City of Angels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Casual HE Think He #Rapgod Mp3, Flac, Wma

Casual HE Think He #Rapgod mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: HE Think He #Rapgod Country: US Released: 2011 MP3 version RAR size: 1733 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1920 mb WMA version RAR size: 1851 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 750 Other Formats: DTS DMF AC3 ASF AA VOX XM Tracklist Hide Credits #Rapgod 1 3:24 Featuring – Peplove*, Tajai Deltron Z Meets #Rapgod 2 2:23 Producer – Marv Nett Fake 3 2:31 Featuring – Izrell, Pep LoveProducer – Gully Duckets Lieza 4 3:11 Featuring – Got SamProducer – GKoop* Baseball 5 4:28 Featuring – Killer Ben*, Planet Asia, Tristate*Producer – The Elect Flamethrower 6 Featuring – Del The Funky Homosapien*Producer – Domino Written-By – J.Owens*, 2:52 T.Jones* Casual-ual 7 2:32 Producer – Rod Shields Dogon Don 8 3:18 Producer – Toure Balling Out Of Control 9 4:05 Featuring – ChappProducer – GKoop* You Ain't Gotta Lie 10 3:08 Producer – J Rawls* Credits Artwork – J-Milli-on Photography By – Stacey Debono Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year HE Think He #Rapgod (10xFile, MP3, none Casual Not On Label none US 2011 Album, 320) HE Think He #Rapgod (10xFile, ALAC, none Casual Not On Label none US 2011 Album) HE Think He #Rapgod (10xFile, ogg, none Casual Not On Label none US 2011 Album) HE Think He #Rapgod (10xFile, AAC, none Casual Not On Label none US 2011 Album) HE Think He #Rapgod (10xFile, MP3, none Casual Not On Label none US 2011 Album, Var) Related Music albums to HE Think He #Rapgod by Casual The Cherry Point & Privy Seals - Casual Sex ETA - Casual Sub Casual Drama - These Dreams Zimmermen, The - Way Too Casual SONICON - Casual Listening EP Casual Touch - Casual Touch Re-Edits Staqq Overflo - Promise We Are Scientists - Business Casual. -

Musical Theatre at the Academy

MUSICAL THEATRE AT THE ACADEMY “Cole Porter Medley” at Showcase 2019 In the Musical Theatre Department, students master storytelling in three different disciplines: voice, dance, and acting. While many graduates of The Academy attend highly regarded BFA conservatory If you are looking for a career in the arts, the programs in musical theatre or acting, training that you get here is second to none. I others choose to pursue their training can’t imagine what it would be like in a regular in academic BA programs at liberal arts high school musical theatre program. We do colleges. two to three challenging musical productions a For Musical Theatre students, performance year, in addition to a Shakespeare festival. You is a key part of learning, and students have get so much exposure to different works and ample opportunity for it. The Department techniques that by the time you are going to produces three to four mainstage college, you have the confidence to audition shows per year, including two musical productions, and several plays as part of and succeed.” the Shakespeare Festival collaboration with - Jack, Musical Theatre ‘18 the Theatre Department. In acting classes, freshman and sophomore students focus their studies on the work of Shakespeare and Thornton Wilder, while juniors concentrate on Oscar Wilde and Tennessee Williams. Seniors begin to study the work of Anton Chekhov. chicagoacademyforthearts.org 312.421.0202 MUSICAL THEATRE AT THE ACADEMY Musical Theatre Department Curriculum Musical Theatre Department students are immersed in -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

42Nd Street Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 5-25-1996 42nd Street Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "42nd Street" (1996). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 82. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/82 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42ND STREET Saturday, May 25 IP Ml" :• i fi THE CENTER FOR ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY AT GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY The Troika Organization, Music Theatre Associates, The A.C. Company, Inc., Nicholas Hovvey, Dallett Norris, Thomas J. Lydon, and Stephen B. Kane present Music by Lyrics by HARRY WARREN AL DUBIN Book by MICHAEL STEWART & MARK BRAMBLE Based on the novel by BRADFORD ROPES Original Direction and Dances by Originally Produced on Broadway by GOWER CHAMPION DAVID MERRICK Featuring ROBERT SHERIDAN REBECCA CHRISTINE KUPKA MICHELLE FELTEN MARC KESSLER KATHY HALENDA CHRISTOPHER DAUPHINEE NATALIE SLIPKO BRIANW.WEST SHAWN EMAMJOMEH MICHAEL SHILES Scenic Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by JAMES KRONZER NANZI ADZIMA MARY JO DONDLINGER Sound Design by Hair and Makeup Design by Asst. Director/Choreographer KEVIN HIGLEY JOHN JACK CURTIN LeANNE SCHINDLER Orchestral & Vocal Arranger Musical Director & Conductor STEPHEN M. BISHOP HAMPTON F. KING, JR. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket The Met played host to the Souls of Mischief during their 20-year anniversary tour of their legendary debut album, “’93 til Infinity”. This Oakland-based hip- hop group, comprised of four life-long friends, A-Plus, Tajai, Opio and Phesto, together has created one of the most influential anthems of the ‘90’s hip-hop movement: the title track of the album, ’93 ‘til Infinity. This song is a timeless classic. It has a simple, but beautifully melodic beat that works seamlessly with the song’s message of promoting peace, friendship and of course, chillin’. A perfect message to kick off a summer of music with. The crowd early on in the night was pretty thin and the supporting acts did their best to amp up the audience for the Souls of Mischief. When they took the stage at midnight, the shift in energy was astounding. They walked out on stage and the waning crowd filled the room in seconds. The group was completely unfazed by the relatively small showing and instead, connected with the crowd and how excited they were to be in Pawtucket, RI of all places. Tajai, specifically, reminisced about his youth and his precious G.I. Joes (made by Hasbro) coming from someplace called Pawtucket and how “souped” he was to finally come through. The show was a blissful ride through the group’s history, mixing classic tracks like “Cab Fare” with more recent releases, like “Tour Stories”. The four emcees seamlessly passed around the mic and to the crowd’s enjoyment, dropped a song from their well-known hip-hop super-group, Hieroglyphics, which includes the likes of Casual, Del Tha Funkee Homosapien and more. -

3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (Guest Post)*

“3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (guest post)* De La Soul For hip-hop, the late 1980’s was a tinderbox of possibility. The music had already raised its voice over tensions stemming from the “crack epidemic,” from Reagan-era politics, and an inner city community hit hard by failing policies of policing and an underfunded education system--a general energy rife with tension and desperation. From coast to coast, groundbreaking albums from Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” to N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” were expressing an unprecedented line of fire into American musical and political norms. The line was drawn and now the stage was set for an unparalleled time of creativity, righteousness and possibility in hip-hop. Enter De La Soul. De La Soul didn’t just open the door to the possibility of being different. They kicked it in. If the preceding generation took hip-hop from the park jams and revolutionary commentary to lay the foundation of a burgeoning hip-hop music industry, De La Soul was going to take that foundation and flip it. The kids on the outside who were a little different, dressed different and had a sense of humor and experimentation for days. In 1987, a trio from Long Island, NY--Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo, P.A. Pasemaster Mase and Plug Three” Mason—were classmates at Amityville Memorial High in the “black belt” enclave of Long Island were dusting off their parents’ record collections and digging into the possibilities of rhyming over breaks like the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President” all the while immersing themselves in the imperfections and dust-laden loops and interludes of early funk and soul albums. -

NSR 006 CELPH TITLED & BUCKWILD Nineteen Ninety Now CD

01. The Deal Maker 02. Out To Lunch (feat. Treach of Naughty By Nature) 03. Eraserheads (feat. Vinnie Paz of Jedi Mind Tricks) 04. F*ckmaster Sex 05. Swashbuckling (feat. Apathy, Ryu & Esoteric) 06. I Could Write A Rhyme 07. Hardcore Data 08. Mad Ammo (feat. F.T. & R.A. The Rugged Man) 09. Tingin' 10. There Will Be Blood (feat. Sadat X, Grand Puba, A.G., O.C. & Diamond) 11. Miss Those Days 12. Step Correctly 13. Wack Juice 14. Styles Ain't Raw (feat. Apathy & Chino XL) 15. Where I Are 16. Time Travels On (feat. Majik Most & Dutchmassive) Nineteen Ninety Now is finally here and a Hip Hop renaissance is about to begin! The art form is brought KEY SELLING POINTS: full-circle through this groundbreaking collaboration • Long awaited debut album from Celph Titled, who between underground giant Celph Titled and production already has gained a huge underground following as a legend Buckwild of D.I.T.C. fame! Showing that the core member of Jedi Mind Tricks' Army of the Pharaohs crew and his own trademark Demigodz releases. Also lessons from the past can be combined with the as a part of Mike Shinoda's Fort Minor project and tour, innovations of the present, these two heavyweight his fanbase has continued to grow exponentially artists have joined forces to create a neo-classic. By • Multi-platinum producer Buckwild from the legendary Diggin’ In The Crates crew (D.I.T.C.) has produced having uninhibited access to Buckwild’s original mid-90s countless classics over the last two decades for artists production, Celph Titled was able to select and record ranging from Artifacts, Organized Konfusion, and Mic to over 16 unreleased D.I.T.C. -

Interview with MO Just Say

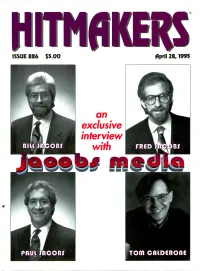

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Late Summer Opening Likely for Norfolk Light Rail Line “The Tide” Is Coming but the Question Is Though the Project Is Near Completion with When

PRST STD - U.S. POSTAGE PAID Vol. 17 No. 67 (872nd Edition) March 31 - April 6, 2011 RICHMOND, VA PERMIT NO. 639 FREE Late summer opening likely for Norfolk light rail line “The Tide” is coming but the question is though the project is near completion with when. the exception of installation and testing of Officials are maintaining that Hampton some safety and communications systems, Roads Transit (HRT) has budgeted for an Shucet refuses to reflect upon an opening August opening for the light rail line in date. Earlier this year a May opening was Norfolk, but is unclear of its start date. missed. The state’s first light rail line has According to Shucet the cause for been overwhelmed with huge cost and the initial delay was because of “safety management problems that resulted in a enhancements” originally part of the plan previous CEO retiring. The current CEO but had been deleted by the previous Philip Shucet says progress is steady, but an administration. The systems were then actual operating date can’t be determined. re-designed into the project last year. The current budget for the light rail line Shucet also points out that HRT is is $338 million—almost $106 million over incurring $17,000 in expenses on a daily the original finance plan—and has become basis because of “The Tide’s” delayed the object of two federal inquires. opening. Shucet says “The Tide” is being “I do not believe I will know a start monitored on a daily basis. date in [next month], but sometime “I’m frustrated by the delay, but I’m in May events may occur where we pleased with the day to day progress we are are more in charge of our destiny and spokesperson points out that may not be an The 7.4 mile long system extends from making,” he said. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough.