Leopard and Its Mythological-Epic Motifs in Shahnameh and Four Other Epic Works (Garshasbnameh, Kushnameh, Bahmannameh and Borzunameh)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iranshah Udvada Utsav

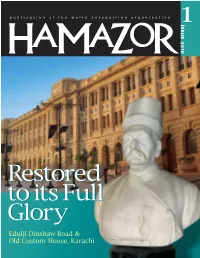

HAMAZOR - ISSUE 1 2016 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Physicist Extraordinaire, p 43 C o n t e n t s 04 WZO Calendar of Events 05 Iranshah Udvada Utsav - vahishta bharucha 09 A Statement from Udvada Samast Anjuman 12 Rules governing use of the Prayer Hall - dinshaw tamboly 13 Various methods of Disposing the Dead 20 December 25 & the Birth of Mitra, Part 2 - k e eduljee 22 December 25 & the Birth of Jesus, Part 3 23 Its been a Blast! - sanaya master 26 A Perspective of the 6th WZYC - zarrah birdie 27 Return to Roots Programme - anushae parrakh 28 Princeton’s Great Persian Book of Kings - mahrukh cama 32 Firdowsi’s Sikandar - naheed malbari 34 Becoming my Mother’s Priest, an online documentary - sujata berry COVER 35 Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE - cyrus cowasjee Image of the Imperial 39 Eduljee Dinshaw Road Project Trust - mohammed rajpar Custom House & bust of Mr Edulji Dinshaw, CIE. & jameel yusuf which stands at Lady 43 Dr Nergis Mavalvala Dufferin Hospital. 44 Dr Marlene Kanga, AM - interview, kersi meher-homji PHOTOGRAPHS 48 Chatting with Ami Shroff - beyniaz edulji 50 Capturing Histories - review, freny manecksha Courtesy of individuals whose articles appear in 52 An Uncensored Life - review, zehra bharucha the magazine or as 55 A Whirlwind Book Tour - farida master mentioned 57 Dolly Dastoor & Dinshaw Tamboly - recipients of recognition WZO WEBSITE 58 Delhi Parsis at the turn of the 19C - shernaz italia 62 The Everlasting Flame International Programme www.w-z-o.org 1 Sponsored by World Zoroastrian Trust Funds M e m b e r s o f t h e M a n a g i -

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and Dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract

Date:12/1/18 A Comparative Analysis of Educational Teaching in Shahnameh and Iliad Elhamshahverdi and dr.Masoodsepahvandi Abstract Ferdowsi's Shahnameh and Homer's Iliad are among the first literary masterpieces of Iran and Greece. These teachings include the educational teachings of Zal and Roudabeh, and Paris and Helen. This paper presents a comparative look at the immortal effect of this Iranian poet with Homer's poem-- the Greek blind poet. In this comparison, using a content analysis method, the effects of the educational teachings of these two stories are extracted and expressed, The results of this study show that the human and universal educational teachings of Shahnameh are far more than that of Homer's Iliad. Keywords: teachings, education,analysis,Shahname,Iliad. Introduction The literature of every nation is a mirror of the entirety of thought, culture and customs of that nation, which can be expressed in elegance and artistic delicacy in many different ways. Shahnameh and Iliad both represent the literature of the two peoples of Iran and Greece, which contain moral values for the happiness of the individual and society. "The most obvious points of Shahnameh are its advice and many examples and moral commands. To do this, Ferdowsi has taken every opportunity and has made every event an excuse. Even kings and warriors are used for this purpose. "Comparative literature is also an important foundation for the exodus of indigenous literature from isolation, and it will be a part of the entire literary heritage of the world, exposed to thoughts and ideas, and is also capable of helping to identify contemplation legacies in the understanding and friendship of the various nations."(Ghanimi, 44: 1994) Epic literature includes poems that have a spiritual aspect, not an individual one. -

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected]

