Celina Jeffery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magic and the Supernatural

Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Magic and the Supernatural At the Interface Series Editors Dr Robert Fisher Dr Daniel Riha Advisory Board Dr Alejandro Cervantes-Carson Dr Peter Mario Kreuter Professor Margaret Chatterjee Martin McGoldrick Dr Wayne Cristaudo Revd Stephen Morris Mira Crouch Professor John Parry Dr Phil Fitzsimmons Paul Reynolds Professor Asa Kasher Professor Peter Twohig Owen Kelly Professor S Ram Vemuri Revd Dr Kenneth Wilson, O.B.E An At the Interface research and publications project. http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/at-the-interface/ The Evil Hub ‘Magic and the Supernatural’ 2012 Magic and the Supernatural Edited by Scott E. Hendrix and Timothy J. Shannon Inter-Disciplinary Press Oxford, United Kingdom © Inter-Disciplinary Press 2012 http://www.inter-disciplinary.net/publishing/id-press/ The Inter-Disciplinary Press is part of Inter-Disciplinary.Net – a global network for research and publishing. The Inter-Disciplinary Press aims to promote and encourage the kind of work which is collaborative, innovative, imaginative, and which provides an exemplar for inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of Inter-Disciplinary Press. Inter-Disciplinary Press, Priory House, 149B Wroslyn Road, Freeland, Oxfordshire. OX29 8HR, United Kingdom. +44 (0)1993 882087 ISBN: 978-1-84888-095-5 First published in the United Kingdom in eBook format in 2012. First Edition. Table of Contents Preface vii Scott Hendrix PART 1 Philosophy, Religion and Magic Magic and Practical Agency 3 Brian Feltham Art, Love and Magic in Marsilio Ficino’s De Amore 9 Juan Pablo Maggioti The Jinn: An Equivalent to Evil in 20th Century 15 Arabian Nights and Days Orchida Ismail and Lamya Ramadan PART 2 Magic and History Rational Astrology and Empiricism, From Pico to Galileo 23 Scott E. -

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008

Drone Records Mailorder-Newsflash MARCH / APRIL 2008 Dear Droners & Lovers of thee UN-LIMITED music! Here are our new mailorder-entries for March & April 2008, the second "Newsflash" this year! So many exciting new items, for example mentioning only the great MUZYKA VOLN drone-compilation of russian artists, the amazing 4xLP COIL box, a new LP by our beloved obscure-philosophist KALLABRIS, deep meditation-drones by finlands finest HALO MANASH, finally some new releases by URE THRALL, and the four new Drone EPs on our own label are now out too!! Usually you find in our listing URLs of labels or artists where its often possible to listen to extracts of the releases online. LABEL-NEWS: We are happy to take pre-orders for: OÖPHOI - Potala 10" VINYL Substantia Innominata SUB-07 Two long tracks of transcendental drones by the italian deep-ambient master, the first EVER OÖPHOI-vinyl!! "Dedicated to His Holiness The Dalai Lama and to Tibet's struggle for freedom." Out in a few weeks! Soon after that we have big plans for the 10"-series with releases by OLHON ("Lucifugus"), HUM ("The Spectral Ship"), and VOICE OF EYE, so watch out!!! As always, pre-orders & reservations are possible. You also may ask for any new release from the more "experimental" world that is not listed here, we are probably able to get it for you. About 80% of the titles listed are in stock, others are backorderable quickly. The FULL mailorder-backprogramme is viewable (with search- & orderfunction) on our website www.dronerecords.de. Please send your orders & all communication to: [email protected] PLEASE always mention all prices to make our work on your orders easier & faster and to avoid delays, thanks a lot ! (most of the brandnew titles here are not yet listed in our database on the website, but will be soon, so best to order from this list in reply) BUILD DREAMACHINES THAT HELP US TO WAKE UP! with best drones & dark blessings from BarakaH 1 AARDVARK - Born CD-R Final Muzik FMSS06 2007 lim. -

