The Anthropology of Mesoamerican Caves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Reassessment on the Lithic Artefacts from the Earliest Human Occupations at Puente Rock Shelter, Ayacucho Valley, Peru

Archaeological Discovery, 2021, 9, 91-112 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ad ISSN Online: 2331-1967 ISSN Print: 2331-1959 A Reassessment on the Lithic Artefacts from the Earliest Human Occupations at Puente Rock Shelter, Ayacucho Valley, Peru Juan Yataco Capcha1, Hugo G. Nami2, Wilmer Huiza1 1Archaeological and Anthropological of San Marcos University Museum, Lima, Perú 2Department of Geological Sciences, Laboratory of Geophysics “Daniel A. Valencio”, CONICET-IGEBA, FCEN, UBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina How to cite this paper: Capcha, J. Y., Abstract Nami, H. G., & Huiza, W. (2021). A Reas- sessment on the Lithic Artefacts from the Richard “Scotty” MacNeish, between 1969 and 1972, led an international Earliest Human Occupations at Puente Rock team of archaeologists on the Ayacucho Archaeological-Botanical—Project in Shelter, Ayacucho Valley, Peru. Archaeo- the south-central highlands of Peru. Among several important archaeological logical Discovery, 9, 91-112. https://doi.org/10.4236/ad.2021.92005 sites identified there, MacNeish and his team excavated the Puente rock shel- ter. As a part of an ongoing research program aimed to reassess the lithic re- Received: February 14, 2021 mains from this endeavor, we re-studied a sample by making diverse kinds of Accepted: March 22, 2021 morpho-technological analysis. The remains studied come from the lower Published: March 25, 2021 strata at Puente, where a radiocarbon assay from layer XIIA yielded a cali- Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and brated date of 10,190 to 9555 years BP that the present study identifies, vari- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. ous activities were carried out at the site, mainly related to manufacturing and This work is licensed under the Creative repairing unifacial and bifacial tools. -

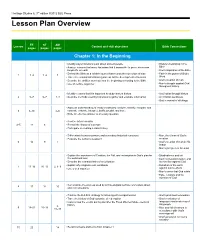

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Hironymousm16499.Pdf

Copyright by Michael Owen Hironymous 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Michael Owen Hironymous certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio Committee: Julia E. Guernsey, Supervisor Frank K. Reilly, III, Co-Supervisor Brian M. Stross David S. Stuart John M. D. Pohl Santa María Ixcatlan, Oaxaca: From Colonial Cacicazgo to Modern Municipio by Michael Owen Hironymous, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2007 Dedication Al pueblo de Santa Maria Ixcatlan. Acknowledgements This dissertation project has benefited from the kind and generous assistance of many individuals. I would like to express my gratitude to the people of Santa María Ixcatlan for their warm reception and continued friendship. The families of Jovito Jímenez and Magdaleno Guzmán graciously welcomed me into their homes during my visits in the community and provided for my needs. I would also like to recognize Gonzalo Guzmán, Isabel Valdivia, and Gilberto Gil, who shared their memories and stories of years past. The successful completion of this dissertation is due to the encouragement and patience of those who served on my committee. I owe a debt of gratitude to Nancy Troike, who introduced me to Oaxaca, and Linda Schele, who allowed me to pursue my interests. I appreciate the financial support that was extended by the Teresa Lozano Long Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of Texas and FAMSI. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America

206 Evolutionary Anthropology ARTICLES The Late Pleistocene Cultures of South America TOM D. DILLEHAY Important to an understanding of the first peopling of any continent is an Between 11,000 and 10,000 years understanding of human dispersion and adaptation and their archeological signa- ago, South America also witnessed tures. Until recently, the earliest archeological record of South America was viewed many of the changes seen as being uncritically as a uniform and unilinear development involving the intrusion of North typical of the Pleistocene period in American people who brought a founding cultural heritage, the fluted Clovis stone other parts of the world.5,9–11 These tool technology, and a big-game hunting tradition to the southern hemisphere changes include the use of coastal between 11,000 and 10,000 years ago.1–3 Biases in the history of research and the resources and related developments in agendas pursued in the archeology of the first Americans have played a major part marine technology, demographic con- in forming this perspective.4–6 centration in major river basins, and Despite enthusiastic acceptance of the Clovis model by a vast majority of the practice of modifying plant and 6–11 archeologists, several South American specialists have rejected it. They contend animal distributions. Others occur that the presence of archeological sites in Tierra del Fuego and other regions by at later, between 10,000 and 9,000 years least 11,000 to 10,500 years ago was simply insufficient time for even the fastest ago, and include most of the changes migration of North Americans to reach within only a few hundred years. -

Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION the Maya Empire, Centered in The

Unit III – Lesson 1 MAYAN CIVILIZATION The Maya Empire, centered in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala, reached the peak of its power and influence around the sixth century A.D. The Maya excelled at agriculture, pottery, hieroglyph writing, calendar-making and mathematics. The Maya civilization was one of the most dominant indigenous societies of Mesoamerica. The earliest Maya settlements date to around 1800 B.C., or the beginning of what is called the Preclassic or Formative Period. The earliest Maya were agricultural, growing crops such as corn (maize), beans, squash and cassava (manioc). During the Middle Preclassic Period, which lasted until about 300 B.C., Maya farmers began to expand their presence both in the highland and lowland regions. The Middle Preclassic Period also saw the rise of the first major Mesoamerican civilization, the Olmecs. Like other Mesamerican peoples, the Maya derived a number of religious and cultural traits. The Maya were deeply religious, and worshiped various gods related to nature, including the gods of the sun, the moon, rain and corn. At the top of Maya society were the kings, or (holy lords), who claimed to be related to gods and followed a hereditary succession. They were thought to serve as mediators between the gods and people on earth, and performed the elaborate religious ceremonies and rituals so important to the Maya culture. Maya Arts and Culture :- The Classic Maya built many of their temples and palaces in a stepped pyramid shape, decorating them with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions. These structures have earned the Maya their reputation as the great artists of ` Mesoamerica. -

Poster/Flyer

25th-26th September 2013 27th-28th September 2013 International conference 2nd Forum on Iconography and workshop in Mesoamerica THE COIXTLAHUACA VALLEY, OAXACA, MEXICO TIME AND SPACE IN MESOAMERICA Current Research in Archaeology, History, Ethnology and Document Analysis Meeting Place Ethnologisches Museum - Staatliche Museen Berlin│Dahlem Museen │Lansstraße 8 │14195 Berlin U-Bhf. Dahlem Dorf (U3) │Bus M11, X 83, 101, 110 Contact Prof. Dr. Viola König │Director Ethnologisches - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin │Arnimallee 27 │ 14195 Berlin Phone: +49 030 8301-226/-231 │Fax: +49 030 8301-506 │ [email protected] │ www.smb.museum/em [email protected] International conference and workshop. September 25 and 26, 2013 techniques. His unusual background in archaeology, art history, and Ethnologisches Museum, Lansstraße 8, 14195 Berlin media production have taken him from museum exhibition design and development with the Walt Disney Company's Department of Cultural THE COIXTLAHUACA VALLEY, OAXACA, MEXICO Affairs to Princeton University where he served as the first Peter Jay Current Research in Archaeology, History, Ethnology and Sharp Curator and Lecturer in the Art of the Ancient Americas. Most Document Analysis recently, John Pohl curated the exhibition “The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire” for the Getty Villa Museum and is currently developing Wednesday, September 25, 2013 “Children of the Plumed Serpent: The Legacy of Quetzalcoatl in Ancient Mexico” for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Dallas Museum 7.30pm of Art. He is the author of the FAMSI website 'John Pohl's Mesoamerica', Foyer 1st floor and was co-author of Kevin Costner's '500 Nations'. -

Assessing Relationships Between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology Via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling William E

Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco-cultural niche modeling William E. Banks To cite this version: William E. Banks. Assessing relationships between human adaptive responses and ecology via eco- cultural niche modeling. Archaeology and Prehistory. Universite Bordeaux 1, 2013. hal-01840898 HAL Id: hal-01840898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01840898 Submitted on 11 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Thèse d'Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Université de Bordeaux 1 William E. BANKS UMR 5199 PACEA – De la Préhistoire à l'Actuel : Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie Assessing Relationships between Human Adaptive Responses and Ecology via Eco-Cultural Niche Modeling Soutenue le 14 novembre 2013 devant un jury composé de: Michel CRUCIFIX, Chargé de Cours à l'Université catholique de Louvain, Belgique Francesco D'ERRICO, Directeur de Recherche au CRNS, Talence Jacques JAUBERT, Professeur à l'Université de Bordeaux 1, Talence Rémy PETIT, Directeur de Recherche à l'INRA, Cestas Pierre SEPULCHRE, Chargé de Recherche au CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette Jean-Denis VIGNE, Directeur de Recherche au CNRS, Paris Table of Contents Summary of Past Research Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

