CICERO COR/Applicationfiles/9781844658404 Text.3D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

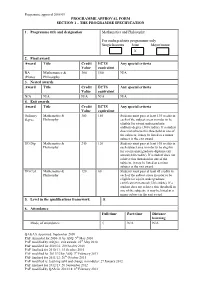

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

Classical Philosophy

Classical Philosophy “This is a fine introduction to ancient philosophy, consistently clear and carefully argued; interesting and generally attractive to read. I also enjoyed how the various views of the philosophers were successfully tied to overarching themes, such as the contrast between the manifest and the scientific image of the world.” Vasilis Politis, Trinity College, Dublin “I found the volume well organized and philosophically engaging. It doesn’t talk down to the reader, nor attempt to blind him/her with science (or philosophy), so it should be well suited for the intelligent non-expert.” Raphael Woolf, Harvard University The origins of Western philosophy can be found in sixth-century BC Greece. There it was that philosophy developed into a discipline that considered such fundamental questions as the nature of human existence, our place in the universe, and our attitudes towards an interactive politicized society. Every development in philosophy indeed stems from the thinkers of this enlightened time. Classical Philosophy is a comprehensive examination of early philosophy, from the Presocratics through to Aristotle. The aim of the book is to provide an explanation and analysis of the ideas that flourished at this time, and to consider their relevance, both to the historical development of philosophy and to contemporary philosophy today. From these ideas we can see the roots of arguments in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and political philosophy. The book is arranged in four parts by thinker and covers • the Presocratics • Socrates • Plato • Aristotle Christopher Shields’ style is inviting, refreshing, and ideal for anyone coming to the subject for the first time. -

Department Newsletter, 2018

Yale Department of Classics Summer 2018 Greetings from the Chair: As you’ll see on pp. 10-11, same time, we expect students to acquire familiarity with at a conservative estimate the history of classical scholarship and protean receptions this past year the Classics of classical antiquity. All the while, in the tradition of the department organized liberal arts, students bring the insights of many disciplines or co-sponsored a and different theoretical frames to their work and subject staggering sixty-four the study of antiquity to “wake work,” in Christina Sharpe’s events, prompting us to formulation, troubling our relationship with the past. In realize that there is an short, we try to train our students to be cosmonauts of upper limit to the number ancient Mediterranean civilizations and their afterlives: of lectures, seminars, and capable of interpreting both antiquity’s realia and its other events compatible fantasies and of analyzing modern fantasies about antiquity. with a good life. The last This May we graduated ten majors, five of whom were event of the year was decidedly glukupikros (sweetbitter), double majors and all of whom demonstrated this impressive as we celebrated Professor Victor Bers’s career at Yale, spanning range in their work. We congratulate Giorgio Caturegli, forty-six years: sweet as we celebrated Victor’s scholarly Luke Chang, Nicholas Dell Isola, Paul Eberwine, Sherry achievements and his extraordinarily generous mentorship Lee, Courtney Screen, Deniz Tanyolac, Victor Wang, Eli of generations of scholars, bitter as we contemplated his Westerman, and Nina Zoubek. With fourteen rising seniors, retirement. You can read more about this event on p. -

Academic Eloquence and the End of Cicero's De Finibus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository ACADEMIC ELOQUENCE AND THE END OF CICERO’S DE FINIBUS * A.G.Long Abstract The paper considers why the structure of Cicero’s De Finibus implicitly favours the Academy, even though Cicero avoids a decision between the Stoic theory and Antiochus’ theory. Cicero’s educational aims require him to illustrate not only a range of theories but a range of criteria by which theories and the exposition of theories should be judged. By one criterion – style of exposition – the entire Academic tradition, not Antiochus specifically, is endorsed. Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum stages debates between exponents and critics of three ethical theories, with the part of critic taken by Cicero himself in each of the three debates. The first theory is Epicurean, the second Stoic; the third is harder to label, as it is attributed by Cicero not to a single philosopher or school but to a trio: Antiochus, Peripatetics and the so-called ‘Old Academy’ (v 8; cf. ii 34 and v 21). Like others I shall refer to it as the ‘Antiochian’ theory, but it is important to keep in mind Cicero’s claim (which evidently derives from Antiochus himself, v 14) that the theory’s provenance is pre-Antiochian too. In the survey of his philosophical writing in De Divinatione Cicero says that his aim in writing De Finibus was to make known the arguments for and against each of the philosophers’ theories (ii 2). -

