Epic Stories That Bridge the Ancient and Present Worlds in Tajikistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

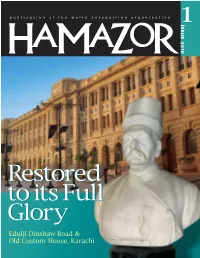

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Comparison of Arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh Based on the Ancient Story of Bahmannameh

Propósitos y Representaciones May. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(3), e1092 ISSN 2307-7999 Current context of education and psychology in Europe and Asia e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 RESEARCH NOTES Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Comparación de la arrogancia en Shahnameh y Bahmannameh basada en la antigua historia de Bahmannameh Zohreh Amiri PhD student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Reza Ashrafzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Mohammad Shah Badiezadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Received 07-08-20 Revised 08-10-20 Accepted 09-02-20 On line 03-06-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Amiri, Z., Ashrafzadeh, R., & Shah Badiezadeh, M. (2021). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE3), e1092. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. Este artículo se distribuye bajo licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Summary One of the most important aspects of the struggle of warriors and warriors in epic works is the arrogance that is called by the comrades before the start of the hand-to-hand battle. It is accompanied by pride in ancestry, race, and ridicule. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected]; -

Why Was the Story of Arash-I Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?” Iran Nameh, 29:2 (Summer 2014), 42-63

Saghi Gazerani, “Why Was the Story of Arash-i Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?” Iran Nameh, 29:2 (Summer 2014), 42-63. Why Was the Story of Arash-i Kamangir Excluded from the Shahnameh?* Saghi Gazerani Independent Scholar In contemporary Iranian culture, the legendary figure of Arash-i Kamangir, or Arash the Archer, is known and celebrated as the national hero par excellence. After all, he is willing to lay down his life by infusing his arrow with his life force in order to restore territories usurped by Iran’s enemy. As the legend goes, he does so in order to have the arrow move to the farthest point possible for the stretch of land over which the arrow flies shall be included in Iranshahr proper. The story without a doubt was popular for many centuries, but during the various upheavals of the twentieth century, the story of Arash the Archer was invoked, and in the hands of artists with various political leanings his figure was imbued with layers reflecting the respective artist’s ideological presuppositions.1 The most famous of modern renditions of Arash’s legend is Siavash Kasra’i’s narrative poem named after its protagonist. An excerpt of Kasra’i’s rendition of Arash’s story *For further discussion of this issue please see my ture,” www.iranicaonline.org (accessed March 3, forthcoming work, On the Margins of Historiog- 2014). Arash continues to make his appearance; raphy: The Sistani Cycle of Epics and Iran’s Na- for a recent operatic performance of the legend, tional History (Leiden: Brill, 2014). -

Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian Epic)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Revista Amazonia Investiga Florencia, Colombia, Vol. 6 Núm. 10 /enero-junio 2017/ 151 Artículo de investigación Interpretation and analysis of epic thinking in Iran and Scandinavia emphasizing the story of Esfandiar (Shahnameh) and Balder (Scandinavian epic) Interpretación y análisis del pensamiento épico en Irán y Escandinavia enfatizando la historia de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) y Balder (épica escandinava) Interpretação e análise do pensamento épico no Irã e na Escandinávia enfatizando a história de Esfandiar (Shahnameh) e Balder (épico escandinavo) Recibido: 9 de abril de 2017. Aceptado: 30 de mayo de 2017 Escrito por: Shahrbanoo Ganjeh39 Alimohammad Moazzeni2* Tofigh Sobhani3 Mohammed Reza Shad Manamen4 Abstract Resumen Apart from the impact and impact of the two Además del impacto y el impacto de las dos lands, a way can be opened in There is a special tierras, se puede abrir una vía en Hay un tema subject that there is a shared point of content in especial en el que hay un punto de contenido it and it is a source of analogy A topic, a tendency compartido y es una fuente de analogía Un tema, and a special content of common interest in two una tendencia y un contenido especial de común different territories. Question one of the most interés en dos territorios diferentes. Pregunta important and frequent points in the history of uno de los puntos más importantes y frecuentes the literatures and beliefs of different lands It is en la historia de las literaturas y creencias de on the side of history and on the side of human diferentes países. -

Why Should Anyone Be Familiar with Persian Literature?

Annals of Language and Literature Volume 4, Issue 1, 2020, PP 11-18 ISSN 2637-5869 Why should anyone be Familiar with Persian Literature? Shabnam Khoshnood1, Dr. Ali reza Salehi2*, Dr. Ali reza Ghooche zadeh2 1M.A student, Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran *Corresponding Author: Dr. Ali reza Salehi, Persian language and literature department, Electronic branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Literature is a tool for conveying concepts, thoughts, emotions and feelings to others that has always played an important and undeniable role in human life. Literature encompasses all aspects of human life as in love and affection, friendship and loyalty, self-sacrifice, justice and cruelty, manhood and humanity, are concepts that have been emphasized in various forms in the literature of different nations of the world. Poets and writers have endeavored to be heretics in the form of words and sentences and to promote these concepts and ideas to their community. Literature is still one of the most important identifiers of nations and ethnicities that no other factor has been able to capture. As a rich treasure trove of informative and educational material, Persian literature has played an important role in the development and reinforcement of social ideas and values in society, which this mission continues to do best. In this article, we attempt to explain the status of Persian literature and its importance. Keywords: language, literature, human, life, religion, culture. INTRODUCTION possible to educate without using the humanities elite. -

Cattle and Its Mythical-Epic Themes in Shahnameh, Garshasbnameh, Koushnameh, Borznameh, Bahmannameh and Banogoshasbnameh

Propósitos y Representaciones Jan. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(1), e871 ISSN 2307-7999 Special Number: Educational practices and teacher training e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.871 CONFERENCES Cattle and its mythical-epic themes in Shahnameh, Garshasbnameh, Koushnameh, Borznameh, Bahmannameh and Banogoshasbnameh El ganado y sus temas mítico-épicos en Shahnameh, Garshasbnameh, Koushnameh, Borznameh, Bahmannameh y Banogoshasbnameh Nasrin Sharifzad PhD Student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Mohammad Shah Badizadeh Department of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Reza Ashrafzadeh Department of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Received 10-10-20 Revised 11-12-20 Accepted 01-13-21 On line 01-14-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Sharifzad, N., Shah Badizadeh, M., & Ashrafzadeh, R. (2021). Investigation and analysis of color pragmatics in Beyghami DarabNameh. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9 (SPE1), e871. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.871 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2020. This article is distributed under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Cattle and its mythical-epic themes in Shahnameh, Garshasbnameh, Koushnameh, Borznameh, Bahmannameh and Banogoshasbnameh Summary In Shahnameh and other epic poems, which reflect the myths, the life of primitive and ancient Iranian societies, animals and other animals are of great importance and go beyond their normal features and status. Myths that are truths of the thoughts and ideas of the first people, which are mixed with different stories and are expressed symbolically and cryptically. -

Leopard and Its Mythological-Epic Motifs in Shahnameh and Four Other Epic Works (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh and Borzunameh)

Propósitos y Representaciones Jan. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(1), e891 ISSN 2307-7999 Special Number: Educational practices and teacher training e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.891 RESEARCH ARTICLES Leopard and its mythological-epic motifs in Shahnameh and four other epic works (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh and Borzunameh) Leopardo y sus motivos mitológicos-épicos en Shahnameh y otras cuatro obras épicas (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh y Borzunameh) Nasrin Sharifizad PhD student in Persian Language and Literature (pure), Mashhad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad, Iran ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7171-7103 Mohammad Shah Badi’zadeh Assistant Professor, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Mashhad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad, Iran ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1555-3877 Reza Ashrafzadeh Professor, Department of Persian Language and Literature, Mashhad Branch, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad, Iran ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5392-9273 Received 02-08-20 Revised 04-10-20 Accepted 01-11-21 On line 01-18-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Sharifizad, N., Badizadeh, M., & Ashrafzadeh, R. (2021). Leopard and its mythological-epic motifs in Shahnameh and four other epic works (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh and Borzunameh). Propósitos y Representaciones, 9 (SPE1), e891. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.891 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2020. This article is distributed under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Leopard and its mythological-epic motifs in Shahnameh and four other epic works (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh and Borzunameh) Summary In Shahnameh and other epic poems where the reflection of myths is the life of primitive and ancient Iranian communities, animals and other creatures are of great importance and go beyond their normal features and position. -

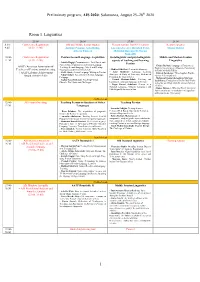

Preliminary Program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28Th 2020

Preliminary program, AIS 2020: Salamanca, August 25–28th 2020 Room 1. Linguistics 25.08 26.08 27.08 28.08 8:30- Conference Registration Old and Middle Iranian studies Plenary session: Iran-EU relations Keynote speaker 9:45 (8:30–12:00) Antonio Panaino, Götz König, Luciano Zaccara, Rouzbeh Parsi, Maziar Bahari Alberto Cantera Mehrdad Boroujerdi, Narges Bajaoghli 10:00- Conference Registration Persian Second Language Acquisition Sociolinguistic and psycholinguistic Middle and Modern Iranian 11:30 (8:30–12:00) aspects of teaching and learning Linguistics - Latifeh Hagigi: Communicative, Task-Based, and Persian Content-Based Approaches to Persian Language - Chiara Barbati: Language of Paratexts as AATP (American Association of Teaching: Second Language, Mixed and Heritage Tool for Investigating a Monastic Community - Mahbod Ghaffari: Persian Interlanguage Teachers of Persian) annual meeting Classrooms at the University Level in Early Medieval Turfan - Azita Mokhtari: Language Learning + AATP Lifetime Achievement - Ali R. Abasi: Second Language Writing in Persian - Zohreh Zarshenas: Three Sogdian Words ( Strategies: A Study of University Students of (m and ryżי k .kי rγsי β יי Nahal Akbari: Assessment in Persian Language - Award (10:00–13:00) Persian in the United States Pedagogy - Mahmoud Jaafari-Dehaghi & Maryam - Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi: Teaching and - Asghar Seyed-Ghorab: Teaching Persian Izadi Parsa: Evaluation of the Prefixed Verbs learning the formulaic language in Persian Ghazals: The Merits and Challenges in the Ma’ani Kitab Allah Ta’ala -

Parsi) Hill - Jimmy Suratia 28 Finding ‘Saosha, Tying Kusti’ in Sogdiana

Become a member online with a simple click or through the following individuals: UK residents and other countries please send completed application form and cheque payable in Sterling to WZO, London to: Mrs Khurshid Kapadia, 217 Pickhurst Rise, West Wickham, Kent BR4 0AQ, UK. USA residents - application form and cheque payable in US Dollars as “The World Zoroastrian Organisation (US Region)” to: Mr Kayomarsh Mehta, 6943 Fieldstone Drive, Burr Ridge, Illinois IL60527-5295, USA. Canadian residents - application form and cheque payable in Canadian Dollars as “ZSO” and marked WZO fees to: The Treasurer, ZSO, 3590 Bayview Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M2M 356, Canada. Ph: (416) 733 4586. New Zealand residents - application form with your cheque payable in NZ Dollars as “World Zoroastrian Organisation, to: Mr Darius Mistry, 134A Paritai Drive, Orakei, Auckland, New Zealand HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2014 COVER The four images used are on pages 71 & 72 where full credit is given. PHOTOGRAPHS Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in C o n t e n t s the magazine or as mentioned. 04 Abtin Sassanfar WZO WEBSITE 05 Report from the Chairman, WZO 07 European Interfaith Youth Network - benafsha engineer www.w-z-o.org 10 “Marriage nu spot Fixing” - pauruchisty kadodwala 11 Be Good - Sing Ashem Vohu - khosro mehrfar 13 Structural Limits on Gatha Studies - dinyar mistry 16 A Gathic View of Zoroastrianism & Ethical Life - review, soli dastur 19 Farohar/Fravahar Motif. Parts I & II - k.e.eduljee 25 Commemoration of the Zoroastrian (Parsi) Hill - jimmy suratia 28 Finding ‘Saosha, tying Kusti’ in Sogdiana. Part I - kersi shroff 32 The Cyrus Cylinder at the MET - behroze clubwalla 36 The Cyrus Cylinder’s visit to SF - nazneen spliedt 38 Four Funerals & a Concert for ‘Peace’ - dilnaz boga 40 Dr Murad Lala scales Mt Everest - beyniaz edulji 44 Outstanding Young Houstonian - magdalena rustomji 46 The Jam e Janbakhtegan Games - taj gohar kuchaki 48 G.K. -

