Hunting Germar Rudolf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DER SPIEGEL Jahrgang 1994 Heft 05

Werbeseite Werbeseite MNO DAS DEUTSCHE NACHRICHTEN-MAGAZIN Hausmitteilung Betr.: Wahlen, Crime a Das Super-Wahljahr ’94 fordert seine Rechte – vom Bürger, der sich durch 19 Wahlen möglicherweise überfordert sieht, von den Medien, die das Mara- thon zu werten haben. Nie war Demokratie so span- nend. Steht Deutschland erneut vor einer Wende? Wie konkurriert der Frust der Nichtwähler mit ei- ner erstaunlichen Polit-Lust, die sich im Elan neuer Bewegungen zeigt? In einer losen Folge von Artikeln analysieren SPIEGEL-Redakteure das “Feind- bild Politiker“ (Seite 36), die Mechanismen und die Schwächen der Parteiendemokratie sowie den um- worbenen großen Unbekannten des Jahres – den Wäh- ler. a Wer zöge nicht das sonnige Florida dem Niesel-Ne- bel-Nässe-Deutschland vor? Leider werden in dem Sonnenland Touristen neuerdings bevorzugt umge- bracht – so wie es einer der Hel- den des Krimi-Au- tors Carl Hiaasen empfohlen hatte, um Florida touri- stenrein zu ma- chen. Nach einem Besuch bei dem Schriftsteller, der gerade den Internationalen Deutschen Krimi- preis erhalten Polizist, Wellershoff bei Unfall-Aufnahme hat, erlebte SPIEGEL-Redakteu- rin Marianne Wellershoff Hiaasen pur: Auf dem Highway I-95 mitten in Miami rammte nächtens ein schwerer Geländewagen das Mietauto von Wellershoff und Fotografin Cindy Karp, offenkundig, um mittels Unfall einen Stopp zu erzwingen. Als Wellershoff Gas gab, tauchte der Verfolger neben dem Mietwagen auf. Die Insassinnen hörten es knallen, die Tür bekam eine erbsengroße Delle ab. Florida-Mietwagen, früher durch Kennzeichen mit Y oder Z am Anfang ausgewiesen, sind heute angeblich nicht mehr zu identifizieren. Wirklich nicht? Im Hof der Leihwa- genfirma standen nun lauter Autos mit den Buchsta- ben L und P – die Gangster werden es bemerkt ha- ben. -

Germar Rudolf's Bungled

Bungled: “DENYING THE HOLOCAUST” Bungled: “Denying the Holocaust” How Deborah Lipstadt Botched Her Attempt to Demonstrate the Growing Assault on Truth and Memory Germar Rudolf !"# !$ %&' Germar Rudolf : Bungled: “Denying the Holocaust”: How Deborah Lipstadt Botched Her Attempt to Demonstrate the Growing Assault on Truth and Memory Uckfield, East Sussex: CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS PO Box 243, Uckfield, TN22 9AW, UK 2nd edition, April 2017 ISBN10: 1-59148-177-5 (print edition) ISBN13: 978-1-59148-177-5 (print edition) Published by CASTLE HILL PUBLISHERS Manufactured worldwide © 2017 by Germar Rudolf Set in Garamond GERMAR RUDOLF· BUNGLED: “DENYING THE HOLOCAUST” 5 Table of Contents 1.Introduction ................................................................................... 7 2.Science and Pseudo-Science ...................................................... 15 2.1.What Is Science? ........................................................................... 15 2.2.What Is Pseudo-Science? ............................................................. 26 3.Motivations and ad Hominem Attacks ....................................... 27 3.1.Revisionist Motives According to Lipstadt ............................... 27 3.2.Revisionist Methods According to Lipstadt .............................. 40 3.3.Deborah Lipstadt’s Motives and Agenda .................................. 50 4.Revisionist Personalities ............................................................. 67 4.1.Maurice Bardèche ........................................................................ -

UID Jg. 19 1965 Nr. 34, Union in Deutschland

Z 6796 C BONN 26. AUGUST 1965 NR 34 • 19. JAHRGANG UNIONtnl>^utsc/üantt INFORMATIONSDIENST der Christlich Demokratischen und Christlich Sozialen Union Die Grenze zur SPD Hessische CDU kritisiert sozialdemokratischen Machtmißbrauch Eine scharfe Grenze gegenüber der SPD wurde in der letzten Landesver- ten, so verspielten sie gleichzeitig die sammlung der hessischen CDU in Wiesbaden gezogen. Auf der Rednerliste Chancen für ein Europa, das über dem standen u.a. Frau Bundesminister Dr. Schwarzhaupt, Bundestagsabgeordne- westlichen Teil des Kontinents hinaus- \x Dr. Martin und CDU-Landesvorsitzender Dr. Fay. gehe. Die SPD bezeichnete Dr. Fay als eine dem Traditionalismus verhaftete Die Erhaltung der Freundschaft mit den Aus diesen und aus wirtschaftlichen Partei, die keine neuen Ideen habe und USA, die Weiterentwicklung der Freund- Gründen sei der Sozialismus nicht zu ge- sich in einem noch immer nicht vollzoge- schaft mit Frankreich und den Ausbau brauchen, meinte Dr. Martin. Erst der nen Prozeß der Umstellung um eine der kulturellen und wirtschaftlichen Be- kulturelle Einfluß und die Wirtschafts- „künstliche Modernität" bemühe. Dies ziehungen zu Osteuropa bezeichnete die kraft hätten es der Bundesrepublik er- wundere nicht, da die Grundeinstellung Spitzenkandidatin der hessischen CDU- möglicht, in Ländern des Ostblocks prä- der SPD auf dem „Phylosophischen Pessi- Landesliste, Frau Bundesminister Dr. sent zu werden, ohne in der Deutschen mismus" basiere. Die heutige SPD ist Schwarzhaupt, auf der Landesversamm- Frage Konzessionen eingehen zu müssen. nach Ansicht von Dr. Fay zu sehr nach lung der CDU Hessen in Wiesbaden als Dieser Weg müsse weiter beschriften den Erfordernissen der Massenpsycholo- Kernstücke der deutschen Außen- und werden. gie ausgerichtet, als daß man ihr und Sicherheitspolitik in der Sozialpolitik ihren Führern vertrauen könne. -

Smith's Report, No

SMITH’S REPORT On the Holocaust Controversy No. 146 www.Codoh.com January 2008 Challenging the Holocaust Taboo Since 1990 THE MAN WHO SAW HIS OWN LIVER Introduction: Death and Taxes Richard “Chip” Smith Nine Banded Books is a new publishing house that has chosen to make my manu- script, The Man Who Saw His Own Liver, its first publication, which is an honor I very much appreciate. Chip Smith is the head honcho there and has done everything right, be- ginning with the imaginative idea of transposing the format of my one-character play, The Man Who Stopped Paying, into that of a short novel, The Man Who Saw His Own Liver. Not one word has been changed. It has been formatted in a simple, unique, and imaginative way, and is followed by a coda that, again, is an imaginative choice that never would have occurred to me. The Man Who Saw His Own Liver is at the printer now and we expect to have it to hand the first week in February. Following is the elegant and rather brilliant introduction written by the publisher. radley Smith is one of those writers. Like Hunter Thompson or Hubert Selby; like B Brautigan, Bukowski, or the Beats. You read him when you’re young. You read him with a rush of discovery never to be forgotten. The prose is clean and relaxed and punctuated with a distinct, tumbling, rhythmic flair. It goes down easy. It makes you want to write. The world Smith made is suffused with a restless vitality that feels personal and true. -

Deborah Lipstadt Blasts 'Holocaust-Abuse' by U.S., Israeli Politicians

No. 188 Challenging the Holocaust Taboo Since 1990 January 2012 Online at www.codoh.com Deborah Lipstadt Blasts 'Holocaust-abuse' by U.S., Israeli Politicians Jett Rucker his Holocaust revisionist letter, Lipstadt was fully kitted out As her erstwhile accuser was has a confession to make, in horns and a tail. apprehended and imprisoned in T and it’s worse than any- As the jackals closed in to pick Austria for doing the very sort of thing to which Bradley Smith con- Irving’s figurative bones (the ver- thing Lipstadt publicly accused him fessed in his best-selling (?) Con- dict ruined him financially, if not of doing, she came out foursquare fessions of a Holocaust Revisionist: otherwise), our new celebrity Deb- as “a free-speech person,” and with I have become a grudging admirer orah Lipstadt began to show that impeccable logic, she objected to of Deborah Lipstadt. Yes, the Deb- his being punished in any (crimi- orah Lipstadt who in 2001 with the nal) way for his speech. able assistance of her publisher Studying the matter, I immedi- Penguin-Putnam defended success- ately dismissed all imaginings that fully against the libel suit brought Lipstadt was influenced by remorse before the Queen’s Bench by the over Irving’s partly self-inflicted embattled David Irving. Lipstadt fate and concluded that she really had labeled Irving a “Holocaust did believe in Open Debate, includ- denier” in her 1993 book about ing of the Holocaust! I conceived “Holocaust denial.” The book sold admiration for this position, so un- adequately before the trial, and mistakably demonstrated by this considerably better during and after particular famous person—their Deborah Lipstadt it. -

Verzeichnis Der Adelmannschen Bibliothek Schriften Aus Dem Nachlass Von Dieter Adelmann

Universität Potsdam Die Arbeitsbibliothek von Dieter Adelmann befindet sich in der Universi- Andreas Kennecke (Hrsg.) tätsbibliothek Potsdam und ist in diesem Band verzeichnet; der Nachlass und das Findbuch befinden sich im Universitätsarchiv Potsdam. Dieter Adelmann wurde am 1. Februar 1936 in Eisenach, Thüringen, geboren. Er Verzeichnis der studierte Philosophie, Germanistik und Soziologie an der Freien Universi- tät Berlin und an der Universität Heidelberg und wurde dort 1968 mit der Adelmannschen Bibliothek Arbeit Einheit des Bewusstseins als Grundlage der Philosophie Hermann Cohens bei Dieter Henrich und Hans-Georg Gadamer promoviert. Von 1968 bis 1970 war Adelmann Leiter des „Collegium Academicum“ der Universität Heidelberg; von 1970 bis 1974 Landesgeschäftsführer der SPD in Baden-Württemberg (Zuständigkeit: Politische Planung) und zeitweise auch Wahlkreisassistent des SPD-Bundestagsabgeordneten Horst Ehmke. Anschließend arbeitete Adelmann publizistisch mit dem Grafiker und gegenwärtigen Präsidenten der Berliner Akademie der Künste, Klaus Staeck zusammen, bevor er von Juli 1977 bis einschließlich September 1979 beim Vorwärts im Ressort Parteien und Programme beschäftigt war. Nach seinem Abschied vom Vorwärts war Adelmann freiberuflich in Bonn tätig, u.a. als Journalist. 1995 war er wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter im Rahmen der Herausgabe der Werke Hermann Cohens am „Moses- Mendelssohn-Zentrum“ und am Lehrstuhl für Innenraumgestaltung an der Technischen Universität Dresden. Nach dem Ende der Tätigkeit in Potsdam war Adelmann bis zu seinem Tod am 30. September 2008 freiberuflicher Philosoph und Cohen-Forscher. ISBN 978-3-86956-298-8 Bibliothek der Adelmannschen (Hrsg.) | Verzeichnis Andreas Kennecke Universitätsverlag Potsdam Andreas Kennecke (Hrsg.) Verzeichnis der Adelmannschen Bibliothek Schriften aus dem Nachlass von Dieter Adelmann Hrsg.: Görge K. Hasselhoff Band 3 Verzeichnis der Adelmannschen Bibliothek Andreas Kennecke (Hrsg.) Verzeichnis der Adelmannschen Bibliothek Mit einem Vorwort von Andreas Kennecke und einer Einleitung von Görge K. -

