The First Issue of the New Yorker Appeared on February 21,1925

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Diss Reformatted II

“NEWS THAT STAYS NEWS”: TRANSFORMATIONS OF LITERATURE, GOSSIP, AND COMMUNITY IN MODERNITY Lindsay Rebecca Starck A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Gregory Flaxman Erin Carlston Eric Downing Andrew Perrin Pamela Cooper © 2016 Lindsay Rebecca Starck ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Lindsay Rebecca Starck: “News that stays news”: Transformations of Literature, Gossip, and Community in Modernity (Under the direction of Gregory Flaxman and Erin Carlston) Recent decades have demonstrated a renewed interest in gossip research from scholars in psychology, sociology, and anthropology who argue that gossip—despite its popular reputation as trivial, superficial “women’s talk”—actually serves crucial social and political functions such as establishing codes of conduct and managing reputations. My dissertation draws from and builds upon this contemporary interdisciplinary scholarship by demonstrating how the modernists incorporated and transformed the popular gossip of mass culture into literature, imbuing it with a new power and purpose. The foundational assumption of my dissertation is that as the nature of community changed at the turn of the twentieth century, so too did gossip. Although usually considered to be a socially conservative force that serves to keep social outliers in line, I argue that modernist writers transformed gossip into a potent, revolutionary tool with which modern individuals could advance and promote the progressive ideologies of social, political, and artistic movements. Ultimately, the gossip of key American expatriates (Henry James, Djuna Barnes, Janet Flanner, and Ezra Pound) became a mode of exchanging and redefining creative and critical values for the artists and critics who would follow them. -

Surreal Visual Humor and Poster

Fine Arts Status : Review ISSN: 1308 7290 (NWSAFA) Received: January 2016 ID: 2016.11.2.D0176 Accepted: April 2016 Doğan Arslan Istanbul Medeniyet University, [email protected], İstanbul-Turkey http://dx.doi.org/10.12739/NWSA.2016.11.2.D0176 HUMOR AND CRITICISM IN EUROPEAN ART ABSTRACT This article focused on the works of Bosh, Brughel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön and Kubin, lived during and after the Renaissance, whose works contain humor and criticism. Although these artists lived in from different cultures and societies, their common tendencies were humor and criticism in their works. Due to the conditions of the period where these artists lived in, their artistic technic and style were different from each other, which effected humor and criticism in the works too. Analyzes and comments in this article are expected to provide information regarding the humor and criticism of today’s Europe. This research will indicate solid information regarding humor and tradition of criticism in Europe through comparisons and comments on the works of the artists. It is believed that, this research is considered to be useful for academicians, students, artists and readers who interested in humour and criticism in Europe. Keywords: Humour, Criticism, Bosch, Gillray, Grandville AVRUPA SANATINDA MİZAH VE ELEŞTİRİ ÖZ Bu makale, Avrupa Rönesans sanatı dönemi ve sonrasında yaşamış Bosch, Brueghel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön ve Kubin gibi önemli sanatçıların çalışmalarında görülen mizah ve eleştiri üzerine kurgulanmıştır. Bahsedilen sanatçılar farklı toplum ve kültürde yaşamış olmasına rağmen, çalışmalarında ortak eğilim mizah ve eleştiriydi. Sanatçıların bulundukları dönemin şartları gereği çalışmalarındaki farklı teknik ve stiller, doğal olarak mizah ve eleştiriyi de etkilemiştir. -

Research.Pdf (1.328Mb)

VISUAL HUMOR: FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS AND MODERN AMERICAN WOMANHOOD, 1860- 1915 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Meghan McClellan Dr. Kristin Schwain, Dissertation Advisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Meghan McClellan 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled Visual Humor: Female Photographers and the Making of Modern American Womanhood, 1860-1915 presented by Meghan McClellan, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Kristin Schwain Dr. James Van Dyke Dr. Michael Yonan Dr. Alex Barker To Marsha Thompson and Maddox Thornton ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The difficulty of writing a dissertation was never far from anyone’s lips in graduate school. We all talked about the blood, sweat, and tears that went into each of our projects. What we also knew was the unrelenting support our loved ones showed us day in and day out. These acknowledgments are for those who made this work possible. This dissertation is a testament to perseverance and dedication. Yet, neither of those were possible without a few truly remarkable individuals. First, thank you to all my committee members: Dr. Alex Barker, Dr. Michael Yonan, and Dr. James Van Dyke. Your input and overall conversations about my project excited and pushed me to the end. Thank you Mary Bixby for giving me the “tough love” I needed to make sure I met my deadlines. -

