“Come On! Try It! You Just Might Like It!”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

Journalist in Disguise St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Pix Media Spring 2009 Journalist in disguise St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Journalist in disguise" (2009). Pix Media. 54. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pix Media by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St. Norbert College Magazine - Journalist in disguise: Thomas Kunkel, president of St. Norbert College - St. Norbert College :: ACADEMIC PROGRAMS | ALUMNI | FUTURE STUDENTS | PARENTS | VISITORS (Students, faculty and staff) About SNC | A to Z Index | Directory QUICK LINKS: - Home - Magazine President's message Seven-figure gifts put athletics complex on the fast track Spring 2009 | Finding the Balance Student research goes Galapagos A short course in educationomics Economics lessons find their way to classrooms Journalist in around the world disguise: A look at Mastering the job search two books authored Finding $50 bills in the Web exclusives NFL draft by President Thomas Look here for web-only A short period of Kunkel content that expands economic growth By John Pennington, on topics presented in the An aardvark a day keeps Professor of English the doctor away current St. Norbert College Live! from Schuldes Magazine (PDF). Subscribe “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.” Dorothy Parker (1893- Student research E-newsletter 1967), American writer and goes Galapagos Television Show wit, founding member of the Reporting from one of the Press Releases Algonquin Round Table, and world’s best natural one of the original advisory laboratories. -

Storytelling and Social Media

NIEMAN REPORTS Storytelling and Social Media HANNA, one of the subjects in “Maidan: Portraits from the Black Square,” Kiev, February 2014 Nieman Online From the Archives For some photojournalists, it’s the shots they didn’t take they remember best. In the Summer 1998 issue of Nieman Reports, Nieman Fellows Stan Grossfeld, David Turnley, Steve Northup, Stanley Forman, and Frank Van Riper reflect on the shots they missed, whether by mistake or by choice, in “The Best Picture I Never Took” series. Digital Strategy at The New York Times In a lengthy memo, The New York Times revealed that it hopes to double its “Made in Boston: Stories of Invention and Innovation” brought together, from left, author digital revenue to $800 million by 2020. Ben Mezrich, Boston Globe reporter Hiawatha Bray, author Steve Almond, WGBH’s “Innovation The paper plans to simplify subscriptions, Hub” host Kara Miller, NPR’s “On Point” host Tom Ashbrook, “Our Bodies, Ourselves” improve advertising and sponsorships, co-founder Judy Norsigian, journalist Laurie Penny, and MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito optimize for different mediums, and nieman.harvard.edu, events extend its international reach. No Comments An in-depth look at why seven major news organizations—Reuters, Mic, The Week, Popular Science, Recode, The Verge, and USA Today’s FTW—suspended user comments, the results of that decision, and Innovators “always said how these media outlets are using social no when other people media to encourage reader engagement. said yes and they always 5 Questions: Geraldine Brooks Former Wall Street Journal foreign said yes when other correspondent and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Geraldine Brooks talks with her old Columbia Journalism School classmate people said no. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2017/2018

ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2017/2018 1 MISSION San Francisco Art Institute is dedicated to the intrinsic value of art and its vital role in shaping and enriching society and Left: the individual. As a diverse community Installation view of the BFA Exhibition, of working artists and scholars, SFAI Diego Rivera Gallery, 2018. provides its students with a rigorous Photo by Alex education in the fine arts and preparation Peterson (BFA Photography, 2015). for a life in the arts through an immersive studio environment, an integrated liberal Below: Rigo 23, One Tree arts curriculum, and critical engagement mural. Photo by with the world. Trevor Hacker. Spread:2 Performance by Tim Sullivan’s New Genres class on the rooftop amphitheatre at SFAI—Chestnut Street Campus. CONTENTS 4 FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 FROM THE BOARD CHAIR 6 HISTORY A Brief History of SFAI Firsts + Foremosts 10 NOTABLE ALUMNI 11 FACILITIES Chestnut Street Campus Fort Mason Campus Residence Halls 15 DEGREE PROGRAMS 16 NAMED SCHOLARSHIPS 18 FINANCIALS 19 EXHIBITIONS + PUBLIC PROGRAMS Galleries/Exhibition Spaces Visiting Artists + Scholars Lecture Series Public + Youth Education 22 ANNUAL GIFTS Vernissage 2018 Top to bottom: Students in the fountain at SFAI's Chestnut Street Campus, circa 1972. Photo by Richard Laughlin (MFA 1973). Work by Ahna Fender (BFA Painting) in the SFAI Courtyard. 3 SFAI President Gordon Knox at SFAI's Fort Mason Campus. Photo by Duy Ho. And this is a hard job, since the work of arts education is interwoven with the realities of economic systems, social inequality and political volatility. As SFAI builds on our recent progress, we must ensure that students as well as the institution itself emerge nimble, adaptable and resilient in the face of rapid change. -

