Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A

La Corona Notes 1(1) The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A. Canuto Middle American Research Institute / Tulane University Tomás Barrientos Q. Universidad del Valle de Guatemala In 2008, the Proyecto Regional Arqueológico monuments led to the realization that these texts La Corona (PRALC; directed by Marcello A. contained several terms not only common in, but Canuto and Tomás Barrientos Q.) was established also unique to the texts of Site Q (Stuart 2001). to coordinate archaeological research in the The locative term thought to be the ancient Maya northwestern sector of the Guatemalan Peten. name of Site Q (sak nikte’), the name of a Site Q ruler Centered at the site of La Corona (N17.52 W90.38), (Chak Ak’aach Yuk), titles characteristic of Site Q PRALC initiated the first long-term scientific rulers (sak wayis), and references to Site Q’s most research of both the site and the surrounding important ally (Kaanal), were all present in the region. To a large extent, however, La Corona texts found at La Corona. Despite expressed doubts was well known long before PRALC began its regarding the identification of La Corona as Site Q investigations, since it was ultimately revealed to (Graham 2002), petrographic similarities between be the mysterious “Site Q.” As the origin of over stone samples from a Site Q monument and from two dozen hieroglyphic panels looted in the 1960s exemplars collected at the site of La Corona led and attributed to the as-yet-unidentified “Site Q” Stuart (2001) to suggest that La Corona was Site Q. -

Magic and the Supernatural

Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Magic and the Supernatural At the Interface Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E An At the Interface research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/at-the-interface/ The Evil Hub ‘Magic and the Supernatural’ 2012 Magic and the Supernatural Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-095-5 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table of Contents Preface vii Scott Hendrix PART 1 Philosophy, Religion and Magic Magic and Practical Agency 3 Brian Feltham Art, Love and Magic in Marsilio Ficino’s De Amore 9 Juan Pablo Maggioti The Jinn: An Equivalent to Evil in 20th Century 15 Arabian Nights and Days Orchida Ismail and Lamya Ramadan PART 2 Magic and History Rational Astrology and Empiricism, From Pico to Galileo 23 Scott E. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

The Supernatural Is What the Paranormal May Be: Real

66 http://onfaith.washingtonpost.com/onfaith/panelists/willis_e_elliott/2008/07/the_supernatural_is_what_the_p.html The Supernatural Is What the Paranormal May Be: Real “Please leave,” said Mircea Eliade (editor-in-chief of the 17-volume “Encyclopedia of Religion”). With a question, he had just begun a lecture to a group of liberal clergy at the University of Chicago. His question: “Do you think that the sacred tree in the center of the clearing is not holy? If so, please raise your hand.” To the hand-raisers – about a third of us – he said, “Please leave.” The room became dead quiet; nobody left. Minds not open to the supernaturalseemed to him subhuman: openness to experiencing the transcendent, the beyond, is a constitutive characteristic of human consciousness. The great phenomenologist was talking about the supernatural, not the paranormal. The current “On Faith” question asks about the two: “Polls routinely show that 75% of Americans hold some form of belief in the paranormal such as astrology, telepathy and ghosts. All religions contain beliefs in the supernatural. Is there a link? What’s the difference?” 1.....The difference appears in the delightful, uproarious film, “The Gods Must Be Crazy.” Out of the open cockpit of a small biplane, somebody throws an empty coke bottle, which lands in a small village of near-naked primitives, overwhelming them with fear of the unknown and befuddling them with cognitive dissonance. We viewers know that the event was natural, almost normal. But to the primitives, the event was para-normal, preter- natural, beyond both expectation and explanation. What to do? The leader rose and supernaturalized the event. -

Occult Feelings: Esotericism and Queer Relationality in The

OCCULT FEELINGS: ESOTERICISM AND QUEER RELATIONALITY IN THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Brant Michael Torres January 2014 © 2014 Brant Michael Torres ii Brant Michael Torres, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Occult Feelings: Esotericism and Queer Relationality in Nineteenth-Century US Literature uncovers the esoteric investments central to American Transcendentalism to analyze how authors used the occult to explore new, and often erotic, relational possibilities. I reveal the different ways that authors, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott, employed the occult to reimagine intimacy. To this end, my project studies literary representations of occult practices like alchemy and spirit contact, as well as the esoteric philosophies of writers like Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme that fascinated authors in the nineteenth-century. Authors of American Transcendentalism—with their depictions of an esoteric correspondence between embodied and disembodied subjects, celestial bodies, plants, and inanimate objects— envisioned relationality as hidden, mystical, and non-dyadic. As such, the occult became a way to find more open and dynamic modes of relation beyond direct interpersonal contact. For example, reading alchemy in Hawthorne, I reveal how an obsessive interest in creating and then suspending homoerotic intimacies allows for queer modes of relation. In Fuller, I illustrate how her mystic intimacy with flowers highlights affective connections while insisting on an ever-present distance with objects. For Bronson Alcott, I demonstrate how his esoteric investments transform his relation to divinity. -