79Th, Anaheim, CA, August 10-13, 1996)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 568 CS 215 576 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (79th, Anaheim, CA, August 10-13, 1996). Newspaper and Magazine Division. INSTITUTION Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. PUB DATE Aug 96 NOTE 316p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 215 568-580. PUB TYPE Collected Works Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Feminism; *Journalism; *Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; *Newspapers; *Periodicals; Popular Culture; Presidential Campaigns (United States); Sex Bias; Victims of Crime IDENTIFIERS Audiotex; *Journalists; Media Bias; *Media Coverage; News Bias; News Sources; Popular Magazines ABSTRACT The Newspaper and Magazine section of the proceedings contains the following 11 papers: "Real-Time Journalism: Instantaneous Change for News Writing" (Karla Aronson and others); "Names in the News: A Study of Journalistic Decision-Making in Regard to the Naming of Crime Victims" (Michelle Johnson); "The Daily Newspaper and Audiotex Personals: A Case Study of Organizational Adoption of Innovation" (Debra Merskin); "What Content Shows about Topic-Team Performance" (John T. Russial); "Have You Heard the News? Newspaper Journalists Consider Audiotex and Other New Media Forms" (Jane B. Singer); "Who Reports the Hard/Soft News? A Study of Differences in Story Assignments to Male and Female Journalists at 'Newsweek'" (Dan Alinanger); "Welcome to Lilliput: The Shrinking of the General Interest in Magazine Publishing" (Erik Ellis); "The Retiring Feminist: Doris E. Fleischman and Doris Fleischman Bernays" (Susan Henry); "'Of Enduring Interest': The First Issue of 'The Readers Digest' as a 'Snapshot' of America in 1922--and its Legacy in a Mass-Market Culture" (Carolyn Kitch); "News Magazine Lead Story Coverage of the 1992 Presidential Campaign" (Mark N. -

Genêt Unmasked : Examining the Autobiographical in Janet Flanner

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OPUS: Open Uleth Scholarship - University of Lethbridge Research Repository University of Lethbridge Research Repository OPUS http://opus.uleth.ca Theses Arts and Science, Faculty of 2006 Genêt unmasked : examining the autobiographical in Janet Flanner Gaudette, Stacey Leigh Lethbridge, Alta. : University of Lethbridge, Faculty of Arts and Science, 2006 http://hdl.handle.net/10133/531 Downloaded from University of Lethbridge Research Repository, OPUS GENÊT UNMASKED: EXAMINING THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IN JANET FLANNER STACEY LEIGH GAUDETTE Bachelor of Arts, University of Lethbridge, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies of the University of Lethbridge in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of English University of Lethbridge LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA, CANADA © Stacey Leigh Gaudette, 2006 GENÊT UNMASKED: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL IN JANET FLANNER STACEY LEIGH GAUDETTE Approved: • (Print Name) (Signature) (Rank) (Highest Degree) (Date) • Supervisor • Thesis Examination Committee Member • External Examiner • Chair, Thesis Examination Committee ii Abstract This thesis examines Janet Flanner, an expatriate writer whose fiction and journalism have been essential to the development of American literary modernism in that her work, taken together, comprises a remarkable autobiographical document which records her own unique experience of the period while simultaneously contributing to its particular aesthetic mission. Although recent discussions have opened debate as to how a variety of discourses can be read as autobiographical, Flanner’s fifty years worth of cultural, political, and personal observation requires an analysis which incorporates traditional and contemporary theories concerning life-writing. Essentially, autobiographical scholarship must continue to push the boundaries of analysis, focusing on the interactions and reactions between the outer world and the inner self. -

The Ideological Discourse of the Islamist Humor Magazines in Turkey: the Case of Misvak

THE IDEOLOGICAL DISCOURSE OF THE ISLAMIST HUMOR MAGAZINES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF MISVAK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NAZLI HAZAL TETİK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Barış Çakmur Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assist. Prof. Dr. Özgür Avcı (METU, PADM) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, PADM) Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., ILF) PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Nazlı Hazal Tetik Signature: iii ABSTRACT THE IDEOLOGICAL DISCOURSE OF THE ISLAMIST HUMOR MAGAZINES IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF MISVAK Tetik, Nazlı Hazal M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan July 2020, 259 pages This thesis focuses on the ideological discourse of Misvak, one of the most popular Islamist humor magazines in Turkey in the 2000s. -

1 for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Sloane Crosley, Associate Director of Publicity Phone

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Sloane Crosley, Associate Director of Publicity Phone: 212.572.2016 E-mail: [email protected] VINTAGE BOOKS TO PUBLISH NIGHTLIGHT: A TWILIGHT PARODY AS A VINTAGE ORIGINAL IN TIME FOR THE MAJOR MOTION PICTURE RELEASE OF TWILIGHT SEQUEL” NEW MOON” New York, NY 10/05/09: Vintage Books announces the publication of the first Harvard Lampoon novel parody in exactly 40 years. In 1969, The Harvard Lampoon took affectionate aim at a massive pop culture phenomenon with Bored of the Rings. The paperback original Nightlight, a pitch-perfect spin on the Stephanie Meyers series, will be available on NOVEMBER 3RD. The Twilight movie sequel, “New Moon,” arrives in theaters on November 20th. “Funny” might get you a blog post these days, but it’s the Lampoon-level of satire that makes Nightlight worth every pseudo-bloodsucking, angst-ridden page. Nightlight stakes at the heart of what makes Twilight tick…or, really, cuts to the core of it. As demonstrated by the cover of the book. Or takes a bite out of it, as also demonstrated by the cover of the book. Brooding and hilarious, let Nightlight be your guide through the Twilight fandom that has eclipsed the mind of every teenager you have ever met. About the Plot Pale and klutzy, Belle Goose arrives in Switchblade, Oregon looking for adventure, or at least an undead classmate. She soon discovers Edwart Mullen, a super-hot computer nerd with zero interest in girls. After witnessing a number of strange events–Edwart leaves his Tater Tots™ untouched at lunch! Edwart saves her from a flying snowball!–Belle has a dramatic revelation: Edwart is a vampire. -

Analyzing Dave Barry's Writing His Influences and the Traits He Shares with the Past Century's Newspaper Humorists

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 "I am not making this up!": Analyzing Dave Barry's writing his influences and the traits he shares with the past century's newspaper humorists Nathaniel M. Cerf The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cerf, Nathaniel M., ""I am not making this up!": Analyzing Dave Barry's writing his influences and the traits he shares with the past century's newspaper humorists" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5089. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5089 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Monnttainia Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. !*Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ___ No, I do not grant permission ___ Author's Signature: Date:_ i z / n / w s _____________ / Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 “I AM NOT MAKING THIS UP!”: ANALYZING DAVE BARRY’S WRITING, HIS INFLUENCES AND THE TRAITS HE SHARES WITH THE PAST CENTURY’S NEWSPAPER HUMORISTS by Nathaniel M. -

Humour and Laughter in History

Elisabeth Cheauré, Regine Nohejl (eds.) Humour and Laughter in History Historische Lebenswelten in populären Wissenskulturen History in Popular Cultures | Volume 15 Editorial The series Historische Lebenswelten in populären Wissenskulturen | History in Popular Cultures provides analyses of popular representations of history from specific and interdisciplinary perspectives (history, literature and media studies, social anthropology, and sociology). The studies focus on the contents, media, genres, as well as functions of contemporary and past historical cultur- es. The series is edited by Barbara Korte and Sylvia Paletschek (executives), Hans- Joachim Gehrke, Wolfgang Hochbruck, Sven Kommer and Judith Schlehe. Elisabeth Cheauré, Regine Nohejl (eds.) Humour and Laughter in History Transcultural Perspectives Our thanks go to the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsge- meinschaft) for supporting and funding the project. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-2858-0. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

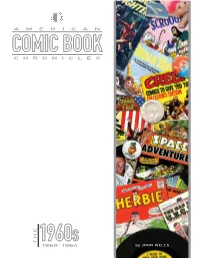

A M E R I C a N C H R O N I C L E S the by JOHN WELLS 1960-1964

AMERICAN CHRONICLES THE 1960-1964 byby JOHN JOHN WELLS Table of Contents Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chroncles ........ 4 Note on Comic Book Sales and Circulation Data......................................................... 5 Introduction & Acknowlegments................................. 6 Chapter One: 1960 Pride and Prejudice ................................................................... 8 Chapter Two: 1961 The Shape of Things to Come ..................................................40 Chapter Three: 1962 Gains and Losses .....................................................................74 Chapter Four: 1963 Triumph and Tragedy ...........................................................114 Chapter Five: 1964 Don’t Get Comfortable ..........................................................160 Works Cited ......................................................................214 Index ..................................................................................220 Notes Introductory Note about the Chronological Structure of American Comic Book Chronicles The monthly date that appears on a comic book head as most Direct Market-exclusive publishers cover doesn’t usually indicate the exact month chose not to put cover dates on their comic books the comic book arrived at the newsstand or at the while some put cover dates that matched the comic book store. Since their inception, American issue’s release date. periodical publishers—including but not limited to comic book publishers—postdated -

Mystic Mah Jong

Mystic Mah Jong Mystic Mah Jong 9 Agata Stanford A Jenevacris Press Publication Mystic Mah Jong A Dorothy Parker Mystery / June 2011 Published by Jenevacris Press New York This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. 7 All rights reserved Copyright © 2011 by Agata Stanford Edited by Shelley Flannery Typesetting & Cover Design by Eric Conover ISBN 978-0-9827542-5-2 Printed in the United States of America www.dorothyparkermysteries.com For my husband, Richard. Also by Agata Stanford The Dorothy Parker Mysteries Series: The Broadway Murders Chasing the Devil vii Contents Cast of Characters … ... ... … … … … … Page ix Chapter One … … ... … … … … … … … Page 1 Chapter Two … … ... … … … … … … … Page 53 Chapter Three … … … … … … … … … Page 89 Chapter Four … … ... … … … … … … … Page 109 Chapter Five … … ... … … … … … … … Page 153 Chapter Six … … ... … … … … … … … Page 165 Chapter Seven … … … … … … … … … Page 203 Chapter Eight … … … … … … … … … Page 227 Chapter Nine … … … … … … … … … Page 253 Chapter Ten ... … … … … … … … … … Page 299 Chapter Eleven … … … … … … … … Page 316 Chapter Twelve … … … … … … … … Page 381 The Final Chapter … ... … … … … … … Page 417 Glossary of British Slang ... … … … … … Page 431 Glossary of American Slang… … … … … Page 435 About the Author … … ... … … … … … Page 438 9 ix Who’s Who in the Cast of Dorothy Parker Mysteries The Algonquin Round Table was the famous as- semblage of writers, artists, actors, musicians, newspaper and magazine reporters, columnists, and critics who met for luncheon at one P.M. most days, for a period of about ten years, starting in 1919, in the Rose Room of the Algonquin Hotel on West 44th Street in Manhattan. -

Mizzoualumnimagsummer2006

ow me Student jokesters tickled funny bones as they ruffled feathers. Missouri Showme covers caused a stir with themes such as the " Election Issue," the "Sex Issue" and the "Hangover Issue." Not shown are such doozies as the "Get Your Hand Out of My Stocking, It Isn't Christmas Yet Issue." For more Showme gags - in cartoon and joke form - see the following pages. 16 111 ZZO I SUMMER 2006 ith a sly wink and a salacious nudge, Wthe long-gone campus humor magazine Missouri Showme tried just about everything to unn get Mizzou students to crack a smile. Funny thing, though - MU bigwigs weren't amused. Story by John Beahler More than one Showme editor paid a visit to the dean's woodshed, and gaps in the magazine's archives testify to all the times administrators suspended publication during its on-again, off-again existence from 1920 through the early 1960s. SUMMER 2006 HIZZ OU 17 he campu brass may have Middle bush - Showme writers delighted T frowned on Showme, but Mizzou in calling the president "Centershrub" tudent got the joke. After all, - that the campus publications board had why wouldn't sophomoric humor appeal to dismissed another editor. "We will always ophomores - and to freshmen, juniors and have trouble with Showme, I am sure," Brady eniors? Showme's writers milked campus wrote, "but we may be able, gradually, to sacred cows for laughs. Its cartoons glee change its nature." Not a chance; the staff fully pointed out that not only did the was having too much fun. emperor have no clothes, but he al o had a pimple on his rear end.