Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at the New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1975 VOL. XIX NO. 4 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Spiro K. Kostof, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Assistant Editor: Elisabeth W. Potter, 22927 Edmonds Way, Edmonds, Washington, 98020 SAH NOTICES the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology of the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology ... 1976 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (May 19-24). Marian C. HYMAN MYERS AND GEORGE THOMAS organized an ex Donnelly, general chairman; Charles E. Peterson, FAIA, honor hibition of photographs, original drawings, hardware, and ary local chairman; and R. Damon Childs, local chairman. The plans of restoration work now in progress at the Pennsylvania call for papers appeared in the April Newsletter. Academy of Fine Arts designed by Furness and Hewitt. Shown at the AlA Gallery in Philadelphia last month, the exhibition 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles (with College Art Associa material was drawn from private collections as well as those of tion) - February 2-7. Adolf K. Placzek, Columbia University, the Academy and the Philadelphia Museum of Art ... EVA D. is general chairman of the meeting. David S. Gebhard, Univer NOLL addressed the annual meeting of the Chester County sity of California, Santa Barbara, will act as local chairman. Historical Society last May on the subject of "Communica The call for papers appeared in the June Newsletter. tions Between the Colonies." Mrs. Noll, who is historian for Project 1776 sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission of 1975 Annual Tour- Annapolis and Southern Maryland (Octo Pennsylvania, spoke the preceding month in Pittsburgh at the ber 1-5). -

Journalist in Disguise St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Pix Media Spring 2009 Journalist in disguise St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Journalist in disguise" (2009). Pix Media. 54. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pix Media by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St. Norbert College Magazine - Journalist in disguise: Thomas Kunkel, president of St. Norbert College - St. Norbert College :: ACADEMIC PROGRAMS | ALUMNI | FUTURE STUDENTS | PARENTS | VISITORS (Students, faculty and staff) About SNC | A to Z Index | Directory QUICK LINKS: - Home - Magazine President's message Seven-figure gifts put athletics complex on the fast track Spring 2009 | Finding the Balance Student research goes Galapagos A short course in educationomics Economics lessons find their way to classrooms Journalist in around the world disguise: A look at Mastering the job search two books authored Finding $50 bills in the Web exclusives NFL draft by President Thomas Look here for web-only A short period of Kunkel content that expands economic growth By John Pennington, on topics presented in the An aardvark a day keeps Professor of English the doctor away current St. Norbert College Live! from Schuldes Magazine (PDF). Subscribe “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.” Dorothy Parker (1893- Student research E-newsletter 1967), American writer and goes Galapagos Television Show wit, founding member of the Reporting from one of the Press Releases Algonquin Round Table, and world’s best natural one of the original advisory laboratories. -

Trinity Tripod, 1984-05-20

Commencement Issue The Vol. LXXXII, Issue 25 TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT May 20,1984 Honorary Degrees Awarded At Commencement Gill To Speak At Commencement Hartford, CT — Trinity College Bailyn's seven books include served as a curate in churches in will award six persons honorary two for which he received major New York before coming to Con- degrees at the College's 158th awards. The Ideologiacal Origins necticut as rector of St. Mark's Commencement Sunday, May 20, of the American Revolution won Church, Bridgeport, in 1966, 1984. the Pulitzer and Bancroft prizes where he served until 1981. He The names of the recipients in 1968, and The Ordeal of was elected a Bishop Suffragan in were announced to the faculty Thomas Hutchinson recieved a 1981, and as such has pastoral ov- May 8 by President James F. Eng- National Book Award in 1975. ersight of the western part of the lish, Jr. Bailyn was president of the diocese, from Litchfield to Green- Those to be honored are: Dr. American Historical Association wich. Bernard Bailyn, Adams Univer- in 1981. He holds honorary de- Bishop Coleridge is a Diplo- sity Professor, Harvard Univer- grees from eight colleges and uni- mate of the American Association sity; The Right Reverend Clarence versities. of Pastoral Counselors and super- N. Coleridge, Bishop Suffragan of Clarence N. Coleridge will re- vises pastoral counselors in train- the Episcopal Diocese of Con- ceive a Doctor of Divinity degree ing. He is a member of the necticut; S. Herbert Evison '12, a (D.D.). A native of Guyana, he is Academy of Certified Social conservationist; Brendan Gill, the a graduate of Howard University Workers. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: a Conversation with Gordon Rogoff

Fall 2010 99 The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: A Conversation with Gordon Rogoff Bert Cardullo A cofounder and editor of Encore Magazine (London) in the 1950s and Administrative Director of The Actors’ Studio, New York (1959-1962), Gordon Rogoff (1931-) was a dramaturg with The Open Theatre during the 1960s. He is Professor Emeritus at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), and Professor of Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism at the Yale School of Drama, a position he assumed in 1987. He has been Associate Dean of the Yale School of Drama (1966-1969), chair of two departments of drama (State University of New York [SUNY] at Buffalo and Brooklyn College of CUNY), and Adjunct Professor of Humanities at The Cooper Union. From 1995-1999, he was Co-Director of Exiles, a school for theatre training in Ireland. Mr. Rogoff has directed plays Off-Broadway and in Chicago, as well as in Williamstown and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He directed his own adaptation of six stories from Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, in Buffalo, New York, and Off- Broadway. In 1976, he won an Obie Award for his direction of Morton Lichter’s Old Timers’ Sexual Symphony (and Other Notes). His honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. He has contributed numerous essays and reviews to such periodicals as American Theatre, Theater, The Village Voice, Parnassus, The New Republic, The Nation, and Plays and Players. -

Lois Long, 1925-1939

LOIS LONG, 1925-1939: PLAYING “MISS JAZZ AGE” by MEREDITH LOUISE QUALLS MATTHEW D. BUNKER, COMMITTEE CHAIR MARGOT O. LAMME DIANNE M. BRAGG A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Journalism in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Meredith Louise Qualls All rights reserved ABSTRACT This study demonstrate’s how Lois Long’s career at the New Yorker, which lasted 45 years, serves as evidence of Long’s place in the annals of New Yorker history, past her initial success as a society writer. Her work, including the popular “Tables for Two” and “On and Off the Avenue” features, as well as her longevity with the magazine show Long was unique in that she outlasted many of the original New Yorker writers, eventually falling into a workhorse role rather than glorified writer. This paper uses Long’s published work in the New Yorker and additional unpublished sources to provide depth to the story of Long’s professional career and personal life, from 1925 to 1939. Going beyond her initial success as fashion critic and nightclub writer, it demonstrates how Long’s career evolved as her own life and the society around her changed throughout the early twentieth century. ii DEDICATION For my parents, whose protective guidance gave me a lens to understand the speakeasy era, namely the understanding that had I lived in 1920s Manhattan, I would have never been allowed such radical moral freedoms. Thank you. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been done without the encouragement and enthusiasm I received from my thesis committee, Dr. -

The Publication of “Hiroshima” in the New Yorker

Steve Rothman HSCI E-196 Science and Society in the 20th Century Professor Everett Mendelsohn January 8, 1997 The Publication of “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker Overview A year after World War II ended, a leading American weekly magazine published a striking description of what life was like for those who survived a nuclear attack. The article, simply titled “Hiroshima,” was published by The New Yorker in its August 31, 1946 issue. The thirty-one thousand word article displaced virtually all other editorial matter in the issue. “Hiroshima” traced the experiences of six residents who survived the blast of August 6, 1945 at 8:15 am. There was a personnel clerk, Miss Toshiko Sasaki; a physician, Dr. Masakazu Fujii; a tailor’s widow with three small children, Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura; a German missionary priest, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge; a young surgeon, Dr. Terufumi Sasaki; and a Methodist pastor, the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto. The article told the story of their experiences, starting from when the six woke up that morning, to what they were doing the moment of the blast and the next few hours, continuing through the next several days and then ending with the situations of the six survivors several months later. The article, written by John Hersey, created a blast of its own in the publishing world. The New Yorker sold out immediately, and requests for reprints poured in from all over the world. Following publication, “Hiroshima” was read on the radio in the United States and abroad. Other magazines S. Rothman page 2 reviewed the article and referred their readers to it. -

John Cheever's Relationship with the American Magazine

JOHN CHEEVER’S RELATIONSHIP WITH THE AMERICAN MAGAZINE MARKETPLACE, 1930 to 1964 JAMES RICHARD MONKMAN Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 Abstract John Cheever published over two hundred short stories in an array of small-, mid-, and large-circulation magazines between 1930 and 1981. One hundred and twenty of these stories appeared in The New Yorker. During Cheever’s career and since his death in 1982, many critics have typically analysed his short stories in isolation from the conditions of their production, lest Cheever’s subversive modernist tendencies be confused with the conservative middlebrow ethos of The New Yorker, or the populist aspect of other large- circulation magazines. Critics, including Cheever’s daughter and his most recent biographer Blake Bailey, also claim that Cheever was a financial and, ultimately, artistic victim of the magazine marketplace. Drawing on largely unpublished editorial and administrative correspondence in the New Yorker Records and editorially annotated short story typescripts in the John Cheever Literary Manuscripts collection, and using a historicised close-reading practice, this thesis examines the influence of the magazine marketplace on the short fiction that Cheever produced between 1930 and 1964. It challenges the critical consensus by arguing that Cheever did not dissociate his authorship from commerciality at any point during his career, and consistently exploited the magazine marketplace to his financial and creative advantage, whether this meant temporarily producing stories for little magazines in the early 1930s and romance stories for mainstream titles in the 1940s, or selling his New Yorker rejections to its rivals, which he did throughout his career. -

Joe Mitchell, Jack Alexander, Richard O

Joseph Mitchell and The New Yorker Nonfiction Writers by Norman Sims From Literary Journalism in the Twentieth Century, edited by Norman Sims (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press, 2008). (Originally written before The New Yorker moved to its new offices. Also written prior to the publication of Joseph Mitchell’s Up in the Old Hotel, which used some of the text from my interview as Mitchell’s jacket copy.) At The New Yorker, when you get off the elevator you step into an off-white, narrow little prison of a waiting room. The receptionist phones the inner sanctum of the editorial offices, and your host meets you at the door. My host was Joseph Mitchell, who has been with The New Yorker since 1938. Although he was eighty-one-years-old and rumored to be a ghostly presence in the corridors of the magazine, he carried the grace of a much younger man. Mitchell’s last magazine article appeared in 1964. He has regularly gone to his office since then, feeding the speculation that this very private man has been writing some magnificent addition to the books he published between 1938 and 1965.1 Curiosity has been fed by Mitchell’s own last work, Joe Gould’s Secret, and by the appearance of a character similar to him in Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City. Not surprisingly, given his longevity at the institution, his office is the first one down the hallway. The furnishings—metal desk, cabinets, flooring that dates from the age of linoleum—are standard at The New Yorker. -

The Trinity Reporter, Summer 1984

JRiNIRT'f COLLEGE LIBRAIU' ECEIVED · ocr 26 1984 ARTFORD, CONN. National Alumni Association EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS President Victor F. Keen '63, New York, NY Senior Vice President William H. Schweitzer '66, Washington, D.C. Vice Presidents Alumni Fund Peter A. Hoffman '61, New York, NY Campus Activities Jeffrey J. Fox '67, Avon, CT Admissions Susan Martin Haberlandt '71, West Hartford, CT Area Associations Merrill A. Y avinsky '65, Potomac, MD Public Relations Wenda Harris Millard '76, New York, NY Career Counseling Robert E. Brickley '67, West Hartford, CT Secretary-Treasurer Alfred Steel, Jr. '64, West Hartford, CT MEMBERS B. Graeme Frazier III '57, Philadelphia, PA Megan O'Neill '73, West Hartford, CT Charles E. Gooley '75, Bloomfield, CT James A. Finkelstein '74, La Jolla, CA Richard P. Morris '68, Dresher, PA Robert N. Hunter '52, Glastonbury, CT, Ex-Officio Elizabeth Kelly Droney '79, West Hartford, CT Athletic Advisory Committee Term Expires Edward S. Ludorf '51, Simsbury, CT 1984 Donald J. Viering '42, Simsbury, CT 1984 Susan Martin Haberlandt '71, West Hartford, CT 1985 Alumni Trustees Term Expires Emily G. Holcombe '74, Hartford, CT 1985 Marshall E. Blume '63, Villanova, PA 1986 Stanley J. Marcuss '63, Washington, D.C. 1987 Donald L. McLagan '64, Sudbury, MA 1988 David R. Smith '52, Greenwich, CT 1989 Carolyn A. Pelzel '74, Hampstead, NH 1990 Nominating Committee Term Expires John C. Gunning '49, West Hartford, CT 1984 Wenda Harris Millard '76, New York, NY 1984 Norman C. Kayser '57, West Hartford, CT 1984 Peter Lowenstein '58, Riverside, CT 1984 William Vibert '52, Granby, CT 1984 BOARD OF FELLOWS Dana M. -

Drumming up Support for Tin Pan Alley Designation

SPRING 2018 [email protected] | 212-886-3742 WWW.VICSOCNY.ORG the new york metropolitan chapter of the victorian society in america Drumming Up Support VSNY INITIATES LAND- MARK EVALUATION For Tin Pan Alley Designation A request for evaluation filed On the snippet of West 28th Street that links Broadway on behalf of the Victorian and 6th Avenue in Manhattan, the storefronts overflow Society New York by board member Alta Indelman asked with wigs, beaded slippers, paper lanterns, phone cases the Landmarks Preserva- and knit ponchos. What you will not find in its windows tion Commission to consider anymore, and what you would have been offered at designating the school at 131 every turn circa 1900, is brand-new sheet music. Sixth Avenue in Manhattan as From the 1890s to the 1910s, composers, performers an individual landmark. and music publishers and impresarios rented offices on Now home to Chelsea the block in four- and five-story structures built as early Career and Technical Educa- as the 1830s. Hits like “Give My Regards to Broadway” tion High School and the New and “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” were first played York City iSchool, the building was completed in 1905 to the on the tenants’ pianos, with cardboard muffling the design of C.B.J. Snyder, the soundboard strings (to keep competitors from hearing legendary superintendent the melodies in progress). The pervasive tinny sound of buildings for the Board of inspired the block’s nickname, Tin Pan Alley. Buildings from the glory days of Tin Pan Alley remain on West 28th Street in Manhattan.Photo courtesy of Historic Education from 1891-1922. -

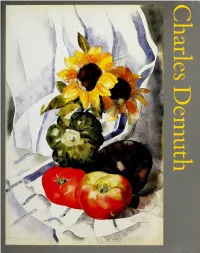

Charles Demuth / Barbara Haskell

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/charlesdemuthbar2402hask Charles Demuth Barbara Haskell Charles Dei Whitney Museum of American Art, New York in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, New York : Exhibition Itinerary: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York October 15, 1987-January 17, 1988 Los Angeles County Museum of Art February 25-April 24, [988 Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio May 8-July 10, 1988 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art August 7-Octobcr 2, 1988 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Haskell, Barbara. Charles Demuth, Exhibition catalog. Bibliography: p. 1. Demuth, Charles, 1 883-1935 — Exhibitions. 2. Painting, American —Exhibitions. 3. Painting, Modern — 20th century— United States- Exhibitions. 4. Painters — Pennsylvania — biography. I. Demuth, Charles, 1883-1935. II. Whitney Museum of American Art. III. Title. ND237.D36A4 1987 75913 87-18872 isbn 0-87427-056-1 (paper) ISBN O-8IO9-II35-3 (cloth) Cover From the Kitchen Garden, 1925 (Pi. 88) Frontispiece: Man Ray 3 Charles Demuth Hands, and Torso, c. 1921 ; Silver print, 9% x 6 A in. (23 I x 27.1 cm); Private collection This publication was organized at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Doris Palca, Head, Publications and Sales; Sheila Schwartz, Editor; Deborah Lyons, Associate Editor; and Vicki Drake, Secretary/ Assistant. Charles Demuth was designed by Katy Homans, Homans/Salsgiver; typeset in Monotype Bembo by Michael and Winifred Bixler; and printed in Japan by Nissha Printing Co., Ltd. Copyright © 1987 Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue, New York 10021 1 Contents Director's Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 I.