The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

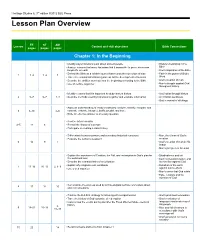

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Knowledge of Skull Base Anatomy and Surgical Implications of Human Sacrifice Among Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican Cultures

See the corresponding retraction, DOI: 10.3171/2018.5.FOCUS12120r, for full details. Neurosurg Focus 33 (2):E1, 2012 Knowledge of skull base anatomy and surgical implications of human sacrifice among pre-Columbian Mesoamerican cultures RAUL LOPEZ-SERNA, M.D.,1 JUAN LUIS GOMEZ-AMADOR, M.D.,1 JUAN BArgES-COLL, M.D.,1 NICASIO ArrIADA-MENDICOA, M.D.,1 SAMUEL ROMERO-VArgAS, M.D., M.SC.,2 MIGUEL RAMOS-PEEK, M.D.,1 MIGUEL ANGEL CELIS-LOPEZ, M.D.,1 ROGELIO REVUELTA-GUTIErrEZ, M.D.,1 AND LESLY PORTOCArrERO-ORTIZ, M.D., M.SC.3 1Department of Neurosurgery, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia “Manuel Velasco Suárez;” 2Department of Spine Surgery, Instituto Nacional de Rehabilitación; and 3Department of Neuroendocrinology, Instituto Nacional de Neurologia y Neurocirugia “Manuel Velasco Suárez,” Mexico City, Mexico Human sacrifice became a common cultural trait during the advanced phases of Mesoamerican civilizations. This phenomenon, influenced by complex religious beliefs, included several practices such as decapitation, cranial deformation, and the use of human cranial bones for skull mask manufacturing. Archaeological evidence suggests that all of these practices required specialized knowledge of skull base and upper cervical anatomy. The authors con- ducted a systematic search for information on skull base anatomical and surgical knowledge among Mesoamerican civilizations. A detailed exposition of these results is presented, along with some interesting information extracted from historical documents and pictorial codices to provide a better understanding of skull base surgical practices among these cultures. Paleoforensic evidence from the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan indicates that Aztec priests used a specialized decapitation technique, based on a deep anatomical knowledge. -

La Huasteca: Correlations of Linguistic and Archaeological Data

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Calgary (Working) Papers in Linguistics Volume 11, Summer 1985 1985-06 La Huasteca: correlations of linguistic and archaeological data Thompson, Marc University of Calgary Thompson, M. (1985). La Huasteca: correlations of linguistic and archaeological data. Calgary Working Papers in Linguistics, 11(Summer), 15-25. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51328 journal article Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca I I La Rua•tec:&: Con:elatiou of Li1S9Ubtic and Archaeoloqical Data I Marc Thompson Introduction I In modern Mexico and Guatemala there are between 2 and 2.5 million speakers of 28 Mayan lanCJU&qes. As a qroup they rank next to Quechua speakers of Peru and Equador as one of the most I impressive survivinq Amerindian linquistic and cultural units in the western hemisphere (Voqt 1969). As qeoqraphy and modern distribution suqqest, with the exception of the HUastecs, various Maya qroups have been in contact for many centuries. Linquists qenerally define three major subqroups of Mayan: l) Huastecan, I 2) Yucatecan and 3) southern Mayan. Today, Huastecan speakers are comprised of two linquistic units: l) Veracruzano, distributed alonq the tropical coastlands, and I 2) Potosino, spoken in the interior hiqhlands, correspondinq to the states of Veracruz, and San Luis Potosi, Mexico, respectively. Modern distribution of Huastacan speakers is represented by small, rather nucleated vestiqes of Precollllllbian territories: I "Only five towns in northern Veracruz and an equal nlllllber in Potosi could boast a population of l8 per cent or more Huastec speakinq inhabitants, and no town reqistered over 72 per cent. -

