Nostalgia in Indie Folk by Claire Coleman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot |

1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com EMAIL/USERNAME PASS (FORGOT?) Email Password NEW USER? LOGIN MUSIC DEC 02, 2009, 06:07AM Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot Matt Poland [/authors/Matt%20Poland] Straight from the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina. The following audio was included in this article: The following audio was included in this article: A few years after American indie folk’s middecade spike in visibility, which, with overexposed albums including Devendra Banhart’s Rejoicing in the Hands and Joanna Newsom’s Ys, may not have been a musical zenith, the http://www.splicetoday.com/music/live-review-the-low-anthem-and-blind-pilot 1/6 1/9/2017 Live Review: The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot | www.splicetoday.com genre has settled back into an unassuming position that seems to fit the music better. The “freak folk” fringe having largely faded, the nourishing, elemental influence of Americana in all its permutations continues to generate quietly exciting new music. This was evident last week at Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro, North Carolina, during an evening of itinerant, wornin, unbeaten songs performed by The Low Anthem and Blind Pilot. Both bands make music that is melancholy but not maudlin, that is steeped in oldtime American music but not anachronistic. The Low Anthem, a Rhode Island trio, began their set with pretty unconventional instrumentation: Ben Knox Miller playing acoustic guitar and singing, Jeffrey Prystowsky on organ, and Jocie Adams playing the crotales— sort of a small xylophone made up of discs instead of planks—with a violin bow, by far the most interesting thing I’ve seen done with a violin bow since I last saw Sigur Rós. -

Indie Mixtape

Indie Mixtape :: View email as a web page :: Arcade Fire apparently is in the midst of working on a new album, with writing having “intensified” during the pandemic. In spite of ourselves, we are interested in hearing this quarantine opus, even though we openly disliked their previous album, 2017’s Everything Now. Arcade Fire is also on our brains lately because the 10th anniversary of their third ( and we would argue greatest) album, The Suburbs, was this past weekend. That album, like all Arcade Fire LPs, is a mix of breathtaking musical moments and grandiose, eyeroll-inducing thematic gestures. And yet we wouldn’t want Arcade Fire to be any other way. Sometimes they miss in embarrassing fashion, and other times they absolutely crush it. But they always swing big. For this list of our 20 favorite Arcade Fire songs, we took stock of the crushes while also attempting to understand how and why they miss. -- Steven Hyden, Uproxx Cultural Critic and author of This Isn't Happening: Radiohead's "Kid A" and the Beginning of the 21st Century PS: Was this email forwarded to you? Join our band here. In case you missed it... The first episode of our new podcast hosted by Steven Hyden and Ian Cohen is available now, wherever you listen to podcasts. Our YouTube channel now has a collection of playlists to satisfy all of your nostalgic needs. http://view.e.indiemixtape.com/...87aedf71565468329f8ac26ca254edfeee4d9b01f2c806081f3940ed3e1e6a08ac7da1357718730d50f8fc139fe23[8/6/20, 11:09:25 AM] Indie Mixtape There is an alternate universe where Phoebe Bridgers sings over trap beats. -

Am Free Here Comes the Sun

Our Paradiso is Issue No. 12 So many muses pancakes with purpose, in mother December 2019–February 2020 Bobby Alu, Dayle Larter, Seabin nature's arms, creating impact, walking and we say Project, Dumbo Feather, Bronwyn in space, a better kind of fashion it's alright Bancroft, Merryn Jean, The Calile Hotel Here comes the sun ... am free Look Touch and Feel HELLO + WELCOME WE ARE HERE THIS IS PARADISO Paradiso is so very proudly brought to you by: Enjoy reading– –8 Lila Theodoros, Publisher and Creative Director @ohbabushka Nat Woods, Editor @nat.woods_ Leana Rack, Partnership Manager @leanarack Pancakes Martin Pain, Studio Manager & Distribution Here comes @lightayurveda Alana Potts, Designer @alanapotts Chris Theodoros, Accountant With Purpose –8 and Crossword Magician the sun ... businessmatters.com.au Tania Theodoros, Proof Reader @enjoyreadingourbooks –18 I love this George Harrison song for so many reasons – In Mother Thank you to our wonderful contributors– its nostalgia, its joy, its hope. Issue 12 is an ode to hope Anna Hutchcroft Brooklyn Reardon and our vision for the future. Byron Writers Festival This year has been heavy – there is so much Chris Theodoros Nature’s arms –18 Dayle Larter despair and worry running thick in our collective Dumbo Feather Magazine consciousness; so many decisions being made out Ming Nomchong Here comes the sun ... / Dec 2019–Feb 2020 Here comes the sun ... / Dec 2019–Feb Abigael Whittaker of fear instead of love. Even as I sit here writing this, Phoebe Barrett Seabin Project –26 Lara Fells the mountain range in view of our studio is covered Paris Bluett Renee Rae in terrifying thick plumes of smoke – climate change, Holly McCauley –36 budget cuts, drought. -

COMM∆ND SMEDI∆ Inc. TORONTO

COMM∆ND S MEDI∆ iNc. TORONTO email > [email protected] telephone > +1 (604) 688-4217 w∆rnelivesey - production discography 2021 full length lp - production, mixing and engineering [except where noted] •recent work midnight oil - The Makarrata Project - new LP for release 2021 andee - lost in rewind (single) kandle - just to bring you back (single) [co-write, production, mixing] kelly heeley - EP [mixing] •less recent work midnight oil - diesel and dust - blue sky mining - redneck wonderland - capriconia - 20,000watts r.s.l the the - infected - mindbomb matthew good band - underdogs - beautiful midnight - audio of being matthew good - lights of endangered species - avalanche - white light rock n’ roll review - in a coma - chaotic neutral - i miss new wave (beautiful midnight revisited EP) - something like a storm - moving walls kim churchill - silence/win [co-songwriting/ production/ engineering/ mixing] - into the steel [string arrangements / co-production] - weight falls [co-songwriting, production 3 songs] xavier rudd - koonyum sun [mixing] email > [email protected] telephone > +1 (604) 688-4217 1 w∆rnelivesey - discography continued… julian cope - saint julian house of love - babe rainbow [co-songwriting / production] deacon blue - when the world knows your name [production / engineering] sinhead o’conner / the the - kingdom of rain (track from collaborations lp) paul young - other voices [production] jesus jones - perverse 54-40 - yes to everything - goodbye flatland [mixing] - northern soul [mixing] mark hollis - mark hollis [co-songwriting] -

Jonathan Rado Discography

Jonathan Rado Crumb | “Trophy” | Producer, Mixer Tim Heidecker | Fear of Death | Additional Production The Killers | Imploding The Mirage | Producer, Songwriter The Lemon Twigs | Songs for the General Public | Additional Production Matt Maltese | “Queen Bee”, “Madhouse”, “Leather Wearing AA” from Madhouse EP | Producer Alex Izenberg | “Caravan Château” from Caravan Château | Producer Silvertwin | “Ploy”, “Doubted”, “Promises" | Producer Purr | Like New | Producer Adam Green | Engine of Paradise | Producer Jungle Green | Runaway With Jungle Green | Producer Alex Cameron | Miami Memory | Producer Whitney | Forever Turned Around | Producer Cuco | “KeepingTabs” and “Far Away From Home” from Para Mi | Producer Tim Heidecker | What the Broken Hearted Do | Producer Jackie Cohen | Zagg | Producer, Songwriter Houndsmouth | “Talk of the Town” from California Voodoo Pt. 2 | Producer, Songwriter Foxygen | Seeing Other People | Producer, Performer, Songwriter Weyes Blood | Titanic Rising | Producer Houndsmouth | Golden Age | Producer Matt Maltese | Bad Contestant | Producer Father John Misty | God's Favorite Customer | Producer Cut Worms | Hollow Ground | Producer Alex Cameron | Forced Witness | Producer Trevor Sensor | Andy Warhol's Dream | Producer Beach Fossils | Somersault | Producer Los Angeles Police Department | Los Angeles Police Department | Producer Foxygen | Hang | Producer, Performer, Songwriter The Lemon Twigs | Do Hollywood | Producer Whitney | Light Upon The Lake | Producer Foxygen | …And Star Power | Producer, Performer, Songwriter Foxygen | We Are the 21st Century Ambassadors of Peace and Magic | Performer, Songwriter Contact: [email protected]. -

