Life Writing in Hip-Hop: How Open Mike Eagle Resists Performative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

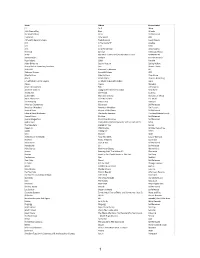

2015 Year in Review

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

Reiter Und Die Von Ihnen Gerittenen Pferde Buchstabe

Reiter und die von ihnen gerittenen Pferde 1983 - 2013 Buchstabe: W (Vollversion) Wachslander, Nadine Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Almansor 1 1999 1999 Auriva 1 1998 1998 Gewandte 1 1998 1998 My Lady 1 1999 1999 Rotary 1 1998 1998 Schlaudius 1 1998 1998 Wachtarz, Gabriele Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Dominikaner 6 1 1983 1983 Grevinna 5 1983 1983 Cashew 3 1983 1983 Wachtänzer 1 1983 1983 Wächter, Jennifer Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Tavit 2 1 1990 1991 Akropolis 2 1991 1992 Meridian 1 1991 1991 Svatka 1 1991 1991 Sweet Sunset 1 1991 1991 Youbana 1 1991 1991 Wada, Ryuji Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Alesi 1 2002 2002 Fleurie Domaine 1 2002 2002 Lobos 1 2002 2002 Muskatsturm 1 2002 2002 Night Woman 1 2002 2002 Sangarra 1 2002 2002 Santo Domingo 1 2002 2002 Think Twice 1 2002 2002 Wagener, Annette Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Limerick 2 1998 1998 Mon Apro 1 1998 1998 Rudkin 1 1998 1998 Wagner, F. Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Bepeen 3 1988 1989 White of Morn 2 1 1988 1988 Dr. Caligary 2 1990 1990 Tedesco 2 1989 1990 Upper Dan 2 1988 1988 Gameshow 1 1 1990 1990 Champagner 1 1988 1988 Latour Maubourg 1 1988 1988 Ottavio 1 1988 1988 Skymood 1 1990 1990 Yanouk 1 1988 1988 Wagner, Janine Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Altivo 1 1997 1997 Wagner, Nina Pferd Starts Siege Jahr-von Jahr-bis Anastra 7 3 2009 2009 Abrafax 7 1 2009 2011 Pixie Dust 6 2 2009 2012 Le Papillon 6 1 2009 2009 Glücksfeuer 6 2010 2011 Adenike 5 2011 2012 Flying Encore 5 2011 2012 Malachi 5 2012 2012 Pantano 5 2008 2009 Practical -

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Michelle Chang IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Josephine Lee, Co-Advisor Elliott Powell, Co-Advisor December 2020 © Michelle Chang 2020 i Acknowledgements As I write the last section of my dissertation, I find myself at a loss for words. 55,000+ words later and my writing fails me. While the dissertation itself is an overwhelming feat, this acknowledgements section feels equally heavy. Expressing my gratitude and thanks for every person who has made this possiBle feels quite impossiBle. And as someone who once detested both school and writing, there’s a lot of people I am thankful for. It is a fact that I could not completed a PhD, let alone a dissertation, on my own. Graduate school wears you down, and especially one framed By the 2016 presidential election and 2020 uprisings, rise of white supremacy, and a gloBal pandemic, graduate school is really hard and writing is the last thing you want to do. While I’ve spent days going through mental lists of people and groups who’ve helped me, this is not a complete list and my sincere apologies to anyone I’ve forgotten. First and foremost, this dissertation would not be where it is today without the guidance and support of my advisors Jo Lee and Elliott Powell. The hours of advice and words of wisdom I received from you both not only shaped my project and affirmed its direction, but they also reminded me of the realistic expectations we should have for ourselves. -

Sept. 7-13, 2017

SEPT. 7-13, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM • FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE GET THE GEAR YOU WANT TODAY! 48MONTHS 0% INTEREST*** ON 140+ TOP BRANDS | SOME RESTRICTIONS APPLY 36MONTHS 0% INTEREST** ON 100+ TOP BRANDS | SOME RESTRICTIONS APPLY WHEN YOU USE THE SWEETWATER CARD. 36/48 EQUAL MONTHLY PAYMENTS REQUIRED. SEE STORE FOR DETAILS. NOW THROUGH OCTOBER 2 5501 US Hwy 30 W • Fort Wayne, IN Music Store Hours: Mon–Thurs 9–9 • Fri 9–8 Sat 9–7 • Sun 11–5 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com ---------------------------------------------------------- September 7, 2017 whatzup Volume 22, Number 6 e’re calling this our Big Fat Middle Waves issue since our cover features the MAIN STAGE: festival, now in its second year, and we’ve got a 16-page guide to all things • A Dancer’s Legacy – SEP 22 & 23 Middle Waves inside. Check out Steve Penhollow’s feature story on page 4, • The Nutcracker – DEC 1 thru 10 Wread the guide cover to cover and on the weekend of Sept. 15-16 keep whatzup.com pulled up on your mobile phone’s web browser. We’ll be posting Middle Waves updates • Coppélia – MAR 23-25 all day long so you’ll always know what’s happening where. • Academy Showcase – MAY 24 If you’ve checked out whatzup.com lately, you’ve probably noticed the news feed. It’s FAMILY SERIES: the home page on mobile phones and one of the four tabs on the PC version, and it THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28 allows our whatzup advertisers to talk directly to whatzup.com users. If you’re one of • Frank E. -

MUSIDREVIEW Mr

MUSIDREVIEW TEXT BYJOEL MARASIGAN mr >WE HIT HARD...LIKE IKE TURNER THE PLATFORM ry lesson on the "language" of the DJ. "Head 2 Head" mimics a boxing match where Dialated Peoples/Capitol Records Spinbad and Rev exchange battle-dj blows. If that isn’t enough, 13 emcees and six True hip-hop lyrical skills and world-class turntablism are what entitle Evidence, Rakaa ’tablists team up to help assist in eight of the 20 inspiring tracks. This is a must- (Iriscience) and DJ Babu are about, as they explore the surface of hip-POP without have LP. Revolution has caused one. fearing contamination of their years spent accumulating underground credibility. Their NuGruv.com first release—a crowd-rocking, emcee jaw-dropper—"Work the Angles" surprisingly Wakeupshow.com takes second-stage to cuts like "No Retreat," and "The Shape of Things to Come." Courtesy Cheapshot at Score Press Moreover, the inclusion of B Real, Tha Alkaholiks, Aceyalone, Planet Asia, Defari, White E. Ford (Everlast) and Phil Tha’ Agony furnish just enough aural trickery to make you UNDERGROUND RAILROAD believe you bought more than The Platform’s 16 tracks. Open your eyes, Dilated Masterminds/NuGruv Alliance/Ground Control Peoples is like a dime surrounded by pennies—smaller but worth much more. New York’s Oracle, Kimani and Epod, the Masterminds, come to collect with this Dialatedpeoples.com debut LP and with bars from L-Fudge, Mr. Lif, J-Treds, Shabaam Sahdeeq, Mr. Hollywoodandvine.com Complex, J-Live and EL-P combo’d with the production of Mr. Khaliyl (of the Bush Courtesy Cheapshot at Score Press Babees), come packed with explosive beats and sword-sharp lyrics. -

Andrew WK Lets Absurdism Flow at Largo | Pop & Hiss

Live review: Andrew W.K. lets absurdism flow at Largo | Pop ... http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/music_blog/2009/10/live-revie... Like 72K Subscribe/Manage Account Place Ad LAT Store Jobs Cars Real Estate Rentals Classifieds Custom Publishing ENTERTAINMENT LOCAL U.S. WORLD BUSINESS SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT HEALTH LIVING TRAVEL OPINION DEALS Weekly Ad MOVIES TELEVISION MUSIC CELEBRITY ARTS & CULTURE COMPANY TOWN CALENDAR THE ENVELOPE FINDLOCAL IN THE NEWS: JUSTIN BIEBER 'CELEBRITY APPRENTICE' DAVID SCHWIMMER 'GAME OF THRONES' PRINCESS BEATRICE Search Pop & Hiss L.A. Times on Facebook Like 72K THE L.A. TIMES MUSIC BLOG Supreme Court orders California to release tens of thousands of prison inmates « Previous Post | Pop & Hiss Home | Next Post » 16,402 people shared this. In Joplin, there was no time to Live review: Andrew W.K. lets absurdism flow at Largo prepare 459 people shared this. October 9, 2009 | 3:28 pm (0) (2) Comments (0) Senate votes to extend Patriot Act 313 people shared this. advertisement Stay connected: About the Bloggers The musician lets his avant-garde tendencies soar with the Calder Quartet. Chris Barton Andrew W.K. had just finished a piano-and-string-quartet version of his pop-metal hit "Party Hard" August Brown on Thursday night when a young man from the audience bum-rushed the stage at Largo at the Gerrick Kennedy Coronet. There he stood, seemingly waiting for another of W.K.'s jubilant rockers like "Party Til You Randy Lewis Puke" or "It's Time to Party." Todd Martens Ann Powers Instead, W.K. (whose given last name is Wilkes-Krier) and the renowned chamber group the Calder Randall Roberts Quartet opted to play two versions of John Cage's entirely silent composition "4:33." Margaret Wappler It made for a bit of a transcendently awkward moment for the enthusiastic fan, who rifled in his pockets and looked genuinely confused at this turn of events. -

SXSW2016 Music Full Band List

P.O. Box 685289 | Austin, Texas | 78768 T: 512.467.7979 | F: 512.451.0754 sxsw.com PRESS RELEASE - FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SXSW Music - Where the Global Community Connects SXSW Music Announces Full Artist List and Artist Conversations March 10, 2016 - Austin, Texas - Every March the global music community descends on the South by Southwest® Music Conference and Festival (SXSW®) in Austin, Texas for six days and nights of music discovery, networking and the opportunity to share ideas. To help with this endeavor, SXSW is pleased to release the full list of over 2,100 artists scheduled to perform at the 30th edition of the SXSW Music Festival taking place Tuesday, March 15 - Sunday, March 20, 2016. In addition, many notable artists will be participating in the SXSW Music Conference. The Music Conference lineup is stacked with huge names and stellar latebreak announcements. Catch conversations with Talib Kweli, NOFX, T-Pain and Sway, Kelly Rowland, Mark Mothersbaugh, Richie Hawtin, John Doe & Mike Watt, Pat Benatar & Neil Giraldo, and more. All-star panels include Hired Guns: World's Greatest Backing Musicians (with Phil X, Ray Parker, Jr., Kenny Aranoff, and more), Smart Studios (with Butch Vig & Steve Marker), I Wrote That Song (stories & songs from Mac McCaughan, Matthew Caws, Dan Wilson, and more) and Organized Noize: Tales From the ATL. For more information on conference programming, please go here. Because this is such an enormous list of artists, we have asked over thirty influential music bloggers to flip through our confirmed artist list and contribute their thoughts on their favorites. The 2016 Music Preview: the Independent Bloggers Guide to SXSW highlights 100 bands that should be seen live and in person at the SXSW Music Festival. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zc4f1mk Author Hur, David Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by David Hur Committee in charge: Professor Yunte Huang, co-Chair Professor Stephanie Batiste, co-Chair Professor erin Khuê Ninh Professor Sowon Park September 2020 The dissertation of David Hur is approved. ____________________________________________ erin Khuê Ninh ____________________________________________ Sowon Park ____________________________________________ Stephanie Batiste, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Yunte Huang, Committee Co-Chair September 2020 Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Copyright © 2020 by David Hur iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey has been made possible with support from faculty and staff of both the Comparative Literature program and the Department of Asian American Studies. Special thanks to Catherine Nesci for providing safe passage. I would not have had the opportunities for utter trial and error without the unwavering support of my committee. Thanks to Yunte Huang, for sharing poetry in forms of life. Thanks to Stephanie Batiste, for sharing life in forms of poetry. Thanks to erin Khuê Ninh, for sharing countless virtuous lessons. And many thanks to Sowon Park, for sharing in the witnessing. -

Nostalgia in Indie Folk by Claire Coleman

WESTERN SYDNEY UNIVE RSITY Humanities and Communication Arts “Hold on, hold on to your old ways”: Nostalgia in Indie Folk by Claire Coleman For acceptance into the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 20, 2017 Student number 17630782 “Hold on, hold on to your old ways” – Sufjan Stevens, “He Woke Me Up Again,” Seven Swans Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................................................. Claire Coleman Acknowledgements This thesis could not have been completed without the invaluable assistance of numerous colleagues, friends and family. The love, respect and practical support of these people, too many to name, buoyed me through the arduous privilege that is doctoral research. With special thanks to: The Supers – Dr Kate Fagan, Mr John Encarnacao and Associate Prof. Diana Blom My beloved – Mike Ford My family – Nola Coleman, Gemma Devenish, Neale Devenish, and the Fords. The proof-readers – Alex Witt, Anna Dunnill, Pina Ford, Connor Weightman and Nina Levy. My choir families – Menagerie, Berlin Pop Ensemble and Dienstag Choir Administrative staff at Western Sydney University Dr Peter Elliott Ali Kirby, Kate Ballard, Carol Shepherd, Kathryn Smith, Judith Schroiff, Lujan Cordaro, Kate Ford and the many cafes in Perth, Sydney and Berlin -

BLAHZAY BLAHZAY Blah Blah Blah NO EXPORT to EUROPE

BLAHZAY BLAHZAY Blah Blah Blah NO EXPORT TO EUROPE KEY SELLING POINTS • First time to ever be reissued on vinyl since original 1996 release on Fader Records • Features original artwork from the official release • Limited edition of 1000 hand-numbered copies DESCRIPTION ARTIST: Blahzay Blahzay In August 1996, a Brooklyn duo consisting of MC Outloud and DJ TITLE: Blah Blah Blah P.F. Cuttin, better known to the world as Blahzay Blahzay, released CATALOG: l-TKR003 “Blah Blah Blah”, their one and only album, on Fader Records. The LABEL: Tuff Kong Records album’s 13 tracks proudly waved the flag of the East, featuring hit GENRE: Hip-Hop single “Danger”, as well as other bangers such as “Pain I Feel”, “Good BARCODE: 659123084215 Cop/Bad Cop” and “Danger - Part 2” (featuring Smoothe Da Hustler, FORMAT: 2XLP Trigger Tha Gambler and Wu-Tang affiliate La the Darkman). The RELEASE: 6/30/2017 combination of PF Cuttin’s polished beats and Outloud’s aggressive LIST PRICE: $31.98 / FB lyrical style made this album a classic for all underground hip-hop heads. TRACKLISTING 1. Intro Twenty-one years after its original release, Blahzay Blahzay have 2. Blah, Blah, Blah teamed up with Italian independent record label Tuff Kong Records 3. Medina’s In Da House to bring back their legendary “Blah Blah Blah” LP. This spring, Tuff 4. Danger - Part 2 (feat. La The Darkman, Smoothe Da Hustler, Kong Records will be releasing the album on 2LP, re-mastered for Trigger Tha Gambler) vinyl and featuring the original artwork, as a limited edition run of 5. -

From Soul Syndicate to Super Scholar: Portia K. Maultsby

ARCHIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MUSIC AND CULTURE liner notesNO. 18 / 2013-2014 From Soul Syndicate to Super Scholar: Portia K. Maultsby aaamc liner notes 18 0214.indd 1 2/24/14 2:58 PM aaamc mission From the Desk of the Director The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, preservation, and dissemination of materials for the purpose of research and study of African American music and culture. www.indiana.edu/~aaamc Table of Contents From the Desk of the Director .....................2 In the Vault: Recent Donations .................3 Portia Maultsby and Mellonee Burnim. Photo by Chris Meyer, courtesy of Indiana University. Featured Collection: Black Gospel Music in the Today I write my last director’s column Advisory Board, who have donated Netherlands .........................4 for Liner Notes as I prepare to retire materials and promoted the work of after a forty-two-year career at Indiana the archives, assisted in identifying and IU Embarks on 5-Year University. One of my most rewarding acquiring collections, offered ideas for Media Digitization and activities during this long residency has programs and development projects, Preservation Initiative ...........6 been my work as founding director of and provided general counsel. I take this the Archives of African American Music opportunity to publicly thank them for From Soul Syndicate and Culture. From the outset, my goal their unwavering support over the years. to Super Scholar: was to establish an archives with a focus I also acknowledge the archives’ Portia K. Maultsby ................7 on black musical and cultural traditions, superb and dedicated full-time and including popular and religious music, student staff, who offered many creative The AAAMC Welcomes personality radio of the post-World War II ideas for collection development, public Incoming Director era, and the musical legacy of Indiana, that Mellonee Burnim ................15 programs, and marketing activities largely had been excluded (jazz being the over the past twenty-two years.