The Supernatural Is What the Paranormal May Be: Real

66 http://onfaith.washingtonpost.com/onfaith/panelists/willis_e_elliott/2008/07/the_supernatural_is_what_the_p.html The Supernatural Is What the Paranormal May Be: Real “Please leave,” said Mircea Eliade (editor-in-chief of the 17-volume “Encyclopedia of Religion”). With a question, he had just begun a lecture to a group of liberal clergy at the University of Chicago. His question: “Do you think that the sacred tree in the center of the clearing is not holy? If so, please raise your hand.” To the hand-raisers – about a third of us – he said, “Please leave.” The room became dead quiet; nobody left. Minds not open to the supernaturalseemed to him subhuman: openness to experiencing the transcendent, the beyond, is a constitutive characteristic of human consciousness. The great phenomenologist was talking about the supernatural, not the paranormal. The current “On Faith” question asks about the two: “Polls routinely show that 75% of Americans hold some form of belief in the paranormal such as astrology, telepathy and ghosts. All religions contain beliefs in the supernatural. Is there a link? What’s the difference?” 1.....The difference appears in the delightful, uproarious film, “The Gods Must Be Crazy.” Out of the open cockpit of a small biplane, somebody throws an empty coke bottle, which lands in a small village of near-naked primitives, overwhelming them with fear of the unknown and befuddling them with cognitive dissonance. We viewers know that the event was natural, almost normal. But to the primitives, the event was para-normal, preter- natural, beyond both expectation and explanation. What to do? The leader rose and supernaturalized the event. -

Occult Feelings: Esotericism and Queer Relationality in The

OCCULT FEELINGS: ESOTERICISM AND QUEER RELATIONALITY IN THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY UNITED STATES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Brant Michael Torres January 2014 © 2014 Brant Michael Torres ii Brant Michael Torres, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Occult Feelings: Esotericism and Queer Relationality in Nineteenth-Century US Literature uncovers the esoteric investments central to American Transcendentalism to analyze how authors used the occult to explore new, and often erotic, relational possibilities. I reveal the different ways that authors, such as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott, employed the occult to reimagine intimacy. To this end, my project studies literary representations of occult practices like alchemy and spirit contact, as well as the esoteric philosophies of writers like Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme that fascinated authors in the nineteenth-century. Authors of American Transcendentalism—with their depictions of an esoteric correspondence between embodied and disembodied subjects, celestial bodies, plants, and inanimate objects— envisioned relationality as hidden, mystical, and non-dyadic. As such, the occult became a way to find more open and dynamic modes of relation beyond direct interpersonal contact. For example, reading alchemy in Hawthorne, I reveal how an obsessive interest in creating and then suspending homoerotic intimacies allows for queer modes of relation. In Fuller, I illustrate how her mystic intimacy with flowers highlights affective connections while insisting on an ever-present distance with objects. For Bronson Alcott, I demonstrate how his esoteric investments transform his relation to divinity. -

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’S Gardens Of

The Presence of the Jungian Archetype of Rebirth in Steven Erikson’s Gardens of the Moon Emil Wallner ENGK01 Bachelor’s thesis in English Literature Spring semester 2014 Center for Languages and Literature Lund University Supervisor: Ellen Turner Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 The Collective Unconscious and the Archetype of Rebirth.................................................2 Renovatio (Renewal) – Kellanved and Dancer, and K’rul...................................................6 Resurrection – Rigga, Hairlock, Paran, and Tattersail.........................................................9 Metempsychosis – Tattersail and Silverfox.......................................................................15 The Presence of the Rebirth Archetype and Its Consequences..........................................17 Conclusion..........................................................................................................................22 Works Cited........................................................................................................................24 Introduction Rebirth is a phenomenon present in a number of religions and myths all around the world. The miraculous resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the perennial process of reincarnation in Hinduism, are just two examples of preternatural rebirths many people believe in today. However, rebirth does not need to be a paranormal process where someone -

