Ritual-Architectural Orientation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

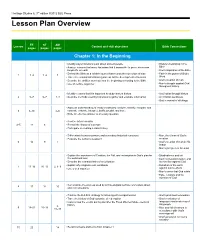

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Animals and Sacred Mountains: How Ritualized Performances Materialized State-Ideologies at Teotihuacan, Mexico

Animals and Sacred Mountains: How Ritualized Performances Materialized State-Ideologies at Teotihuacan, Mexico The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Sugiyama, Nawa. 2014. Animals and Sacred Mountains: How Citation Ritualized Performances Materialized State-Ideologies at Teotihuacan, Mexico. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Accessed April 17, 2018 4:59:24 PM EDT Citable Link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12274541 This article was downloaded from Harvard University's DASH Terms of Use repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA (Article begins on next page) $QLPDOVDQG6DFUHG0RXQWDLQV +RZ5LWXDOL]HG3HUIRUPDQFHV0DWHULDOL]HG6WDWH,GHRORJLHVDW7HRWLKXDFDQ0H[LFR $'LVVHUWDWLRQ3UHVHQWHG %\ 1DZD6XJL\DPD WR 7KH'HSDUWPHQWRI$QWKURSRORJ\ LQSDUWLDOIXOILOOPHQWRIWKHUHTXLUHPHQWV IRUWKHGHJUHHRI 'RFWRURI3KLORVRSK\ LQWKHVXEMHFWRI $QWKURSRORJ\ +DUYDUG8QLYHUVLW\ &DPEULGJH0DVVDFKXVHWWV $SULO © 2014 Nawa Sugiyama $OOULJKWVUHVHUYHG 'LVVHUWDWLRQ$GYLVRUV3URIHVVRU:LOOLDP)DVKDQG5LFKDUG0HDGRZ 1DZD6XJL\DPD $QLPDOVDQG6DFUHG0RXQWDLQV +RZ5LWXDOL]HG3HUIRUPDQFHV0DWHULDOL]HG6WDWH,GHRORJLHVDW7HRWLKXDFDQ0H[LFR $%675$&7 +XPDQVKDYHDOZD\VEHHQIDVFLQDWHGE\ZLOGFDUQLYRUHV7KLVKDVOHGWRDXQLTXHLQWHUDFWLRQZLWK WKHVHEHDVWVRQHLQZKLFKWKHVHNH\ILJXUHVSOD\HGDQLPSRUWDQWUROHDVPDLQLFRQVLQVWDWHLPSHULDOLVP -

Chapter One--Homology

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER ONE Allurement via Homologized Architecture: Monte Albán as Cosmic Mountain, Microcosm and Sacred Center (Priority I-A)................................................................129 The Layout of the Chapter: From Presumptions of “Religiosity” to Thematic Categories, Diachronic Arguments, and Critical Reflections on the “Sacredness” of Monte Albán............130 I. Monte Albán as “Sacred Space” Par Excellence: Professionalized and Popular Accolades, Affirming Assumptions and Occasional Skepticism……..……………….....…...132 II. Monte Albán as Sacred Space and Cosmic Mountain: A Synchronic View..............................141 A. Monte Albán as Heterogeneous Space and Hierophany: Discovered and/or Humanly Constructed Mountains of Sustenance………………….………..…142 1. Sacred Mountains as a Cross-Cultural Phenomenon: The Intrinsic Sacrality of High Places……………………………………………....………144 2. Sacred Mountains in Mesoamerican Cosmovision and Oaxaca: Altepeme as Sources of Abundance and Conceptions of Polity........................145 a. Altépetl as a “Water Mountain” or “Hill of Sustenance”: The Existential Allure of Cosmic Mountains…………........................146 b. Altépetl as a City-State or Territorial Political Unit: The Hegemonic Utility of Cosmic Mountains……......................................153 3. Sacred Mountains at Monte Albán: Two Key Points about Hierophanies and Cosmic Mountains at the Zapotec Capital..................................................156 a. Altepeme as “Religious Symbols”: Presystematic Ontology and the -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s. -

