The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: a Conversation with Gordon Rogoff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at the New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at The New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester. BRONXVILLE B RENDAN GILL, the urbane drama critic for The New Yorker, is almost as hard to catch up with as the White Rabbit in “Alice in Wonderland—he's usually late for one or another important engagement. In addition to his reviewing responsibilities, Mr. Gill is the author of a biography of Charles A. Lindbergh and a book of short stories, “Ways of Loving.” He has also been a mainstay of historical‐preservation groups in the metropolitan area. A cosmopolitan suburbanite, he rises in his Bronxville here at 6 A.M., shuttles to his office in Manhattan, works through a busy day of appointments and writing, then goes off to see a play. Besides the 40 to 50 Broadway openings he attends during a season, he will see 20 to 30 Off Broadway shows and take trips to visit regional theater groups. He refuses to feel chastened by fairly widespread criticism that his memoir, “Here at The New Yorker,” is a “snobbish” book, laughing it off with the comment that “they always call me that, and I'm always indignant.” He won't be fashionably pessimistic about the future of New York City, and he won't be fashionably cynical about the virtues of suburban life. He recently completed a public lecture series at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on “Utopian Suburbs,” with talks on “Grooming the Wilderness,” about Llewellyn Park in New Jersey and Tuxedo Park in Westchester, “Parnassus by Rail,” about Lawrence Park in Bronxville and Garden City, L.I., and “Ghosts of Green Gardens,” about Forest Hills and Sunnyside in Queens. -

Local Pictures Needed for Coming Celebration

VOL. Ill, NO. 49 • $1.00 A YEAR "~potllgllt NOVEMBER 13, 1958 • TEN CENTS A WEEKLY NEWSMAGAZINE A· D A I L Y H A B I T Will You Be There? "YEARS AGO" SCHEDULED LOCAL PICTURES NEEDED FOR BY LOCAL PLAYERS Mrs. Betty Sherwin, Chairman1 Motor Service, Albany County COMING CELEBRATION "Years Ago, 11 a comedy by Chapter, American Red Cross, Ruth Gordon, will open at the announced today the second an Hudson and Champlain sail a pictorial history exhibit, includ Bethlehem Central Junior High nual training •course for those in gain • • • and ideas about their ing many periods of town his School on Wednesday, Novem terested in joining as volunteer historical time and period are tory, is being sought. ber 19, at 8:30 p.m. The play, drivers. The course, under the causing many a group and com It is not necessary to have a which is presented in arena style leadership of Mrs. E.L. Larcher, mittee to unfurl their sails and pictme of Hemy Hudson riding by the Slingerlands Community Training Chairman for the Ser establish their communities par at anchor at the mouth of the Players, will run for four suc 1 vice, is scheduled for November ticipation in New York State s Normanskill; or of Albery Bradt, cessive nights. All seats are re 12, 19, and 25, and December year of Historical obserVances, who leased mill privileges on the served. Tickets may be ordered 3 and 10, fl'om 7:30 to 9:30 which begins January 1, 1959. No"rmanskill in 1630, and is con by telephoning 9-4158 or may be p.m. -

Good Chemistry James J

Columbia College Fall 2012 TODAY Good Chemistry James J. Valentini Transitions from Longtime Professor to Dean of the College your Contents columbia connection. COVER STORY FEATURES The perfect midtown location: 40 The Home • Network with Columbia alumni Front • Attend exciting events and programs Ai-jen Poo ’96 gives domes- • Dine with a client tic workers a voice. • Conduct business meetings BY NATHALIE ALONSO ’08 • Take advantage of overnight rooms and so much more. 28 Stand and Deliver Joel Klein ’67’s extraordi- nary career as an attorney, educator and reformer. BY CHRIS BURRELL 18 Good Chemistry James J. Valentini transitions from longtime professor of chemistry to Dean of the College. Meet him in this Q&A with CCT Editor Alex Sachare ’71. 34 The Open Mind of Richard Heffner ’46 APPLY FOR The venerable PBS host MEMBERSHIP TODAY! provides a forum for guests 15 WEST 43 STREET to examine, question and NEW YORK, NY 10036 disagree. TEL: 212.719.0380 BY THOMAS VIncIGUERRA ’85, in residence at The Princeton Club ’86J, ’90 GSAS of New York www.columbiaclub.org COVER: LESLIE JEAN-BART ’76, ’77J; BACK COVER: COLIN SULLIVAN ’11 WITHIN THE FAMILY DEPARTMENTS ALUMNI NEWS Déjà Vu All Over Again or 49 Message from the CCAA President The Start of Something New? Kyra Tirana Barry ’87 on the successful inaugural summer of alumni- ete Mangurian is the 10th head football coach since there, the methods to achieve that goal. The goal will happen if sponsored internships. I came to Columbia as a freshman in 1967. (Yes, we you do the other things along the way.” were “freshmen” then, not “first-years,” and we even Still, there’s no substitute for the goal, what Mangurian calls 50 Bookshelf wore beanies during Orientation — but that’s a story the “W word.” for another time.) Since then, Columbia has compiled “The bottom line is winning,” he said. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1975 VOL. XIX NO. 4 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Spiro K. Kostof, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Assistant Editor: Elisabeth W. Potter, 22927 Edmonds Way, Edmonds, Washington, 98020 SAH NOTICES the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology of the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology ... 1976 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (May 19-24). Marian C. HYMAN MYERS AND GEORGE THOMAS organized an ex Donnelly, general chairman; Charles E. Peterson, FAIA, honor hibition of photographs, original drawings, hardware, and ary local chairman; and R. Damon Childs, local chairman. The plans of restoration work now in progress at the Pennsylvania call for papers appeared in the April Newsletter. Academy of Fine Arts designed by Furness and Hewitt. Shown at the AlA Gallery in Philadelphia last month, the exhibition 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles (with College Art Associa material was drawn from private collections as well as those of tion) - February 2-7. Adolf K. Placzek, Columbia University, the Academy and the Philadelphia Museum of Art ... EVA D. is general chairman of the meeting. David S. Gebhard, Univer NOLL addressed the annual meeting of the Chester County sity of California, Santa Barbara, will act as local chairman. Historical Society last May on the subject of "Communica The call for papers appeared in the June Newsletter. tions Between the Colonies." Mrs. Noll, who is historian for Project 1776 sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission of 1975 Annual Tour- Annapolis and Southern Maryland (Octo Pennsylvania, spoke the preceding month in Pittsburgh at the ber 1-5). -

Ii. Theory and Practice of Editing New Yorker Articles

II. THEORY AND PRACTICE OF EDITING NEW YORKER ARTICLES This was written by Wolcott Gibbs around 1937, apparently at the request of Katharine White, who was then trying out a succession of new fiction editors. Though it has passed into New Yorker legend, "Theory and Practice" was a working document and fairly reflected the magazine's guidelines and tastes of the time. [--from Genius in Disguise: Harold Ross of the New Yorker, by Thomas Kunkel (Carroll & Graf,NY 1995] THE AVERAGE CONTRIBUTOR TO THIS MAGAZINE IS SEMI-LITERATE; that is, he is ornate to no purpose, rull of senseless and elegant variations, and can be relied on to use three sentences where a word would do. It is impossible to lay down any exact and complete formula for bringing order out of this underbrush, but there are a few general rules. 1. Writers always use too damn many adverbs. On one page, recently, I found eleven modifying the verb "said": "He said morosely, violently, eloquently," and so on. Editorial theory should probably be that a writer who can't make his context indicate the way his character is talking ought to be in another line of work. Anyway, it is impossible for a character to go through all these emotional states one after the other. Lon Chancy might be able to do it, but he is dead 2. Word "said" is O.K. Efforts to avoid repetition by inserting "grunted," "snorted," etc., are waste motion, and offend the pure in heart. 3. Our writers are full of cliches, just as old barns are full of bats. -

Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn

'Memorials of great & good men who were my friends'': Portraits in the Life of Oliver Wolcott^Jn ELLEN G. MILES LIVER woLCOTT, JR. (1760-1833), like many of his contemporaries, used portraits as familial icons, as ges- Otures in political alliances, and as public tributes and memorials. Wolcott and his father Oliver Wolcott, Sr. (i 726-97), were prominent in Connecticut politics during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and the first quarter of the nineteenth. Both men served as governors of the state. Wolcott, Jr., also served in the federal administrations of George Washington and John Adams. Withdrawing from national politics in 1800, he moved to New York City and was a successful merchant and banker until 1815. He spent the last twelve years of his public life in Con- I am grateful for a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Research Opportunities Fund, which made it possible to consult manuscripts and see portraits in collecdüns in New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Haven, î lartford. and Litchfield (Connecticut). Far assistance on these trips I would like to thank Robin Frank of the Yale Universit)' Art Gallery, .'\nne K. Bentley of the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Judith Ellen Johnson and Richard Malley of the Connecticut Historical Society, as well as the society's fonner curator Elizabeth Fox, and Elizabeth M. Komhauscr, chief curator at the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford. David Spencer, a former Smithsonian Institution Libraries staff member, gen- erously assisted me with the VVolcott-Cibbs Family Papers in the Special Collectiims of the University of Oregon Library, Eugene; and tht staffs of the Catalog of American Portraits, National Portrait Ciallery, and the Inventory of American Painting. -

IMPOSSIBLE STAGE DIRECTIONS a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the School of Theatre and Dance University of Houston in Part

IMPOSSIBLE STAGE DIRECTIONS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Theatre and Dance University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Chelsea M. Taylor May 2017 IMPOSSIBLE STAGE DIRECTIONS An Abstract of a Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Theatre and Dance University of Houston In Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By Chelsea M. Taylor May 2017 ABSTRACT Stage directions that defy singular interpretation and do not, in fact, direct staging have been underexplored by simplistic theories which describe didascalia as fundamentally instructional. This thesis aims to develop methods of defining, interpreting, and staging impossible stage directions in modern and post-modern plays. I use textual analysis in tandem with the historical context of selected plays to elucidate the purpose of the stage direction within the text. Then, I use the purpose of the stage direction within the text to discover a responsible way of presenting the playwright’s work onstage. Three case studies reconstruct an impossible stage direction from a different genre, movement, or style of theatre. The first study discusses how Anton Chekhov’s breaking string in The Cherry Orchard breaks the traditional semiotic model of interpretation by combining realism and symbolism. The second study explores affect theory, as opposed to semiotics, as a means of interpreting Antonin Artaud’s nauseating apocalypse in Spurt of Blood. Lastly, I use concepts from trauma studies to hypothetically stage Heiner Müller’s radiating breast cancer in Hamletmachine as a traumatic memory. -

Journalist in Disguise St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Pix Media Spring 2009 Journalist in disguise St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Journalist in disguise" (2009). Pix Media. 54. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pix Media by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St. Norbert College Magazine - Journalist in disguise: Thomas Kunkel, president of St. Norbert College - St. Norbert College :: ACADEMIC PROGRAMS | ALUMNI | FUTURE STUDENTS | PARENTS | VISITORS (Students, faculty and staff) About SNC | A to Z Index | Directory QUICK LINKS: - Home - Magazine President's message Seven-figure gifts put athletics complex on the fast track Spring 2009 | Finding the Balance Student research goes Galapagos A short course in educationomics Economics lessons find their way to classrooms Journalist in around the world disguise: A look at Mastering the job search two books authored Finding $50 bills in the Web exclusives NFL draft by President Thomas Look here for web-only A short period of Kunkel content that expands economic growth By John Pennington, on topics presented in the An aardvark a day keeps Professor of English the doctor away current St. Norbert College Live! from Schuldes Magazine (PDF). Subscribe “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.” Dorothy Parker (1893- Student research E-newsletter 1967), American writer and goes Galapagos Television Show wit, founding member of the Reporting from one of the Press Releases Algonquin Round Table, and world’s best natural one of the original advisory laboratories. -

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection

Catalog Records April 7, 2021 6:03 PM Object Id Object Name Author Title Date Collection 1839.6.681 Book John Marshall The Writings of Chief Justice Marshall on the Federal 1839 GCM-KTM Constitution 1845.6.878 Book Unknown The Proverbs and other Remarkable Sayings of Solomon 1845 GCM-KTM 1850.6.407 Book Ik Marvel Reveries of A Bachelor or a Book of the Heart 1850 GCM-KTM The Analogy of Religion Natural and Revealed, to the 1857.6.920 Book Joseph Butler 1857 GCM-KTM Constitution and Course of Nature 1859.6.1083 Book George Eliot Adam Bede 1859 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.1 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.159.2 Book Charles Dickens The Old Curiosity Shop: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.1 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.160.2 Book Charles Dickens Nicholas Nickleby: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.162 Book Charles Dickens Great Expectations: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1867.6.163 Book Charles Dickens Christmas Books: Charles Dickens's Works 1867 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.1 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume I Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1868.6.161.2 Book Charles Dickens David Copperfield: Volume II Charles Dickens's Works 1868 GCM-KTM 1871.6.359 Book James Russell Lowell Literary Essays 1871 GCM-KTM 1876.6. -

Appendix Plays Discussed in This Book

Appendix Plays Discussed in This Book Abe Lincoln in Illinois, Robert Sherwood. 1938 Broadway run: 472 performances. 1993 Lincoln Center revival: 27 previews, 40 performances. Abraham Lincoln, John Drinkwater. 1919 Broadway run: 193 per- formances. 1929 Broadway revival: 8 performances. Abraham Lincoln’s Big Gay Dance Party, Aaron Loeb. 2008 San Francisco. 2010 off-Broadway run. American Iliad, Donald Freed. 2001 Burbank, California. As the Girls Go, William Roos (book), Jimmy McHugh (music), Harold Adamson (lyrics). 1948 Broadway run: 414 performances. Assassins, John Weidman (book), Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics). 1990 off-Broadway run: 73 performances. 1992 London revival. 2004 Broadway revival: 26 previews, 101 performances. The Best Man, Gore Vidal. 1960 Broadway run: 520 performances. 2000 Broadway revival: 15 previews, 121 performances. Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson, Alex Timbers (book), Michael Friedman (music and ly73rics). 2008 Los Angeles. 2009 and 2010 off-Broadway runs. Buchanan Dying, John Updike. 1976 Franklin and Marshall College. Bully! Jerome Alden. 1977 Broadway run: 8 previews, 8 performances. 2006 off Broadway revival. The Bully Pulpit, Michael O. Smith. 2008 off-Broadway. Camping with Henry and Tom, Mark St. Germain. 1995 off- Broadway run: 105 performances. Numerous regional theater revivals since then. An Evening with Richard Nixon, Gore Vidal. Broadway run: 14 previews, 16 performances. First Lady, Katherine Dayton and George S. Kaufman. 1935 Broadway run: 246 performances. 1952 off-Broadway revival. 1980 Berkshire Theater Festival revival. 1996 Yale Repertory Theatre revival. First Lady Suite, Michael John LaChiusa. 1993 off-Broadway run: 32 performances. Revivals include Los Angeles 2002, off Broadway 2004, and London 2009. 160 Appendix Frost/Nixon, Peter Morgan. -

Trinity Tripod, 1984-05-20

Commencement Issue The Vol. LXXXII, Issue 25 TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT May 20,1984 Honorary Degrees Awarded At Commencement Gill To Speak At Commencement Hartford, CT — Trinity College Bailyn's seven books include served as a curate in churches in will award six persons honorary two for which he received major New York before coming to Con- degrees at the College's 158th awards. The Ideologiacal Origins necticut as rector of St. Mark's Commencement Sunday, May 20, of the American Revolution won Church, Bridgeport, in 1966, 1984. the Pulitzer and Bancroft prizes where he served until 1981. He The names of the recipients in 1968, and The Ordeal of was elected a Bishop Suffragan in were announced to the faculty Thomas Hutchinson recieved a 1981, and as such has pastoral ov- May 8 by President James F. Eng- National Book Award in 1975. ersight of the western part of the lish, Jr. Bailyn was president of the diocese, from Litchfield to Green- Those to be honored are: Dr. American Historical Association wich. Bernard Bailyn, Adams Univer- in 1981. He holds honorary de- Bishop Coleridge is a Diplo- sity Professor, Harvard Univer- grees from eight colleges and uni- mate of the American Association sity; The Right Reverend Clarence versities. of Pastoral Counselors and super- N. Coleridge, Bishop Suffragan of Clarence N. Coleridge will re- vises pastoral counselors in train- the Episcopal Diocese of Con- ceive a Doctor of Divinity degree ing. He is a member of the necticut; S. Herbert Evison '12, a (D.D.). A native of Guyana, he is Academy of Certified Social conservationist; Brendan Gill, the a graduate of Howard University Workers. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

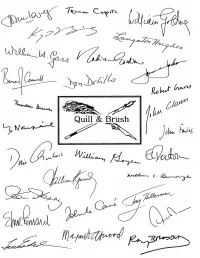

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value.