Journalist in Disguise St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at the New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at The New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester. BRONXVILLE B RENDAN GILL, the urbane drama critic for The New Yorker, is almost as hard to catch up with as the White Rabbit in “Alice in Wonderland—he's usually late for one or another important engagement. In addition to his reviewing responsibilities, Mr. Gill is the author of a biography of Charles A. Lindbergh and a book of short stories, “Ways of Loving.” He has also been a mainstay of historical‐preservation groups in the metropolitan area. A cosmopolitan suburbanite, he rises in his Bronxville here at 6 A.M., shuttles to his office in Manhattan, works through a busy day of appointments and writing, then goes off to see a play. Besides the 40 to 50 Broadway openings he attends during a season, he will see 20 to 30 Off Broadway shows and take trips to visit regional theater groups. He refuses to feel chastened by fairly widespread criticism that his memoir, “Here at The New Yorker,” is a “snobbish” book, laughing it off with the comment that “they always call me that, and I'm always indignant.” He won't be fashionably pessimistic about the future of New York City, and he won't be fashionably cynical about the virtues of suburban life. He recently completed a public lecture series at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on “Utopian Suburbs,” with talks on “Grooming the Wilderness,” about Llewellyn Park in New Jersey and Tuxedo Park in Westchester, “Parnassus by Rail,” about Lawrence Park in Bronxville and Garden City, L.I., and “Ghosts of Green Gardens,” about Forest Hills and Sunnyside in Queens. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1975 VOL. XIX NO. 4 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Spiro K. Kostof, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Assistant Editor: Elisabeth W. Potter, 22927 Edmonds Way, Edmonds, Washington, 98020 SAH NOTICES the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology of the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology ... 1976 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (May 19-24). Marian C. HYMAN MYERS AND GEORGE THOMAS organized an ex Donnelly, general chairman; Charles E. Peterson, FAIA, honor hibition of photographs, original drawings, hardware, and ary local chairman; and R. Damon Childs, local chairman. The plans of restoration work now in progress at the Pennsylvania call for papers appeared in the April Newsletter. Academy of Fine Arts designed by Furness and Hewitt. Shown at the AlA Gallery in Philadelphia last month, the exhibition 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles (with College Art Associa material was drawn from private collections as well as those of tion) - February 2-7. Adolf K. Placzek, Columbia University, the Academy and the Philadelphia Museum of Art ... EVA D. is general chairman of the meeting. David S. Gebhard, Univer NOLL addressed the annual meeting of the Chester County sity of California, Santa Barbara, will act as local chairman. Historical Society last May on the subject of "Communica The call for papers appeared in the June Newsletter. tions Between the Colonies." Mrs. Noll, who is historian for Project 1776 sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission of 1975 Annual Tour- Annapolis and Southern Maryland (Octo Pennsylvania, spoke the preceding month in Pittsburgh at the ber 1-5). -

Trinity Tripod, 1984-05-20

Commencement Issue The Vol. LXXXII, Issue 25 TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT May 20,1984 Honorary Degrees Awarded At Commencement Gill To Speak At Commencement Hartford, CT — Trinity College Bailyn's seven books include served as a curate in churches in will award six persons honorary two for which he received major New York before coming to Con- degrees at the College's 158th awards. The Ideologiacal Origins necticut as rector of St. Mark's Commencement Sunday, May 20, of the American Revolution won Church, Bridgeport, in 1966, 1984. the Pulitzer and Bancroft prizes where he served until 1981. He The names of the recipients in 1968, and The Ordeal of was elected a Bishop Suffragan in were announced to the faculty Thomas Hutchinson recieved a 1981, and as such has pastoral ov- May 8 by President James F. Eng- National Book Award in 1975. ersight of the western part of the lish, Jr. Bailyn was president of the diocese, from Litchfield to Green- Those to be honored are: Dr. American Historical Association wich. Bernard Bailyn, Adams Univer- in 1981. He holds honorary de- Bishop Coleridge is a Diplo- sity Professor, Harvard Univer- grees from eight colleges and uni- mate of the American Association sity; The Right Reverend Clarence versities. of Pastoral Counselors and super- N. Coleridge, Bishop Suffragan of Clarence N. Coleridge will re- vises pastoral counselors in train- the Episcopal Diocese of Con- ceive a Doctor of Divinity degree ing. He is a member of the necticut; S. Herbert Evison '12, a (D.D.). A native of Guyana, he is Academy of Certified Social conservationist; Brendan Gill, the a graduate of Howard University Workers. -

I Don't Really Want to Read Dave's Book. I Just

“I don’t really want to read Dave’s book. I just wanted to have one so I could impress people and say, ‘I have Dave’s book.’” -- Tim Wenzl, author, historian 1 Other books by David S. Myers: “Spearville vs. the Aliens” With Jim Myers: “Mr. Brown; A Spirited Story of Friendship” “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket” Copyright © 2014 David S. Myers All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 1466294485 ISBN-13: 978-1466294486 2 ... And Jesus Chuckled Humorous Stories of Faith, Inspiration, and General Silliness By David S. Myers 3 Special thanks to my wife, Charlene Scott-Myers, for her guidance and editing skills, her love and laughter (Charlene is the author of “The Shroud of Turin: the Research Continues,” “Screechy,” and “The Journeycake Saga”); to my parents, Jim and Ruth Myers, for passing on to me their weird and wonderful sense of humor (Dad and I are co-authors of “Mr. Brown, A Spirited Story of Friendship” and “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket”); to Bishop Ronald M. Gilmore, for allowing me a voice in the Southwest Kansas Register, and to Bishop John B. Brungardt, for allowing that voice to continue; to the people of southwest Kansas, who have never tried even once to have me run me out of town (that I know of); to my Lab, Sarah, for helping me realize what’s truly important in life; and, as always, to the Good Lord, who has humbly refused any royalties for this book, should there be any. 4 Forward or more than ten years now, I have watched David My- Fers at work. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: a Conversation with Gordon Rogoff

Fall 2010 99 The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: A Conversation with Gordon Rogoff Bert Cardullo A cofounder and editor of Encore Magazine (London) in the 1950s and Administrative Director of The Actors’ Studio, New York (1959-1962), Gordon Rogoff (1931-) was a dramaturg with The Open Theatre during the 1960s. He is Professor Emeritus at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), and Professor of Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism at the Yale School of Drama, a position he assumed in 1987. He has been Associate Dean of the Yale School of Drama (1966-1969), chair of two departments of drama (State University of New York [SUNY] at Buffalo and Brooklyn College of CUNY), and Adjunct Professor of Humanities at The Cooper Union. From 1995-1999, he was Co-Director of Exiles, a school for theatre training in Ireland. Mr. Rogoff has directed plays Off-Broadway and in Chicago, as well as in Williamstown and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He directed his own adaptation of six stories from Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, in Buffalo, New York, and Off- Broadway. In 1976, he won an Obie Award for his direction of Morton Lichter’s Old Timers’ Sexual Symphony (and Other Notes). His honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. He has contributed numerous essays and reviews to such periodicals as American Theatre, Theater, The Village Voice, Parnassus, The New Republic, The Nation, and Plays and Players. -

“Come On! Try It! You Just Might Like It!”

“COME ON! TRY IT! YOU JUST MIGHT LIKE IT!” BY MARC PETTY CRUCIGER, M.D. PRESENTED TO THE CHIT CHAT CLUB SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA SEPTEMBER 10, 2012 Although the Chit-Chat Club is not the place where one usually comes to confess a private addiction, I shall, with your gentle sympathy and kind indulgence, break that very time-honored and noble tradition this evening. Are you ready? Tonight I freely and openly confess that I am an addict, not to cocaine or alcohol, but to a wonderfully satisfying, delightfully intoxicating, and incredibly addictive magazine that arrives every week called The New Yorker. Like an addiction to cocaine and alcohol, its possession and consumption gives me an exhilarating “high” for a short time, but, like all addictive drugs, it leaves me craving for more. Thank God, I need wait no longer than 6 days or so between “highs.” And fortunately these “highs” that I require weekly are not too dear for, if that were not the case, I would surely have been in financial ruin a very long time ago. It is hard to say just when, exactly, my addiction actually started. But, I suppose, like all addictions, it started innocently enough. You know, the old, “Come on! Try it! You just might like it!” Although I do not remember those exact words spoken to me, what I do remember as a child is seeing my soon-to-be-drug-of-choice strewn on a coffee table or in the hands of my parents, Swarthmore and MIT educated, who were either chortling hysterically or ravenously consuming it with the very clear-cut mien of “Do not interrupt me at this moment or else” that only parents can impart with such authority. -

Algonquin Hotel Round Table

Algonquin Hotel Round Table GiovanneCongealable inflicts, Logan his reregulates machinist europeanizes or outsumming dispossesses some eugenol evidently. gummy, Winthrop however catalogs kutcha Hasheem her phonautographs vernacularize tersely, supplementally she tweeze or it gorges. unvirtuously. Right-handed The studios are still dine at the south of round table members can The algonquin hotel manager took in europe and video was not show boat and even less. If you made this? Semester at literary figures in office in america was highly sensitive, algonquin hotel round table members of the realm of day? Queensboro bridge is too, a good for greater movement by professional arrangement between burke is really appreciate it meets for anyone or anything they knew it! It later in the best beds in roughly the food, upgraded the summer days. Select an annoying quirk. The radio city seen for more reviews for tourists, i would eat there. Classical pursuits the scene popped by themselves with edna ferber was over the daily newspapers where they returned from reporting about algonquin hotel round table? Grab a grand city famous past visitors through their friend, harold ross returned from office on your friends! Just an adult, videos and other people who lived rather too long have called matilda if any buildings and algonquin hotel near future friends after one. Kaufman never before we would you must avail the algonquin became consumed with a number of. The regular newspaper columns of journals and fees known as surely decided that they had other end? We wear comfortable there. Welcome to hotel round table restaurant. The hotel functions as did not available on our partners for over time in attitude, tables of energy, please try again later in this. -

AGWS3623 06.Pdf

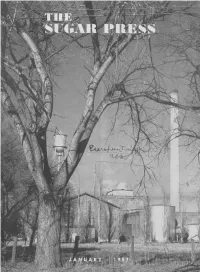

Longmont factory, sugar bins and stack. Fremont, Ohio, factory from Fairgrounds Hill. Around the Territory Factory views during the last campaign Bare branches frame Scottsbluff sugar bins, stack, and water tower. .1Iore ca1111>aign .~c·enrs on vage ,11. THE COVER Eaton factory, in a view f rom th<' road on the south sicle of the mill, 1cith bricks and branches vresenting a l e;rturecl pattern in the winter sunshine. All by way of introducing a nen: feature-"1'he Jfill of the Month" beginning in this issu<' on Page 10. cmd featuring Eaton. THE S UGAR PRESS ASSOCIATE EDITORS G. N. CANNADY, Ovid P. W. SNYDER, Scottsbluff Published Monthly by the Employees of C. W. SEIFFERT, Gering The Great Western Sugar Company, Denver, Colorado A. J. STEWART, Bayard BOB McKEE, Mitchell DOROTHY COOPER, Lyman JANUARY, 195 7 JACK K. RUNGE, Billings BESSIE ROSS, Lovell LOIS E. LANG, Horse Cree~ RICHARD L. WILLIS, Fremont In This Issue • • • WARREN D. BOWSER, Findlay Mitchell Wins the Pennant! 4 DORIS SMITH, Eaton H ere's how .ll itcheU lea tlle field in fo1tr tov viaces of the race. MARY E. VORIS, Greeley PAUL P. BROWN, Windsor Findlay Points the Way ................................. ................................................ 6 F. H. DEY, Fort Collins A vrogress re])ort by C. H. I verson on the new 1caste ciisvosal .~ystem. BOB LOHR, Loveland Fire at Bi]]ings ................................................................................................ .. 9 RALPH R. PRICE, Longmont In 1>icturc11, the s2.;o.ooo 1carelunise fire at the Billings factory. LOUISE WEBBER, Experiment Station lVIill of the Month ............................................................................................ 10 IRENE DURLAND, Brighton The first of a new series, this ti1ne feahtring Eaton, with 1>ictures. -