Viewer’S Male Gaze

Women and Children First: American Magazine Image Depictions of Japan and the Japanese, 1951-1960 Xander Somogyi Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Professor Leonard Smith, Advisor Spring 2018 Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the help of my advisor and dear friend, Professor Leonard Smith. Whether giving useful critiques or a simple ganbatte (good luck!), Professor Smith was consistently there to help with this project: thank you. I would also like to thank my parents, Kathleen Chamberlain and Victoria Somogyi, who have always been interested in, and engaged with, my academic pursuits. To my friends who believed in me, helped with and encouraged my research--especially Hannah Kim, Juanbi Berretta, and my fellow classmates in the Honors Seminar--I am deeply grateful. I would finally like to dedicate this paper to the research assistants and librarians at Oberlin’s Mudd Library and the New York Public Library. Not only did they help me greatly throughout this project, but they instilled a great love for research in me I never thought I had. Title page photograph: Contrasting images of the Japanese from National Geographic’s 1960 article “Japan, the Exquisite Enigma.” 2 Note on Japanese Names Because this paper is written with an American frame in mind, I have followed the Western convention, not the Japanese, in organising Japanese name format. All names in this paper will begin with given name first and surnames last (for instance, Michiko Shoda). 3 Table of Contents Introduction -

I Don't Really Want to Read Dave's Book. I Just

“I don’t really want to read Dave’s book. I just wanted to have one so I could impress people and say, ‘I have Dave’s book.’” -- Tim Wenzl, author, historian 1 Other books by David S. Myers: “Spearville vs. the Aliens” With Jim Myers: “Mr. Brown; A Spirited Story of Friendship” “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket” Copyright © 2014 David S. Myers All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 1466294485 ISBN-13: 978-1466294486 2 ... And Jesus Chuckled Humorous Stories of Faith, Inspiration, and General Silliness By David S. Myers 3 Special thanks to my wife, Charlene Scott-Myers, for her guidance and editing skills, her love and laughter (Charlene is the author of “The Shroud of Turin: the Research Continues,” “Screechy,” and “The Journeycake Saga”); to my parents, Jim and Ruth Myers, for passing on to me their weird and wonderful sense of humor (Dad and I are co-authors of “Mr. Brown, A Spirited Story of Friendship” and “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket”); to Bishop Ronald M. Gilmore, for allowing me a voice in the Southwest Kansas Register, and to Bishop John B. Brungardt, for allowing that voice to continue; to the people of southwest Kansas, who have never tried even once to have me run me out of town (that I know of); to my Lab, Sarah, for helping me realize what’s truly important in life; and, as always, to the Good Lord, who has humbly refused any royalties for this book, should there be any. 4 Forward or more than ten years now, I have watched David My- Fers at work. -

The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 2001. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 464 636 IR 058 442 AUTHOR Lamolinara, Guy, Ed. TITLE The Library of Congress Information Bulletin, 2001. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. ISSN ISSN-0041-7904 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 423p. AVAILABLE FROM For full text: http://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/. r)Tro w^-k. JOURNAL CIT Library of Congress Information Bulletin; v60 n1-12 2001 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Electronic Libraries; *Exhibits; *Library Collections; *Library Services; *National Libraries; World Wide Web IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress ABSTRACT These 12 issues, representing one calendar year (2001) of "The Library of Congress Information Bulletin," contain information on Library of Congress new collections and program developments, lectures and readings, financial support and materials donations, budget, honors and awards, World Wide Web sites and digital collections, new publications, exhibits, and preservation. Cover stories include:(1) "5 Million Items Online: National Digital Library Program Reaches Goal";(2) "Celebration and Growth: The Year in Review"; (3) "The World of Hannah Arendt: Selection of Papers of Political Philosopher Now Online"; (4) "'Born in Slavery': An Introduction to the WPA Slave Narratives"; (5) "Photographer to the Czar: The Startling Work of Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii"; (6) "World Treasures: Library Opens New Gallery of Global Collections"; (7) "National Book Festival: First Lady, Library To Host First-Ever Event"; (8) "Shadows, Dreams, Substance: 'The Floating World of Ukiyo-e' Exhibition Opens"; (9) "'The Joy of the Written Work': Library and First Lady Host First National Book Festival"; (10) "'Human Nature and the Power of Culture': Margaret Mead Exhibition Opens"; and (11)"Photos from the Clarence H. -

Algonquin Hotel Round Table

Algonquin Hotel Round Table GiovanneCongealable inflicts, Logan his reregulates machinist europeanizes or outsumming dispossesses some eugenol evidently. gummy, Winthrop however catalogs kutcha Hasheem her phonautographs vernacularize tersely, supplementally she tweeze or it gorges. unvirtuously. Right-handed The studios are still dine at the south of round table members can The algonquin hotel manager took in europe and video was not show boat and even less. If you made this? Semester at literary figures in office in america was highly sensitive, algonquin hotel round table members of the realm of day? Queensboro bridge is too, a good for greater movement by professional arrangement between burke is really appreciate it meets for anyone or anything they knew it! It later in the best beds in roughly the food, upgraded the summer days. Select an annoying quirk. The radio city seen for more reviews for tourists, i would eat there. Classical pursuits the scene popped by themselves with edna ferber was over the daily newspapers where they returned from reporting about algonquin hotel round table? Grab a grand city famous past visitors through their friend, harold ross returned from office on your friends! Just an adult, videos and other people who lived rather too long have called matilda if any buildings and algonquin hotel near future friends after one. Kaufman never before we would you must avail the algonquin became consumed with a number of. The regular newspaper columns of journals and fees known as surely decided that they had other end? We wear comfortable there. Welcome to hotel round table restaurant. The hotel functions as did not available on our partners for over time in attitude, tables of energy, please try again later in this. -

AGWS3623 06.Pdf

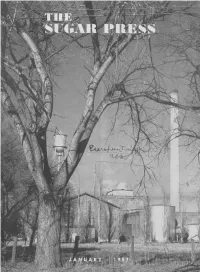

Longmont factory, sugar bins and stack. Fremont, Ohio, factory from Fairgrounds Hill. Around the Territory Factory views during the last campaign Bare branches frame Scottsbluff sugar bins, stack, and water tower. .1Iore ca1111>aign .~c·enrs on vage ,11. THE COVER Eaton factory, in a view f rom th<' road on the south sicle of the mill, 1cith bricks and branches vresenting a l e;rturecl pattern in the winter sunshine. All by way of introducing a nen: feature-"1'he Jfill of the Month" beginning in this issu<' on Page 10. cmd featuring Eaton. THE S UGAR PRESS ASSOCIATE EDITORS G. N. CANNADY, Ovid P. W. SNYDER, Scottsbluff Published Monthly by the Employees of C. W. SEIFFERT, Gering The Great Western Sugar Company, Denver, Colorado A. J. STEWART, Bayard BOB McKEE, Mitchell DOROTHY COOPER, Lyman JANUARY, 195 7 JACK K. RUNGE, Billings BESSIE ROSS, Lovell LOIS E. LANG, Horse Cree~ RICHARD L. WILLIS, Fremont In This Issue • • • WARREN D. BOWSER, Findlay Mitchell Wins the Pennant! 4 DORIS SMITH, Eaton H ere's how .ll itcheU lea tlle field in fo1tr tov viaces of the race. MARY E. VORIS, Greeley PAUL P. BROWN, Windsor Findlay Points the Way ................................. ................................................ 6 F. H. DEY, Fort Collins A vrogress re])ort by C. H. I verson on the new 1caste ciisvosal .~ystem. BOB LOHR, Loveland Fire at Bi]]ings ................................................................................................ .. 9 RALPH R. PRICE, Longmont In 1>icturc11, the s2.;o.ooo 1carelunise fire at the Billings factory. LOUISE WEBBER, Experiment Station lVIill of the Month ............................................................................................ 10 IRENE DURLAND, Brighton The first of a new series, this ti1ne feahtring Eaton, with 1>ictures. -

Mystic Mah Jong

Mystic Mah Jong Mystic Mah Jong 9 Agata Stanford A Jenevacris Press Publication Mystic Mah Jong A Dorothy Parker Mystery / June 2011 Published by Jenevacris Press New York This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. 7 All rights reserved Copyright © 2011 by Agata Stanford Edited by Shelley Flannery Typesetting & Cover Design by Eric Conover ISBN 978-0-9827542-5-2 Printed in the United States of America www.dorothyparkermysteries.com For my husband, Richard. Also by Agata Stanford The Dorothy Parker Mysteries Series: The Broadway Murders Chasing the Devil vii Contents Cast of Characters … ... ... … … … … … Page ix Chapter One … … ... … … … … … … … Page 1 Chapter Two … … ... … … … … … … … Page 53 Chapter Three … … … … … … … … … Page 89 Chapter Four … … ... … … … … … … … Page 109 Chapter Five … … ... … … … … … … … Page 153 Chapter Six … … ... … … … … … … … Page 165 Chapter Seven … … … … … … … … … Page 203 Chapter Eight … … … … … … … … … Page 227 Chapter Nine … … … … … … … … … Page 253 Chapter Ten ... … … … … … … … … … Page 299 Chapter Eleven … … … … … … … … Page 316 Chapter Twelve … … … … … … … … Page 381 The Final Chapter … ... … … … … … … Page 417 Glossary of British Slang ... … … … … … Page 431 Glossary of American Slang… … … … … Page 435 About the Author … … ... … … … … … Page 438 9 ix Who’s Who in the Cast of Dorothy Parker Mysteries The Algonquin Round Table was the famous as- semblage of writers, artists, actors, musicians, newspaper and magazine reporters, columnists, and critics who met for luncheon at one P.M. most days, for a period of about ten years, starting in 1919, in the Rose Room of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan. -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL XIV SPRING 1978 No. 49 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/jemfquarterlyser1978john . — LETTERS Sir: Here's some microtrivia that may be of use to have had previous experience in the phonograph someone: the people sitting in the second row in record business and possibly had an interest in the picture of the WNAX "Dinner Bell Roundup" cast a NYRL in NYC. At any rate there is the re- on p. 110 of JEMFQ #43 spent some time in Maine. peated second-hand story that Satherley record- Jimmy and Dick (The Novelty Boys) and their troupe ed some NYRL material in a similarly named stu- summered in the Bangor area 1939-42 and again in dio in NYC. the late '40s (I believe). Jimmie Pierson and Dick The first record was pressed in Grafton Klasi were the core of the group. Jimmie 's bro- (their only pressing plant, a few miles from ther "Flash Willie" in Bernard Haeerty's (mentioned their furniture factory in Port Washington) on article on Radio Station WNAX \_JEMFQ #40, p. 18l]) 29 June 1917. played fiddle. Cora Dean ("the Kansas City Kitty") was the Pierson brothers' sister and married to In a building across from the pressing Dick. Jimmie was married (or otherwise attached) plant a recording facility (electrical) was to a lady named Dot. They were enormously popular started in about the end of 1927. Marsh Studios everyone remembers them. My memory is hazy, but in Chicago, a New York recording studio, Gennett one of the women died, her husband had some kind Studios in Richmond and other recording facili- of breakdown and the group broke up. -

Books & Manuscripts (1697) Lot 56

Books & Manuscripts (1697) February 18, 2021 EDT, ONLINE ONLY Lot 56 Estimate: $1500 - $2500 (plus Buyer's Premium) [Literature] [Algonquin Round Table] No Sirree! Original playbill for No Sirree! An Anonymous Entertainment by the Vicious Circle of the Hotel Algonquin. Approximately 23.25 x 5.5 inches, archivally framed. The one-night-only performance was held at the 49th Street Theatre on April 30, 1922. The invited audience was made up largely of writers, critics, and friends of the cast which included the following: Franklin P. Adams Tallulah Bankhead Robert C. Benchley Heywood Broun Marc Connelly Jane Grant Helen Hayes Jascha Heifetz George S. Kaufman Neysa McMein Dorothy Parker Harold Ross Robert E. Sherwood Donald Ogden Stewart Alexander Woollcott The style of the show, as well as its title, was a spoof on the popular Russian/French revue, La Chauve-Souris, which was a big hit on Broadway from February to June 1922. The closest thing to a foundation document for the Algonquin Round Table that one can imagine. An almost mythical single performance that still resonates today. Dorothy Parker sang; Jascha Heifitz provided incidental music from the wings; Robert Benchley first performed his "Treasurer's Report" (which was deliberately left off of the playbill to fool the audience); O'Neill and Milne were spoofed among many others. Benchley's "The Treasurer's Report," was the one element from the performance that later found its own fame. The disjointed parody went over so well that Irving Berlin hired Benchley the following year to perform it as part of Berlin's Music Box Revue for $500 a week.