Auschwitz Biplanes Were Handily Dealt with by the MAKE THIS BOOK a REALITY

BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY FROM THE BARNES REVIEW! The Barnes Review A JOURNAL OF POLITICALLY INCORRECT HISTORY VOLUME XXIV NUMBER 2 MARCH/APRIL 2018 WWW.BARNESREVIEW.COM MUSSOLINI’SVOLUME 1: THE TRIUMPHANT WAR YEARS mong the great misconcep- ture. They shine new light, for example, tions of modern times is the on the impressive successes of Italy’s mil- assumption that Benito Mus- itary on the sea, in the air and on land. solini was Adolf Hitler’s junior Contrary to popular mainstream portray- partner, who made no sig- als, Italy’s military was a superior fighting The Anificant contributions to the Axis effort force. in World War II. That conclusion These and numerous other dis- originated with Allied propagan- closures combine to debunk lin- dists determined to boost An- gering propaganda stereo- glo-American morale, while types of an inept, ineffectual undermining Axis cooper- NEW Italian armed forces and ation. FROM their allegedly inept com- Chemistry The Duce’s failings, real manders and supreme or imagined, were inflated leader. That dated por- and ridiculed; his successes TBR trayal is rendered obsolete pointedly demeaned or ig- by a true-to-life account of of nored. Italy’s bungling navy, in- the men and weapons of Mus- effectual army—as cowardly as it was solini’s War: Volume I—The Tri- ill-equipped—and air force of antiquated umphant Years. Auschwitz biplanes were handily dealt with by the MAKE THIS BOOK A REALITY . Western Allies. So effective was this disin- formation campaign that it became post- Make your donation to TBR’s publish- war history, and is still generally taken for ing efforts today and get your copy of this granted, even by otherwise well-informed groundbreaking work of Revisionist his- scholars and students of World War II. -

Wir Stellen Uns Vor

Wir stellen uns vor Mitmachen. Mitgestalten. Landsmannschaft Landsmannschaft Bund Bessarabiendeutscher Landsmannschaft der Oberschlesier der Banater Schwaben der Danziger Verein der Buchenland deutschen Landsmannschaft Verband Landsmannschaft Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft Ostpreußen der Siebenbürger der Deutschen Landsmannschaft der Donauschwaben Sachsen aus Russland Landsmannschaft Karpatendeutsche Landsmannschaft Landsmannschaft Pommersche Westpreußen Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Litauen Weichsel-Warthe Landsmannschaft Landsmannschaft Landsmannschaft Landsmannschaft Deutsch-Baltische Landsmannschaft Ostbrandenburg/ der Deutschen aus Ungarn der Sathmarer Gesellschaft Schlesien Neumark Schwaben OST- UND MITTELDEUTSCHE VEREINIGUNG UNION DER VERTRIEBENEN UND FLÜCHTLINGE DER CDU/CSU Wir stellen uns vor | Mitmachen. Mitgestalten. Wir stellen uns vor | Mitmachen. Mitgestalten. Machen Sie mit! Grundsätze der Vertriebenen- Die Ost- und Mitteldeutsche Vereinigung und Aussiedlerpolitik der OMV der CDU/CSU (OMV) ist Partner und Anwalt der deutschen Heimatvertriebenen, Die OMV tritt ein für das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker und im Flüchtlinge, Aussiedler und Spätaussiedler. Rahmen dessen für ein internationales Volksgruppen- und Minderheiten- recht, das Recht auf die Heimat, eigene Sprache und Kultur. Völkerver Wir wollen gemeinsam mit den deutschen treibungen jeder Art müssen international geächtet und verletzte Rechte Heimatvertriebenen ein Europa der anerkannt werden. Gerechtigkeit und historischen Wahrheit schaffen. Darum werden -

