Humour and Laughter in History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAPRI È...A Place of Dream. (Pdf 2,4

Posizione geografica Geographical position · Geografische Lage · Posición geográfica · Situation géographique Fra i paralleli 40°30’40” e 40°30’48”N. Fra i meridiani 14°11’54” e 14°16’19” Est di Greenwich Superficie Capri: ettari 400 Anacapri: ettari 636 Altezza massima è m. 589 Capri Giro dell’isola … 9 miglia Clima Clima temperato tipicamente mediterraneo con inverno mite e piovoso ed estate asciutta Between parallels Zwischen den Entre los paralelos Entre les paralleles 40°30’40” and 40°30’48” Breitenkreisen 40°30’40” 40°30’40”N 40°30’40” et 40°30’48” N N and meridians und 40°30’48” N Entre los meridianos Entre les méridiens 14°11’54” and 14°16’19” E Zwischen den 14°11’54” y 14°16’19” 14e11‘54” et 14e16’19“ Area Längenkreisen 14°11’54” Este de Greenwich Est de Greenwich Capri: 988 acres und 14°16’19” östl. von Superficie Surface Anacapri: 1572 acres Greenwich Capri: 400 hectáreas; Capri: 400 ha Maximum height Fläche Anacapri: 636 hectáreas Anacapri: 636 ha 1,920 feet Capri: 400 Hektar Altura máxima Hauter maximum Distances in sea miles Anacapri: 636 Hektar 589 m. m. 589 from: Naples 17; Sorrento Gesamtoberfläche Distancias en millas Distances en milles 7,7; Castellammare 13; 1036 Hektar Höchste marinas marins Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; Erhebung über den Nápoles 17; Sorrento 7,7; Naples 17; Sorrento 7,7; lschia 16; Positano 11 Meeresspiegel: 589 Castellammare 13; Castellammare 13; Amalfi Distance round the Entfernung der einzelnen Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; 17,5 Salerno 25; lschia A Place of Dream island Orte von Capri, in Ischia 16; Positano 11 16; Positano 11 9 miles Seemeilen ausgedrükt: Vuelta a la isla por mar Tour de l’ île par mer Climate Neapel 17, Sorrento 7,7; 9 millas 9 milles Typical moderate Castellammare 13; Amalfi Clima Climat Mediterranean climate 17,5; Salerno 25; lschia templado típicamente Climat tempéré with mild and rainy 16; Positano 11 mediterráneo con typiquement Regione Campania Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali winters and dry summers. -

TOUR COMBINATO CAPRI-POMPEI Contatti: [email protected] / Whatsapp: +44 (0) 7507 629016

TOUR COMBINATO CAPRI-POMPEI Contatti: [email protected] / WhatsApp: +44 (0) 7507 629016 LA TUA ESPERIENZA Cosa ti attende Scopri in un giorno i siti più visitati della regione Passeggia per le vie dello shopping di Capri Visita i Giardini di Augusto e scatta le foto dei Faraglioni Passeggia per le strade della città eterna di Pompei Cosa visiterai durante il tour combinato Capri-Pompei Visita i più famosi siti della regione in un giorno! Il tour inizierà dalla famosa “piazzetta”di Capri che raggiungerai con la funicolare. Da qui, camminerete lungo i caratteristici vicoletti dell’isola famosa per i numerosi negozi di famosissime case di moda nazionali ed internazionali e le tradizionali botteghe di artigiani. Poco distante dalla piazzetta, troverai i giardini di Augusto che nel 1900 erano la dimora estiva del famoso Friedrich Alfred Krupp. Lungo la strada, vedrai una via piccola e tortuosa che prende il suo nome: via Krupp. Da qui potrai ammirare i rinominati “Faraglioni”. Capri, uno dei luoghi più alla moda in Italia, ti offrirà un’esperienza unica! Durante l’epoca romana, gli imperatori camminavano lungo le coste incontaminate; oggi, potrai essere anche tu spettatore di uno dei panorami più mozzafiato al mondo. Dopo il tempo libero del pranzo tornerai al porto di Napoli dove, a bordo di un veicolo, raggiungerai gli scavi archeologici di Pompei. Qui potrai vivere un viaggio nel passato alla scoperta degli stili di vita, usi e abitudini degli abitanti dell’antica città romana. Vedrai i bagni termali, gli affreschi del Lupanare, il Macellum e la Basilica. Questo tour ti permetterà di vivere un’esperienza fantastica in due luoghi favolosi, di fama internazionale, che meritano assolutamente di essere visitati. -

Laughter: the Best Medicine?

Laughter: The Best Medicine? by Barbara Butler elcome to a crash COLI~SCin c~onsecli1~11cc.~ol'nvgarivc emotions. Third, Oregon Institute ofMarine Biology Gelotology 101. That isn't a using Iiumor as :I c~ol)irigs(r:itcgy n~ayalso University of Oregon typo, Gelotology (from the I~enefithealth inclirec.tly I)y moderating ad- Greek root gelos (to laugh)), is a term verse effects of stress. Finally, humor may coined in 1964 by Dr. Edith Trager and Dr. provide another indirect Ixnefit to health W.F. Fry to describe the scientific study of by increasing one's level of social support laughter. While you still can't locate this (Martin, 2002, 2004). term in the OED, you can find it on the Web. The study of humor is a science, The physiology of humor and laughter researchers publish in the Dr. William F. Fry from Stanford University psychological and physiological literature has published a number of studies of the as well as subject specific journals (e.g., physiological processes that occur dur- Humor: International Journal of Humor ing laughter and is often cited by people Research). claiming that laughter is equivalent to ex- While at the Special Libraries As- ercise. Dr. Fry states, "I believe that we do sociation annual conference last June, I not laugh merely with our lungs, or chest was able to attend a session by Elaine M. muscles, or diaphragm, or as a result of a Lundberg called Laugh For the Health of stimulation of our cardiovascular activity. It. The room was packed and she had the I believe that we laugh with our whole audience laughing and learning for the physical being. -

Saisonprogramm 2019/20

19 – 20 ZWISCHEN Vollendeter HEIMAT Genuss TRADITION braucht ein & BRAUCHTUM perfektes MODERNE Zusammenspiel KULTURRÄUME NATIONEN Als führendes Energie- und Infrastrukturunternehmen im oberösterreichischen Zentralraum sind wir ein starker Partner für Wirtschaft, Kunst und Kultur und die Menschen in der Region. Die LINZ AG wünscht allen Besucherinnen und Besuchern beste Unterhaltung. LINZ AG_Brucknerfest 190x245 mit 7mm Bund.indd 1 30.01.19 09:35 6 Vorworte 12 Saison 19/20 16 Abos 19/20 22 Das Große Abonnement 32 Sonntagsmatineen 42 Kost-Proben 44 Das besondere Konzert 100 Moderierte Foyer-Konzerte am Sonntagnachmittag 50 Chorkonzerte 104 Musikalischer Adventkalender 54 Liederabende 112 BrucknerBeats 58 Streichquartette 114 Russische Dienstage INHALTS- 62 Kammermusik 118 Musik der Völker 66 Stars von morgen 124 Jazz 70 Klavierrecitals 130 BRUCKNER’S Jazz 74 C. Bechstein Klavierabende 132 Gemischter Satz 80 Orgelkonzerte VERZEICHNIS 134 Comedy.Music 84 Orgelmusik zur Teatime 138 Serenaden 88 WortKlang 146 Kooperationen 92 Ars Antiqua Austria 158 Jugend 96 Hier & Jetzt 162 Kinder 178 Kalendarium 193 Team Brucknerhaus 214 Saalpläne 218 Karten & Service 5 Kunst und Kultur sind anregend, manchmal im flüge unseres Bruckner Orchesters genießen Hommage an das Genie Anton Bruckner Das neugestaltete Musikprogramm erinnert wahrsten Sinn des Wortes aufregend – immer kann. Dass auch die oberösterreichischen Linz spielt im Kulturleben des Landes Ober- ebenso wie das Brucknerfest an das kompo- aber eine Bereicherung unseres Lebens, weil Landesmusikschulen immer wieder zu Gast österreich ohne Zweifel die erste Geige. Mit sitorische Schaffen des Jahrhundertgenies sie die Kraft haben, über alle Unterschiedlich- im Brucknerhaus Linz sind, ist eine weitere dem internationalen Brucknerfest, den Klang- Bruckner, für den unsere Stadt einen Lebens- keiten hinweg verbindend zu wirken. -

Anacapri Capri

Informaciones turisticas Informaciones turísticas Oficina de objetos perdidos Oficina de Turismo Azienda Autonoma Cura CAPRI · 081 8386203 · ANACAPRI · 081 8387220 Soggiorno e Turismo Isola di Capri CAPRI · Piazzetta Ignazio Cerio 11 Correos, telégrafos www.capritourism.com · www.infocapri.mobi CAPRI · Via Roma, 50 · 081 9785211 081 8370424 · 8375308 · Fax 081 8370918 MARINA GRANDE · Via Prov.le M. Grande, 152 [email protected] 081 8377229 ANACAPRI · Viale De Tommaso, 8 · 081 8371015 A B C D E F G Info point CAPRI · Piazza Umberto I · 081 8370686 Deposito bagagli Marina Grande-Harbour · 081 8370634 CAPRI · Via Acquaviva ANACAPRI · Via G. Orlandi 59 · 081 8371524 MARINA GRANDE · Via C. Colombo, 10 · 081 8374575 Municipio Porte Transporte bultos a mano CAPRI · Piazza Umberto I, 9 · 081.838.6111 CO.FA.CA. · Piazza Martiri d’Ungheria · 081 8370179 Grotta Azzurra Punta ANACAPRI · Via Caprile, 30 · 081 8387111 Cooperativa Portuali Capresi del Capo Via Marina Grande, 270 · 081 8370896 Medical Assistance Punta dell’Arcera Hospital “G. Capilupi” Empresas de Navegación Piazza Marinai d’Italia Grotta ANACAPRI · Via Provinciale, 2 · 081 838 1205 Aliscafi SNAV · 081 8377577 Bagni della Ricotta CAREMAR · 081 8370700 di Tiberio Villa Lysis Monte Tiberio Emergencia sanitaria ·118 335 Guardia médica nocturna y días festivos Consorzio Linee Marittime Partenopee Villa Fersen Grotta Villa Jovis CAPRI · Piazza Umberto I, 9 · 081 8375716/8381238 081 8370819/8376995 v Palazzo del Bove Marino o i Damecuta p Chiesa a a ANACAPRI · Via Caprile, 30 · 081 8381240 -

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES in ISLAM

Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment CURRENT ISSUES IN ISLAM Editiorial Board Baderin, Mashood, SOAS, University of London Fadil, Nadia, KU Leuven Goddeeris, Idesbald, KU Leuven Hashemi, Nader, University of Denver Leman, Johan, GCIS, emeritus, KU Leuven Nicaise, Ides, KU Leuven Pang, Ching Lin, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Platti, Emilio, emeritus, KU Leuven Tayob, Abdulkader, University of Cape Town Stallaert, Christiane, University of Antwerp and KU Leuven Toğuşlu, Erkan, GCIS, KU Leuven Zemni, Sami, Universiteit Gent Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century Benjamin Nickl Leuven University Press Published with the support of the Popular Culture Association of Australia and New Zealand University of Sydney and KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). © Benjamin Nickl, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. The licence allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non- commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: B. Nickl. 2019. Turkish German Muslims and Comedy Entertainment: Settling into Mainstream Culture in the 21st Century. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Further details about Creative Commons licences -

On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word Count: 21991

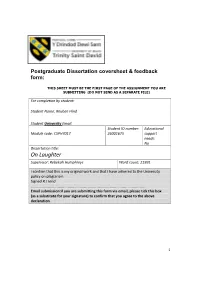

Postgraduate Dissertation coversheet & feedback form: THIS SHEET MUST BE THE FIRST PAGE OF THE ASSIGNMENT YOU ARE SUBMITTING (DO NOT SEND AS A SEPARATE FILE) For completion by student: Student Name: Reuben Hind Student University Email: Student ID number: Educational Module code: CSPH7017 26001675 support needs: No Dissertation title: On Laughter Supervisor: Rebekah Humphreys Word count: 21991 I confirm that this is my original work and that I have adhered to the University policy on plagiarism. Signed R J Hind …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Email submission:if you are submitting this form via email, please tick this box (as a substitute for your signature) to confirm that you agree to the above declaration. 1 ABSTRACT. Much of Western Philosophy has overlooked the central importance which human beings attribute to the Aesthetic experiences. The phenomena of laughter and comedy have largely been passed over as “too subjective” or highly emotive and therefore resistant to philosophical analysis, because they do not easily lend themselves to the imposition of Absolutist or strongly theory-driven perspectives. The existence of the phenomena of laughter and comedy are highly valued because they are viewed as strongly communal activities and expressions. These actually facilitate our experiences as inherently social beings, and our philosophical understanding of ourselves as beings, who experience passions and life itself amidst a world of fluctuating meanings and human drives. I will illustrate how the study of “Aesthetics” developed from Ancient Greek conceptions, through the post-Kantian and post-Romantic periods, which opened-up a pathway to the explicit consideration of the phenomena of laughter and comedy, with particular reference to the Apollonian/Dionysian conceptual schemata referred to in Nietzsche’s early works. -

In Search of Transnational Odessa (Or “Odessa the Best City in the World: All About Odessa and a Great Many Jokes”)1

FOCUS Odessity: In Search of Transnational Odessa (or “Odessa the best city in the world: All about Odessa and a great many jokes”)1 by Joachim Schlör Abstract This article presents a research into, and a very personal approach to, the “Odessa myth.” It races the emergence and development of an idea – that Odessa is different from all other cities. One main element of this mythical or legendary representation is the multi-cultural and transnational character of the city: Not only does Odessa have a Greek, an Armenian, a Jewish, a French and an Italian history, in addition to the more obvious Russian, Ukrainian, Soviet, and post-Soviet narratives, it also finds itself in more than just one place – wherever “Odessity” as a state of mind, a memory, a literary image is being celebrated and constructed. In recent years I have become more and more concerned with the notion of “Self and the City”, the idea of a personal relationship between the researcher/writer and the city he/she is looking at and walking through. So what I present here is part of an ongoing project – a building site of sorts – that connects me with the city of Odessa. One could say that I have been trying to write a book about Odessa since the end of 1993, and part of the reason for my difficulty in completing the task (or even beginning it) is the tenuous and ephemeral nature of the place itself. Where is Odessa? Or even: Does Odessa really exist? I would like to take you on a journey to and through a place of whose existence (in history and in the present) we cannot really be sure. -

Surreal Visual Humor and Poster

Fine Arts Status : Review ISSN: 1308 7290 (NWSAFA) Received: January 2016 ID: 2016.11.2.D0176 Accepted: April 2016 Doğan Arslan Istanbul Medeniyet University, [email protected], İstanbul-Turkey http://dx.doi.org/10.12739/NWSA.2016.11.2.D0176 HUMOR AND CRITICISM IN EUROPEAN ART ABSTRACT This article focused on the works of Bosh, Brughel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön and Kubin, lived during and after the Renaissance, whose works contain humor and criticism. Although these artists lived in from different cultures and societies, their common tendencies were humor and criticism in their works. Due to the conditions of the period where these artists lived in, their artistic technic and style were different from each other, which effected humor and criticism in the works too. Analyzes and comments in this article are expected to provide information regarding the humor and criticism of today’s Europe. This research will indicate solid information regarding humor and tradition of criticism in Europe through comparisons and comments on the works of the artists. It is believed that, this research is considered to be useful for academicians, students, artists and readers who interested in humour and criticism in Europe. Keywords: Humour, Criticism, Bosch, Gillray, Grandville AVRUPA SANATINDA MİZAH VE ELEŞTİRİ ÖZ Bu makale, Avrupa Rönesans sanatı dönemi ve sonrasında yaşamış Bosch, Brueghel, Archimboldo, Gillray, Grandville, Schön ve Kubin gibi önemli sanatçıların çalışmalarında görülen mizah ve eleştiri üzerine kurgulanmıştır. Bahsedilen sanatçılar farklı toplum ve kültürde yaşamış olmasına rağmen, çalışmalarında ortak eğilim mizah ve eleştiriydi. Sanatçıların bulundukları dönemin şartları gereği çalışmalarındaki farklı teknik ve stiller, doğal olarak mizah ve eleştiriyi de etkilemiştir. -

Research.Pdf (1.328Mb)

VISUAL HUMOR: FEMALE PHOTOGRAPHERS AND MODERN AMERICAN WOMANHOOD, 1860- 1915 A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Meghan McClellan Dr. Kristin Schwain, Dissertation Advisor DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright by Meghan McClellan 2017 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled Visual Humor: Female Photographers and the Making of Modern American Womanhood, 1860-1915 presented by Meghan McClellan, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Kristin Schwain Dr. James Van Dyke Dr. Michael Yonan Dr. Alex Barker To Marsha Thompson and Maddox Thornton ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The difficulty of writing a dissertation was never far from anyone’s lips in graduate school. We all talked about the blood, sweat, and tears that went into each of our projects. What we also knew was the unrelenting support our loved ones showed us day in and day out. These acknowledgments are for those who made this work possible. This dissertation is a testament to perseverance and dedication. Yet, neither of those were possible without a few truly remarkable individuals. First, thank you to all my committee members: Dr. Alex Barker, Dr. Michael Yonan, and Dr. James Van Dyke. Your input and overall conversations about my project excited and pushed me to the end. Thank you Mary Bixby for giving me the “tough love” I needed to make sure I met my deadlines. -

Das Thyssenkrupp Quartier Streifzug: Das Thyssenkrupp Quartier

Streifzug: Das ThyssenKrupp Quartier Streifzug: Das ThyssenKrupp Quartier Dauer: ca. 2 Stunden Länge: 3,6 km Ausgangspunkt: Limbecker Platz Haltestelle: Berliner Platz Limbecker Platz mit dem von Hugo Lederer Einleitung: geschaffenen Friedrich-Alfred-Krupp-Denkmal Was wäre Essen ohne Krupp? Diese Frage und dem Hotel Essener Hof um 1915 wird oft gestellt. Auf jeden Fall wäre die Ge- schichte und Entwicklung der Stadt deutlich überbaut ist, ein großes Denkmal für Fried- anders verlaufen. Kein anderes Unternehmen rich Alfred Krupp errichtet, dessen Haupt- hat in vergleichbarer Weise die Stadt Essen figur nun im Park der Villa Hügel zu finden geprägt. Lange Zeit waren Krupp und Essen ist. Vom Limbecker Platz aus führt unser Weg nahezu synonyme Begriffe. Von den bei- quer durch das Einkaufszentrum zum Berliner spiellosen betrieblichen Sozialleistungen der Platz, der erst nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg Firma Krupp zeugen heute noch viele sehens- als Teil des erweiterten Innenstadtrings ange- und vor allem bewohnenswerte Siedlungen legt wurde. Die hier beginnende Altendorfer des Werkswohnungsbaues in den Stadtteilen. Straße, ein Teil des Hellwegs, wurde Ende Der Zusammenhang zwischen Wohn- und des 18. Jahrhunderts auf Betreiben Preußens Arbeitsstätte ist hingegen kaum noch nach- ausgebaut, finanziert aus privaten Geldmitteln vollziehbar. Nur noch wenig erinnert an die der letzten Essener Fürstäbtissin Maria Kuni- gewaltige Krupp-Stadt, die vom Limbecker gunde. Der Berliner Platz wurde bis 2010 als Platz und der Bergisch-Märkischen-Bahn Kreisverkehr neu gestaltet. bis an den Rhein-Herne-Kanal reichte. Viele Jahrzehnte erstreckte sich westlich der Esse- Das frühere „Tor zur Fabrik“ (42) am Ber- ner Innenstadt eine riesige Industriebrache, liner Platz ist durch eine Eisenbahnbrücke die in weiten Teilen aus Angst vor Blindgän- der Werksbahn gekennzeichnet. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Tuesday Evening Radio Programs on Wfmt Extended Through June 2021

FROM THE CSO’S ARCHIVES: THE FIRST 130 YEARS — CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA TUESDAY EVENING RADIO PROGRAMS ON WFMT EXTENDED THROUGH JUNE 2021 CHICAGO – March 25, 2021 – The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association (CSOA) and WFMT (Chicago’s Classical Music Station) announce the extension of Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) Tuesday evening radio broadcasts From the CSO’s Archives: The First 130 Years through June 2021. Prepared with support from the Rosenthal Archives of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association, the broadcast series is part of the Orchestra’s 130th season and focuses on its extensive discography, featuring Grammy Award-winning releases, as well as recordings highlighting virtually every era in CSO history. Programs in the series are broadcast weekly on Tuesday evenings from 8:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m. (Central Time) and will be available to listeners on WFMT (98.7 FM) and streaming on wfmt.com and the WFMT app (wfmt.com/app). More information about CSOradio broadcasts, including the nationally syndicated series that airs weekly on Sundays on WFMT, is also available at cso.org/radio. Program highlights for the first six broadcasts in April and May 2021 are below. Details for the remainder of the broadcasts in this series will be posted on cso.org/radio. April 6, 2021: Benny Goodman in Nielsen and Weber In the 1960s, legendary clarinetist Benny Goodman performed with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and recorded concertos by Nielsen and Weber. This program also includes overtures by Weber and Nielsen’s Second Symphony, and a jazzy encore from Goodman, known as the “King of Swing,” performing Fred Fisher’s, “Chicago (That Toddlin’ Town).” April 13, 2021: Celebrating Victor Aitay A member of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for 50 seasons, Victor Aitay (1921-2012) attended the Franz Liszt Royal Academy in his native Hungary, where Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály and Leo Weiner were on faculty.