Reframing Mexican Migration As a Multi-Ethnic Process

UC Santa Cruz Reprint Series Title Reframing Mexican Migration as a Multi-Ethnic Process Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nn6v8sk Author Fox, Jonathan A Publication Date 2006-02-23 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Article REFRAMING MEXICAN MIGRATION 1 AS A MULTI-ETHNIC PROCESS 1 A longer version of this paper was presented at the Latin American Studies Association in Jonathan Fox 2004. Some sections draw University of California at Santa Cruz, CA from Fox and Rivera-Salgado (2004). Abstract The Mexican migrant population in the US increasingly reflects the ethnic diversity of Mexican society. To recognize Mexican migration as a multi-ethnic process raises broader conceptual puzzles about race, ethnicity, and national identity. This essay draws from recent empirical research and participant-observation to explore implications of the indigenous Mexican migrant experience for understanding collective identity formation, including the social construction of community member- ship, regional and pan-ethnic identities, territory, and transnational communities. Keywords indigenous; migration; Mexico; collective identity Introduction In the US, when the terms ‘‘multi-ethnic,’’ ‘‘multi-cultural,’’ and ‘‘multi- racial’’ are used to refer to Mexican migrants, they refer exclusively to relationships between Mexicans and other racial and national origin groups. Yet Mexican society is multi-ethnic and multi-racial. From an indigenous rights perspective, the Mexican nation includes many peoples. To take the least ambiguous indicator of ethnic difference, more than one in ten Mexicans come from a family in which an indigenous language is spoken (Serrano Carreto et al., 2003). Many of the indigenous Mexican activists in the US on the cutting edge are trilingual, and for some, Spanish is neither their first nor their second language. -

A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(S): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol

Society for American Archaeology A Linguistic Look at the Olmecs Author(s): Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Jan., 1976), pp. 80-89 Published by: Society for American Archaeology Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/279044 Accessed: 24/02/2010 18:09 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sam. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Antiquity. http://www.jstor.org 80 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol. 41, No. 1, 1976] Palomino, Aquiles Smith, Augustus Ledyard, and Alfred V. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Wab Forum Armies the Tarascan Army of the Conquest

WAB FORUM ARMIES THE TARASCAN ARMY OF THE CONQUEST HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Mexican Basin. However, it was a rocky volcanic land, punctuated by smaller fertile valleys, and home to only 1.3 million people. In this respect it could never rival the power of the Triple Alliance. The Tarascans spread their language and administrative skills into a cohesive uniform polity that encompassed a variety of ethnic groups, all maintained from the administrative offices within the main city of Tzintzuntzan. It was a highly stratified society with a small hereditary nobility ruling on behalf of a large population of commoners. There was also a very large slave population. The minor nobility formed a The Pyramids of Tzintzuntzan, the “Place of the Hummingbirds” professional military force, with the commoners delivering their military service as a form of tribute to the government. Unlike Together with the Tlaxcalteca, the people of the Michoacan the Mexica, the Tarascans employed uniformly armed combat Valley, the Tarascans, could be considered one of the most units and relied much more heavily on archery. As an aside, the dangerous enemy of the Triple Alliance Mexica. Ironically, they Tarascans were so named due to another error by the “cloth- fought the much larger Mexica armies to a standstill for about 90 eared” Spanish. The Tarascans facetiously called the Spaniards years but then surrendered their entire empire to the Spanish “Tarascue” or “sons-in-law” due to the Spaniards reputation of Crown within 1 year of the Aztec collapse. stealing native daughters. Somehow, the Conquistadores thought this was the name the Tarascans used for themselves, and so the The Tarascans were, like the Nahuatl speaking Chichimec tribes term stuck. -

Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World

S Y M P O S I U M A B S T R A C T S Contested Visions in the Spanish Colonial World _______________________________________________________________________________________ Cecelia F. Klein, University of California, Los Angeles Huitzilopochli’s magical birth and victory, and Suffer the Little Children: Contested Visions of Child the world-mountain of cosmic renewal. Such Sacrifice in the Americas contrasting, alternating themes, the subject that I explore here, were similarly expressed at other This talk will address the ways that artists over the sacred mountains in the Valley of Mexico. The centuries have depicted the sacrifice of children in juxtaposed celebrations of conquest and tributary the preconquest Americas, and what those images rulership, alternating with the call for world can tell us about the politics of visual representation regeneration, were complementary aims engaged in complex arenas where governments and social in the annual cycle, expressing the dynamic factions struggle to negotiate a more advantageous obligations of Aztec kings in maintaining the place for themselves. The focus will be on the formal integration of society and nature. differences between New and Old World representa- tions of Aztec and Inca child sacrifice and the ways in which western artistic conventions and tropes Carolyn Dean, University of California, Santa Cruz long used in Europe to visualize its “Others” were Inca Transubstantiation deployed in the making of images of Native American child sacrifice. Colonial and early modern images of In Pre-Hispanic times the Inca believed that the subject, it will be argued, were largely shaped, objects could host spiritual essences. Although not by the desire to record historical “truths” about rocks were the most common hosts, a wide child sacrifice among the Aztec and the Inca, but by variety of things (including living bodies) were their makers and patrons’ own ambitions at home, capable of housing sacred anima. -

Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications World Languages and Literatures 3-1-2007 Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish Anne Fountain San Jose State University, [email protected] Catherine Fountain Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/world_lang_pub Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Anne Fountain and Catherine Fountain. "Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish" From Practice to Profession: Dimension 2007 (2007): 63-77. This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Literatures at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 6 Maya and Nahuatl in the Teaching of Spanish: Expanding the Professional Perspective Anne Fountain San Jose State University Catherine Fountain Appalachian State University Abstract Indigenous languages of the Americas are spoken by millions of people 500 years after the initial period of European conquest. The people who speak these languages and the customs they continue to practice form a rich cultural texture in many parts of Spanish America and can be important components of an instructor’s Standards-based teaching. This article discusses the influence of Maya and Nahuatl languages and cultures on the language, literature, and history of Mexico and Central America. Examples of this influence range from lexical and phonological traits of Mexican Spanish to the indigenous cultures and worldviews conveyed in texts as varied as the Mexican soap opera “Barrera de Amor” and the stories by Rosario Castellanos of Mexico and Miguel Angel Asturias of Gua temala. -

Read Book Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1St Edition Kindle

RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT GREEK CITY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Louise Bruit Zaidman | 9780521423571 | | | | | Religion in the Ancient Greek City 1st edition PDF Book Altogether the year in Athens included some days that were religious festivals of some sort, though varying greatly in importance. Some of these mysteries, like the mysteries of Eleusis and Samothrace , were ancient and local. Athens Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. At some date, Zeus and other deities were identified locally with heroes and heroines from the Homeric poems and called by such names as Zeus Agamemnon. The temple was the house of the deity it was dedicated to, who in some sense resided in the cult image in the cella or main room inside, normally facing the only door. Historical religions. Christianization of saints and feasts Christianity and Paganism Constantinian shift Hellenistic religion Iconoclasm Neoplatonism Religio licita Virtuous pagan. Sacred Islands. See Article History. Sim Lyriti rated it it was amazing Mar 03, Priests simply looked after cults; they did not constitute a clergy , and there were no sacred books. I much prefer Price's text for many reasons. At times certain gods would be opposed to others, and they would try to outdo each other. An unintended consequence since the Greeks were monogamous was that Zeus in particular became markedly polygamous. Plato's disciple, Aristotle , also disagreed that polytheistic deities existed, because he could not find enough empirical evidence for it. Once established there in a conspicuous position, the Olympians came to be identified with local deities and to be assigned as consorts to the local god or goddess.