Chapter Four—Divinity

OUTLINE OF CHAPTER FOUR The Ritual-Architectural Commemoration of Divinity: Contentious Academic Theories but Consentient Supernaturalist Conceptions (Priority II-A).............................................................485 • The Driving Questions: Characteristically Mesoamerican and/or Uniquely Oaxacan Ideas about Supernatural Entities and Life Forces…………..…………...........…….487 • A Two-Block Agenda: The History of Ideas about, then the Ritual-Architectural Expression of, Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity……………………......….....……...489 I. The History of Ideas about Ancient Zapotec Conceptions of Divinity: Phenomenological versus Social Scientific Approaches to Other Peoples’ God(s)………………....……………495 A. Competing and Complementary Conceptions of Ancient Zapotec Religion: Many Gods, One God and/or No Gods……………………………….....……………500 1. Ancient Oaxacan Polytheism: Greco-Roman Analogies and the Prevailing Presumption of a Pantheon of Personal Gods..................................505 a. Conventional (and Qualified) Views of Polytheism as Belief in Many Gods: Aztec Deities Extrapolated to Oaxaca………..….......506 b. Oaxacan Polytheism Reimagined as “Multiple Experiences of the Sacred”: Ethnographer Miguel Bartolomé’s Contribution……...........514 2. Ancient Oaxacan Monotheism, Monolatry and/or Monistic-Pantheism: Diverse Arguments for Belief in a Supreme Being or Principle……….....…..517 a. Christianity-Derived Pre-Columbian Monotheism: Faith-Based Posits of Quetzalcoatl as Saint Thomas, Apostle of Jesus………........518 b. “Primitive Monotheism,” -

The Christianization of the Nahua and Totonac in the Sierra Norte De

Contents Illustrations ix Foreword by Alfredo López Austin xvii Acknowledgments xxvii Chapter 1. Converting the Indians in Sixteenth- Century Central Mexico to Christianity 1 Arrival of the Franciscan Missionaries 5 Conversion and the Theory of “Cultural Fatigue” 18 Chapter 2. From Spiritual Conquest to Parish Administration in Colonial Central Mexico 25 Partial Survival of the Ancient Calendar 31 Life in the Indian Parishes of Colonial Central Mexico 32 Chapter 3. A Trilingual, Traditionalist Indigenous Area in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 37 Regional History 40 Three Languages with a Shared Totonac Substratum 48 v Contents Chapter 4. Introduction of Christianity in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 53 Chapter 5. Local Religious Crises in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries 63 Andrés Mixcoatl 63 Juan, Cacique of Matlatlán 67 Miguel del Águila, Cacique of Xicotepec 70 Pagan Festivals in Tutotepec 71 Gregorio Juan 74 Chapter 6. The Tutotepec Otomí Rebellion, 1766–1769 81 The Facts 81 Discussion and Interpretation 98 Chapter 7. Contemporary Traditions in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 129 Worship of Tutelary Mountains 130 Shrines and Sacred Constructions 135 Chapter 8. Sacred Drums, Teponaztli, and Idols from the Sierra Norte de Puebla 147 The Huehuetl, or Vertical Drum 147 The Teponaztli, or Female Drum 154 Ancient and Recent Idols in Shrines 173 Chapter 9. Traditional Indigenous Festivities in the Sierra Norte de Puebla 179 The Ancient Festival of San Juan Techachalco at Xicotepec 179 The Annual Festivity of the Tepetzintla Totonacs 185 Memories of Annual Festivities in Other Villages 198 Conclusions 203 Chapter 10. Elements and Accessories of Traditional Native Ceremonies 213 Oblations and Accompanying Rites 213 Prayers, Singing, Music, and Dancing 217 Ritual Idols and Figurines 220 Other Ritual Accessories 225 Chapter 11. -

Religious Studies (RELS) 1

Religious Studies (RELS) 1 RELS 013 Gods, Ghosts, and Monsters RELIGIOUS STUDIES (RELS) This course seeks to be a broad introduction. It introduces students to the diversity of doctrines held and practices performed, and art RELS 002 Religions of the West produced about "the fantastic" from earliest times to the present. The This course surveys the intertwined histories of Judaism, Christianity, fantastic (the uncanny or supernatural) is a fundamental category in and Islam. We will focus on the shared stories which connect these three the scholarly study of religion, art, anthropology, and literature. This traditions, and the ways in which communities distinguished themselves course fill focus both theoretical approaches to studying supernatural in such shared spaces. We will mostly survey literature, but will also beings from a Religious Studies perspective while drawing examples address material culture and ritual practice, to seek answers to the from Buddhist, Shinto, Christian, Hindu, Jain, Zoroastrian, Egyptian, following questions: How do myths emerge? What do stories do? What Central Asian, Native American, and Afro-Caribbean sources from is the relationship between religion and myth-making? What is scripture, earliest examples to the present including mural, image, manuscript, and what is its function in creating religious communities? How do film, codex, and even comic books. It will also introduce students to communities remember and forget the past? Through which lenses and related humanistic categories of study: material and visual culture, with which tools do we define "the West"? theodicy, cosmology, shamanism, transcendentalism, soteriology, For BA Students: History and Tradition Sector eschatology, phantasmagoria, spiritualism, mysticism, theophany, and Taught by: Durmaz the historical power of rumor. -

