China on the Sea China Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern and Western Look at the History of the Silk Road

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 9, 2020 EASTERN AND WESTERN LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF THE SILK ROAD Kobzeva Olga1, Siddikov Ravshan2, Doroshenko Tatyana3, Atadjanova Sayora4, Ktaybekov Salamat5 1Professor, Doctor of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 2Docent, Candidate of historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 3Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 4Docent, Candidate of Historical Sciences, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] 5Lecturer at the History faculty, National University of Uzbekistan named after Mirzo Ulugbek, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. [email protected] Received: 17.03.2020 Revised: 02.04.2020 Accepted: 11.05.2020 Abstract This article discusses the eastern and western views of the Great Silk Road as well as the works of scientists who studied the Great Silk Road. The main direction goes to the historiography of the Great Silk Road of 19-21 centuries. Keywords: Great Silk Road, Silk, East, West, China, Historiography, Zhang Qian, Sogdians, Trade and etc. © 2020 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.09.17 INTRODUCTION another temple in Suzhou, sacrifices are offered so-called to the The historiography of the Great Silk Road has thousands of “Yellow Emperor”, who according to a legend, with the help of 12 articles, monographs, essays, and other kinds of investigations. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments

2011 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE 2011) Wuhan, China 10 - 12 May 2011 Pages 1 - 867 IEEE Catalog Number: CFP1129C-PRT ISBN: 978-1-4244-5088-6 1/7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ALGORITHMS, MODELS, SOFTWARE AND TOOLS IN BIOINFORMATICS: A Visualization Quality Evaluation Method for Multiple Sequence Alignments ............................................................1 Hongbin Lee, Bo Wang, Xiaoming Wu, Yonggang Liu, Wei Gao, Huili Li, Xu Wang, Feng He A New Promoter Recognition Method Based On Features Optimal Selection.................................................................5 Lan Tao, Huakui Chen, Yanmeng Xu, Zexuan Zhu A Center Closeness Algorithm For The Analyses Of Gene Expression Data ...................................................................9 Huakun Wang, Lixin Feng, Zhou Ying, Zhang Xu, Zhenzhen Wang A Novel Method For Lysine Acetylation Sites Prediction ................................................................................................ 11 Yongchun Gao, Wei Chen Weighted Maximum Margin Criterion Method: Application To Proteomic Peptide Profile ....................................... 15 Xiao Li Yang, Qiong He, Si Ya Yang, Li Liu Ectopic Expression Of Tim-3 Induces Tumor-Specific Antitumor Immunity................................................................ 19 Osama A. O. Elhag, Xiaojing Hu, Weiying Zhang, Li Xiong, Yongze Yuan, Lingfeng Deng, Deli Liu, Yingle Liu, Hui Geng Small-World Network Properties Of Protein Complexes: Node Centrality And Community Structure -

An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2006 Innovation through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China Benjamin L. Liebman Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin L. Liebman, Innovation through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China, 47 HARV. INT'L L. J. 33 (2006). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/554 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 47, NUMBER 1, WINTER 2006 Innovation Through Intimidation: An Empirical Account of Defamation Litigation in China Benjamin L. Liebman* INTRODUCTION Consider two recent defamation cases in Chinese courts. In 2004, Zhang Xide, a former county-level Communist Party boss, sued the authors of a best selling book, An Investigation into China's Peasants. The book exposed official malfeasance on Zhang's watch and the resultant peasant hardships. Zhang demanded an apology from the book's authors and publisher, excision of the offending chapter, 200,000 yuan (approximately U.S.$25,000)' for emotional damages, and a share of profits from sales of the book. Zhang sued 2 in a local court on which, not coincidentally, his son sat as a judge. * Associate Professor of Law and Director, Center for Chinese Legal Studies, Columbia Law School. -

Medical History Hare-Lip Surgery in the History Of

Medical History http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH Additional services for Medical History: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine Kan-Wen Ma Medical History / Volume 44 / Issue 04 / October 2000, pp 489 - 512 DOI: 10.1017/S0025727300067090, Published online: 16 November 2012 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0025727300067090 How to cite this article: Kan-Wen Ma (2000). Hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine. Medical History, 44, pp 489-512 doi:10.1017/S0025727300067090 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/MDH, IP address: 144.82.107.82 on 08 Nov 2013 Medical History, 2000, 44: 489-512 Hare-Lip Surgery in the History of Traditional Chinese Medicine KAN-WEN MA* There have been a few articles published in Chinese and English on hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine. They are brief and some of them are inaccurate, although two recent English articles on this subject have presented an adequate picture on some aspects.' This article offers unreported information and evidence of both congenital and traumatic hare-lip surgery in the history of traditional Chinese medicine and also clarifies and corrects some of the facts and mistakes that have appeared in works previously published either in Chinese or English. Descriptions of Hare-Lip and its Treatment in Non-Medical Literature The earliest record of hare-lip in ancient China with an imaginary explanation for its cause is found in jtk Huainan Zi, a book attributed to Liu An (179-122 BC). -