Catalog INTERNATIONAL

اﻟﻤﺆﺗﻤﺮ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻲ اﻟﻌﺸﺮون ﻟﺪﻋﻢ اﻻﺑﺘﻜﺎر ﻓﻲ ﻣﺠﺎل اﻟﻔﻨﻮن واﻟﺘﻜﻨﻮﻟﻮﺟﻴﺎ The 20th International Symposium on Electronic Art Ras al-Khaimah 25.7833° North 55.9500° East Umm al-Quwain 25.9864° North 55.9400° East Ajman 25.4167° North 55.5000° East Sharjah 25.4333 ° North 55.3833 ° East Fujairah 25.2667° North 56.3333° East Dubai 24.9500° North 55.3333° East Abu Dhabi 24.4667° North 54.3667° East SE ISEA2014 Catalog INTERNATIONAL Under the Patronage of H.E. Sheikha Lubna Bint Khalid Al Qasimi Minister of International Cooperation and Development, President of Zayed University 30 October — 8 November, 2014 SE INTERNATIONAL ISEA2014, where Art, Science, and Technology Come Together vi Richard Wheeler - Dubai On land and in the sea, our forefathers lived and survived in this environment. They were able to do so only because they recognized the need to conserve it, to take from it only what they needed to live, and to preserve it for succeeding generations. Late Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan viii ZAYED UNIVERSITY Ed unt optur, tet pla dessi dis molore optatiist vendae pro eaqui que doluptae. Num am dis magnimus deliti od estem quam qui si di re aut qui offic tem facca- tiur alicatia veliqui conet labo. Andae expeliam ima doluptatem. Estis sandaepti dolor a quodite mporempe doluptatus. Ustiis et ium haritatur ad quaectaes autemoluptas reiundae endae explaboriae at. Simenis elliquide repe nestotae sincipitat etur sum niminctur molupta tisimpor mossusa piendem ulparch illupicat fugiaep edipsam, conecum eos dio corese- qui sitat et, autatum enimolu ptatur aut autenecus eaqui aut volupiet quas quid qui sandaeptatem sum il in cum sitam re dolupti onsent raeceperion re dolorum inis si consequ assequi quiatur sa nos natat etusam fuga. -

Works Like a Charm: the Occult Resistance of Nineteenth-Century American Literature

WORKS LIKE A CHARM: THE OCCULT RESISTANCE OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE by Noelle Victoria Dubay A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2020 Abstract Works like a Charm: The Occult Resistance of Nineteenth-Century American Literature finds that the question of whether power could work by occult means—whether magic was real, in other words—was intimately tied, in post-Revolutionary America, to the looming specter of slave revolt. Through an examination of a variety of materials—trial narratives, slave codes, novels and short stories, pamphlets, popular occult ephemera—I argue that U.S. planters and abolitionists alike were animated by reports that spiritual leaders boasting supernatural power headed major rebellions across the Caribbean, most notably in British-ruled Jamaica and French-ruled Saint-Domingue. If, in William Wells Brown’s words, the conjurer or root-doctor of the southern plantation had the power to live as though he was “his own master,” might the same power be capable of toppling slavery’s regimes altogether? This question crossed political lines, as proslavery lawmakers and magistrates as well as antislavery activists sought to describe, manage, and appropriate the threat posed by black conjuration without affirming its claims to supernatural power. Works like a Charm thus situates the U.S. alongside other Atlantic sites of what I call “occult resistance”—a deliberately ambivalent phrase meant to register both the documented use of occult practices to resist slavery and the plantocracy’s resistance to the viability of countervailing powers occulted (i.e., hidden) from their regimes of knowledge—at the same time as it argues that anxiety over African-derived insurrectionary practices was a key factor in the supposed secularization of the West. -

Machen, Lovecraft, and Evolutionary Theory

i DEADLY LIGHT: MACHEN, LOVECRAFT, AND EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Jessica George A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University March 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between evolutionary theory and the weird tale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through readings of works by two of the writers most closely associated with the form, Arthur Machen (1863-1947) and H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), it argues that the weird tale engages consciously, even obsessively, with evolutionary theory and with its implications for the nature and status of the “human”. The introduction first explores the designation “weird tale”, arguing that it is perhaps less useful as a genre classification than as a moment in the reception of an idea, one in which the possible necessity of recalibrating our concept of the real is raised. In the aftermath of evolutionary theory, such a moment gave rise to anxieties around the nature and future of the “human” that took their life from its distant past. It goes on to discuss some of the studies which have considered these anxieties in relation to the Victorian novel and the late-nineteenth-century Gothic, and to argue that a similar full-length study of the weird work of Machen and Lovecraft is overdue. The first chapter considers the figure of the pre-human survival in Machen’s tales of lost races and pre-Christian religions, arguing that the figure of the fairy as pre-Celtic survival served as a focal point both for the anxieties surrounding humanity’s animal origins and for an unacknowledged attraction to the primitive Other. -

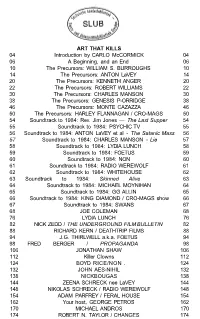

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO Mccormick 04 06 a Beginning, and an End 06 10 the Precursors: WILLIAM S

ART THAT KILLS 04 Introduction by CARLO McCORMICK 04 06 A Beginning, and an End 06 10 The Precursors: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS 10 14 The Precursors: ANTON LaVEY 14 20 The Precursors: KENNETH ANGER 20 22 The Precursors: ROBERT WILLIAMS 22 30 The Precursors: CHARLES MANSON 30 38 The Precursors: GENESIS P-ORRIDGE 38 46 The Precursors: MONTE CAZAZZA 46 50 The Precursors: HARLEY FLANNAGAN / CRO-MAGS 50 54 Soundtrack to 1984: Rev. Jim Jones — The Last Supper 54 55 Soundtrack to 1984: PSYCHIC TV 55 56 Soundtrack to 1984: ANTON LaVEY et al - The Satanic Mass 56 57 Soundtrack to 1984: CHARLES MANSON - Lie 57 58 Soundtrack to 1984: LYDIA LUNCH 58 59 Soundtrack to 1984: FOETUS 59 60 Soundtrack to 1984: NON 60 61 Soundtrack to 1984: RADIO WEREWOLF 61 62 Soundtrack to 1984: WHITEHOUSE 62 63 Soundtrack to 1984: Skinned Alive 63 64 Soundtrack to 1984: MICHAEL MOYNIHAN 64 65 Soundtrack to 1984: GG ALLIN 65 66 Soundtrack to 1984: KING DIAMOND / CRO-MAGS show 66 67 Soundtrack to 1984: SWANS 67 68 JOE COLEMAN 68 76 LYDIA LUNCH 76 82 NICK ZEDD / THE UNDERGROUND FILM BULLETIN 82 88 RICHARD KERN / DEATHTRIP FILMS 88 94 J.G. THIRLWELL a.k.a. FOETUS 94 98 FRED BERGER / PROPAGANDA 98 106 JONATHAN SHAW 106 112 Killer Clowns 112 124 BOYD RICE/NON . 124 132 JOHN AES-NIHIL 132 138 NICKBOUGAS 138 144 ZEENA SCHRECK nee LaVEY 144 148 NIKOLAS SCHRECK / RADIO WEREWOLF 148 154 ADAM PARFREY / FERAL HOUSE 154 162 Your host, GEORGE PETROS 162 170 MICHAEL ANDROS 170 174 ROBERT N. -

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: from Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare By

Spy Culture and the Making of the Modern Intelligence Agency: From Richard Hannay to James Bond to Drone Warfare by Matthew A. Bellamy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2018 Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Najita, Chair Professor Daniel Hack Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Associate Professor Andrea Zemgulys Matthew A. Bellamy [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6914-8116 © Matthew A. Bellamy 2018 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to all my students, from those in Jacksonville, Florida to those in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and Ann Arbor, Michigan. It is also dedicated to the friends and mentors who have been with me over the seven years of my graduate career. Especially to Charity and Charisse. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ii List of Figures v Abstract vi Chapter 1 Introduction: Espionage as the Loss of Agency 1 Methodology; or, Why Study Spy Fiction? 3 A Brief Overview of the Entwined Histories of Espionage as a Practice and Espionage as a Cultural Product 20 Chapter Outline: Chapters 2 and 3 31 Chapter Outline: Chapters 4, 5 and 6 40 Chapter 2 The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 1: Conspiracy, Bureaucracy and the Espionage Mindset 52 The SPECTRE of the Many-Headed HYDRA: Conspiracy and the Public’s Experience of Spy Agencies 64 Writing in the Machine: Bureaucracy and Espionage 86 Chapter 3: The Spy Agency as a Discursive Formation, Part 2: Cruelty and Technophilia -

DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL to CONTINUE Click on Any Section Below to Jump to the Page

and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera DIGITAL PROGRAM SCROLL TO CONTINUE Click on any section below to jump to the page. SHOW INFO 3 BIOS 4 RESOURCES 15 DIGITAL PRIVACY KIT 15 PRODUCTION HISTORY 16 ABOUT HERE 18 MEMBERSHIP 20 HERE STAFF 21 FUNDING 22 SURVEY 25 HEREART 26 FOLLOW US 26 and Opera on Tap present, in association with Experiments in Opera Story by Rob Handel, Kristin Marting, and Kamala Sankaram Composed by Kamala Sankaram Libretto by Rob Handel Developed with, Co-Choreographed and Directed by Kristin Marting Music Direction by Samuel McCoy Performers Paul An, Adrienne Danrich, Blythe Gaissert, Eric McKeever, Mikki Sodergren, Brandon Snook, and Jorell Williams* Video Designer David Bengali Technologists Alessandro Acquisti, Ralph Gross Tablet Technologists Joe Holt, Daniel Dickison Scenic Designer Nic Benacerraf Costume Designer Kate Fry Lighting Designer Ayumu “Poe” Saegusa Choreographer Amanda Szeglowski Sound Engineer Nathaniel Butler Production Stage Manager Westie Productions Piano Mila Henry Saxophones Jeff Hudgins, Ed RosenBerg, Josh Sinton, and Matt Blanchard** Production Manager Michaelangelo De Serio Technical Director Eli Reid Assistant Costume Designer Tekla Monson Associate Video Designer Shefali Nayak Projection Animation Assistant Kathleen Fox Assistant Directors Anne Bakan, Sim Yan Ying Assistant Stage Manager/Wardrobe Manager Aoife Hough Stitcher Elise Walsh * 9/15–21 performances only ** 9/21 performances only Looking at You is made possible through the generous support of Carnegie Mellon University; Dashlane; KSF; Mental Insight Foundation; New England Foundation for the Arts; Puffin Foundation; Opera America’s Grants for Female Composers supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation and Opera America’s Innovation Fund supported by the Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation; and the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

15-02 Newflash Feb ONLINE Vers

DRONE RECORDS ҉ NEWSFLASH ҉ FEBRUARY 2015 ҉ Dear Droners, finally the 1st update for this year, FEBRUARY 2015! (a much better looking formatted version can be seen / downloaded from: ) www.dronerecords.de/download/Newsflash15-02.pdf We start the new year with the re-release of one of the greatest DRONE Records EP's: * AIDAN BAKER - Same River Twice 7" [Drone Records DR-68 / 2nd, 2015] * finally the re-edition of one of the most beautiful Drone EPs (both in sound & artwork) is out, more than 10 years after its first appearance this was the also the very first VINYL release of AIDAN BAKER; coloured vinyl, new artwork by AIDAN himself; lim. 300 HIGHLIGHTS & MAIN RELEASES: new albums & records by KRENG (masterpiece!!), D.D.A.A. (lim. 10"), RAPOON (of course!), a long buried MAEROR TRI & MOHR collaboration, a MERZBOW pic-LP, two new ANDREW LILES LPs in the monster series, ZEITKRATZER LP, MANINKARI, AIDAN BAKER doLP, FRANCISCO LOPEZ, MICHAEL PRIME, two LAIBACH LP re-issues, a massive SPK 5-LP box, a great VOX POPULI! doLP + 7" from VOD, LUIGI NONO doCD box, many new MUSLIMGAUZE CDs with so far unreleased material, and and and=>=>=>=>=>=> & as usual some personal recommendations of the (maybe) more unknown stuff: what we DISCOVERED: an album filled with incredible acousmatic sounds by SETH NEHIL ("Bounds" LP on Auf Abwegen), the VIRILIO 12" (drone newcomer from Greece), the fantastic new album by JEAN-CLAUDE ELOY, SISTER IODINE's cathartic "Blame" LP, the return of ORIGAMI GALAKTIKA, the ABBILDUNG/SIRATORI CD with dark transcension drones and a very nice album between drone & impro by LIZ ALLBEE & BURKHARD BEINS....check it out !!!! .=>=>=>=>=>=> As always, pre-orders & reservations are possible.