Die Protokolle Des CDU-Bundesvorstands 1969-1973

13 Düsseldorf, Samstag 24. Januar 1971 Sprecher: Barzel, [Brauksiepe], Schröder. Vorbereitung des Bundesparteitags. Bericht Dr. Gerhard Schröders über seine Moskau-Rei- se. Bericht Dr. Rainer Barzels über seine Warschau-Reise. Beginn: 14.00 Uhr Ende: 16.00 Uhr Vorbereitung des Bundesparteitags Der Bundesvorstand nimmt die Vorschläge des Präsidiums für die personelle Be- setzung des Parteitagspräsidiums und der Antragskommission sowie den Vorschlag des Zeitplans für die Programmdiskussion einstimmig an. Auf Anregung von Frau Brauksiepe wird in das Parteitagspräsidium zusätzlich Frau Pieser aufgenommen. Vorschläge des Präsidiums (Sitzung am 20. Januar 1971) an den Bundesvorstand für den Ablauf des 18. Bundesparteitages 25.–27. Januar 1971 in Düsseldorf 1. Präsidium des Parteitages: Präsident: Heinrich Köppler; Stellvertreter: Frau Becker-Döring1; Mitglieder: Dr. Alfred Dregger, Dr. Georg Gölter2, Wilfried Hasselmann, Peter Lorenz, Adolf Müller (Remscheid), Heinrich Windelen, Dr. Manfred Wörner. 2. Mitglieder der Antragskommission: Vorsitzender: Dr. Bruno Heck; Stellvertreter: Dr. Rüdiger Göb; Mitglieder: Ernst Benda, Irma Blohm, Professor Dr. Walter Braun, Bernhard Brinkert3, Professor Dr. Fritz Burgbacher, Jürgen Echternach, Dr. Heinrich Geißler, Dr. Baptist Gradl, Frau Griesinger, Leisler Kiep, Dr. Konrad Kraske, Egon Lampersbach, Gerd Langguth4, 1 Dr. Ilse Becker-Döring (1912–2004), Rechtsanwältin und Notarin; 1966–1972 Erste Bürger- meisterin in Braunschweig (CDU), 1970–1978 MdL Niedersachsen. Vgl. Protokolle 5 S. 177 Anm. 7. 2 Dr. Georg Gölter (geb. 1938), Gymnasiallehrer; 1958 JU, 1965–1971 Landesvorsitzender der JU Rheinland Pfalz, 1967–1969 Referent für Grundsatzfragen im Büro von Kultusminister Bernhard Vogel, 1968–1977 Vorsitzender des KV Speyer, 1969–1977 MdB, 1975–1979 Vor- sitzender des BV Rheinhessen-Pfalz, 1977–1979 Minister für Soziales, Gesundheit und Sport, 1979–1981 für Soziales, Gesundheit und Umwelt, 1981–1991 für Kultus, 1979–2006 MdL Rheinland-Pfalz. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis

INHALTSVERZEICHNIS MENSCHEN Die Entwicklung der Menschheit Erich Kästner 8 Mensch Meyers Standard Lexikon 8 Der Mensch Matthias Claudius 10 Stufen Hermann Hesse 10 * Das Wort Mensch Johannes Bobrowski 11 Kaspar Reinhard Mey 12 Wenn Herr K. einen Menschen liebte Bertolt Brecht 13 Du sollst dir kein Bildnis machen Max Frisch 13 * Ich bin Jude Ernst Toller 14 Der andorranische Jude Max Frisch 15 Gefühle Urs Widmer 16 Ich darf dich nicht lieben Hedwig Courths-Mahler 18 Der Wolf und das Lamm Phädrus 19 Der Wolf und das Schaf G. E. Lessing 19 Die Maus Phädrus 19 Kleine Fabel Franz Kafka 19 Der Struwwelpeter H. Hoffmann 20 Der Anti-Struwwelpeter F. K. Waechter 20 Steckbrief 21 Sterntaler Brüder Grimm 21 Großmutters Märchen Georg Büchner 22 Kinder Bettina Wegner 22 Fenster-Theater Ilse Aichinger 23 Brudermord im Altwasser Georg Britting 26 Die ungezählte Geliebte Heinrich Böll 27 San Salvador Peter Bichsel 29 Alleinsein und Partnerschaft Peter Handke 31 Der Einsame Wilhelm Busch 32 Mann und Frau heute Zeitungsbericht 33 Über die Liebe Bertolt Brecht 34 Zwei Männer Günter Weisenborn 35 Die Worte des Glaubens Friedrich Schiller 37 * Das Lied von der Unzulänglichkeit menschlichen Strebens Bertolt Brecht 38 SPRACHE Sprache als Gebärde Vier Fotos 39 Das Wunder der Sprache Walter Porzig 42. * Meine Sprache Günter Kunert 44 Ein Tisch ist ein Tisch Peter Bichsel 44 § 1 der Straßenverkehrsordnung Jürgen von Manger 47 Kleinstadtsonntag Wolf Biermann 47 Drei Mann in einem Boot Jerome K. Jerome 48 Bundestagsrede Loriot 49 Die Zeitung Heinrich Böll 50 * Reklame -

