Shamans and Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloth Bear Zoo Experiences 3000

SLOTH BEAR ZOO EXPERIENCES 3000 Behind the Scenes With the Tigers for Four (BEHIND THE SCENES) Head behind the scenes for a face-to-face visit with Woodland Park Zoo’s new Malayan tigers. This intimate encounter will give you exclusive access to these incredible animals. Meet our expert keepers and find out what it’s like to care for this critically endangered species. You’ll learn about Woodland Park Zoo and Panthera’s work with on-the-ground partners in Malaysia to conserve tigers and the forests which these iconic big cats call home, and what you can do to help before it’s too late. Restrictions: Expires July 10, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance. Participants must be 12 years of age and older. THANK YOU: WOODLAND PARK ZOO EAST TEAM VALUE: $760 3001 Behind the Scenes Giraffe Feeding for Five (BEHIND THE SCENES) You and four guests are invited to meet the tallest family in town with this rare, behind-the-scenes encounter. Explore where Woodland Park Zoo’s giraffe spend their time off exhibit and ask our knowledgeable keepers everything you’ve ever wanted to know about giraffe and their care. You’ll even have the opportunity to help the keepers feed the giraffe a snack! This is a tall experience you won’t forget, and to make sure you don’t, we’ll send you home with giraffe plushes! Restrictions: Expires April 30, 2016. Please make mutually agreeable arrangements at least eight weeks in advance from 9:30 a.m.–2:00 p.m. -

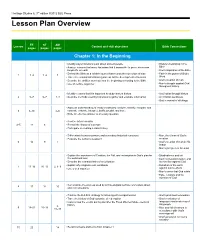

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia Without Proper Restraint Device

J Vet Clin 26(1) : 113-116 (2009) Baby Giraffe Rope-Pulled Out of Mother Suffering from Dystocia without Proper Restraint Device Hwan-Yul Yong1, Suk-Hyun Park, Myoung-Keun Choi, So-Young Jung, Dae-Chang Ku, Jong-Tae Yoo, Mi-Jin Yoo, Mi-Hyun Yoo, Kyung-Yeon Eo, Yong-Gu Yeo, Shin-Keun Kang and Heon-Youl Kim Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon 427-080, Korea (Accepted : January 28, 2009 ) Abstract : A 4-year-old female reticulated giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata), at Seoul Zoo, Gwacheon, Korea had a male calf with no help of proper restraint devices. The mother giraffe was in a danger of dystocia more than 7 hours in labor after showing the calf’s toe of the foreleg which protruded from her vulva. After tugging with a snare of rope on the metacarpal bone of the calf and pulling it, the other toe emerged. Finally, with two snares around each of metacarpal bones, the calf was completely pulled out by zoo staff. After parturition, the dam was in normal condition for taking care of the calf and her progesterone hormone had also dropped down to a normal pre-pregnancy. Key words : giraffe, dystocia, rope, parturition. Introduction giraffe. Because a giraffe is generally known as having such an uneventful gestation and not clearly showing appearances Approaching the megavertebrate species such as ele- of body with which zoo keepers notice impending parturi- phants, rhinoceroses and giraffes without anesthetic agents or tion until just several weeks before parturition. A few of zoo proper physical restraint devices is very hard, and it is even keepers were not suspicious of her being pregnant when they more difficult when it is necessary to stay near to the ani- saw the extension of the giraffe’s abdomen around 2 weeks mals for a long period (1,2,5). -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Exposing Exoticism – the Near and the Far in the Exhibition Context

Exposing exoticism – the near and the far in the exhibition context Elisa de Souza MARTINEZ University of Brasilia, Brazil National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil This article analyzes a set of situations drawn from the exhibition La Triennale 2012 – Intense Proximité, held at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, from April 20 to August 26, 2012. In this exhibition, the curatorial discourse is seen as playing a mediating role, making the vision possible, i.e. providing the context of the scopic relations to be descibed. Its role is to make the vision possible, i.e. it provides the context of the scopic relations to be described. In this case, the enunciator-curator defines the conditions in which the displayed objects are seen, and in which the visitors see. Thus, the analysis of situations (Landowski 1996) that constitute visibility regimes defines the scopic relations. La Triennale highlights the ethnographic image, which is seen as an art object, while at the same time art objects are seen as ethnographic documents. Displayed in a contemporary art event, ethnographic images express ethnographic content, and therefore play an ambiguous role. In any case, the function assigned to the image, whether artistic or ethnographic, allows one to consider, at the fundamental level of analysis, a semantic category that unfolds into two opposite terms: fictional and documental. The objects chosen by the addresser-curator, Okwui Enwezor, confront the addressee- visitor with a broader problem than the distinction between artistic or ethnographic function. Considering that these functions manifest themselves simultaneously to variable degrees in each element of the exhibition-text, one finds that the same image can have a dual function, hindering its classification in a single field of epistemological relations. -

What Is a Totem Pole?

What is a totem pole? A totem is an emblem of A totem pole is a monument a family or clan. This of a single log of red cedar that emblem can feature a is carved by First Nations natural object, an animal peoples of the Pacific Northwest or a spirit being. Coast. A pole includes an arrangement of several totems. What is it used for? A totem pole can be used for different purposes: to welcome visitors, as a memorial for important members of the tribe, as a tomb Sisiutl, a double-headed or headstone, to celebrate a special occasion, serpent, one of the many crests of the Hunt family. or as a supporting column inside houses. What figures are displayed on a totem pole? A totem pole typically features symbolic and stylized human, animal, and supernatural forms. They are visual representations of family stories and ancestry. Families acquire the rights to display specific figures, or crests, over many generations. These Henry Hunt totem pole crests can be acquired through supernatural encounters that Photo by Mark Davidson, 2019 ancestors had and were handed down to their descendants, through marriage, or in a potlatch. A potlatch was a ceremony to mark important life events, including the new use of a family crest. Some common figures are: Human figures Sky elements Animals of the forest and mountains Chief Sun, moon Bear, wolf Sea beings Sky beings Supernatural Seal, whale, salmon Eagle, raven, owl Thunderbird, Sisiutl (double-headed serpent) How are they designed? Figures are characterized by two elements: Formline Basic colors A combination of thin and thick Black - Used for the formline lines that help to divide figures Red – Adds detail and structure the design. -

Vampires Now and Then

Hugvisindasvið Vampires Now and Then From origins to Twilight and True Blood Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Daði Halldórsson Maí 20 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska Vampires Now and Then From origins to Twilight and True Blood Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Daði Halldórsson Kt.: 250486-3599 Leiðbeinandi: Úlfhildur Dagsdóttir Maí 2010 This essay follows the vampires from their origins to their modern selves and their extreme popularity throughout the years. The essay raises the question of why vampires are so popular and what it is that draws us to them. It will explore the beginning of the vampire lore, how they were originally just cautionary tales told by the government to the villagers to scare them into a behavior that was acceptable. In the first chapter the mythology surrounding the early vampire lore will be discussed and before moving on in the second chapter to the cult that has formed around the mythological and literary identities of these creatures. The essay finishes off with a discussion on the most recent popular vampire related films Twilight and New Moon and TV-series True Blood and their male vampire heroes Edward Cullen and Bill Compton. The essay relies heavily on The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and other Monsters written by Rosemary Ellen Guiley as well as The Dead Travel Fast: Stalking Vampires from Nosferatu to Count Chocula written by Eric Nuzum as well as the films Twilight directed by Catherine Hardwicke and New Moon directed by Chris Weitz and TV-series True Blood. Eric Nuzum's research on the popularity of vampires inspired the writing of this essay. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: a Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 5 9-1-1996 Shamanic Wisdom, Parapsychological Research and a Transpersonal View: A Cross-Cultural Perspective Larissa Vilenskaya Psi Research Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Vilenskaya, L. (1996). Shamanic wisdom, parapsychological research and a transpersonal view: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15(3), 30–55.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 15 (3). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies/vol15/iss3/5 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SHAMANIC WISDOM, PARAPSYCHOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND A TRANSPERSONAL VIEW: A CROSS-CULTURAL ' PERSPECTIVE LARISSA VILENSKAYA PSI RESEARCH MENLO PARK, CALIFORNIA, USA There in the unbiased ether our essences balance against star weights hurled at the just now trembling scales. The ecstasy of life lives at this edge the body's memory of its immutable homeland. -Osip Mandelstam (1967, p. 124) PART I. THE LIGHT OF KNOWLEDGE: IN PURSUIT OF SLAVIC WISDOM TEACHINGS Upon the shores of afar sea A mighty green oak grows, And day and night a learned cat Walks round it on a golden chain. -

