Zoroastrian Funeral Practices: Transition in Conduct Anton Zykov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

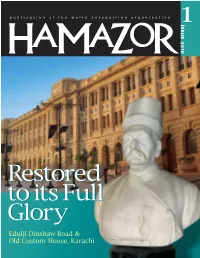

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Proposal to Encode the 'Fravahar' Symbol in Unicode

L2/15-099 2015-03-30 Proposal to Encode the ‘Fravahar’ Symbol in Unicode Anshuman Pandey Department of Linguistics University of Californa, Berkeley Berkeley, California, U.S.A. [email protected] March 30, 2015 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode a symbol associated with Zoroastrianism and the cultural legacy of Iran in Unicode. The character is proposed for inclusion in the block ‘Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs’ (U+1F300). Basic details of the character are as follows: glyph code point character name U+1F9xx FRAVAHAR The representative glyph is derived from an image available on Wikimedia Commons, which was released into the public domain: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Faravahar-Gold.svg. The actual code point will be determined if the proposal is approved. 2 Background In the proposal “Emoji Additions” (L2/14-174), authored by Mark Davis and Peter Edberg, five ‘religious symbols and structures’ among symbols of other categories were proposed for inclusion as part of the Emoji collection in Unicode. Shervin Afshar and Roozbeh Pournader proposed related symbols in “Emoji and Symbol Additions – Religious Symbols and Structures” (L2/14-235). These characters were approved for inclusion in the standard by the UTC in January 2015. No mention was made of symbols associated with Zoroastrianism, but these do exist. This proposal seeks to encode the , one of the most important and recognizable of Zoroastrian symbols. Encoding the in Unicode will enable Zoroastrians worldwide to represent a motif of their religious tradition on digital platforms on par with adherents of other religions. 1 Proposal to Encode the ‘Fravahar’ Symbol in Unicode Anshuman Pandey 3 Description The symbol proposed here is commonly known as fravahar in the Zoroastrian community in Iran and the Parsi community in India (Zoroastrians in India are commonly known as ‘Parsi’). -

Reaching the Least Reached CCBA

CENTRAL COAST BAPTIST ASSOCIATION Reaching the Least Reached What is an unreached people Where do UPGs live? What are the largest unreached and an unengaged people people groups in the Bay Area? group? It will be a surprise to some people that some large, very Nobody knows for certain yet A people group is unreached unreached people groups live in the which the largest UPGs are in the Bay when the number of evangelical United States, and even within the Area, but we do know which of them Christians is less than 2% of its geography of the Central Coast are the largest in the world. We also population (UPG). It is further called Baptist Association. They represent know some of them that are certainly unengaged (UUPG) when there is no various regions of the world such as here in large numbers, mostly in Santa church planting methodology China, India and the Middle East. Clara, Alameda, San Francisco, San consistent with evangelical faith and They are adherents of world religions Mateo and Contra Costa counties. practice under way. “A people group such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, There are more UPGs here than there is not engaged when it has been Sikhism and Jainism. can ever be paid missionaries to work merely adopted, is the object of among them. It will take ordinary focused prayer, or is part of an Christians who are willing to pray and advocacy strategy.” (IMB) work in extraordinary ways so that Today there are 6,430 unreached people from every nation, tribe, and people groups around the world. -

RTR-IV-Annual-Report

ZOROASTRIAN RETURN TO ROOTS ZOROASTRIAN RETURN TO ROOTS Welcome 3 Acknowledgements 4 About 8 Vision 8 The Fellows 9 Management Team 30 Return: 2017 Trip Summary 36 Revive: Ongoing Success 59 Donors 60 RTR Annual Report - 2017 WELCOME From 22nd December 2017 - 2nd January 2018, 25 young Zoroastrians from the diaspora made a journey to return, reconnect, and revive their Zoroastrian roots. This was the fourth trip run by the Return to Roots program and the largest in terms of group size. Started in 2012 by a small group of passionate volunteers, and supported by Parzor, the inaugural journey was held from December 2013 to January 2014 to coincide with the World Zoroastrian Congress in Bombay, India. The success of the trips is apparent not only in the transformational experiences of the participants but the overwhelming support of the community. This report will provide the details of that success and the plans for the program’s growth. We hope that after reading these pages you will feel as inspired and motivated to act as we have. Sincerely, The Zoroastrian Return to Roots Team, 2017 3 RTR Annual Report - 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As we look back on four successful trips of Return to Roots, we are reminded, now more than ever, of the countless people who have lent their support and their time to make sure that the youth on each of these trips have an unforgettable experience. All we can offer to those many volunteers and believers who have built this program is our grateful thanks and the hope that reward comes most meaningfully in its success. -