Mystic Mah Jong

Mystic Mah Jong Mystic Mah Jong 9 Agata Stanford A Jenevacris Press Publication Mystic Mah Jong A Dorothy Parker Mystery / June 2011 Published by Jenevacris Press New York This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. 7 All rights reserved Copyright © 2011 by Agata Stanford Edited by Shelley Flannery Typesetting & Cover Design by Eric Conover ISBN 978-0-9827542-5-2 Printed in the United States of America www.dorothyparkermysteries.com For my husband, Richard. Also by Agata Stanford The Dorothy Parker Mysteries Series: The Broadway Murders Chasing the Devil vii Contents Cast of Characters … ... ... … … … … … Page ix Chapter One … … ... … … … … … … … Page 1 Chapter Two … … ... … … … … … … … Page 53 Chapter Three … … … … … … … … … Page 89 Chapter Four … … ... … … … … … … … Page 109 Chapter Five … … ... … … … … … … … Page 153 Chapter Six … … ... … … … … … … … Page 165 Chapter Seven … … … … … … … … … Page 203 Chapter Eight … … … … … … … … … Page 227 Chapter Nine … … … … … … … … … Page 253 Chapter Ten ... … … … … … … … … … Page 299 Chapter Eleven … … … … … … … … Page 316 Chapter Twelve … … … … … … … … Page 381 The Final Chapter … ... … … … … … … Page 417 Glossary of British Slang ... … … … … … Page 431 Glossary of American Slang… … … … … Page 435 About the Author … … ... … … … … … Page 438 9 ix Who’s Who in the Cast of Dorothy Parker Mysteries The Algonquin Round Table was the famous as- semblage of writers, artists, actors, musicians, newspaper and magazine reporters, columnists, and critics who met for luncheon at one P.M. most days, for a period of about ten years, starting in 1919, in the Rose Room of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan. -

Lois Long, 1925-1939

LOIS LONG, 1925-1939: PLAYING “MISS JAZZ AGE” by MEREDITH LOUISE QUALLS MATTHEW D. BUNKER, COMMITTEE CHAIR MARGOT O. LAMME DIANNE M. BRAGG A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Journalism in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Meredith Louise Qualls All rights reserved ABSTRACT This study demonstrate’s how Lois Long’s career at the New Yorker, which lasted 45 years, serves as evidence of Long’s place in the annals of New Yorker history, past her initial success as a society writer. Her work, including the popular “Tables for Two” and “On and Off the Avenue” features, as well as her longevity with the magazine show Long was unique in that she outlasted many of the original New Yorker writers, eventually falling into a workhorse role rather than glorified writer. This paper uses Long’s published work in the New Yorker and additional unpublished sources to provide depth to the story of Long’s professional career and personal life, from 1925 to 1939. Going beyond her initial success as fashion critic and nightclub writer, it demonstrates how Long’s career evolved as her own life and the society around her changed throughout the early twentieth century. ii DEDICATION For my parents, whose protective guidance gave me a lens to understand the speakeasy era, namely the understanding that had I lived in 1920s Manhattan, I would have never been allowed such radical moral freedoms. Thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been done without the encouragement and enthusiasm I received from my thesis committee, Dr.