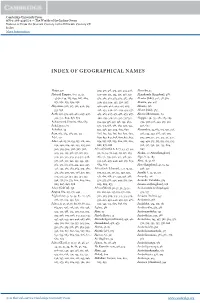

Index of Geographical Names

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42465-3 — The Worlds of the Indian Ocean Volume 2: From the Seventh Century to the Fifteenth Century CE Index More Information INDEX OF GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES Abaya, 571 309, 317, 318, 319, 320, 323, 328, Akumbu, 54 Abbasid Empire, 6–7, 12, 17, 329–370, 371, 374, 375, 376, 377, Alamkonda (kingdom), 488 45–70, 149, 185, 639, 667, 669, 379, 380, 382, 383, 384, 385, 389, Alaotra (lake), 401, 411, 582 671, 672, 673, 674, 676 390, 393, 394, 395, 396, 397, Alasora, 414, 427 Abyssinia, 306, 317, 322, 490, 519, 400, 401, 402, 409, 415, 425, Albania, 516 533, 656 426, 434, 440, 441, 449, 454, 457, Albert (lake), 365 Aceh, 198, 374, 425, 460, 497, 498, 463, 465, 467, 471, 478, 479, 487, Alborz Mountains, 69 503, 574, 609, 678, 679 490, 493, 519, 521, 534, 535–552, Aleppo, 149, 175, 281, 285, 293, Achaemenid Empire, 660, 665 554, 555, 556, 557, 558, 559, 569, 294, 307, 326, 443, 519, 522, Achalapura, 80 570, 575, 586, 588, 589, 590, 591, 528, 607 Achsiket, 49 592, 596, 597, 599, 603, 607, Alexandria, 53, 162, 175, 197, 208, Acre, 163, 284, 285, 311, 312 608, 611, 612, 615, 617, 620, 629, 216, 234, 247, 286, 298, 301, Adal, 451 630, 637, 647, 648, 649, 652, 653, 307, 309, 311, 312, 313, 315, 322, Aden, 46, 65, 70, 133, 157, 216, 220, 654, 657, 658, 659, 660, 661, 662, 443, 450, 515, 517, 519, 523, 525, 230, 240, 284, 291, 293, 295, 301, 668, 678, 688 526, 527, 530, 532, 533, 604, 302, 303, 304, 306, 307, 308, Africa (North), 6, 8, 17, 43, 47, 49, 607 309, 313, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 50, 52, 54, 70, 149, 151, 158, -

What Are Reflected by the Navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus

International Relations and Diplomacy, February 2018, Vol. 6, No. 02, 110-121 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2018.02.005 D D AV I D PUBLISHING What are Reflected by the Navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus WANG Min-qin Hunan University, Changsha, China The contrast of the navigations of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus shows two kinds of humanistic values: harmonious altruism reflected by Chinese culture and aggressive egocentrism revealed by the Western culture and their different effects on the world. This article explores the reasons for their different actions, trying to demonstrate that Western humanistic education is problematic. Keywords: Western culture, Chinese culture, humanism, values Introduction There were a lot of articles and books discussing about Zheng He and Christopher Columbus separately. Columbus’s studies paid more attention to Columbus’s voyages and their impact to local people. The Tainos: Rise & Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus edited by Irving Rouse (1992) was a temperate and balanced description. Samuel M. Wilson (1990) illustrated the character and destruction of Taino culture in Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. The effect of the first encounters on the native populations was given by James Axtell (1992) in Beyond 1492: Encounters in Colonial North America. The debate over Columbus’s achievements was presented in Secret Judgments of God: Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America edited by Noble David Cook and W. George Lovell (1991) on the disastrous effects on the native peoples. An anti-European treatment was shown in Ray González’s (1992) Without Discovery: A Native Response to Columbus (Flint, 2014). -

Zheng He and the Confucius Institute

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 3-2018 The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute Peter Weisser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Weisser, Peter, "The Admiral's Carrot and Stick: Zheng He and the Confucius Institute" (2018). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 625. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/625 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Science by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 THE ADMIRAL’S CARROT AND STICK: ZHENG HE AND THE CONFUCIUS INSTITIUTE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Peter Eli Weisser March 2018 Approved by: Jeremy Murray, Committee Chair, History Jose Munoz, Committee Member ©2018 Peter Eli Weisser ABSTRACT As the People’s Republic of China begins to accumulate influence on the international stage through strategic usage of soft power, the history and application of soft power throughout the history of China will be important to future scholars of the politics of Beijing. -

Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Yuanfei Wang University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Wang, Yuanfei, "Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 938. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/938 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genre and Empire: Historical Romance and Sixteenth-Century Chinese Cultural Fantasies Abstract Chinese historical romance blossomed and matured in the sixteenth century when the Ming empire was increasingly vulnerable at its borders and its people increasingly curious about exotic cultures. The project analyzes three types of historical romances, i.e., military romances Romance of Northern Song and Romance of the Yang Family Generals on northern Song's campaigns with the Khitans, magic-travel romance Journey to the West about Tang monk Xuanzang's pilgrimage to India, and a hybrid romance Eunuch Sanbao's Voyages on the Indian Ocean relating to Zheng He's maritime journeys and Japanese piracy. The project focuses on the trope of exogamous desire of foreign princesses and undomestic women to marry Chinese and social elite men, and the trope of cannibalism to discuss how the expansionist and fluid imagined community created by the fiction shared between the narrator and the reader convey sentiments of proto-nationalism, imperialism, and pleasure. -