Kahk' Uti' Chan Yopat

Glyph Dwellers Report 57 September 2017 A New Teotiwa Lord of the South: K’ahk’ Uti’ Chan Yopat (578-628 C.E.) and the Renaissance of Copan Péter Bíró Independent Scholar Classic Maya inscriptions recorded political discourse commissioned by title-holding elite, typically rulers of a given city. The subject of the inscriptions was manifold, but most of them described various period- ending ceremonies connected to the passage of time. Within this general framework, statements contained information about the most culturally significant life-events of their commissioners. This information was organized according to discursive norms involving the application of literary devices such as parallel structures, difrasismos, ellipsis, etc. Each center had its own variations and preferences in applying such norms, which changed during the six centuries of Classic Maya civilization. Epigraphers have thus far rarely investigated Classic Maya political discourse in general and its regional-, site-, and period-specific features in particular. It is possible to posit very general variations, for example the presence or absence of secondary elite inscriptions, which makes the Western Maya region different from other areas of the Maya Lowlands (Bíró 2011). There are many other discursive differences not yet thoroughly investigated. It is still debated whether these regional (and according to some) temporal discursive differences related to social phenomena or whether they strictly express literary variation (see Zender 2004). The resolution of this question has several implications for historical solutions such as the collapse of Classic Maya civilization or the hypothesis of status rivalry, war, and the role of the secondary elite. There are indications of ruler-specific textual strategies when inscriptions are relatively uniform; that is, they contain the same information, and their organization is similar. -

LA 119 Maymester Seminar Guatemala and Belize Dr. David

LA 119 Maymester Seminar Guatemala And Belize Dr. David Stuart, Department of Art and Art History Dr. Stuart’s Office Office Hours email ART 1.412B (Mesoamerica Center) T 1:00-2:30 PM [email protected] Class Times: Tuesdays 2:30 PM - 4:30 PM in ART 2.208 Class meets eight times on the Following dates: January 29, February 12, February 26, March 12, March 26, April 9, April 23, and May 7 Topic Description: Maya civilization emerged on the scene over 3,000 years ago within what is today southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. The Maya soon developed one of the great civilizations of the ancient world, well known for its impressive ruins, temple pyramids and palaces, stone sculptures, and elaborate hieroglyphic writing system. The Maya experienced profound changes and disruptions throughout their history and development, including the so-called “collapse” of many cities around 800-900 AD. The arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century and the British in the 18th century then brought near destruction to their world, but Maya peoples emerged resilient in the wake of conquest in what are now the modern nations of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Today six million strong, the modern Maya continue to express their cultural identity in the art and politics of modern Mexico and Central America. Their cultural legacy has left its mark on northern Central America in many ways, and the tortured indigenous history of the region continues to shape the politics of our own time. Course Objectives: This class prepares students on the history of the Maya of Guatemala and Belize, spanning the Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and modern times, and provides the literature and visual culture background for the Maymester study abroad course on Maya Art and Architecture (ARH 347M) taking place in Guatemala and Belize. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

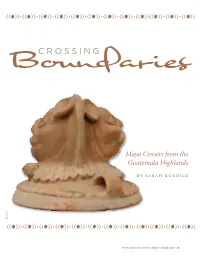

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’S Gardens Of

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’s Gardens of the Moon Emil Wallner ENGK01 Bachelor’s thesis in English Literature Spring semester 2014 Center for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Ellen Turner Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 The Collective Unconscious and the Archetype of Rebirth.................................................2 Renovatio (Renewal) – Kellanved and Dancer, and K’rul...................................................6 Resurrection – Rigga, Hairlock, Paran, and Tattersail.........................................................9 Metempsychosis – Tattersail and Silverfox.......................................................................15 The Presence of the Rebirth Archetype and Its Consequences..........................................17 Conclusion..........................................................................................................................22 Works Cited........................................................................................................................24 Introduction Rebirth is a phenomenon present in a number of religions and myths all around the world. The miraculous resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the perennial process of reincarnation in Hinduism, are just two examples of preternatural rebirths many people believe in today. However, rebirth does not need to be a paranormal process where someone -

The New Age Embraces Shamanism

CHRISTIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE P.O. Box 8500, Charlotte, NC 28271 Article: DS836 THE NEW AGE EMBRACES SHAMANISM This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 25, number 4 (2003) as a companion to the feature article Shamanism: Eden or Evil? by Mark Andrew Ritchie. For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org A few decades ago, “shamanism” was a word known mainly by anthropologists. As the New Age movement grew in the West, however, many others were introduced to and embraced spiritual practices drawn from several primitive cultures such as Native American, various Latin American, Hawaiian, Eskimo, and other indigenous groups. These practices, which emphasized trance and ecstatic states, spirit contact, animal spirits, out-of-body experiences, and nontraditional healing1 were harmonious with the budding New Age beliefs that emphasized the earth, transcendence through drugs, and multileveled realities. Neoshamanism thus was born. Two of the most influential people in the rise of neoshamanism were Carlos Castaneda and Lynn Andrews, who claimed to have been initiated into shamanism by native teachers. Castaneda claimed to have been a student of Yaqui Indian Don Juan Matus, while Lynn Andrews claimed to have studied under women teachers such as Agnes Whistling Elk and Ruby Plenty Chiefs. Castaneda’s many books on shamanism, including his influential and controversial The Teachings of Don Juan published in 1968, as well as Andrews’s many books since 1981, have sold quite well. Castaneda, an anthropology student in 1960 who set out to research the medicinal properties of plants, enlisted the help of shaman-sorcerer Don Juan.2 Thus began Castaneda’s journey into the world of sorcery, where dreams and visions became the prime reality — a spiritual trip that included hallucinogens, which was one of the touchstones of “spiritual awakening” in the 1960s and 1970s.