Lara Samples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

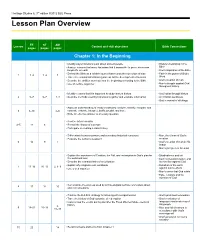

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides Spirituality through Art 2015 Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides Recommended Citation Contis, George M.D., "Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God" (2015). Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides/5 This Exhibit Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Spirituality through Art at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H . Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H. Booklet created for the exhibit: Icons from the George Contis Collection Revelation Cast in Bronze SEPTEMBER 15 – NOVEMBER 13, 2015 Marian Library Gallery University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio 45469-1390 937-229-4214 All artifacts displayed in this booklet are included in the exhibit. The Nativity of Christ Triptych. 1650 AD. The Mother of God is depicted lying on her side on the middle left of this icon. Behind her is the swaddled Christ infant over whom are the heads of two cows. Above the Mother of God are two angels and a radiant star. The side panels have six pairs of busts of saints and angels. Christianity came to Russia in 988 when the ruler of Kiev, Prince Vladimir, converted. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Dositheos Notaras, the Patriarch of Jerusalem (1669-1707), Confronts the Challenges of Modernity

IN SEARCH OF A CONFESSIONAL IDENTITY: DOSITHEOS NOTARAS, THE PATRIARCH OF JERUSALEM (1669-1707), CONFRONTS THE CHALLENGES OF MODERNITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Christopher George Rene IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser Theofanis G. Stavrou SEPTEMBER 2020 © Christopher G Rene, September 2020 i Acknowledgements Without the steadfast support of my teachers, family and friends this dissertation would not have been possible, and I am pleased to have the opportunity to express my deep debt of gratitude and thank them all. I would like to thank the members of my dissertation committee, who together guided me through to the completion of this dissertation. My adviser Professor Theofanis G. Stavrou provided a resourceful outlet by helping me navigate through administrative channels and stay on course academically. Moreover, he fostered an inviting space for parrhesia with vigorous dialogue and intellectual tenacity on the ideas of identity, modernity, and the role of Patriarch Dositheos. It was in fact Professor Stavrou who many years ago at a Slavic conference broached the idea of an Orthodox Commonwealth that inspired other academics and myself to pursue the topic. Professor Carla Phillips impressed upon me the significance of daily life among the people of Europe during the early modern period (1450-1800). As Professor Phillips’ teaching assistant for a number of years, I witnessed lectures that animated the historical narrative and inspired students to question their own unique sense of historical continuity and discontinuities. Thank you, Professor Phillips, for such a pedagogical example. -

MEDIEVAL and EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous

MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous (French) Illuminated page from a Psalter in Latin, ca. 1200-1210 Ink, Pigments and gold on parchment 2002.15 Gilbreath-McLorn Fund This page comes from a Psalter, a bound collection of the 150 Psalms, which provided medieval readers with tools for private and communal devotions. Stylistically, this leaf resembles other manuscripts produced in Northeastern France, Paris and England during the reign of the French monarch Philip Augustus (1179-1223). The script is written in a Gothic liturgical hand, and the large illuminated initials and painted line-endings were created at the same time as the text. The Verso linear penwork in-fills and flourishes were probably added after 1250. The high quality of the decoration, together with the lavish use of gold and lapis blue, indicates that this page comes from a book made for a member of the royal court or a high- ranking cleric. (MAA 11/05) Recto MAA 6/2012 Docent Manual Volume 2 Medieval and Early Renaissance 1 MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE Anonymous (Netherlandish) Adoration of the Magi from a Book of Hours, ca. 1480 Ink, pigments and gold on parchment 2003.1 Gilbreath-McLorn Museum Fund In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a fashion developed among wealthy Europeans for lavishly illustrated Books of Hours. These manuscripts contained psalms and prayers for recitation and devotions throughout the eight canonical hours of the day. In Books of Hours devoted to the Virgin Mary, an image of The Adoration of the Magi traditionally accompanies the text for sext, to be read during the mid-afternoon. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ICONS AND SAINTS OF THE EASTERN ORTHODOX CHURCH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Alfredo Tradigo | 384 pages | 01 Sep 2006 | Getty Trust Publications | 9780892368457 | English | Santa Monica CA, United States Icons and Saints of the Eastern Orthodox Church PDF Book In the Orthodox Church "icons have always been understood as a visible gospel, as a testimony to the great things given man by God the incarnate Logos". Many religious homes in Russia have icons hanging on the wall in the krasny ugol —the "red" corner see Icon corner. Guide to Imagery Series. Samuel rated it really liked it Jun 21, It did not disappoint on this detail. Later communion will be available so that one can even utilize the sense of taste during worship. Statues in the round were avoided as being too close to the principal artistic focus of pagan cult practices, as they have continued to be with some small-scale exceptions throughout the history of Eastern Christianity. The Art of the Byzantine Empire — A Guide to Imagery 10 , Bildlexikon der Kunst 9. Parishioners do not sit primly in the pews but may walk throughout the church lighting candles, venerating icons. Modern academic art history considers that, while images may have existed earlier, the tradition can be traced back only as far as the 3rd century, and that the images which survive from Early Christian art often differ greatly from later ones. Aldershot: Ashgate. In the Orthodox Church an icon is a sacred image, a window into heaven. Purple reveals wealth, power and authority. Vladimir's Seminary Press, The stillness of the icon draws us into the quiet so that we can lay aside the cares of this world and meditate on the splendor of the next. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