James Turrell's Skyspace Robert Dowling Life, Death

HANS HEYSEN ROBERT DOWLING ROBERT LIFE, DEATH AND MAGIC AND MAGIC LIFE, DEATH JAMES TURRELL’S SKYSPACE SKYSPACE TURRELL’S JAMES ISSUE 62 • winter 2010 artonview ISSUE 62 • WINTER 2010 NATIONAL GALLERY OF AUSTRALIA The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government Agency Issue 62, winter 2010 published quarterly by 3 Director’s foreword National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 exhibitions and displays Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au 6 Robert Dowling: Tasmanian son of Empire ISSN 1323-4552 Anne Gray Print Post Approved 10 Life, death and magic: 2000 years of Southeast Asian pp255003/00078 ancestral art © National Gallery of Australia 2010 Copyright for reproductions of artworks is Robyn Maxwell held by the artists or their estates. Apart from 16 Hans Heysen uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of artonview may be reproduced, Anne Gray transmitted or copied without the prior permission of the National Gallery of Australia. 20 Portraits from India 1850s–1950s Enquiries about permissions should be made in Anne O’Hehir writing to the Rights and Permissions Officer. 22 In the Japanese manner: Australian prints 1900–1940 The opinions expressed in artonview are not necessarily those of the editor or publisher. Emma Colton Produced the National Gallery of Australia Publishing Department: acquisitions editor Eric Meredith 26 James Turrell Skyspace designer Kristin Thomas Lucina Ward photography Eleni Kypridis, Barry Le Lievre, Brenton McGeachie, Steve Nebauer, 28 Theo van Doesburg Space-time construction #3 David Pang, -

STORM Report the STORM Report Is a Compilation of Up-And-Coming Bands and Explores the Increasingly Popular Trend Artists Who Are Worth Watching

Hungry Like The Wolf: Artists as Restauranteurs SYML Maggie Rogers Sam Bruno Angus & Julia Stone Fox Stevenson and more THE STORM ISSUE NO. 49 REPORT NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 EYE OF THE STORM Hungry Like The Wolf: Artists as Restauranteurs 5 STORM TRACKER Post Malone, Ty Dolla $ign, St. Vincent, and Courtney Barnett 6 STORM FORECAST What to look forward to this month. Holiday Season, Award Season, Rainy Day Gaming and more 7 STORM WARNING Our signature countdown of 20 buzzworthy bands and artists on our radar. 19 SOURCES & FOOTNOTES On the Cover: Marshmello. Photo courtesy of management. ABOUT A LETTER THE STORM FROM THE REPORT EDITOR STORM = STRATEGIC TRACKING OF RELEVANT MEDIA It’s almost Thanksgiving in the US, and so this special edition of the STORM report The STORM Report is a compilation of up-and-coming bands and explores the increasingly popular trend artists who are worth watching. Only those showing the most of artists and food with our featured promising potential for future commercial success make it onto our article “Hungry Like the Wolf: Artists as monthly list. Restauranteurs.” From Sammy Hagar’s Cabo Wabo to Jimmy Buffet’s Margaritaville to How do we know? Justin Timberlake’s Southern Hospitality, artists are leveraging their brand equity to Through correspondence with industry insiders and our own ravenous create extensions that are not only lucrative, media consumption, we spend our month gathering names of artists but also delicious! Featured on this month’s who are “bubbling under”. We then extensively vet this information, cover is one of our favorite STORM alumni, analyzing an artist’s print & digital media coverage, social media Marshmello (STORM #39), whose very growth, sales chart statistics, and various other checks and balances to name sounds like it would go well with ensure that our list represents the cream of the crop. -