Classical Persian Literature Bahman Solati (Ph.D), 2015 University of California, Berkeley [email protected] Introduction Studying the roots of a particular literary history enables us to better understand the allusions the literature transmits and why we appreciate them. It also allows us to foresee how the literature may progress.1 I will try to keep this attitude in the reader’s mind in offering this brief summary of medieval Persian literature, a formidable task considering the variety and wealth of the texts and documentation on the subject.2 In this study we will pay special attention to the development of the Persian literature over the last millennia, focusing in particular on the initial development and background of various literary genres in Persian. Although the concept of literary genres is rather subjective and unstable,3 reviewing them is nonetheless a useful approach for a synopsis, facilitating greater understanding, deeper argumentation, and further speculation than would a simple listing of dates, titles, and basic biographical facts of the giants of Persian literature. Also key to literary examination is diachronicity, or the outlining of literary development through successive generations and periods. Thriving Persian literature, undoubtedly shaped by historic events, lends itself to this approach: one can observe vast differences between the Persian literature of the tenth century and that of the eleventh or the twelfth, and so on.4 The fourteenth century stands as a bridge between the previous and the later periods, the Mongol and Timurid, followed by the Ṣafavids in Persia and the Mughals in India. Given the importance of local courts and their support of poets and writers, it is quite understandable that literature would be significantly influenced by schools of thought in different provinces of the Persian world.5 In this essay, I use the word literature to refer to the written word adeptly and artistically created. -

Comparison of Arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh Based on the Ancient Story of Bahmannameh

Propósitos y Representaciones May. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(3), e1092 ISSN 2307-7999 Current context of education and psychology in Europe and Asia e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 RESEARCH NOTES Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Comparación de la arrogancia en Shahnameh y Bahmannameh basada en la antigua historia de Bahmannameh Zohreh Amiri PhD student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Reza Ashrafzadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Mohammad Shah Badiezadeh Professor of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Mashhad Branch, Iran Received 07-08-20 Revised 08-10-20 Accepted 09-02-20 On line 03-06-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Amiri, Z., Ashrafzadeh, R., & Shah Badiezadeh, M. (2021). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9(SPE3), e1092. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE3.1092 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. Este artículo se distribuye bajo licencia CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Internacional (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Comparison of arrogance in Shahnameh and Bahmannameh based on the ancient story of Bahmannameh Summary One of the most important aspects of the struggle of warriors and warriors in epic works is the arrogance that is called by the comrades before the start of the hand-to-hand battle. It is accompanied by pride in ancestry, race, and ridicule. -

Compare and Analyzing Mythical Characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh

WALIA journal 31(S4): 121-125, 2015 Available online at www.Waliaj.com ISSN 1026-3861 © 2015 WALIA Compare and analyzing mythical characters in Shahname and Garshasb Nāmeh Mohammadtaghi Fazeli 1, Behrooze Varnasery 2, * 1Department of Archaeology, Shushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shushtar, Iran 2Department of Persian literature Shoushtar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shoushtar Iran Abstract: The content difference in both works are seen in rhetorical Science, the unity of epic tone ,trait, behavior and deeds of heroes and Kings ,patriotism in accordance with moralities and their different infer from epic and mythology . Their similarities can be seen in love for king, obeying king, theology, pray and the heroes vigorous and physical power. Comparing these two works we concluded that epic and mythology is more natural in the Epic of the king than Garshaseb Nameh. The reason that Ferdowsi illustrates epic and mythological characters more natural and tangible is that their history is important for him while Garshaseb Nameh looks on the surface and outer part of epic and mythology. Key words: The epic of the king;.Epic; Mythology; Kings; Heroes 1. Introduction Sassanid king Yazdgerd who died years after Iran was occupied by muslims. It divides these kings into *Ferdowsi has bond thought, wisdom and culture four dynasties Pishdadian, Kayanids, Parthian and of ancient Iranian to the pre-Islam literature. sassanid.The first dynasties especially the first one Garshaseb Nameh has undoubtedly the most shares have root in myth but the last one has its roots in in introducing mythical and epic characters. This history (Ilgadavidshen, 1999) ballad reflexes the ethical and behavioral, trait, for 4) Asadi Tusi: The Persian literature history some of the kings and Garshaseb the hero. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

The La Trobe Journal No. 91 June 2013 Endnotes Notes On

Endnotes NB: ‘Scollay’ refers to Susan Scollay, ed., Love and Devotion: from Persia and beyond, Melbourne: Macmillan Art Publishing in association with the State Library of Victoria and the Bodleian Library, 2012; reprinted with new covers, Oxford: The Bodleian Library, 2012. Melville, The ‘Arts of the Book’ and the Diffusion of Persian Culture 1 This article is a revised version of the text of the ‘Keynote’ lecture delivered in Melbourne on 12 April 2012 to mark the opening of the conference Love and Devotion: Persian cultural crossroads. It is obviously not possible to reproduce the high level of illustrations that accompanied the lecture; instead I have supplied references to where most of them can be seen. I would like to take this opportunity to thank all those at the State Library of Victoria who worked so hard to make the conference such a success, and for their warmth and hospitality that made our visit to Melbourne an unrivalled pleasure. A particular thanks to Shane Carmody, Robert Heather and Anna Welch. 2 The exhibition Love and Devotion: from Persia and beyond was held in Melbourne from 9 March to 1 July 2012 with a second showing in Oxford from 29 November 2012 to 28 April 2013. It was on display at Oxford at the time of writing. 3 Scollay. 4 For a recent survey of the issues at stake, see Abbas Amanat and Farzin Vejdani, eds., Iran Facing Others: identity boundaries in a historical perspective, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012; the series of lectures on the Idea of Iran, supported by the Soudavar Memorial Foundation, has now spawned five volumes, edited by Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis and Sarah Stewart, vols. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Persian 2704 SP15.Pdf

Attention! This is a representative syllabus. The syllabus for the course you are enrolled in will likely be different. Please refer to your instructor’s syllabus for more information on specific requirements for a given semester. THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Persian 2704 Introduction to Persian Epic Instructor: Office Hours: Office: Email: No laptops, phones, or other mobile devices may be used in class. This course is about the Persian Book of Kings, Shahnameh, of the Persian poet Abulqasim Firdawsi. The Persian Book of Kings combines mythical themes and historical narratives of Iran into a mytho-historical narrative, which has served as a source of national and imperial consciousness over centuries. At the same time, it is considered one of the finest specimen of Classical Persian literature and one of the world's great epic tragedies. It has had an immense presence in the historical memory and political culture of various societies from Medieval to Modern, in Iran, India, Central Asia, and the Ottoman Empire. Yet a third aspect of this monumental piece of world literature is its presence in popular story telling tradition and mixing with folk tales. As such, a millennium after its composition, it remains fresh and rife in cultural circles. We will pursue all of those lines in this course, as a comprehensive introduction to the text and tradition. Specifically, we will discuss the following in detail: • The creation of Shahname in its historical context • The myth and the imperial image in the Shahname • Shahname as a cornerstone of “Iranian” identity. COURSE MATERIAL: • Shahname is available in English translation. -

Iran 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is an authoritarian theocratic republic with a Shia Islamic political system based on velayat-e faqih (guardianship of the jurist). Shia clergy, most notably the rahbar (supreme leader), and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate key power structures. The supreme leader is the head of state. The members of the Assembly of Experts are nominally directly elected in popular elections. The assembly selects and may dismiss the supreme leader. The candidates for the Assembly of Experts, however, are vetted by the Guardian Council (see below) and are therefore selected indirectly by the supreme leader himself. Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has held the position since 1989. He has direct or indirect control over the legislative and executive branches of government through unelected councils under his authority. The supreme leader holds constitutional authority over the judiciary, government-run media, and other key institutions. While mechanisms for popular election exist for the president, who is head of government, and for the Islamic Consultative Assembly (parliament or majles), the unelected Guardian Council vets candidates, routinely disqualifying them based on political or other considerations, and controls the election process. The supreme leader appoints half of the 12-member Guardian Council, while the head of the judiciary (who is appointed by the supreme leader) appoints the other half. Parliamentary elections held in 2016 and presidential elections held in 2017 were not considered free and fair. The supreme leader holds ultimate authority over all security agencies. Several agencies share responsibility for law enforcement and maintaining order, including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security and law enforcement forces under the Interior Ministry, which report to the president, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to the supreme leader. -

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Feroza Fitch of Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA FEZANA JOURNAL ZEMESTAN 1379 AY 3748 ZRE VOL. 24, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2010 JOURJO N AL Dae – Behman – Spendarmad 1379 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1380 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1380 AY (Kadimi) CELEBRATING 1000 YEARS Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh: The Soul of Iran HAPPY NEW YEAR 2011 Also Inside: Earliest surviving manuscripts Sorabji Pochkhanawala: India’s greatest banker Obama questioned by Zoroastrian students U.S. Presidential Executive Mission PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 24 No 4 Winter / December 2010 Zemestan 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor: Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] 6 Financial Report Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 8 FEZANA UPDATE-World Youth Congress [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 12 SHAHNAMEH-the Soul of Iran Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] 50 IN THE NEWS Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla Subscription Managers: Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected];