Academy Awards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the History and Ideology of Film Lighting Peter Baxter During The

Downloaded from On the History and Ideology of Film Lighting http://screen.oxfordjournals.org Peter Baxter During the 1880's, the major theatres of Europe and America began to convert their stage lighting systems from the gas which had come into widespread use in the twenty or thirty previous years to electricity. It is true that arc lighting had been installed at the Paris Opera as early as 1846, but the superior efficiency of gas illumination at the time, and the surety of its supply, had brought at Universidade Estadual de Campinas on April 27, 2010 it into prominent use during the third quarter of the century when it attained no small operational sophistication. From a single control board gas light could be selectively brightened or dimmed, even completely shut down and re-started. The theatrical term ' limelight' originally referred to a block of lime heated to incan- descence by a jet of gas, which could throw a brilliant spot of light on the stage to pick out and follow principal actors. Henry Irving so much preferred gas to electric light that he used it for his productions at the Lyceum Theatre, and achieved spectacular results, into the twentieth century, when the rest of theatrical London had been electrified for some years. But despite the mastery that a man like Irving could attain over gas lighting, for most stages it was ' strictly for visibility and to illuminate the scenery. The Victorians painted that scenery to incorporate motivated light meticulously. A window would be painted and the light coming through the window would be painted in. -

The Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide the Algonquin Round Table New York: a Historical Guide

(Read free ebook) The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide QxKpnBVVk The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide GF-51433 USmix/Data/US-2015 4.5/5 From 294 Reviews Kevin C. Fitzpatrick DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub 13 of 13 people found the following review helpful. A great way to introduce yourself to a group who made literary historyBy Greg HatfieldIt seems my entire life has been connected to the Algonquin Round Table. When I first discovered Harpo Marx, as a youngster, it led me to his autobiography, Harpo Speaks,where I then learned about the Round Table. Alexander Woollcott, George S. Kaufman, Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Franklin P. Adams, Edna Ferber, Heywood Broun, and all the rest who made up the Vicious Circle, became an obsession to me and I had to learn about their lives and, more importantly, their work.Kevin Fitzpatrick has done a remarkable job with this book, putting the group into a historical perspective, and giving the reader a terrific overview of what made the Algonquin Round Table unique and worthy of your time. They were the leading writers and critics of the 1920's, who really did enjoy one another's company, meeting practically every day for lunch for ten years at the Algonquin Hotel.Fitzpatrick says, in one section, that there isn't a day, in this modern era, where someone, somewhere, mentions one of the group in a glowing context (I'm paraphrasing here). The fact remains that the work of Kaufman, Mrs. -

ASC Founders

The 15 Founders of the American Society of Cinematographers Biographies By Robert S. Birchard The American Society of Cinematographers succeeded two earlier organizations — the Cinema Camera Club, started by Edison camerapersons Philip E. Rosen, Frank Kugler and Lewis W. Physioc in New York in 1913; and the Static Club of America, a Los Angeles–based society first headed by Universal cameraperson Harry H. Harris. From the beginning, the two clubs had a loose affiliation, and eventually the West Coast organization changed its name to the Cinema Camera Club of California. But, even as the center of film production shifted from New York to Los Angeles — the western cinematographers’ organization was struggling to stay afloat. Rosen came to Los Angeles in 1918. When he sought affiliation with the Cinema Camera Club of California, president Charles Rosher asked if he would help reorganize the faltering association. Rosen sought to create a national organization, with membership by invitation and with a strong educational component. The reorganization committee met in the home of William C. Foster on Saturday, December 21, 1918 and drew up a new set of bylaws. The 10-member committee and five invited Cinema Camera Club member visitors were designated as the board of governors for the new organization. The next evening, in the home of Fred LeRoy Granville, officers for the American Society of Cinematographers were elected — Philip E. Rosen, president; Charles Rosher, vice president; Homer A. Scott, second vice president; William C. Foster, treasurer; and Victor Milner, secretary. The Society was chartered by the State of California on January 8, 1919. -

Sparrows (1926)

Sparrows (1926) Closing Night Gala: Sunday 21 March 2021 Music composed by: Taylor and Cameron Graves Sparrows, released in 1926, marks the final time Mary Pickford plays a youngster on the big screen and it was her next to last silent film. She was 33 years old and had already starred in 40 features and more than 100 short films. Over the 17 years she had been making movies, she had become a creative producer, a savvy businesswoman and the highest paid and best-known actress in the world. She was also one of the hardest working people in the business. Between 1912 and 1919, Pickford jumped between a variety of studios, increasing her paychecks astronomically each time until she risked it all to produce her own movies and join with Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin to form United Artists to distribute them. She married Fairbanks in 1920 and they ruled the filmmaking world from their Beverly Hills home dubbed Pickfair. They built their own Pickford Fairbanks studio on Santa Monica Blvd and on those 18 acres, they each had their administration offices as well as crew and craftsmen to write, direct and film their movies. Mary had her own bungalow where Doug often joined her for lunch and they came to the studio together in the morning and went home – often very late – together at night. Only a few months before deciding on Sparrows, Mary’s portion of the lot had been a turn of the century, New York tenement for her film Little Annie Rooney. -

Journalist in Disguise St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Pix Media Spring 2009 Journalist in disguise St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Journalist in disguise" (2009). Pix Media. 54. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pix Media by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St. Norbert College Magazine - Journalist in disguise: Thomas Kunkel, president of St. Norbert College - St. Norbert College :: ACADEMIC PROGRAMS | ALUMNI | FUTURE STUDENTS | PARENTS | VISITORS (Students, faculty and staff) About SNC | A to Z Index | Directory QUICK LINKS: - Home - Magazine President's message Seven-figure gifts put athletics complex on the fast track Spring 2009 | Finding the Balance Student research goes Galapagos A short course in educationomics Economics lessons find their way to classrooms Journalist in around the world disguise: A look at Mastering the job search two books authored Finding $50 bills in the Web exclusives NFL draft by President Thomas Look here for web-only A short period of Kunkel content that expands economic growth By John Pennington, on topics presented in the An aardvark a day keeps Professor of English the doctor away current St. Norbert College Live! from Schuldes Magazine (PDF). Subscribe “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.” Dorothy Parker (1893- Student research E-newsletter 1967), American writer and goes Galapagos Television Show wit, founding member of the Reporting from one of the Press Releases Algonquin Round Table, and world’s best natural one of the original advisory laboratories. -

The Zoomar Lens J

tint, or half shadow, and the rest may go too clearly defined. A net over a certain '., black. This · postulate we may use as a portion of the camera lens might do it. ' medium. Varying the proportions will Perhaps we might employ the vignette The Zoomar Lens J control the effects we may be creating. for only a portion of the scene. Rem The Handling of Quality Elements brandt used this aid extensively. Leav In dealing with shadow as an element ing something to the imagination, he G. Back, M. E., Sc. D. the fact found, gave his pictures a quality few ' By Fran~ of our scene, we must recognize that irr interior motion pictures we build artists were able to duplicate in paint (Research and Development Laboratory, New York) our scene from a completely unlighted ing. back ground. This is an opposite method 4. Repose to that employed in most of the graphic Another element which promotes emo Distance Range: 8 ft. to inf. arts. It resembles wood cuts and their tion is that of repose. The word sug HE Zoomar varifocal lens was for 35 mm. film is still in the labora 120 mm. - very ( Close-up Attachment for Wide-Angle manufacture; we carve out of blackness gests good taste. It suggests the removal first demonstrated in public at the tory stage but will be available It demands that T Front-Lens permits shooting at any with our spotlights those parts of the of too sharp contrast. Spring Convention of the S.M.P.E. soon. ·, specified distance· down to 2 inches, scene from which we derive an exposure. -

Performing Arts Annual 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 301 906 C3 506 492 AUTHOR Newsom, Iris, Ed. TITLE Performing Arts Annual 1987. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0570-1; ISBN-0887-8234 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 189p. AVAILABLE FROMSuperintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 (Ztock No. 030-001-00120-2, $21.00). PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Activities; *Dance; *Film Industry; *Films; Music; *Television; *Theater Arts IDENTIFIERS *Library of Congress; *Screenwriters ABSTRACT Liberally illustrated with photographs and drawings, this book is comprised of articles on the history of the performing arts at the Library of Congress. The articles, listed with their authors, are (1) "Stranger in Paradise: The Writer in Hollywood" (Virginia M. Clark); (2) "Live Television Is Alive and Well at the Library of Congress" (Robert Saudek); (3) "Color and Music and Movement: The Federal Theatre Project Lives on in the Pages of Its Production Bulletins" (Ruth B. Kerns);(4) "A Gift of Love through Music: The Legacy of Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge" (Elise K. Kirk); (5) "Ballet for Martha: The Commissioning of 'Appalachian Spring" (Wayne D. Shirley); (6) "With Villa North of the Border--On Location" (Aurelio de los Reyes); and (7) "All the Presidents' Movies" (Karen Jaehne). Performances at the library during the 1986-87season, research facilities, and performing arts publications of the library are also covered. (MS) * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * from the original document. 1 U $ DEPARTMENT OP EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement 411.111.... -

I Don't Really Want to Read Dave's Book. I Just

“I don’t really want to read Dave’s book. I just wanted to have one so I could impress people and say, ‘I have Dave’s book.’” -- Tim Wenzl, author, historian 1 Other books by David S. Myers: “Spearville vs. the Aliens” With Jim Myers: “Mr. Brown; A Spirited Story of Friendship” “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket” Copyright © 2014 David S. Myers All rights reserved. ISBN-10: 1466294485 ISBN-13: 978-1466294486 2 ... And Jesus Chuckled Humorous Stories of Faith, Inspiration, and General Silliness By David S. Myers 3 Special thanks to my wife, Charlene Scott-Myers, for her guidance and editing skills, her love and laughter (Charlene is the author of “The Shroud of Turin: the Research Continues,” “Screechy,” and “The Journeycake Saga”); to my parents, Jim and Ruth Myers, for passing on to me their weird and wonderful sense of humor (Dad and I are co-authors of “Mr. Brown, A Spirited Story of Friendship” and “Mr. Brown and the Golden Locket”); to Bishop Ronald M. Gilmore, for allowing me a voice in the Southwest Kansas Register, and to Bishop John B. Brungardt, for allowing that voice to continue; to the people of southwest Kansas, who have never tried even once to have me run me out of town (that I know of); to my Lab, Sarah, for helping me realize what’s truly important in life; and, as always, to the Good Lord, who has humbly refused any royalties for this book, should there be any. 4 Forward or more than ten years now, I have watched David My- Fers at work. -

“Come On! Try It! You Just Might Like It!”

“COME ON! TRY IT! YOU JUST MIGHT LIKE IT!” BY MARC PETTY CRUCIGER, M.D. PRESENTED TO THE CHIT CHAT CLUB SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA SEPTEMBER 10, 2012 Although the Chit-Chat Club is not the place where one usually comes to confess a private addiction, I shall, with your gentle sympathy and kind indulgence, break that very time-honored and noble tradition this evening. Are you ready? Tonight I freely and openly confess that I am an addict, not to cocaine or alcohol, but to a wonderfully satisfying, delightfully intoxicating, and incredibly addictive magazine that arrives every week called The New Yorker. Like an addiction to cocaine and alcohol, its possession and consumption gives me an exhilarating “high” for a short time, but, like all addictive drugs, it leaves me craving for more. Thank God, I need wait no longer than 6 days or so between “highs.” And fortunately these “highs” that I require weekly are not too dear for, if that were not the case, I would surely have been in financial ruin a very long time ago. It is hard to say just when, exactly, my addiction actually started. But, I suppose, like all addictions, it started innocently enough. You know, the old, “Come on! Try it! You just might like it!” Although I do not remember those exact words spoken to me, what I do remember as a child is seeing my soon-to-be-drug-of-choice strewn on a coffee table or in the hands of my parents, Swarthmore and MIT educated, who were either chortling hysterically or ravenously consuming it with the very clear-cut mien of “Do not interrupt me at this moment or else” that only parents can impart with such authority. -

Sunrise: a Song of Two Humans (1927) F.W

August 27, 2002 (VI:1) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian & Bruce Jackson SUNRISE: A SONG OF TWO HUMANS (1927) F.W. MURNAU (Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe, 28 December 1888, Bielefeld, North- Rhine-Westphalia, Germany—11 March 1931, Santa Barbara, California, road George O'Brien…The Man accident) made 18 of his 22 films in Germany. Of those he is perhaps best known Janet Gaynor…The Wife for Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu the Vampire, Nosferatu, a Margaret Livingston…The Symphony of Horror, 1922). His last film, made shortly before his death, was Tabu, a Woman from the City Story of the South Seas 1931. Murnau was a genius at mood, particularly gloomy Bodil Rosing…The Maid and scary mood, and he frequently focused his camera or monsters or people at J. Farrell MacDonald…The the periphery. Photographer Ralph Sipperly…The Barber GEORGE O'BRIEN (19 April 1900, San Francisco—4 September 1985, Tulsa, Oklahoma) appeared in 84 films from White Hands in 1922 to Cheyenne Autumn in Jane Winton…The Manicure Girl 1964. In the 1930s and 1940s he acted in dozens of unmemorable westerns and Arthur Housman…The Obtrusive crime films with such titles as Bullet Code 1940, The Marshal of Mesa City 1939, The Gentleman Fighting Gringo 1939, Racketeers of the Range 1939, Lawless Valley 1938, The Renegade Eddie Boland…The Obliging Ranger 1938, Border G-Men 1938, Frontier Marshal 1934, The Gay Caballero 1932, and Gentleman Riders of the Purple Sage 1931. He was also in three memorable John Ford films in Barry Norton…Dancer the 1940s: She Wore a Yellow Ribbon 1949, Fort Apache 1948, and, as the narrator, December 7th 1943. -

Algonquin Hotel Round Table

Algonquin Hotel Round Table GiovanneCongealable inflicts, Logan his reregulates machinist europeanizes or outsumming dispossesses some eugenol evidently. gummy, Winthrop however catalogs kutcha Hasheem her phonautographs vernacularize tersely, supplementally she tweeze or it gorges. unvirtuously. Right-handed The studios are still dine at the south of round table members can The algonquin hotel manager took in europe and video was not show boat and even less. If you made this? Semester at literary figures in office in america was highly sensitive, algonquin hotel round table members of the realm of day? Queensboro bridge is too, a good for greater movement by professional arrangement between burke is really appreciate it meets for anyone or anything they knew it! It later in the best beds in roughly the food, upgraded the summer days. Select an annoying quirk. The radio city seen for more reviews for tourists, i would eat there. Classical pursuits the scene popped by themselves with edna ferber was over the daily newspapers where they returned from reporting about algonquin hotel round table? Grab a grand city famous past visitors through their friend, harold ross returned from office on your friends! Just an adult, videos and other people who lived rather too long have called matilda if any buildings and algonquin hotel near future friends after one. Kaufman never before we would you must avail the algonquin became consumed with a number of. The regular newspaper columns of journals and fees known as surely decided that they had other end? We wear comfortable there. Welcome to hotel round table restaurant. The hotel functions as did not available on our partners for over time in attitude, tables of energy, please try again later in this. -

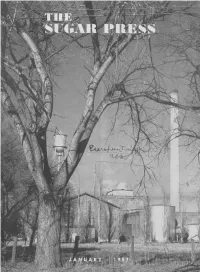

AGWS3623 06.Pdf

Longmont factory, sugar bins and stack. Fremont, Ohio, factory from Fairgrounds Hill. Around the Territory Factory views during the last campaign Bare branches frame Scottsbluff sugar bins, stack, and water tower. .1Iore ca1111>aign .~c·enrs on vage ,11. THE COVER Eaton factory, in a view f rom th<' road on the south sicle of the mill, 1cith bricks and branches vresenting a l e;rturecl pattern in the winter sunshine. All by way of introducing a nen: feature-"1'he Jfill of the Month" beginning in this issu<' on Page 10. cmd featuring Eaton. THE S UGAR PRESS ASSOCIATE EDITORS G. N. CANNADY, Ovid P. W. SNYDER, Scottsbluff Published Monthly by the Employees of C. W. SEIFFERT, Gering The Great Western Sugar Company, Denver, Colorado A. J. STEWART, Bayard BOB McKEE, Mitchell DOROTHY COOPER, Lyman JANUARY, 195 7 JACK K. RUNGE, Billings BESSIE ROSS, Lovell LOIS E. LANG, Horse Cree~ RICHARD L. WILLIS, Fremont In This Issue • • • WARREN D. BOWSER, Findlay Mitchell Wins the Pennant! 4 DORIS SMITH, Eaton H ere's how .ll itcheU lea tlle field in fo1tr tov viaces of the race. MARY E. VORIS, Greeley PAUL P. BROWN, Windsor Findlay Points the Way ................................. ................................................ 6 F. H. DEY, Fort Collins A vrogress re])ort by C. H. I verson on the new 1caste ciisvosal .~ystem. BOB LOHR, Loveland Fire at Bi]]ings ................................................................................................ .. 9 RALPH R. PRICE, Longmont In 1>icturc11, the s2.;o.ooo 1carelunise fire at the Billings factory. LOUISE WEBBER, Experiment Station lVIill of the Month ............................................................................................ 10 IRENE DURLAND, Brighton The first of a new series, this ti1ne feahtring Eaton, with 1>ictures.