Ritual-Architectural Orientation

OUTLINE OF THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION Reconceptualizing Religion: Orientation and/or Cosmovision as That Which Matters Most.……...…….1 I. Dilemmas in Defining Religion: The Non-Option of Neutrality and the Selection of a Heuristic Stipulation Suitable to Our Present Purposes……………......................………...3 A. The Extreme Imbalance of Oaxacanist Studies: A Wealth of Religion- Related Data but a Paucity of Theorizing about Religion……………………….....……7 B. The Contingency of Every Definition of Religion: Methodological Clarity and Self-Consciousness about what Qualifies as “Religious” ……………......………11 C. Embracing One Working Stipulation of Religion: Thomas Carlyle on “That Which Matters Most” to a Person or People…………………...….....….........…14 D. Avoiding Two Untoward Presuppositions about Religion: Not a Coherent System of Beliefs and Not an Apolitical Sphere of Culture…………….....…...…..…..16 E. The Agenda of the Introduction: Paired Appeals to Comparative Religionists on Orientation and Mesoamericanists on Cosmovision…………………….....……….23 II. Reconceptualizing Religion: Intersections between the Cross-Culturally Comparative History of Religions and Mesoamerican Studies .......................................................................26 A. Religionists’ Reconceptualizations: Religion as Orientation and a Study of Religion Based Foremost on Material (Non-Literary) Evidence................................26 1. Mircea Eliade’s Point of Departure: “Being Religious” and Finding Orientation as Constitutive of the Human Condition…….......………………...27 -

1 ANTHROPOLOGY 140G – MESOAMERICAN COSMOVISION and CULTURE GFS 106, M/W 2:00-3:20 Dr. Kenneth E. Seligson TA: Dr. Kirby Farah

Anth 140 Course Syllabus Fall 2018 ANTHROPOLOGY 140g – MESOAMERICAN COSMOVISION AND CULTURE GFS 106, M/W 2:00-3:20 Dr. Kenneth E. Seligson TA: Dr. Kirby Farah Phone: (213) 740-1902 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Office Hours: M 12-2 Office Hours: M/W 12-1 Office: THH B8 Office: HNB (Hedco) 29A Course Description Anthropology 140g provides a general introduction to the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica and the ways in which they are studied. The emphasis in the course is on understanding how different societies manifested a core set of beliefs shared by all Mesoamerican civilizations while at the same time maintaining local cultural identities. The course addresses changes in Mesoamerica both spatially and temporally from the Archaic Period through the Spanish Conquest. Throughout the course, there will be a general emphasis on broad themes such as religion, identity, and political organization and how these themes are detected and presented by scholars of Mesoamerican civilizations. Recommended Preparation An introductory archaeology course would be helpful, but is not required. The aims of this course are threefold: 1) To introduce you to the major cultures and time periods of Mesoamerica. 2) To help you critically examine the different ways in which scholars interpret the past. 3) To encourage you to think openly about Mesoamerican civilizations and to create your own arguments about the past. This last aim is a critical component of the course and there will be many opportunities to demonstrate this ability. 1 Anth 140 Course Syllabus Fall 2018 Introduction, Objectives, and Outcomes Mesoamerica is one of the great culture areas of the ancient and modern world. -

Shamans and Symbols

SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS SHAMANS AND SYMBOLS PREHISTORY OF SEMIOTICS IN ROCK ART Mihály Hoppál International Society for Shamanistic Research Budapest 2013 Cover picture: Shaman with helping spirits Mohsogollokh khaya, Yakutia (XV–XVIII. A.D. ex: Okladnikov, A. P. 1949. Page numbers in a sun symbol ex: Devlet 1998: 176. Aldan rock site ISBN 978-963-567-054-3 © Mihály Hoppál, 2013 Published by International Society for Shamanistic Research All rights reserved Printed by Robinco (Budapest) Hungary Director: Péter Kecskeméthy CONTENTS List of Figures IX Acknowledgments XIV Preface XV Part I From the Labyrinth of Studies 1. Studies on Rock Art and/or Petroglyphs 1 2. A Short Review of Growing Criticism 28 Part II Shamans, Symbols and Semantics 1. Introduction on the Beginning of Shamanism 39 2. Distinctive Features of Early Shamans (in Siberia) 44 3. Semiotic Method in the Analysis of Rock “Art” 51 4. More on Signs and Symbols of Ancient Time 63 5. How to Mean by Pictures? 68 6. Initiation Rituals in Hunting Communities 78 7. On Shamanic Origin of Healing and Music 82 8. Visual Representations of Cognitive Evolution and Community Rituals 92 Bibliography and Further Readings 99 V To my Dito, Bobo, Dodo and to my grandsons Ákos, Magor, Ábel, Benedek, Marcell VII LIST OF FIGURES Part I I.1.1. Ritual scenes. Sagan Zhaba (Baykal Region, Baykal Region – Okladnikov 1974: a = Tabl. 7; b = Tabl. 16; c = Tabl. 17; d = Tabl. 19. I.1.2. From the “Guide Map” of Petroglyhs and Sites in the Amur Basin. – ex: Okladnikov 1981. No. 12. = Sikachi – Alyan rock site.