Journal of American Science, 2011;7(10)

Journal of American Science, 2011;7(10) http://www.americanscience.org Symbolic world of dream in Kushnameh Nahid Yousefzadeh Department of Persian Literature, Sajad University of Iran, Mashhad, Iran [email protected] Abstract: In this study, dream symbols and their effect on opinion of the poet are reviewed, and difference between the application of this element in Shahnameh and Kushnameh is expressed. The dreams are one of several attractiveness factors of Iranshah stories in Kushnamh. He expresses beautiful and mysterious stories and legends, and in addition to respecting national and cultural values and figures, secret of many complexities are revealed to us in the form of a dream. His mysterious dreams have also features of Ahormazda dreams. In addition, they carry messages that contain their probable problems as well, which are symbolic and the truth is hidden in secrets. Iranshah has tried to reflect the hidden dimensions of his story characters and heroes in their dreams, and to create images with elements of dream that never happen in reality. He also tries to warn his readers and those who suffer from negligence and awaken and bring them to the world of conscious. [Nahid Yousefzadeh. Symbolic world of dream in Kushnameh. Journal of American Science 2011;7(10):84-90]. (ISSN: 1545-1003). http://www.americanscience.org. Keywords: Sleep; Dream; Ahourai dream; Decryption; Kamdad mysterious; Abtin 1. Introduction part of the book includes verses as praise of This article reviews sleep and dream knowledge. Then God is worshiped and praised. symbols in the Kushnameh epic and its effects on thought of the story composer, who is Iranshah Ibn 2. -

NAMC Seminar - Zarathushtra and the Legendary Dynasties Page 1 of 42

Zarathushtra and the legendary dynasties by Ervads Soli Dastur and Jehan Bagli Saturday May 19, 2007 Pishdadian Dynasty The history of Persia and that of the Zarathushtrian Faith is deeply intertwined. The story begins with a legendary House of monarchs known as Pishdadian. The word Pishdad is a later modification of the ancient word Paradhata meaning the ancient lawgiver. The founder of this dynasty was Kayomerz (in ancient Persian) or Gayo-maretan (in Avestan) or Gayomard (in Pahlavi). These words essentially refer to the first mortal man, Gayo- meaning life and – maretan refers to mortal human. In principle the dynasty is believed to have started with the inception of the creation of the mortal man. Kayomerz with his two successors Hushang and Tahmurus is believed to have laid the foundation of cultural civilization in Iran. In the prayers of Dibache for afringan we recite az Gayomard anda Sosyos. Here we remember the fravashis of the entire mankind starting with Gayomard and ending with Saoshyant. In Fravardin Yasht (13.87) where we revere the fravashi of Gayomard, we are told Ahurai Mazdai manascha gushta sasnaoscha. This means he was the first to have heard the intentions and admonitions of Ahura Mazda. It is believed that he and the creation of the good God lasted for some three thousand years, at which time there was an onslaught of evil on the good creation. This brought an end to the era of Gayomard and his life. Mythology speaks of the legendary evolution of the Rivas plant from the slain body of Gayomard and the first man Mashya and woman Mashyani sprang forth as flowers from that plant.