Holocaust Revisionism

Holocaust Revisionism by Mark R. Elsis This article is dedicated to everyone before me who has been ostracized, vilified, reticulated, set up, threatened, lost their jobs, bankrupted, beaten up, fire bombed, imprisoned and killed for standing up and telling the truth on this historical subject. This is also dedicated to a true humanitarian for the people of Palestine who was savagely beaten and hung by the cowardly agents of the Mossad. Vittorio Arrigoni (February 4, 1975 - April 15, 2011) Holocaust Revisionism has two main parts. The first is an overview of information to help explain whom the Jews are and the death and carnage that they have inflicted on the Gentiles throughout history. The second part consists of 50 in-depth sections of evidence dealing with and repudiating every major facet of the Jewish "Holocaust " myth. History Of The Jews 50 Sections Of Evidence "You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, not holding to the truth, for there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies." Jesus Christ (assassinated after calling the Jews money changers) Speaking to the Jews in the Gospel of St. John, 8:44 I well know that this is the third rail of all third rail topics to discuss or write about, so before anyone takes this piece the wrong way, please fully hear me out. Thank you very much for reading this article and for keeping an open mind on this most taboo issue. -

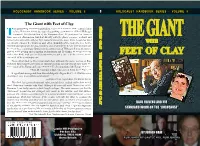

Feet of Clay of Ffeet O Holocaust Handbook Series Series Handbook Hholocaust

HHOLOCAUSTOLOCAUST HHANDBOOKANDBOOK SSERIESERIES ∙ VOLUMEVOLUME 3 3 HHOLOCAUSTOLOCAUST HHANDBOOKANDBOOK SSERIESERIES ∙ VVOLUMEOLUME 3 The Giant with Feet of Clay JÜRGEN GRAF J JÜRGEN GRAF his outstanding short study provides a merciiless demolition of theh central claims Ü R of the Holocaust theh sis byy way of a prp obbinng exammination of Raua l Hilberg’s G canoonical The DeD sts rur ction of the European Jews. By narrowing hisi focus to E those paages in Destrur ction that deal directly with the plans, pror grram, method, and N G TTHEHE GGIANTIANT numerical results of the alleged Nazi mass murder of the Jews, Swisss reseaarcher Graf relentlessly expx oso es the weakness and, often, absurdity of the best evidence for the R WWITHITH extermination prograr m, the gas chambers, and anything like the six millil on deaath tolo l. A F Giant can be devastatingly funny in its deconstruction of Hilberg’s fl imsyy attempts tot ∙ THE GIANT WITH FEET OF CLAY OF WITH FEET THE GIANT portray mass gasssing and cremation at Auschwitz and Treblinka; its foco usedd brevity T makes thhis book both an excellent introduction and a fi ne refresher course on the H FFEETEET OOFF CCLAYLAY essentiai ls of the revisionist case. E “Jürü gen Graf fi nds in the present study that, although the major portion of Raul G I Hilbere g’s bench-mark work rests on reliable sources, its title should haave been The A Persece ution of the European Jews rather than The Destruction of the Europpeaan Jews.” N T —Prof. Dr. Costa Zaverdinos, University of Natal, Soutu h AfA rica, rtd.