Chojnacki on Fogg, 'Art of Ethiopia'

H-AfrArts Chojnacki on Fogg, 'Art of Ethiopia' Review published on Friday, June 1, 2007 Sam Fogg, ed. Art of Ethiopia. Griffith Mann. Catalogue by Arcadia Fletcher. London: Paul Holberton, 2005. 128 pp. $45.00 (paper), ISBN 978-0-9549014-6-2. Reviewed by Stanislaw Chojnacki (University of Sudbury, Canada) Published on H-AfrArts (June, 2007) Identification and Dating of Crosses and Alleged Brancaleon Works I always enjoy browsing through Sam Fogg's catalogues which feature superbly reproduced pieces of Ethiopian art. Moreover the 2005 edition by Arcadia Fletcher provides an introduction by C. Griffith Mann. The introduction was a disappointment, however. Six pages of Mann's text are more praise song than history, as he describes "a stunning array of processional crosses, illuminated manuscripts, painted wooden icons and murals" which are the "visible expression to the divine and render the sacred accessible" (p. 5). The Ethiopian processional crosses "exemplify Ethiopia's long engagement with Christianity" (p. 6), and the illuminated manuscripts "speak eloquently of the Ethiopian devotion to the sacred word and its embellishment and constitutes some of the most remarkable surviving monuments of Christian culture anywhere" (p. 7). He further elaborates that "as in other Orthodox Christian cultures, Ethiopia's veneration of the sacred likeness gave rise to a rich and varied tradition of icon painting" (p. 8). While there is nothing wrong with a praise song, he then goes on to present the somewhat debatable evolution of "artistic production in Ethiopia" which depends heavily on the one presented in Marilyn Heldman's 1993 catalogue African Zion. He does not seem aware of other possibilities which have been documented more elaborately. -

The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Contents Illustrations ix Foreword by Alfredo López Austin xvii Acknowledgments xxvii Chapter 1. Converting the Indians in Sixteenth- Century Central Mexico to Christianity 1 Arrival of the Franciscan Missionaries 5 Conversion and the Theory of “Cultural Fatigue” 18 Chapter 2. From Spiritual Conquest to Parish Administration in Colonial Central Mexico 25 Partial Survival of the Ancient Calendar 31 Life in the Indian Parishes of Colonial Central Mexico 32 Chapter 3. A Trilingual, Traditionalist Indigenous Area in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 37 Regional History 40 Three Languages with a Shared Totonac Substratum 48 v Contents Chapter 4. Introduction of Christianity in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 53 Chapter 5. Local Religious Crises in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 63 Andrés Mixcoatl 63 Juan, Cacique of Matlatlán 67 Miguel del Águila, Cacique of Xicotepec 70 Pagan Festivals in Tutotepec 71 Gregorio Juan 74 Chapter 6. The Tutotepec Otomí Rebellion, 1766–1769 81 The Facts 81 Discussion and Interpretation 98 Chapter 7. Contemporary Traditions in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 129 Worship of Tutelary Mountains 130 Shrines and Sacred Constructions 135 Chapter 8. Sacred Drums, Teponaztli, and Idols from the Sierra Norte de Puebla 147 The Huehuetl, or Vertical Drum 147 The Teponaztli, or Female Drum 154 Ancient and Recent Idols in Shrines 173 Chapter 9. Traditional Indigenous Festivities in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 179 The Ancient Festival of San Juan Techachalco at Xicotepec 179 The Annual Festivity of the Tepetzintla Totonacs 185 Memories of Annual Festivities in Other Villages 198 Conclusions 203 Chapter 10. Elements and Accessories of Traditional Native Ceremonies 213 Oblations and Accompanying Rites 213 Prayers, Singing, Music, and Dancing 217 Ritual Idols and Figurines 220 Other Ritual Accessories 225 Chapter 11. -

Religious Studies (RELS) 1

Religious Studies (RELS) 1 RELS 013 Gods, Ghosts, and Monsters RELIGIOUS STUDIES (RELS) This course seeks to be a broad introduction. It introduces students to the diversity of doctrines held and practices performed, and art RELS 002 Religions of the West produced about "the fantastic" from earliest times to the present. The This course surveys the intertwined histories of Judaism, Christianity, fantastic (the uncanny or supernatural) is a fundamental category in and Islam. We will focus on the shared stories which connect these three the scholarly study of religion, art, anthropology, and literature. This traditions, and the ways in which communities distinguished themselves course fill focus both theoretical approaches to studying supernatural in such shared spaces. We will mostly survey literature, but will also beings from a Religious Studies perspective while drawing examples address material culture and ritual practice, to seek answers to the from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, following questions: How do myths emerge? What do stories do? What Central Asian, Native American, and Afro-Caribbean sources from is the relationship between religion and myth-making? What is scripture, earliest examples to the present including mural, image, manuscript, and what is its function in creating religious communities? How do film, codex, and even comic books. It will also introduce students to communities remember and forget the past? Through which lenses and related humanistic categories of study: material and visual culture, with which tools do we define "the West"? theodicy, cosmology, shamanism, transcendentalism, soteriology, For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector eschatology, phantasmagoria, spiritualism, mysticism, theophany, and Taught by: Durmaz the historical power of rumor.