The Political Appropriation of Caves in the Upper Belize Valley

APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF REQUIREMENTS FOR DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LOS ANGELES BY Michael J. Mirro Candidate Anthropology Field of Concentration TITLE: The Political Appropriation of Caves in the Upper Belize Valley APPROVED: Dr. James E. Brady Faculty Member Signature Dr. Patricia Martz Faculty Member Signature Dr. Norman Klein Faculty Member Signature Dr. ChorSwang Ngin Department Chairperson Signature DATE___________________ THE POLITICAL APPROPRIATION OF CAVES IN THE UPPER BELIZE VALLEY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology California State University, Los Angeles In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Michael J. Mirro December 2007 © 2007 Michael J. Mirro ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Jaime Awe, of the Department of Archaeology in Belmopan, Belize for providing me with the research opportunities in Belize, and specifically, allowing me to co-direct research at Barton Creek Cave. Thank you Jaime for sending Vanessa and I to Actun Tunichil Muknal in the summer of 1996; that one trip changed my life forever. Thank you Dr. James Brady for guiding me through the process of completing the thesis and for you endless patience over the last four years. I appreciate all the time and effort above and beyond the call of duty that you invested in assisting me. I would specifically like to thank Reiko Ishihara and Christophe Helmke for teaching me the ins-and-outs of Maya ceramics and spending countless hours with me classifying sherds. Without your help, I would never have had enough data to write this thesis. -

Duccio Bonavia Berber (March 27, 1935-August 4, 2012) Ramiro Matos Mendieta Smithsonian Institution, [email protected]

Andean Past Volume 11 Article 9 12-15-2013 Duccio Bonavia Berber (March 27, 1935-August 4, 2012) Ramiro Matos Mendieta Smithsonian Institution, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past Recommended Citation Matos Mendieta, Ramiro (2013) "Duccio Bonavia Berber (March 27, 1935-August 4, 2012)," Andean Past: Vol. 11 , Article 9. Available at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/andean_past/vol11/iss1/9 This Obituaries is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Andean Past by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DUCCIO BONAVIA BERBER (MARCH 27, 1935-AUGUST 4, 2012) Ramiro Matos Mendieta National Museum of the American Indian Smithsonian Institution Portrait of Duccio Bonavia Berber courtesy of the Bonavia family Duccio Bonavia Berber died at dawn, at the I can imagine that Duccio had a premoni- age of seventy-seven, on Saturday, August 4, tion of his death. During conversations in June, 2012, in Ascope, Department of Trujillo, Peru. less than two months before he died, uncharac- Death surprised him while he was carrying out teristically, he emphasized his worries about his the last phase of his field-work at Huaca Prieta, life, and the serious problems that Tom would Magdalena de Cao, on Peru’s north coast. His face if there were a death in the field, as well as research project at the emblematic site was co- those of his daughter and son, because of the directed with Tom Dillehay of Vanderbilt Uni- distance, and even the effect such an event versity. -

Ancient Civilisation’ Through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures

Structuring The Notion of ‘Ancient Civilisation’ through Displays: Semantic Research on Early to Mid-Nineteenth Century British and American Exhibitions of Mesoamerican Cultures Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez Institute of Archaeology U C L Thesis forPh.D. in Archaeology 2011 1 I, Emma Isabel Medina Gonzalez, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis Signature 2 This thesis is dedicated to my grandparents Emma and Andrés, Dolores and Concepción: their love has borne fruit Esta tesis está dedicada a mis abuelos Emma y Andrés, Dolores y Concepción: su amor ha dado fruto Al ‘Pipila’ porque él supo lo que es cargar lápidas To ‘Pipila’ since he knew the burden of carrying big stones 3 ABSTRACT This research focuses on studying the representation of the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ in displays produced in Britain and the United States during the early to mid-nineteenth century, a period that some consider the beginning of scientific archaeology. The study is based on new theoretical ground, the Semantic Structural Model, which proposes that the function of an exhibition is the loading and unloading of an intelligible ‘system of ideas’, a process that allows the transaction of complex notions between the producer of the exhibit and its viewers. Based on semantic research, this investigation seeks to evaluate how the notion of ‘ancient civilisation’ was structured, articulated and transmitted through exhibition practices. To fulfil this aim, I first examine the way in which ideas about ‘ancientness’ and ‘cultural complexity’ were formulated in Western literature before the last third of the 1800s.