Ishdarr Brings a Crowd,Iowa Band Speaks on Locality,Field Report To

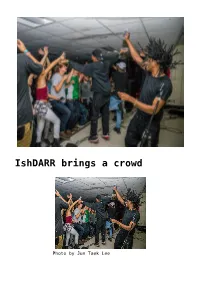

IshDARR brings a crowd Photo by Jun Taek Lee A packed crowd gathered in Gardner on Friday, Nov. 6, to hear from three young hip-hop artists—Young Eddy, Kweku Collins and IshDARR (pictured to the left). IshDARR is based out of Milwaukee, Wis. The sharp-tongued 19- year-old released a critically acclaimed album, “Old Soul, Young Spirit,” earlier this year. He largely pulled material from that album during the performance. The youthful, ecstatic energy of his recorded material transferred seamlessly to the stage. IshDARR was totally engaging for the duration of the set and did not shy away from talking with the audience, eliciting laughter and cheers. It wasn’t a terribly long set, but one that kept the people in attendance rapt from start to finish. Milwaukee is an exciting place to be an MC in 2015. The Midwestern city has recently cultivated a vibrant and dynamic DIY hip hop scene that’s only getting larger. IshDaRR, one of the youngest and most prominent members of the scene, proved on Friday night that he’s got a lot to share with the world. Assuredly, he is only getting started. Friday night was the third time that Young Eddy, aka Greg Margida ’16, has performed on campus and he is sure to have more performances next semester. Kweku Collins hails from Evanston, Ill., and this was his first time performing in Grinnell. Iowa band speaks on locality The S&B’s Concerts Correspondent Halley Freger ‘17 sat down with Pelvis’ guitarist and vocalist, Nao Demand, before his Gardner set on Friday, Oct. -

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit

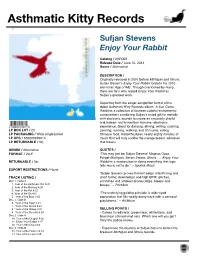

Asthmatic Kitty Records ! ! Sufjan Stevens Enjoy Your Rabbit Catalog / AKR003 Release Date / June 10, 2014 Genre / Alternative DESCRIPTION / Originally released in 2001 before Michigan and Illinois, Sufjan Steven’s Enjoy Your Rabbit foretells his 2010 electronic Age of Adz. Though overlooked by many, there are fans who regard Enjoy Your Rabbit as Sufjan’s greatest work. Departing from the singer-songwriter format of his debut Asthmatic Kitty Records album, A Sun Came, Rabbit is a collection of fourteen colorful instrumental compositions combining Sufjan’s noted gift for melody ! with electronic sounds to create an unusually playful and human- not to mention humane- electronic experience. Great for dancing, driving, writing, cooking, LP BOX LOT / 25 painting, running, walking, and of course, eating LP PACKAGING / Wide single jacket Chinese food, Rabbit features nearly eighty minutes of LP UPC / 656605919614 music that will truly soothe the savage breast, whatever LP RETURNABLE / No that means. GENRE / Alternative QUOTES / FORMAT / 2xLP “This may just be Sufjan Stevens' Magnus Opus. Forget Michigan, Seven Swans, Illinois . Enjoy Your RETURNABLE / No Rabbit is a masterclass in doing everything that logic tells music not to do.” – Sputnik Music EXPORT RESTRICTIONS / None “Sufjan Stevens proves himself adept of both long and TRACK LISTING / short forms; downtempo and high BPM; glitches, Disc 1 / Side A scratches and ambient drones; blips, bleeps and 1. Year of the Asthmatic Cat 0:24 bloops.” – Pitchfork 2. Year of the Monkey 4:20 3. Year of the Rat 8:22 4. Year of the Ox 4:01 “The underlying guiding principle is wide-eyed 5. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

God Only Knows: Historia Zespołu the Beach Boys Oraz Albumu Pet Sounds I Ich Wpływ Na Współczesną Muzykę Rozrywkową

Maciej Smółka God Only Knows: historia zespołu The Beach Boys oraz albumu Pet Sounds i ich wpływ na współczesną muzykę rozrywkową Wstęp W 1966 roku miało miejsce wiele znaczących wydarzeń dla muzyki rozrywko- wej. Spośród nich można wymienić m.in. powstanie The Jimi Hendrix Experien- ce, premierę debiutanckiego albumu Franka Zappy i The Mothers of Invention pt. Freak Out!, ostatni koncert The Beatles czy słynny wypadek motocyklowy Boba Dylana. W tym samym roku, pewnego majowego dnia stała się rzecz, która do dzisiaj kształtuje gusta muzyczne kolejnych pokoleń i odciska na nich piętno – swoją premierę miał wtedy album Pet Sounds zespołu The Beach Boys. Przez wielu zapomniany, mimo to oddziaływujący podświadomie na urozmai- canie nowych nurtów we współczesnej muzyce rozrywkowej na całym świecie. Dzisiaj uznawany za jedno z największych osiągnięć artystycznych, wtedy za niepotrzebny wybryk maszynki do tworzenia przebojów. Obecnie coraz więcej krytyków muzycznych zaczyna badać ogrom zjawiska, którym jest powszechne czerpanie wzorców z The Beach Boys, lecz charakter naukowy stanowi niewielki procent tego procederu. Widoczne inspirowanie się tym zespołem istniało już od kilku dekad, lecz stało się jeszcze bardziej po- pularne po długo oczekiwanym wydaniu w 2004 roku albumu Smile autorstwa głównego kompozytora i założyciela The Beach Boys Briana Wilsona. Płyta została wydana po 37 latach od stworzenia i przez ten okres zdążyła osiągnąć status legendarnej1. Krążek, zaraz po premierze, uzyskał ogólnoświatowe uzna- 1 J. Robinson, Beach Boys to Release Legendary ‘Smile’ Album, Ending 44 Year Wait, http:// ultimateclassicrock.com/beach-boys-smile-album-release/ (27.11.2012). 141 142 MACIEJ SMÓŁKA nie, i to pośrednio dzięki niemu świat muzyczny przypomniał sobie o istnieniu kalifornijskiego zespołu. -

Student Handbook As Well As the Home Page

Welcome to Assistance League® of Flintridge Instrumental Music! The ALF Instrumental Music program is one of the most rewarding and exciting educational opportunities offered for our students! ALF is proud to continue its support and administration of this program. We have made the change to a virtual program in light of COVID-19. With COVID restrictions and one-third of LCUSD students Virtual Learners for the year, it is unlikely there will be physical gatherings, although things are ever evolving and we will continue to re-evaluate. We thank you for your patience as we navigate new educational methods designed with the utmost safety in mind. In the following pages you will find information to help your child be successful and get the most out of being a part of the Instrumental Music program. If you still have questions about the overall program, please do not hesitate to contact us. Sincerely, Nancy Gunther, Instrumental Music Chairman 2020-2021 Joanna Petroff, Instrumental Music Assistant Chairman 2020-2021 [email protected] 818-790-2211 Message Anytime Topics 1. Music Instructors & Contact Information 2. Is the ALF Instrumental Music Program Right for your Student? 3. Instruments 4. Class Information 5. Communication & Attendance 6. Practice Expectations 7. Behavior Standards For future reference, be sure to download or bookmark this Student Handbook as well as the https://alflintridge.org/programs/instrumental-music/ home page. ® Assistance League of Flintridge Instrumental Music 2020-2021 Music Staff Michael Davis - Brass Instructor La Cañada native Michael Davis enjoys a diverse career both performing and teaching. As an orchestral musician Michael has performed with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Diego Symphony, Pasadena Symphony, Santa Barbara Symphony, Santa Barbara Opera, New West Symphony, Long Beach Symphony, WildUp, the Hyogo Performing Arts Center Orchestra, the Partch Ensemble and the Philip Glass Ensemble.