ZANT AUG 2009 Nlweb

ZANTZANT NEWSNEWS A Publication of Zoroastrian Association of North Texas www.zant.org August 2009 ZANT E VENTS ZZZOROASTRIAN CCCALENDAR IIINSIDE THIS IIISSUE Past Activities 2 • 8/15: Anand Bazaar (p. 3) • 8/7 - Farvardegan (K) • 8/9-8/18: Muktad Prayers (p.3 ) Upcoming Activities 2-3 • 8/9 - 8/18 Muktad (S) • 8/22: Shenshai New Year (p.3) Kid’s Corner 4 • 9/6: Farvardegan Jashan (p. 3) • 8/14 - Hamaspathmaedayem Gh. (S) • 9/12:Cooking Class (p.3) ZANT Center Update 5 • 9/13:Religious Class (p.4) • 8/19 - NouRuz (S) Zoroastrian Stimulus Plan 5 • 9/20:Paitishem Gahambar (p.8) • 8/24 - Khordad Sal (S) Treasurer’s Corner 6-7 • 8/29 - 9/2 Maidyozarem Gh. (K) Miscellaneous 8 Traveler’s Tales 8-9 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD BBBOARD OFOFOF DDDIRECTORS We continue to wish everyone a safe and enjoyable summer season. The ZANT Board is looking forward to celebrating all the upcoming festivities in President Kamran Behroozi our community. (972) 355-6607 Vice President Farieda Irani Treasurer Pearl P. Balsara Keep the smile, leave the tear. Secretary Khurshid Jamadar Think of joy, forget the fear. Social Director Keshvar Buhariwalla Hold the laughter, leave the pain. Director Roya Bidanjiry Director Delna Godiwalla Be joyous, because it's new year's day!! FEZANA Rep. Firdosh Mehta Mailing Address: Shenshai Nowroz Mubarak! P.O. Box 271117 Flower Mound, TX 75027-1117 ZANT Center : - ZANT Board 1605 Lopo Road Flower Mound, TX 75028-1306 We welcome and encourage feedback from our community. Please send comments or suggestions to [email protected] or mail to ZANT, P.O. -

Fezanabulletin

Newsletter of the Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America FEZANA bulletin December 2015 / VOLUME 5 • ISSUE 12 First Ever Iranshah Udvada Utsav The first Iranshah Udvada Utsav (IUU) celebration takes place over a three-day period from December 25-27, 2015 in Udvada, Gujarat, India. Inspired and supported by Hon’ble Shri Narendra Modi, Prime Minister of India, who speaks highly of the Zarathushti community’s unparalleled contribution towards India’s nation building, UPCOMING DATES the IUU will host thousands of Zarathushtis this December who will travel to Udvada from throughout India and from abroad to Through Jan 24, 2016 partake in the festivities. Prime Minister Modi Parsi Silk and Muslin from Iran, India and China Exhibition; East recognizes that Udvada (home of the West Center, Honolulu, HI. East Iranshah Atash Behram, the most sacred West Center Arts Program Atash Behram in India) showcases the history of the Parsi community and it was his Through September 2016 Persepolis: Images of an Empire. keen desire to project Udvada as a place of Oriental Institute – Univ of Chicago. harmony, religious tolerance and opportunities. Thus, after much hard work by its core project team, the first ever festival at Udvada has been organized, with the hope December 25-27, 2015 that it becomes an annual tradition. Iranshah Udvada Utsav (IUU); Udvada, India The program includes Parsi naataks, entertainment acts by children, youth and http://www.iuu.org.in/ adults of our community, Udvada heritage walks, treasure hunt, religious talks and Dec 28, 2015-Jan 2, 2016 other youth programs. Workshops and presentations are also planned which will 6th World Zoroastrian Youth showcase Parsi culture and traditions. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

The Hymns of Zoroaster: a New Translation of the Most Ancient Sacred Texts of Iran Pdf

FREE THE HYMNS OF ZOROASTER: A NEW TRANSLATION OF THE MOST ANCIENT SACRED TEXTS OF IRAN PDF M. L. West | 182 pages | 15 Dec 2010 | I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd | 9781848855052 | English | London, United Kingdom The Hymns of Zoroaster : M. L. West : See what's new with book lending at the Internet Archive. Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. User icon An illustration of a person's head and chest. Sign up Log in. Web icon An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine Texts icon An illustration of an open book. Books Video icon An illustration of two cells of a film strip. Video Audio icon An illustration of an audio speaker. Audio Software icon An illustration of a 3. Software Images icon An illustration of two photographs. Images Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape Donate Ellipses icon An illustration of text ellipses. Full text of " The Hymns Of Zoroaster. West has produced a lucid interpretation of those ancient words. His renditions are filled with insights and empathy. This endeavour is an important contribution toward understanding more fully some of the earliest prophetic words in human history. West's book will be widely welcomed, by students and general readers alike. West resuscitates the notion of Zoroaster as the self-conscious founder of a new religion. In advancing this idea, he takes position against many modern interpreters of these extremely difficult texts. The clarity and beauty of his translation will be much welcomed by students of Zoroastrianism and by Zoroastrians themselves, while his bold interpretation will spark off welcome debate among specialists. -

Comparison of Arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh Based on the Ancient Story of Bahmannameh

Propósitos y Representaciones May. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(3), e1092 ISSN 2307-7999 Current context of education and psychology in Europe and Asia e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 RESEARCH NOTES Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Comparación de la arrogancia en Shahnameh y Bahmannameh basada en la antigua historia de Bahmannameh Zohreh Amiri PhD student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Reza Ashrafzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Mohammad Shah Badiezadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Received 07-08-20 Revised 08-10-20 Accepted 09-02-20 On line 03-06-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Amiri, Z., Ashrafzadeh, R., & Shah Badiezadeh, M. (2021). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE3), e1092. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. Este artículo se distribuye bajo licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Summary One of the most important aspects of the struggle of warriors and warriors in epic works is the arrogance that is called by the comrades before the start of the hand-to-hand battle. It is accompanied by pride in ancestry, race, and ridicule. -

What an Auspicious Day Today Is! It Is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb's Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Ma

Weekly Zoroastrian Scripture Extract # 102 – Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Salgreh - Adar Mahino and Adar Roj Parab - We approach Thee Ahura Mazda through Thy Holy Fire - Yasna Haptanghaaiti - Moti Haptan Yasht - Yasna 36 Verses 1 - 3 Hello all Tele Class friends: What an auspicious day today is! It is Pak Iranshah Atash Behram Padshah Saheb’s Salgreh – Adar Mahino and Adar Roj! Adar Mahina nu Parab! Today in our Udvada Gaam, hundreds of Humdins from all over India will congregate to pay their homage to Padshah Saheb and then all of them will be treated by a sumptuous Gahambar Lunch thanks to the Petit Family, an annual event! Over 1500 Humdins will partake this Gahambar lunch! I have attached 3 photos of the Salgreh in 2004 showing the long queue, Gahambar lunch Pangat and the Master Chefs! In our religion, Fire is regarded as one of the most amazing creations of Dadar Ahura Mazda! In fact, in Atash Nyayesh, Fire is referred to as the Son of Ahura Mazda! In our Agiyaris, Adarans and Atash Behrams, the focal point of our worship is the consecrated Fire and hence many people call us Fire Worshippers in their ignorance. That brings to mind the famous quote of the great Persian poet, Ferdowsi, the Shahnameh Author: “Ma gui keh Atash parastand budan, Parastandeh Pak Yazdaan budan!” “Do not say that they are Fire Worshippers! They are worshippers of Pak Yazdaan (Dadar Ahura Mazda) (through Holy Fire!)” In our previous weeklies, we have presented verses from Atash Nyayesh in praise of our consecrated Fires! The above point by Ferdowsi is well supported by the second Karda (chapter) of Yasna Haptanghaaiti, Yasna 36, the seven Has (chapters) attributed by some to Zarathushtra himself after his Gathas and many attribute them to the immediate disciples of Zarathushtra. -

Volume 1 on Stage/ Off Stage

lives of the women Volume 1 On Stage/ Off Stage Edited by Jerry Pinto Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media Supported by the Laura and Luigi Dallapiccola Foundation Published by the Sophia Institute of Social Communications Media, Sophia Shree B K Somani Memorial Polytechnic, Bhulabhai Desai Road, Mumbai 400 026 All rights reserved Designed by Rohan Gupta be.net/rohangupta Printed by Aniruddh Arts, Mumbai Contents Preface i Acknowledgments iii Shanta Gokhale 1 Nadira Babbar 39 Jhelum Paranjape 67 Dolly Thakore 91 Preface We’ve heard it said that a woman’s work is never done. What they do not say is that women’s lives are also largely unrecorded. Women, and the work they do, slip through memory’s net leaving large gaps in our collective consciousness about challenges faced and mastered, discoveries made and celebrated, collaborations forged and valued. Combating this pervasive amnesia is not an easy task. This book is a beginning in another direction, an attempt to try and construct the professional lives of four of Mumbai’s women (where the discussion has ventured into the personal lives of these women, it has only been in relation to the professional or to their public images). And who better to attempt this construction than young people on the verge of building their own professional lives? In learning about the lives of inspiring professionals, we hoped our students would learn about navigating a world they were about to enter and also perhaps have an opportunity to reflect a little and learn about themselves. So four groups of students of the post-graduate diploma in Social Communications Media, SCMSophia’s class of 2014 set out to choose the women whose lives they wanted to follow and then went out to create stereoscopic views of them. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid