Lois Long, 1925-1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at the New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Here at The New Yorker by Brendan Gill Brendan Gill, Here in Westchester. BRONXVILLE B RENDAN GILL, the urbane drama critic for The New Yorker, is almost as hard to catch up with as the White Rabbit in “Alice in Wonderland—he's usually late for one or another important engagement. In addition to his reviewing responsibilities, Mr. Gill is the author of a biography of Charles A. Lindbergh and a book of short stories, “Ways of Loving.” He has also been a mainstay of historical‐preservation groups in the metropolitan area. A cosmopolitan suburbanite, he rises in his Bronxville here at 6 A.M., shuttles to his office in Manhattan, works through a busy day of appointments and writing, then goes off to see a play. Besides the 40 to 50 Broadway openings he attends during a season, he will see 20 to 30 Off Broadway shows and take trips to visit regional theater groups. He refuses to feel chastened by fairly widespread criticism that his memoir, “Here at The New Yorker,” is a “snobbish” book, laughing it off with the comment that “they always call me that, and I'm always indignant.” He won't be fashionably pessimistic about the future of New York City, and he won't be fashionably cynical about the virtues of suburban life. He recently completed a public lecture series at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on “Utopian Suburbs,” with talks on “Grooming the Wilderness,” about Llewellyn Park in New Jersey and Tuxedo Park in Westchester, “Parnassus by Rail,” about Lawrence Park in Bronxville and Garden City, L.I., and “Ghosts of Green Gardens,” about Forest Hills and Sunnyside in Queens. -

Full Diss Reformatted II

“NEWS THAT STAYS NEWS”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF LITERATURE, GOSSIP, AND COMMUNITY IN MODERNITY Lindsay Rebecca Starck A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Gregory Flaxman Erin Carlston Eric Downing Andrew Perrin Pamela Cooper © 2016 Lindsay Rebecca Starck ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lindsay Rebecca Starck: “News that stays news”: Transformations of Literature, Gossip, and Community in Modernity (Under the direction of Gregory Flaxman and Erin Carlston) Recent decades have demonstrated a renewed interest in gossip research from scholars in psychology, sociology, and anthropology who argue that gossip—despite its popular reputation as trivial, superficial “women’s talk”—actually serves crucial social and political functions such as establishing codes of conduct and managing reputations. My dissertation draws from and builds upon this contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship by demonstrating how the modernists incorporated and transformed the popular gossip of mass culture into literature, imbuing it with a new power and purpose. The foundational assumption of my dissertation is that as the nature of community changed at the turn of the twentieth century, so too did gossip. Although usually considered to be a socially conservative force that serves to keep social outliers in line, I argue that modernist writers transformed gossip into a potent, revolutionary tool with which modern individuals could advance and promote the progressive ideologies of social, political, and artistic movements. Ultimately, the gossip of key American expatriates (Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Janet Flanner, and Ezra Pound) became a mode of exchanging and redefining creative and critical values for the artists and critics who would follow them. -

79Th, Anaheim, CA, August 10-13, 1996)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 568 CS 215 576 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (79th, Anaheim, CA, August 10-13, 1996). Newspaper and Magazine Division. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE Aug 96 NOTE 316p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 215 568-580. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Feminism; *Journalism; *Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; *Newspapers; *Periodicals; Popular Culture; Presidential Campaigns (United States); Sex Bias; Victims of Crime IDENTIFIERS Audiotex; *Journalists; Media Bias; *Media Coverage; News Bias; News Sources; Popular Magazines ABSTRACT The Newspaper and Magazine section of the proceedings contains the following 11 papers: "Real-Time Journalism: Instantaneous Change for News Writing" (Karla Aronson and others); "Names in the News: A Study of Journalistic Decision-Making in Regard to the Naming of Crime Victims" (Michelle Johnson); "The Daily Newspaper and Audiotex Personals: A Case Study of Organizational Adoption of Innovation" (Debra Merskin); "What Content Shows about Topic-Team Performance" (John T. Russial); "Have You Heard the News? Newspaper Journalists Consider Audiotex and Other New Media Forms" (Jane B. Singer); "Who Reports the Hard/Soft News? A Study of Differences in Story Assignments to Male and Female Journalists at 'Newsweek'" (Dan Alinanger); "Welcome to Lilliput: The Shrinking of the General Interest in Magazine Publishing" (Erik Ellis); "The Retiring Feminist: Doris E. Fleischman and Doris Fleischman Bernays" (Susan Henry); "'Of Enduring Interest': The First Issue of 'The Readers Digest' as a 'Snapshot' of America in 1922--and its Legacy in a Mass-Market Culture" (Carolyn Kitch); "News Magazine Lead Story Coverage of the 1992 Presidential Campaign" (Mark N. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1975 VOL. XIX NO. 4 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Spiro K. Kostof, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Assistant Editor: Elisabeth W. Potter, 22927 Edmonds Way, Edmonds, Washington, 98020 SAH NOTICES the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology of the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology ... 1976 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (May 19-24). Marian C. HYMAN MYERS AND GEORGE THOMAS organized an ex Donnelly, general chairman; Charles E. Peterson, FAIA, honor hibition of photographs, original drawings, hardware, and ary local chairman; and R. Damon Childs, local chairman. The plans of restoration work now in progress at the Pennsylvania call for papers appeared in the April Newsletter. Academy of Fine Arts designed by Furness and Hewitt. Shown at the AlA Gallery in Philadelphia last month, the exhibition 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles (with College Art Associa material was drawn from private collections as well as those of tion) - February 2-7. Adolf K. Placzek, Columbia University, the Academy and the Philadelphia Museum of Art ... EVA D. is general chairman of the meeting. David S. Gebhard, Univer NOLL addressed the annual meeting of the Chester County sity of California, Santa Barbara, will act as local chairman. Historical Society last May on the subject of "Communica The call for papers appeared in the June Newsletter. tions Between the Colonies." Mrs. Noll, who is historian for Project 1776 sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission of 1975 Annual Tour- Annapolis and Southern Maryland (Octo Pennsylvania, spoke the preceding month in Pittsburgh at the ber 1-5). -

Journalist in Disguise St

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Pix Media Spring 2009 Journalist in disguise St. Norbert College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia Recommended Citation St. Norbert College, "Journalist in disguise" (2009). Pix Media. 54. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/pixmedia/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pix Media by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. St. Norbert College Magazine - Journalist in disguise: Thomas Kunkel, president of St. Norbert College - St. Norbert College :: ACADEMIC PROGRAMS | ALUMNI | FUTURE STUDENTS | PARENTS | VISITORS (Students, faculty and staff) About SNC | A to Z Index | Directory QUICK LINKS: - Home - Magazine President's message Seven-figure gifts put athletics complex on the fast track Spring 2009 | Finding the Balance Student research goes Galapagos A short course in educationomics Economics lessons find their way to classrooms Journalist in around the world disguise: A look at Mastering the job search two books authored Finding $50 bills in the Web exclusives NFL draft by President Thomas Look here for web-only A short period of Kunkel content that expands economic growth By John Pennington, on topics presented in the An aardvark a day keeps Professor of English the doctor away current St. Norbert College Live! from Schuldes Magazine (PDF). Subscribe “I don’t care what is written about me so long as it isn’t true.” Dorothy Parker (1893- Student research E-newsletter 1967), American writer and goes Galapagos Television Show wit, founding member of the Reporting from one of the Press Releases Algonquin Round Table, and world’s best natural one of the original advisory laboratories. -

Genêt Unmasked : Examining the Autobiographical in Janet Flanner

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OPUS: Open Uleth Scholarship - University of Lethbridge Research Repository University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Theses Arts and Science, Faculty of 2006 Genêt unmasked : examining the autobiographical in Janet Flanner Gaudette, Stacey Leigh Lethbridge, Alta. : University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Arts and Science, 2006 http://hdl.handle.net/10133/531 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS GENÊT UNMASKED: EXAMINING THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IN JANET FLANNER STACEY LEIGH GAUDETTE Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Stacey Leigh Gaudette, 2006 GENÊT UNMASKED: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IN JANET FLANNER STACEY LEIGH GAUDETTE Approved: • (Print Name) (Signature) (Rank) (Highest Degree) (Date) • Supervisor • Thesis Examination Committee Member • External Examiner • Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ii Abstract This thesis examines Janet Flanner, an expatriate writer whose fiction and journalism have been essential to the development of American literary modernism in that her work, taken together, comprises a remarkable autobiographical document which records her own unique experience of the period while simultaneously contributing to its particular aesthetic mission. Although recent discussions have opened debate as to how a variety of discourses can be read as autobiographical, Flanner’s fifty years worth of cultural, political, and personal observation requires an analysis which incorporates traditional and contemporary theories concerning life-writing. Essentially, autobiographical scholarship must continue to push the boundaries of analysis, focusing on the interactions and reactions between the outer world and the inner self. -

