Leimert Park the History/Key Places

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Michelle Chang IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Josephine Lee, Co-Advisor Elliott Powell, Co-Advisor December 2020 © Michelle Chang 2020 i Acknowledgements As I write the last section of my dissertation, I find myself at a loss for words. 55,000+ words later and my writing fails me. While the dissertation itself is an overwhelming feat, this acknowledgements section feels equally heavy. Expressing my gratitude and thanks for every person who has made this possiBle feels quite impossiBle. And as someone who once detested both school and writing, there’s a lot of people I am thankful for. It is a fact that I could not completed a PhD, let alone a dissertation, on my own. Graduate school wears you down, and especially one framed By the 2016 presidential election and 2020 uprisings, rise of white supremacy, and a gloBal pandemic, graduate school is really hard and writing is the last thing you want to do. While I’ve spent days going through mental lists of people and groups who’ve helped me, this is not a complete list and my sincere apologies to anyone I’ve forgotten. First and foremost, this dissertation would not be where it is today without the guidance and support of my advisors Jo Lee and Elliott Powell. The hours of advice and words of wisdom I received from you both not only shaped my project and affirmed its direction, but they also reminded me of the realistic expectations we should have for ourselves. -

MUSIDREVIEW Mr

MUSIDREVIEW TEXT BYJOEL MARASIGAN mr >WE HIT HARD...LIKE IKE TURNER THE PLATFORM ry lesson on the "language" of the DJ. "Head 2 Head" mimics a boxing match where Dialated Peoples/Capitol Records Spinbad and Rev exchange battle-dj blows. If that isn’t enough, 13 emcees and six True hip-hop lyrical skills and world-class turntablism are what entitle Evidence, Rakaa ’tablists team up to help assist in eight of the 20 inspiring tracks. This is a must- (Iriscience) and DJ Babu are about, as they explore the surface of hip-POP without have LP. Revolution has caused one. fearing contamination of their years spent accumulating underground credibility. Their NuGruv.com first release—a crowd-rocking, emcee jaw-dropper—"Work the Angles" surprisingly Wakeupshow.com takes second-stage to cuts like "No Retreat," and "The Shape of Things to Come." Courtesy Cheapshot at Score Press Moreover, the inclusion of B Real, Tha Alkaholiks, Aceyalone, Planet Asia, Defari, White E. Ford (Everlast) and Phil Tha’ Agony furnish just enough aural trickery to make you UNDERGROUND RAILROAD believe you bought more than The Platform’s 16 tracks. Open your eyes, Dilated Masterminds/NuGruv Alliance/Ground Control Peoples is like a dime surrounded by pennies—smaller but worth much more. New York’s Oracle, Kimani and Epod, the Masterminds, come to collect with this Dialatedpeoples.com debut LP and with bars from L-Fudge, Mr. Lif, J-Treds, Shabaam Sahdeeq, Mr. Hollywoodandvine.com Complex, J-Live and EL-P combo’d with the production of Mr. Khaliyl (of the Bush Courtesy Cheapshot at Score Press Babees), come packed with explosive beats and sword-sharp lyrics. -

UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zc4f1mk Author Hur, David Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by David Hur Committee in charge: Professor Yunte Huang, co-Chair Professor Stephanie Batiste, co-Chair Professor erin Khuê Ninh Professor Sowon Park September 2020 The dissertation of David Hur is approved. ____________________________________________ erin Khuê Ninh ____________________________________________ Sowon Park ____________________________________________ Stephanie Batiste, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Yunte Huang, Committee Co-Chair September 2020 Diasporic Ethnopoetics Through “Han-Gook”: An Inquiry into Korean American Technicians of the Enigmatic Copyright © 2020 by David Hur iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey has been made possible with support from faculty and staff of both the Comparative Literature program and the Department of Asian American Studies. Special thanks to Catherine Nesci for providing safe passage. I would not have had the opportunities for utter trial and error without the unwavering support of my committee. Thanks to Yunte Huang, for sharing poetry in forms of life. Thanks to Stephanie Batiste, for sharing life in forms of poetry. Thanks to erin Khuê Ninh, for sharing countless virtuous lessons. And many thanks to Sowon Park, for sharing in the witnessing. -

Sample Some of This

Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (169) ✔ KEELY SMITH / I Wish You Love [Capitol (LP)] JEHST / Bluebells [Low Life (EP)] RAMSEY LEWIS TRIO / Concierto De Aranjuez [Cadet (LP)] THE COUP / The Liberation Of Lonzo Williams [Wild Pitch (12")] EYEDEA & ABILITIES / E&A Day [Epitaph (LP)] CEE-KNOWLEDGE f/ Sun Ra's Arkestra / Space Is The Place [Counterflow (12")] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Bernie's Tune ("Off Duty", O.S.T.) [Fontana (LP)] COMMON & MARK THE 45 KING / Car Horn (Madlib remix) [Madlib (LP)] GANG STARR / All For Da Ca$h [Cooltempo/Noo Trybe (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Theme From "Return From The Ashes", O.S.T. [RCA (LP)] 7 NOTAS 7 COLORES / Este Es Un Trabajo Para Mis… [La Madre (LP)] QUASIMOTO / Astronaut [Antidote (12")] DJ ROB SWIFT / The Age Of Television [Om (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Look Stranger (From BBC-TV Series) [RCA (LP)] THE LARGE PROFESSOR & PETE ROCK / The Rap World [Big Beat/Atlantic (LP)] JOHN DANKWORTH & HIS ORCHESTRA / Two-Piece Flower [Montana (LP)] GANG STARR f/ Inspectah Deck / Above The Clouds [Noo Trybe (LP)] Sample Some Of This, Sample Some Of That (168) ✔ GABOR SZABO / Ziggidy Zag [Salvation (LP)] MAKEBA MOONCYCLE / Judgement Day [B.U.K.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Look Of Love [Buddah (LP)] DIAMOND D & SADAT X f/ C-Low, Severe & K-Terrible / Feel It [H.O.L.A. (12")] GABOR SZABO / Love Theme From "Spartacus" [Blue Thumb (LP)] BLACK STAR f/ Weldon Irvine / Astronomy (8th Light) [Rawkus (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Sombrero Man [Blue Thumb (LP)] ACEYALONE / The Hunt [Project Blowed (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Gloomy Day [Mercury (LP)] HEADNODIC f/ The Procussions / The Drive [Tres (12")] GABOR SZABO / The Biz [Orpheum Musicwerks (LP)] GHETTO PHILHARMONIC / Something 2 Funk About [Tuff City (LP)] GABOR SZABO / Macho [Salvation (LP)] B.A. -

City of Angels

ZANFAGNA CHRISTINA ZANFAGNA | HOLY HIP HOP IN THE CITY OF ANGELSHOLY IN THE CITY OF ANGELS The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Lisa See Endowment Fund in Southern California History and Culture of the University of California Press Foundation. Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Holy Hip Hop in the City of Angels MUSIC OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Shana Redmond, Editor Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr., Editor 1. California Soul: Music of African Americans in the West, edited by Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje and Eddie S. Meadows 2. William Grant Still: A Study in Contradictions, by Catherine Parsons Smith 3. Jazz on the Road: Don Albert’s Musical Life, by Christopher Wilkinson 4. Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars, by William A. Shack 5. Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West, by Phil Pastras 6. What Is This Thing Called Jazz?: African American Musicians as Artists, Critics, and Activists, by Eric Porter 7. Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop, by Guthrie P. Ramsey, Jr. 8. Lining Out the Word: Dr. Watts Hymn Singing in the Music of Black Americans, by William T. Dargan 9. Music and Revolution: Cultural Change in Socialist Cuba, by Robin D. -

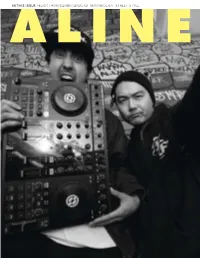

Fall 2011 Aline 1

IN THIS ISSUE MUSIC FROM DUMBFOUNDEAD MANAN DESAI STREET STYLE ALINE FALL 2011 ALINE 1 ALINE MAGAZINE FALL2011 UNIQUE TEAHOUSE The original boba house on SU Campus! 171 MARSHALL ST SYRACUSE, NY 2ND FLOOR T 315.422.7385 Dumbfoundead performs at Schine Underground COVER FASHION VIBE BITES Photography Zixi Wu //////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 8 TOXIC SOCIAL //////////////////////////////////////////////////////// //////////////////////////////////////////////////////// OPEN FROM Korean-American rapper The new trend of 17 ORIENTAL CHARM 23 KOLLABORATION 28 OBESITY IN ASIA Dumbfoundead (Jonathan light smoking gains The rise of the Asian Even without its founder Everyone's favorite Park) performs on stage ground among young model at major fash- at the helm, the ultimate clown has made Monday - Thursday 11AM - 12AM Nov. 5 at the Schine Stu- Asians here and ion houses Asian American talent inroads into Asia. Friday - Saturday dent Center. Get up close beyond competition continues And it looks like he's 12PM - 2AM and personal » 26 to wow here to stay 18 STREET SPY Sunday 12PM - 12AM Prowling campus ON CAMPUS 29 WHINE & DINE //////////////////////////////////////////////////////// streets with a 24 DUMBFOUNDEAD THIS ISSUE camera This Asian American Read about our 10 ON THE SOAPBOX battle rapper spits dining experience at The first hire for the Brickstone Eatery 4 EDITOR'S LETTER about freestylin, new AAA minor talks 20 FASHION'S YouTube, chasing girls, and Chorong House 5 MASTHEAD passions and life sto- NIGHT OUT and a record -

Abstract Rude

"...a skillful MC, capable of expressing extremely soulful sentiments with his mystical themes and deeply pronounced voice." -Robert Gabriel STREET DATE: 5.05.09 ABSTRACT RUDE REJUVENATION As a product of the legendary Goodlife open mic sessions, Abstract Rude splashed onto the scene in 1994 as part of the famed Project Blowed crew that included LA’s Freestyle Fellowship and Aceyalone. As one half of the A-Team (with Aceyalone), one third of Haiku D’Etat (with Aceyalone & Myka 9) and frontman of his group Abstract Tribe Unique (ATU), Ab Rude has RSE-0106-2 endeared himself to fans worldwide through consistent touring and genre Format: Compact Disc / 2LP defining albums such as 1999’s South Central Thynk Tank (currently out of CD Packaging: Recycled Digi Slider print). Once signed to the Beastie Boys Grand Royal imprint, Ab has readied LP Packaging: Full Color Jacket + himself to re-emerge with Rhymesayers Entertainment and his most consistent Digital Download Card and focused work to date, Rejuvenation. Box Lot: 30 File Under: Rap/Hip Hop “A” Produced entirely by Seattle super producer Vitamin D (G-Unit, Redman, Young Parental Advisory: Yes Buck, Gift of Gab, Choklate, Lifesavas, Black Sheep, etc.), Rejuvenation is Street Date: 5.05.09 a hard hitting soulful ryde showcasing Ab Rude’s distinct and unlimited vocal stylings. CD-826257010629 LP-826257010612 SELLING POINTS: +26257-ABAGCj +26257-ABAGBc •Produced by Vitamin D (G-Unit, Redman, Gift of Gab, etc.) •Features Project Blowed members Aceyalone & Myka 9 as DISCOUNT: 3% New Release Discount Until 5.05.09 well as the next generation of Blowedians Sahtyre, Alpha MC, Busdriver, Nocando, Open Mike & Dumbfoundead. -

Life Writing in Hip-Hop: How Open Mike Eagle Resists Performative

Life Writing in Hip-Hop: How Open Mike Eagle Resists Performative Acts of Masculinity and Race through Rap Raoul Markaban 4025997 MA Literature Today Thesis Supervisor: dr. Anna Poletti Second reader: dr. Mia You Markaban 2 Table of contents: Introduction 3 Chapter 1: existing scholarly debate 6 1990s 6 2000s 10 2010s 11 Chapter 2: Dark Comedy 13 Dark comedy 13 Qualifiers 15 Hip-hop appropriateness and breaking expectations 18 Voice 19 Chapter 3: Hella Personal Film Festival 22 Masculinity 22 Race 30 Chapter 4: Brick Body Kids Still Daydream 39 Robert Taylor Homes 39 Masculinity 41 ‘Brick Body Complex’ 48 Race 51 Conclusion 56 Works cited 59 Primary works: 59 Secondary works: 59 Works consulted 61 Markaban 3 Introduction Chicago native Michael W. Eagle II (born November 14, 1980), better known by his stage name Open Mike Eagle, is an American hip hop artist. In 2010, after being active in the hip-hop scene as part of the collective Project Blowed, he released his debut solo album: Unapologetic Art Rap. With the title of this album, Open Mike Eagle established the self proclaimed subgenre of ‘art rap’, which he would go on to embrace on many of his later albums. In a write-up on ‘art rap’ for Bandcamp Daily titled "A Walk Through the Avant-Garde World of 'Art Rap' Music”, Max Bell argues that the term ‘art rap’ is a reactionary phrase that responds directly to the subgenre of ‘art rock’, and implies that the existing set of sonic or lyrical conventions for hip-hop do not suffice for the message ‘art rappers’ tend to communicate. -

Jooyoung Lee

Open mic: professionalizing the rap career Jooyoung Lee Resumen ¿De qué modo cambian los significados de un local de hip hop durante la trayectoria de un rapero aspirante? Este artículo utiliza cuatro años de trabajo de campo etnográfico conti- nuado con varones de barrios marginados de la ciudad que rapean en el Project Blowed, un evento de ‘open mic’ de hip hop en la zona South Central de Los Ángeles. Aunque los rape- ros en un principio consideran al Project Blowed como un lugar en donde perfeccionar sus habilidades interpretativas y ganarse el respeto de sus pares, esperan poder dejarlo atrás y hacer dinero en la industria de la música. Los OGs, raperos mayores con experiencia, que siguen participando en esta escena actúan como mentores de los raperos más jóvenes, pero también pueden convertirse en ejemplos de las trayectorias estancas que los raperos emergentes quieren evitar. Este artículo explora cómo el modo en que los participantes perciben este local está vinculado a sus percepciones cambiantes de otros individuos de la escena. Hip hop; trayectorias de rap; cultura juvenil; South Central, Los Ángeles Abstract How do the meanings of a Hip Hop venue change over the aspiring rapper’s career? This article draws on four years of ongoing ethnographic fieldwork with inner-city men who rap at Project Blowed, a Hip Hop ‘open mic’ in South Central Los Angeles. While rappers ini- tially view Project Blowed as a place to hone their performance skills and earn the respect of their peers, they hope to move beyond it and make money in the music industry. -

Requiredaudio Heard Before the Herd Text Byjoel Marasigan

REQUIREDAUDIO HEARD BEFORE THE HERD TEXT BYJOEL MARASIGAN Califormula Mash Up Radio Vol. 2 Funkmaster Flex Carshow Tour Right About Now Ellay Khule Dj Muggs/DJ Warrior Funkmaster Flex (The Official Sucka Free Mix CD) Here’s an album for the hip and I didn’t think the first Mash Up There’s no doubt that Funkmaster Talib Kweli those that can smell hot shit before Radio Mixtape could be topped, but Flex has access to the hot shit. This Talib is fresh off his “Beautiful it’s even a fart. The early ‘90s I should get punched in the face for project alone boasts top-notch rap- Struggle” album with a mixtape. It’s “Project Blowed” album truly assem- thinking otherwise. I thought that pers: 50, Paul Wall, Cam’ron, Juelz actually more of a compilation of bled the best and most ahead-of- the first one was really good and it Santana, Mobb Deep, Nas, Jadakiss, cuts with random artists than it is a their-time Los Angeles MCs. Blowed- seemed that it’d be a cool, occa- Elephant Man, Xzibit, David Banner, blend or “DJ Clue” type tape. On this ian Ellay Khule takes a break from sional, mediocre, production among others. If, in fact, you don’t episode, you’ll find a couple about- the stage and hits the studio to release. I really should get punched listen to music, you must be into to-blow artists (Rhymefest, Jean blow a mic or two. Khule’s lyrics and in the face for my short-sighted- cars. -

Milestone 2003 Rev.Qxd

front cover ceramic by Milestone 2003 Lillian Barajas East Los Angeles College M i l e s t o n e 2 0 0 3 East Los Angeles College Jae Kang M i l e s t o n e 2 0 0 3 East Los Angeles College Monterey Park, California M i l e s t o n e 2 0 0 3 Editor, Advisor Carol Lem Selection Staff Creative Writing Class of Spring 2003 Book Design Trish Glover Photography Christine Moreno Ceramics Maricela Alvarez, Juan Arreano, Lillian Barajas, Jae Kang, David Kurland, Tomoko Morishita, Takeya Oe, Larry Ortega, Rosa Pinuelas, Gladys Quinonez, Rosendo Rodriquez, Tamara Shubin, Christopher Turk East Los Angeles College 1301 Avenida Cesar Chavez Monterey Park, California 91754 Milestone is published under the sponsorship of the East Los Angeles College English Department. Material is solicited from students of the college. The printing of Milestone was made possible through the generous support of the East Los Angeles College Foundation. “We suffocate among people who think they are absolutely right, whether in their machines or their ideas. And for all those who can live only in an atmosphere of human dialogue, the silence is the end of the world.” — Albert Camus M i l e s t o n e 2 0 0 3 3 Editor’s Notes n this warm summer morning I am sitting at my Odesk, hoping for the words to express themselves effortlessly and in perfect order. But I’ve been writing and teaching long enough to real- ize that the muse, the creative spirit, or the process just doesn’t work that way. -

NLB 6701 WISECRVCKER the Supreme Paradigm CD

WISECRVCKER SUPREME PARADIGM: THE GRAND SCHEME Sacred Algorithm (ft. The Grouch & Eligh of Living Legends) Do the Knowledge (ft. Sa Roc & 2mex of Visionaries) Tough Cookies (ft. Moka Only & Blueprint) Heavy Handed (ft. New Classic & Planet Asia) Cantankerous (ft. Lord Jamar, Sadat X & El Da Sensei) Professional Courtesy (ft. Myka 9 of Freestyle Fellowship) Order of Magnitude (ft. Stic of Dead Prez) The Drill (ft. Twisted Insane & Ill Bill of La Coka Nostra) No Vacancy (ft. New Classic & Rakaa of Dilated Peoples) Mashitup (ft. Moka Only) Rattlesnake Pit (ft. Celph Titled) Sunny Delight (ft. Moka Only, Tonedeff & Deacon the Villain of Cunninlynguists) The Long Way Home (ft. Moka Only & Abstract Rude) Grand Finale (ft. Scarub & Sunspot Jonz of Living Legends) Emerging out of the shadows of the Sonoran Desert, Arizona MC, WISECRVCKER brings us a legendary display of boom bap talent: The Supreme Paradigm. The Grand Scheme is the first installment in WISECRVCKER's Supreme Paradigm Saga. For this album he calls upon prolific Vancouver, Canada producer, lyricist, and founding member of Swollen Members: Moka Only for instrumental production. WISECRVCKER then enlists a heavy hitting feature list including members of DeadPrez, Cunninlynguists, Brand Nubian, La Coka Nostra, Army of the Pharaohs, Dilated Peoples, Living Legends, Freestyle Fellowship, Project Blowed, and more. WISECRVCKER's freshman LP includes something for hip-hop heads of all varieties, from cool collected summer vibes alongside Abstract Rude and Moka Only, to dark and gritty verbal attacks provided by Twisted Insane and Ill Bill. The Supreme Paradigm Act I: The Grand Scheme is sure to satisfy die-hard Hip Hop Heads, and fans of multi-syllabic exhibitions.