UNDERSTANDING CHINA a Diplomatic and Cultural Monograph of Fairleigh Dickinson University

UNDERSTANDING CHINA a Diplomatic and Cultural Monograph of Fairleigh Dickinson University by Amanuel Ajawin Ahmed Al-Muharraqi Talah Hamad Alyaqoobi Hamad Alzaabi Molor-Erdene Amarsanaa Baya Bensmail Lorena Gimenez Zina Ibrahem Haig Kuplian Jose Mendoza-Nasser Abdelghani Merabet Alice Mungwa Seddiq Rasuli Fabrizio Trezza Editor Ahmad Kamal Published by: Fairleigh Dickinson University 1000 River Road Teaneck, NJ 07666 USA April 2011 ISBN: 978-1-457-6945-7 The opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors alone, and should not be taken as necessarily reflecting the views of Fairleigh Dickinson University, or of any other institution or entity. © All rights reserved by the authors No part of the material in this book may be reproduced without due attribution to its specific author. THE AUTHORS Amanuel Ajawin is a diplomat from Sudan Ahmed Al-Muharraqi is a graduate student from Bahrain Talah Hamad Alyaqoobi is a diplomat from Oman Hamad Alzaabi a diplomat from the UAE Molor Amarsanaa is a graduate student from Mongolia Baya Bensmail is a graduate student from Algeria Lorena Gimenez is a diplomat from Venezuela Zina Ibrahem is a graduate student from Iraq Ahmad Kamal is a Senior Fellow at the United Nations Haig Kuplian is a graduate student from the United States Jose Mendoza-Nasser is a graduate student from Honduras Abdelghani Merabet is a graduate student from Algeria Alice Mungwa is a graduate student from Cameroon Seddiq Rasuli is a graduate student from Afghanistan Fabrizio Trezza is a graduate student from Italy INDEX OF -

The Chinese Deployment to the Gulf of Aden Is Historic and Significant

Copyright © 2009, Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland (410) 268-6110 www.usni.org By Andrew S. Erickson, Naval War College; and Lieutenant Justin D. Mikolay, U.S. Navy The Chinese deployment to the Gulf of Aden is historic and significant. 34 • March 2009 www.usni.org he ongoing deployment of Chinese their vulnerable ships through the Gulf of naval vessels to the troubled Gulf of Aden.2 China has already escorted a wide va- Aden signals an important step in the riety of Chinese and even some foreign ships evolution of the People’s Liberation in an area west of longitude 57 degrees east TArmy Navy (PLAN). Observers of China’s and south of latitude15 degrees north.3 growing naval fleet have long imagined sce- The United States, in accordance with its new maritime strategy, has wel- comed China’s participation as an example of cooperation that furthers international security. On 18 December at the Foreign Press Center in Washington, D.C., Admiral Timothy Keating, Com- mander, U.S. Pacific Command, vowed to “work closely” with the Chinese flotilla, and use the event as a potential “springboard for the resumption of dialog be- tween People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces and the U.S. Pacific Command forces.”4 While the Chinese motivation to deploy to the Gulf of Aden clearly springs from a variety of factors, Beijing’s contribu- tion to maritime security should indeed be applauded. “This au- gurs well for increased coopera- tion and collaboration between the Chinese military forces and narios that might prompt the PLAN to exer- U.S. -

Yo Ho Ho and a Bucket of Cash the Need to Enchance Regional Effort to Combat Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships in Southeast Asia

Towards principled ›sheries governance australian and indonesian : approaches and challenges... YO HO HO AND A BUCKET OF CASH THE NEED TO ENCHANCE REGIONAL EFFORT TO COMBAT PIRACY AND ARMED ROBBERY AGAINST SHIPS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Hersapta Mulyono* Abstract The problem of piracy is that the world press nowadays often focuses on waters off the coast of Somalia and the Gulf of Aden. That is understandable given the recent phenomenal upsurge of piratical activities in that poverty stricken part of the world. Poverty, alongwith degradation of the rule of law, is often a catalyst for criminal acts, and if that situation occurred in maritime neighborhood, it usually takes form of piracy and armed robbery against ships. Southeast Asia is one of those places. The primary purpose of this essay is to examine the de›ciencies of regional efforts to combat piracy and armed robbery against ships in Southeast Asia. To provide readers with an understanding of the legal dif›culties involved with piracy and armed robbery in Southeast Asia Keywords: Piracy, armed robbery against ships, regional cooperation I. INTRODUCTION ...Soon after the pirates had boarded the tanker ... Bedlam erupted on the ship’s decks as the pirates tried to round up the frightened crew... [The pirates] were on the bridge. They switched on the public address system and started beating the captain until his shouts for the crew to surrender blared over the ship’s loudspeakers. ‘Please, they are killing me,’ he cried. Sixteen crewmen eventually gave up. Each was asked his name, then bound and blindfolded.1 * The author obtained his LL.B.