Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A

La Corona Notes 1(1) The Importance of La Corona1 Marcello A. Canuto Middle American Research Institute / Tulane University Tomás Barrientos Q. Universidad del Valle de Guatemala In 2008, the Proyecto Regional Arqueológico monuments led to the realization that these texts La Corona (PRALC; directed by Marcello A. contained several terms not only common in, but Canuto and Tomás Barrientos Q.) was established also unique to the texts of Site Q (Stuart 2001). to coordinate archaeological research in the The locative term thought to be the ancient Maya northwestern sector of the Guatemalan Peten. name of Site Q (sak nikte’), the name of a Site Q ruler Centered at the site of La Corona (N17.52 W90.38), (Chak Ak’aach Yuk), titles characteristic of Site Q PRALC initiated the first long-term scientific rulers (sak wayis), and references to Site Q’s most research of both the site and the surrounding important ally (Kaanal), were all present in the region. To a large extent, however, La Corona texts found at La Corona. Despite expressed doubts was well known long before PRALC began its regarding the identification of La Corona as Site Q investigations, since it was ultimately revealed to (Graham 2002), petrographic similarities between be the mysterious “Site Q.” As the origin of over stone samples from a Site Q monument and from two dozen hieroglyphic panels looted in the 1960s exemplars collected at the site of La Corona led and attributed to the as-yet-unidentified “Site Q” Stuart (2001) to suggest that La Corona was Site Q. -

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

Kahk' Uti' Chan Yopat

Glyph Dwellers Report 57 September 2017 A New Teotiwa Lord of the South: K’ahk’ Uti’ Chan Yopat (578-628 C.E.) and the Renaissance of Copan Péter Bíró Independent Scholar Classic Maya inscriptions recorded political discourse commissioned by title-holding elite, typically rulers of a given city. The subject of the inscriptions was manifold, but most of them described various period- ending ceremonies connected to the passage of time. Within this general framework, statements contained information about the most culturally significant life-events of their commissioners. This information was organized according to discursive norms involving the application of literary devices such as parallel structures, difrasismos, ellipsis, etc. Each center had its own variations and preferences in applying such norms, which changed during the six centuries of Classic Maya civilization. Epigraphers have thus far rarely investigated Classic Maya political discourse in general and its regional-, site-, and period-specific features in particular. It is possible to posit very general variations, for example the presence or absence of secondary elite inscriptions, which makes the Western Maya region different from other areas of the Maya Lowlands (Bíró 2011). There are many other discursive differences not yet thoroughly investigated. It is still debated whether these regional (and according to some) temporal discursive differences related to social phenomena or whether they strictly express literary variation (see Zender 2004). The resolution of this question has several implications for historical solutions such as the collapse of Classic Maya civilization or the hypothesis of status rivalry, war, and the role of the secondary elite. There are indications of ruler-specific textual strategies when inscriptions are relatively uniform; that is, they contain the same information, and their organization is similar. -

LA 119 Maymester Seminar Guatemala and Belize Dr. David

LA 119 Maymester Seminar Guatemala And Belize Dr. David Stuart, Department of Art and Art History Dr. Stuart’s Office Office Hours email ART 1.412B (Mesoamerica Center) T 1:00-2:30 PM [email protected] Class Times: Tuesdays 2:30 PM - 4:30 PM in ART 2.208 Class meets eight times on the Following dates: January 29, February 12, February 26, March 12, March 26, April 9, April 23, and May 7 Topic Description: Maya civilization emerged on the scene over 3,000 years ago within what is today southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador. The Maya soon developed one of the great civilizations of the ancient world, well known for its impressive ruins, temple pyramids and palaces, stone sculptures, and elaborate hieroglyphic writing system. The Maya experienced profound changes and disruptions throughout their history and development, including the so-called “collapse” of many cities around 800-900 AD. The arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century and the British in the 18th century then brought near destruction to their world, but Maya peoples emerged resilient in the wake of conquest in what are now the modern nations of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Today six million strong, the modern Maya continue to express their cultural identity in the art and politics of modern Mexico and Central America. Their cultural legacy has left its mark on northern Central America in many ways, and the tortured indigenous history of the region continues to shape the politics of our own time. Course Objectives: This class prepares students on the history of the Maya of Guatemala and Belize, spanning the Pre-Columbian, Colonial, and modern times, and provides the literature and visual culture background for the Maymester study abroad course on Maya Art and Architecture (ARH 347M) taking place in Guatemala and Belize. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

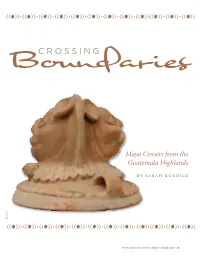

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Manufactured Light Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm

Edited by Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey MANUFACTURED MIRRORS IN THE LIGHT MESOAMERICAN REALM COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables xiii Chapter 1: Introduction Emiliano Gallaga M. 3 Chapter 2: How to Make a Pyrite Mirror: An Experimental Archaeology Project Emiliano Gallaga M. 25 Chapter 3: Manufacturing Techniques of Pyrite Inlays in Mesoamerica Emiliano Melgar, Emiliano Gallaga M., and Reyna Solis 51 Chapter 4: Domestic Production of Pyrite Mirrors at Cancuén,COPYRIGHTED Guatemala MATERIAL Brigitte KovacevichNOT FOR DISTRIBUTION73 Chapter 5: Identification and Use of Pyrite and Hematite at Teotihuacan Julie Gazzola, Sergio Gómez Chávez, and Thomas Calligaro 107 Chapter 6: On How Mirrors Would Have Been Employed in the Ancient Americas José J. Lunazzi 125 Chapter 7: Iron Pyrite Ornaments from Middle Formative Contexts in the Mascota Valley of Jalisco, Mexico: Description, Mesoamerican Relationships, and Probable Symbolic Significance Joseph B. Mountjoy 143 Chapter 8: Pre-Hispanic Iron-Ore Mirrors and Mosaics from Zacatecas Achim Lelgemann 161 Chapter 9: Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya Marc G. Blainey 179 Chapter 10: Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination John J. McGraw 207 Chapter 11: Reflecting on Exchange: Ancient Maya Mirrors beyond the Southeast Periphery Carrie L. Dennett and Marc G. Blainey 229 Chapter 12: Ritual Uses of Mirrors by the Wixaritari (Huichol Indians): Instruments of Reflexivity in Creative Processes COPYRIGHTEDOlivia Kindl MATERIAL 255 NOTChapter FOR 13: Through DISTRIBUTION a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica Karl Taube 285 List of Contributors 315 Index 317 vi contents 1 “Here is the Mirror of Galadriel,” she said. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

Ancient Writing

Ancient Writing As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This resource explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. You'll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt. Grade Level: Grades 3-5 Collection: Ancient Art, East Asian Art, Egyptian Art, Pre-Columbian Art Culture/Region: America, China, Egypt Subject Area: History and Social Science, Science, Visual Arts Activity Type: Art in Depth HOW ANCIENT WRITING BEGAN… AND ENDED As early civilizations developed, societies became more complicated. Record keeping and communication demanded something beyond symbols and pictures to represent the spoken word. This gallery explores the early writing systems of four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. Here you’ll also learn about the Rosetta Stone, the 19th-century discovery that gave scholars the key that unlocked the language of ancient Egypt. Why were writing systems developed? Communication – Sounds and speech needed to be visually represented. Correspondence – There was a desire to send notes, letters, and instructions. Recording – Bookkeeping tasks became important for counting crops, paying workers’ rations, and collecting taxes. Preservation – Personal stories, rituals, religious texts, hymns, literature, and history all needed to be recorded. Why did some writing systems disappear? Change – Corresponding cultures died out or were absorbed by others. Innovation – Newer, simpler systems replaced older systems. Conquest – Invaders or new rulers imposed their own writing systems. New Beginnings – New ways of writing developed with new belief systems. -

Changes and Continuities in Ritual Practice at Chechem Ha Cave, Belize

FAMSI © 2010: Esperanza Elizabeth Jiménez García Sculptural-Iconographic Catalogue of Tula, Hidalgo: The Stone Figures Research Year: 2007 Culture : Toltec Chronology : Post-Classic Location : México, Hidalgo Site : Tula Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction The Tula Archaeological Zone The Settlement Tula's Sculpture 1 The Conformation of the Catalogue Recording the Materials The Formal-architectural Classification Architectural Elements The Catalogue Proposed Chronological Periods Period 1 Period 2 Period 3 Acknowledgments List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract The goal of this study was to make a catalogue of sculptures integrated by archaeological materials made of stone from the Prehispanic city of Tula, in the state of Hidalgo, Mexico. A total of 971 pieces or fragments were recorded, as well as 17 panels or sections pertaining to projecting panels and banquettes found in situ . Because of the great amount of pieces we found, as well as the variety of designs we detected both in whole pieces and in fragments, it was necessary to perform their recording and classification as well. As a result of this study we were able to define the sculptural and iconographic characteristics of this metropolis, which had a great political, religious, and ideological importance throughout Mesoamerica. The study of these materials allowed us to have a better knowledge of the figures represented, therefore in this study we offer a tentative periodic scheme which may reflect several historical stages through which the city's sculptural and architectural development went between AD 700-1200. Resumen El objetivo de este trabajo, fue la realización de un catálogo escultórico integrado por materiales arqueológicos de piedra que procedieran de la ciudad prehispánica de Tula, en el estado de Hidalgo, México.