Trinity Tripod, 1984-05-20

Commencement Issue The Vol. LXXXII, Issue 25 TRINITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT May 20,1984 Honorary Degrees Awarded At Commencement Gill To Speak At Commencement Hartford, CT — Trinity College Bailyn's seven books include served as a curate in churches in will award six persons honorary two for which he received major New York before coming to Con- degrees at the College's 158th awards. The Ideologiacal Origins necticut as rector of St. Mark's Commencement Sunday, May 20, of the American Revolution won Church, Bridgeport, in 1966, 1984. the Pulitzer and Bancroft prizes where he served until 1981. He The names of the recipients in 1968, and The Ordeal of was elected a Bishop Suffragan in were announced to the faculty Thomas Hutchinson recieved a 1981, and as such has pastoral ov- May 8 by President James F. Eng- National Book Award in 1975. ersight of the western part of the lish, Jr. Bailyn was president of the diocese, from Litchfield to Green- Those to be honored are: Dr. American Historical Association wich. Bernard Bailyn, Adams Univer- in 1981. He holds honorary de- Bishop Coleridge is a Diplo- sity Professor, Harvard Univer- grees from eight colleges and uni- mate of the American Association sity; The Right Reverend Clarence versities. of Pastoral Counselors and super- N. Coleridge, Bishop Suffragan of Clarence N. Coleridge will re- vises pastoral counselors in train- the Episcopal Diocese of Con- ceive a Doctor of Divinity degree ing. He is a member of the necticut; S. Herbert Evison '12, a (D.D.). A native of Guyana, he is Academy of Certified Social conservationist; Brendan Gill, the a graduate of Howard University Workers. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

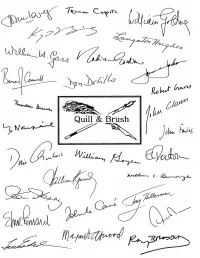

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: a Conversation with Gordon Rogoff

Fall 2010 99 The Elusive Object and the Fading Craft of Theatre Criticism: A Conversation with Gordon Rogoff Bert Cardullo A cofounder and editor of Encore Magazine (London) in the 1950s and Administrative Director of The Actors’ Studio, New York (1959-1962), Gordon Rogoff (1931-) was a dramaturg with The Open Theatre during the 1960s. He is Professor Emeritus at Brooklyn College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY), and Professor of Dramaturgy and Dramatic Criticism at the Yale School of Drama, a position he assumed in 1987. He has been Associate Dean of the Yale School of Drama (1966-1969), chair of two departments of drama (State University of New York [SUNY] at Buffalo and Brooklyn College of CUNY), and Adjunct Professor of Humanities at The Cooper Union. From 1995-1999, he was Co-Director of Exiles, a school for theatre training in Ireland. Mr. Rogoff has directed plays Off-Broadway and in Chicago, as well as in Williamstown and Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He directed his own adaptation of six stories from Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, in Buffalo, New York, and Off- Broadway. In 1976, he won an Obie Award for his direction of Morton Lichter’s Old Timers’ Sexual Symphony (and Other Notes). His honors include a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Morton Dauwen Zabel Award of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. He has contributed numerous essays and reviews to such periodicals as American Theatre, Theater, The Village Voice, Parnassus, The New Republic, The Nation, and Plays and Players. -

The First Issue of the New Yorker Appeared on February 21,1925

He had liked working on a publication that was written The first issue of The New for a small, well-defined group of readers—in that case, Yorker appeared on February soldiers—by a similarly small and well-defined group, 21,1925. Afterthe fashion of also soldiers. After the war he wanted to continue in Vanity Fair, which also the same vein; he imagined a magazine, written for a disdained what it called small community, that would present information “hon the “old lady from Du estly” without inflated rhetoric and without paying buque,” or provincial mo homage to conventional pieties. rality, The New Yorker Having tried unsuccessfully to do this with Home announced itself as the Sector, he had wandered from the American Legion voice of the young, the fit, Weekly to the humor magazine Judge. But he remained the urbane, the cognos determined to start something different. Impressed by centi: “It hopes to reflect the repartee of his Algonquin round table compatriots the metropolitan life, to and perspicacious enough to consider exploiting their keep up with events and af wit in his own venture, he found a backer in Raoul fairs of the day, to be gay, hu Fleischmann, one of the occasional Algonquinites who morous, satirical but to be more frequented their card party, the Thanatopsis Poker and than just a jester. It will publish Frank Flanner. Inside Straight Club. Fleischmann’s father had in facts that it will have to go behind the John Monhoff vented the “breadline,” both word and concept, by giv scenes to get, but it will not deal in scandal for the sake ing away each day’s unsold of scandal nor sensation for the sake of sensation. -

Mystic Mah Jong

Mystic Mah Jong Mystic Mah Jong 9 Agata Stanford A Jenevacris Press Publication Mystic Mah Jong A Dorothy Parker Mystery / June 2011 Published by Jenevacris Press New York This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. 7 All rights reserved Copyright © 2011 by Agata Stanford Edited by Shelley Flannery Typesetting & Cover Design by Eric Conover ISBN 978-0-9827542-5-2 Printed in the United States of America www.dorothyparkermysteries.com For my husband, Richard. Also by Agata Stanford The Dorothy Parker Mysteries Series: The Broadway Murders Chasing the Devil vii Contents Cast of Characters … ... ... … … … … … Page ix Chapter One … … ... … … … … … … … Page 1 Chapter Two … … ... … … … … … … … Page 53 Chapter Three … … … … … … … … … Page 89 Chapter Four … … ... … … … … … … … Page 109 Chapter Five … … ... … … … … … … … Page 153 Chapter Six … … ... … … … … … … … Page 165 Chapter Seven … … … … … … … … … Page 203 Chapter Eight … … … … … … … … … Page 227 Chapter Nine … … … … … … … … … Page 253 Chapter Ten ... … … … … … … … … … Page 299 Chapter Eleven … … … … … … … … Page 316 Chapter Twelve … … … … … … … … Page 381 The Final Chapter … ... … … … … … … Page 417 Glossary of British Slang ... … … … … … Page 431 Glossary of American Slang… … … … … Page 435 About the Author … … ... … … … … … Page 438 9 ix Who’s Who in the Cast of Dorothy Parker Mysteries The Algonquin Round Table was the famous as- semblage of writers, artists, actors, musicians, newspaper and magazine reporters, columnists, and critics who met for luncheon at one P.M. most days, for a period of about ten years, starting in 1919, in the Rose Room of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan. -

The Publication of “Hiroshima” in the New Yorker

Steve Rothman HSCI E-196 Science and Society in the 20th Century Professor Everett Mendelsohn January 8, 1997 The Publication of “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker Overview A year after World War II ended, a leading American weekly magazine published a striking description of what life was like for those who survived a nuclear attack. The article, simply titled “Hiroshima,” was published by The New Yorker in its August 31, 1946 issue. The thirty-one thousand word article displaced virtually all other editorial matter in the issue. “Hiroshima” traced the experiences of six residents who survived the blast of August 6, 1945 at 8:15 am. There was a personnel clerk, Miss Toshiko Sasaki; a physician, Dr. Masakazu Fujii; a tailor’s widow with three small children, Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura; a German missionary priest, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge; a young surgeon, Dr. Terufumi Sasaki; and a Methodist pastor, the Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto. The article told the story of their experiences, starting from when the six woke up that morning, to what they were doing the moment of the blast and the next few hours, continuing through the next several days and then ending with the situations of the six survivors several months later. The article, written by John Hersey, created a blast of its own in the publishing world. The New Yorker sold out immediately, and requests for reprints poured in from all over the world. Following publication, “Hiroshima” was read on the radio in the United States and abroad. Other magazines S. Rothman page 2 reviewed the article and referred their readers to it.