELIGIOUS STUDIES ‡ Advisors PHILIP BARLOW RAVI GUPTA Managing Editor CORY M. NANI Editor JEDD COX Associate Editor CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS Emeritus Editors CHRISTOPHER BLYTHE MARK BULLEN RASMUSON DAVID MUNK Cover Design CORY M. NANI ________________________________________________________________ Academic Review Board RAVI GUPTA Utah State University REID L. NIELSON LDS Church Historical Department KAREN RUFFLE University of Toronto ANNE-MARIE CUSAC Roosevelt University STEPHEN TAYSOM Cleveland State University KECIA ALI Boston University PETER VON SIVERS University of Utah R. -

Early Mesoamerican Civilizations

2 Early Mesoamerican Civilizations MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES CULTURAL INTERACTION The Later American civilizations • Mesoamerica • Zapotec Olmec created the Americas’ relied on the technology and • Olmec • Monte first civilization, which in turn achievements of earlier cultures Albán influenced later civilizations. to make advances. SETTING THE STAGE The story of developed civilizations in the Americas begins in a region called Mesoamerica. (See map on opposite page.) This area stretches south from central Mexico to northern Honduras. It was here, more than 3,000 years ago, that the first complex societies in the Americas arose. TAKING NOTES The Olmec Comparing Use a Mesoamerica’s first known civilization builders were a people known as the Venn diagram to compare Olmec and Olmec. They began carving out a society around 1200 B.C. in the jungles of south- Zapotec cultures. ern Mexico. The Olmec influenced neighboring groups, as well as the later civi- lizations of the region. They often are called Mesoamerica’s “mother culture.” The Rise of Olmec Civilization Around 1860, a worker clearing a field in the Olmec hot coastal plain of southeastern Mexico uncovered an extraordinary stone sculp- both ture. It stood five feet tall and weighed an estimated eight tons. The sculpture Zapotec was of an enormous head, wearing a headpiece. (See History Through Art, pages 244–245.) The head was carved in a strikingly realistic style, with thick lips, a flat nose, and large oval eyes. Archaeologists had never seen anything like it in the Americas. This head, along with others that were discovered later, was a remnant of the Olmec civilization. -

The Carved Human Femprs from Tomb 1, Chiapa De Corzo, Chiapas, Mexico

PAPERS of the NEW WOR LD ARCHAEOLO G ICAL FOUNDATION NUMBER SIX THE CARVED HUMAN FEMPRS FROM TOMB 1, CHIAPA DE CORZO, CHIAPAS, MEXICO by PIERRE AGRINIER PUBLICATION No. 5 NEW WORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION ORINDA, CALIFORNIA 1960 NEW WORLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION 1960 OFFICERS THOMAS STUART FERGUSON, President 1 Irving Lane, Orinda, California ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D., First Vice-President MILTON R. HUNTER, PH.D., Vice-President ScoTT H. DUNHAM, Secretary-Treasurer J. ALDEN MASON, PH.D., Editor and Field Advisor GARETH W. LowE, Field Director, 1956-1959 FREDRICK A. PETERSON, Field Director, 1959-1960 DIRECTORS ADVISORY COMMITTEE SCOTT H. DUNHAM, C.P.A. PEDRO ARMILLAS, PH.D. THOMAS STUART FERGUSON, ESQ. GORDON F. EKHOLM, PH.D. M. WELLS JAKEMAN, PH.D. J. POULSON HUNTER, M.D. ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D. MILTON R. HUNTER, PH.D. ALFRED V. KIDDER, PH.D. EDITORIAL OFFICE NICHOLAS G. MORGAN, SR. ALDEN MASON LE GRAND RICHARDS J. UNIVERSITY MUSEUM ERNEST A. STRONG UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Philadelphia 4, Pa. J. ALDEN MASON EDITOR Orders for and correspondence regarding the publications of The New World Archaeological Foundation should be sent to SCOTT H. DUNHAM, Secretary 510 Crocker Building San Francisco 4, California Price $2.00 Printed by THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER Philadelphia 4, Pa. PAPERS of the NEW WOR LD ARCHAEOLO G ICAL FOUNDATION NUMBER SIX THE CARVED HUMAN FEMURS FROM TOMB 1, CHIAP A DE CORZO, CHIAPAS, MEXICO by PIERRE AGRINIER PUB LICATION No. 5 NEW WoRLD ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION ORINDA, CALIFORNIA 1960 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 I. DESCRIPTION ..•...........•......................•... 2 Bone 1 .................................... 2 Bone 2 2 Bone 3 2 Bone 4 3 Technique ................................................ -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Pre-Columbian Agriculture in Mexico Carol J

Pre-Columbian Agriculture in Mexico Carol J. Lange, SCSC 621, International Agricultural Research Centers- Mexico, Study Abroad, Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Texas A&M University Introduction The term pre-Columbian refers to the cultures of the Americas in the time before significant European influence. While technically referring to the era before Christopher Columbus, in practice the term usually includes indigenous cultures as they continued to develop until they were conquered or significantly influenced by Europeans, even if this happened decades or even centuries after Columbus first landed in 1492. Pre-Columbian is used especially often in discussions of the great indigenous civilizations of the Americas, such as those of Mesoamerica. Pre-Columbian civilizations independently established during this era are characterized by hallmarks which included permanent or urban settlements, agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies. Many of these civilizations had long ceased to function by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late fifteenth-early sixteenth centuries), and are known only through archaeological evidence. Others were contemporary with this period, and are also known from historical accounts of the time. A few, such as the Maya, had their own written records. However, most Europeans of the time largely viewed such text as heretical and few survived Christian pyres. Only a few hidden documents remain today, leaving us a mere glimpse of ancient culture and knowledge. Agricultural Development Early inhabitants of the Americas developed agriculture, breeding maize (corn) from ears 2-5 cm in length to perhaps 10-15 cm in length. Potatoes, tomatoes, pumpkins, and avocados were among other plants grown by natives. -

Once Again, Nationality and Religion

genealogy Article Once Again, Nationality and Religion Steven E. Grosby Department of Philosophy and Religion, Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29634, USA; [email protected] Received: 22 July 2019; Accepted: 5 September 2019; Published: 8 September 2019 Abstract: An examination of the relation between nationality and religion calls for comparative analysis. There is a variability of the relation over time and from one nation and religion to another. At times, nationality and religion have clearly converged; but there have also been times when they have diverged. Examination of this variability may lead to generalizations that can be achieved through comparison. While the generalizations achieved through a comparative analysis of the relation are heuristically useful, there are complications that qualify those generalizations. Moreover, while further refining the comparative framework of the relation between nationality and religion remains important, it is not the pressing theoretical problem. That problem is ascertaining what is distinctive of religion as a category of human thought and action such that it is distinguishable from nationality and, thus, a variable in the comparative analysis. It may be that determining that distinctiveness results in the need for a different framework to analyze the relation between nationality and religion. Keywords: axial age; kinship; monolatry; monotheism; nation; priest; religion; territory 1. Introduction Examination of the relation between nationality and religion calls for comparative analysis. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tv1p1rr Author Flores-Marcial, Xochitl Marina Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 © Copyright by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A History of Guelaguetza in Zapotec Communities of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, 16th Century to the Present by Xóchitl Marina Flores-Marcial Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Kevin B. Terraciano, Chair My project traces the evolution of the Zapotec cultural practice of guelaguetza, an indigenous sharing system of collaboration and exchange in Mexico, from pre-Columbian and colonial times to the present. Ironically, the term "guelaguetza" was appropriated by the Mexican government in the twentieth century to promote an annual dance festival in the city of Oaxaca that has little to do with the actual meaning of the indigenous tradition. My analysis of Zapotec-language alphabetic sources from the Central Valley of Oaxaca, written from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, reveals that Zapotecs actively participated in the sharing system during this long period of transformation. My project demonstrates that the Zapotec sharing economy functioned to build and reinforce social networks among households in Zapotec communities.