Academic and Neo-Pagan Interpretations of Shamanism In

Academic and neo•pagan interpretations of shamanism in Buile Suibhne: a comparative approach1 Alexandra Bergholm University of Helsinki, Department of Comparative Religion, [email protected] Introduction n the introductory chapter to the book titled New Directions in Celtic Studies (1999), editors Amy Hale and Philip Payton expressed their concern about the general unwillingness within Celtic Studies to address the array of modern “Celticity” (Hale & Payton 1999, 1–2). I Although several scholars have already begun to acknowledge that ‘the constructed nature of contemporary Celtic identities’ in all its complexity is a topic worth studying, critics argue that the field is still dominantly focused on analysing medieval literature by outdated methods of comparative cultural analysis (Ibid, 2, 8, 10). While I personally do not embrace the claims that Celtic Studies as an academic discipline lacks methodological progress and critical discourse, I do agree with the view that modern expressions of “Celticity”, rather than being rejected at the outset as unauthentic or fabricated, deserve attention alongside with the more traditional topics of Celtic scholarship.2 In this article, I will elaborate on this outlook by bringing one aspect of modern Celtic spirituality3 • the Neo•Pagan reception of the 12th century tale Buile Suibhne (The Frenzy of Suibhne) • into comparison with scholarly discussions of the same text. Though it is arguable that the academic and Neo•Pagan approaches to early Irish material differ substantially in the aims of their inquiries, I would claim that in terms of literary interpretation, the scholarly and Neo•Pagan views of the tale’s main protagonist Suibhne as a shamanic figure share common ground in their underlying presuppositions concerning the nature of shamanism and the 1 The writing of this article has been funded by the Academy of Finland, project number 1211006. -

Dealing with Uncertainty: Shamans, Marginal Capitalism, and the Remaking of History in Postsocialist Mongolia

MANDUHAI BUYANDELGERIYN Harvard University Dealing with uncertainty: Shamans, marginal capitalism, and the remaking of history in postsocialist Mongolia ABSTRACT ore than 15 years have passed since the collapse of social- In this article, I explore the proliferation of ism in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and Mongolia.1 Most previously suppressed shamanic practices among people in these regions have been subjected to unexpected, ethnic Buryats in Mongolia after the collapse of contradictory, and often confusing transformations because socialism in 1990. Contrary to the Buryats’ of the “unmaking” (Humphrey 2002) of socialism and the si- expectation that shamanism would solve the Mmultaneous arrival of a market economy and implementation of neoliberal uncertainties brought about by the market economy, economic reforms. Because the economic transformations have been the it has created additional spiritual uncertainties. As most visible and pertinent aspects of the transitions to postsocialism, a rich skeptical Buryats repeatedly propitiate their angry body of work has discussed the restructuring of property and privatization, origin spirits to alleviate the causes of their state institutions, and the rethinking of political categories (Berdahl 1999; misfortunes, they reconstruct their history, which Borneman1992,1998;BurawoyandVerdery1999;Caldwell2004;Humphrey was suppressed by state socialism. The Buryats make 2002; Verdery 1996). Scholars elsewhere have also noted that the feelings of their current calamities meaningful by placing them uncertainty, insecurity, and anxiety that result from the dangerous volatil- within the shifting history of their tragic past. The ity, disorder, and opaqueness of the market are being articulated through sense of uncertainty, fear, and disillusionment the medium of popular religion, shamanism, witchcraft, and spirit posses- experienced by the Buryats also characterizes daily sion (Comaroff and Comaroff 2000; Kendall 2003; Moore and Sanders 2001; life in places other than Mongolia.