Interpreting Tepantitla Patio 2 Mural (Teotihuacan, Mexico)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

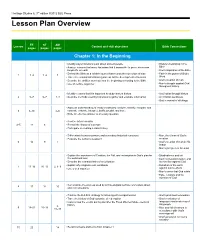

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

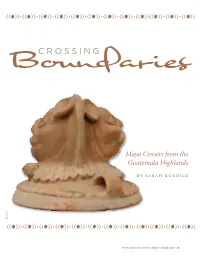

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

The Economic Organization of the Teotihuacan Priesthood: Hypotheses and Considerations 321

.A.RT, IDEOLOGY, AND THE CITY OF TEOTIHUACAN A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks 8TH AND 9TH OCTOBER 1988 Janet Catherine Berlo, Editor Durnbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. Copyright © 1992 by Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Art, ideology, and the city ofTeotihuacan: a symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 8th and 9th October 1988 I Janet Catherine Berlo, editor. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN o-88402-205-6 r. Teotihuacin Site (SanJuan Teotihuacin, Mexico)-Congresses. 2. Indians of Mexico-Mexico-San Juan Teotihuacan-Art-Congresses. J. Indians ofMexico-Mexico-SanJuan Teotihuacan-Religion and mythology-Congresses. 4· SanJuan Teotihuacan (Mexico) Antiquities-Congresses. 5· Mexico-Antiquities-Congresses. I. Berlo, Janet Catherine. II. Dumbarton Oaks. FI2I9. I. T27A73 1993 972'. 52-de2o 92-8244 Contents FOREWORD Vll t { PREFACE XI ;I SUSAN T. EVANS AND JANET CATHERINE BERLO Teotihuacan: An Introduction I Ili ! MARTHA L. SEMPOWSKI Economic and Social Implications of Variations in Mortuary Practices at Teotihuacan MICHAEL W. SPENCE Tlailotlacan, a Zapotec Enclave in Teotihuacan 59 MARGARET H. TURNER Style in Lapidary Technology: Identifying the Teotihuacan Lapidary Industry RUBEN CABRERA CASTRO A Survey of Recently Excavated Murals at Teotihuacan II3 JANET CATHERINE BERLO Icons and Ideologies at Teotihuacan: The Great Goddess "'! Reconsidered 129 KARL A. TAUBE The Iconography of Mirrors at Teotihuacan I v Contents SABURO SUGIYAMA Rulership, Warfare, and Human Sacrifice at the Ciudadela: An Iconographic Study of Feathered Serpent Representations 20 5 GEORGE L. COWGILL Teotihuacan Glyphs and Imagery in the Light of Some Early Colonial Texts 231 JAMES C. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

Oral Tradition 25.2

Oral Tradition, 25/2 (2010): 325-363 “Secret Language” in Oral and Graphic Form: Religious-Magic Discourse in Aztec Speeches and Manuscripts Katarzyna Mikulska Dąbrowska Introduction On the eve of the conquest, oral communication dominated Mesoamerican society, with systems similar to those defined by Walter Ong (1992 [1982]), Paul Zumthor (1983), and Albert Lord (1960 [2000]), although a written form did exist. Its limitations were partly due to the fact that it was used only by a limited group of people (Craveri 2004:29), and because the Mixtec and Nahua systems do not totally conform to a linear writing system.1 These forms of graphic communication are presented in pictographic manuscripts, commonly known as codices. The analysis of these sources represents an almost independent discipline, as they increasingly become an ever more important source for Mesoamerican history, religion, and anthropology. The methodology used to study them largely depends on how the scholar defines “writing.” Some apply the most rigid definition of a system based on the spoken language and reflecting its forms and/or structures (e.g., Coulmas 1996:xxvi), while others accept a broader definition of semasiographic systems that can transmit ideas independent of actual spoken language (yet function at the same logical level) and thus also constitute writing (e.g., Sampson 1985:26-31). The aim of this study is to analyze the linguistic “magical-religious” register of the Nahua people, designated as such because it was used for communication with the sacred realm. In this respect, it represents one of the “sacred languages,” as classified by Zumthor (1983:53). -

Codex Nicholson Pp. 59-126

Codex Nicholson 59 THE GREAT NITPICKER Davíd Carrasco I met H. B. Nicholson for the first time in 1974 at a session on Magic Books of Mexico at the 41st Internacional Congreso de Americanistas in Mexico City. He and the great Wigberto Jiménez Moreno were chairing the session, and I was thrilled to be in the audience and listen to these two wonderful scholars. Afterward I walked up and introduced myself to Professor Nicholson and told him I was planning to write a dissertation on Quetzalcoatl while completing my Ph.D. at the University of Chicago. We spoke for a few minutes as he was clearly interested in talking about Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl. He wondered if I’d read his dissertation. When I said I had come to know about it through reading Alfredo López Austin’s (1973) book, Hombre-Díos, but had not been able to obtain a copy, he promised to send me one. Soon after returning to Colorado I wrote him to thank him for our exchange and inquired about his Harvard dissertation. To my surprise and delight, a photocopy of his 1957 dissertation, Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl of Tollan: a Problem in Mesoamerican Ethnohistory, arrived at my home. As a student of religion struggling to make my way through the primary sources, a great feeling of relief came over me: I’ve just been saved! Reading through Nicholson’s dissertation focused my mind and work. The clarity, the pinpoint research, the overall organization, and the reconstruction of the “tale” all read like a tour de force legal argument making the case that the Aztecs had inherited and internalized a sacred history about the Toltec priest-king that shaped their priestly practices, religious world view and, later, their interpretation of the encounter with the Spaniards.