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department Of

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department of Philosophy Princeton University Phone: (609) 258 4300 Email: [email protected] Academic Employment Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2012 – present Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2007 – 2012 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2001 – 2007 Lecturer in Philosophy, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 2000 – 2001 Junior Research Fellow, St John’s College, Oxford, 1999 – 2001 Lecturer in Philosophy, New College, Oxford, 1998 – 1999 Education D. Phil., Philosophy, University of Oxford, October 2000 M. Phil., Ancient Philosophy, University of Cambridge, September 1996 B. A., Classics, University of Cambridge, September 1995 Area of Specialization Ancient Philosophy Honors and Awards Behrman Fellow in the Humanities, Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, 2007–2009 Robert K. Root University Preceptorship, Princeton University, 2005–2008 Publications “Aristotle’s Empiricist Theory of Doxastic Knowledge,” with Benjamin Morison (under review) 1 “Intelligence as Cause: P hilebus 2 7c31b,” P lato Dialogue Project: Plato’s P hilebus, ed. by Panos Dimas, Gabriel Lear, and Russell Jones (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) “The Principles of Natural Things: Two or Three? Aristotle, P hysics I 7, 190b17191a22,” Symposium Aristotelicum on P hysics Book I, ed. by Katerina Ierodiakonou and Paul Kalligas (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) Review of Christopher Shields, Aristotle : De Anima, T ranslation, Introduction and Commentary, in N otre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 2 017 “Natural Goals of Actions in Aristotle,” J ournal of the American Philosophical Association, Volume 1, Issue 4, Winter 2015, 583–600 “Aristotle’s analysis of akratic action,” in R. Polansky (ed.), T he Cambridge Companion to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 2014), 242–262 “Understanding, knowledge, and inquiry in Aristotle,” in F. -

The Birth of Belief, (PDF)

The Birth of Belief Jessica Moss (NYU) and Whitney Schwab (UMBC)* Forthcoming in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 1 Introduction Did Plato and Aristotle have anything to say about belief? The answer to this question might seem blindingly obvious: of course they did. Plato distinguishes belief from knowledge in the Meno, Republic, and Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the Posterior Analytics. Plato distinguishes belief from perception in the Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the de Anima. They talk about the distinction between true and false beliefs, and the ways in which belief can mislead and the ways in which it can steer us aright. Indeed, they make belief a central component of their epistemologies. The view underlying these claims—one so widespread these days as to remain largely unquestioned—is that when Plato and Aristotle talk about doxa, they are talking about what we now call belief. Or, at least, they are talking about something so closely related to what we now call belief that no philosophical importance can be placed on any differences. Doxa is the ancient counterpart of belief: hence, the use nowadays of ‘doxastic' as the adjective corresponding to ‘belief.' One of our aims in this paper is to challenge this view. We argue that Plato and Aristotle raise questions and advance views about doxa that would be very strange if they concerned belief. This suggests either that Plato and Aristotle had very strange ideas about belief, or that doxa is not best understood as belief. We argue for the latter option by pursuing our second aim, which is to show that Aristotle, expanding on ideas suggested in Plato, explicitly develops a notion that corresponds much more closely to our modern notion of belief: hupolepsis. -

1 / Swanson RESEARCH AREAS

Curriculum Vitae CARRIE E. SWANSON Assistant Professor Department of Philosophy | University of Iowa Room 256 | English-Philosophy Building Iowa City, IA 52240 Email: [email protected] Phone: (319)-335-5313 (work) (609) 865-8012 (home) EDUCATION: Reed College (B.A. Philosophy, 1991). Thesis: Plato’s Philebus. Supervisor: C.D.C. Reeve. Rutgers University, New Brunswick 2003-2011. Ph.D. Philosophy, May 2011. Dissertation: Socratic Dialectic and the Resolution of Fallacy in Plato’s Euthydemus. Committee: Alan Code, Robert Bolton, Jeff King (Rutgers), Benjamin Morison (Princeton). PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: 2013 to present: Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Iowa. 2011-2013: Ruth Norman Halls Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy, Indiana University. HONORS AND AWARDS: Rutgers Graduate School-New Brunswick Dissertation Teaching Award 2009-2010. Rutgers University Sellon Dissertation Fellowship 2008-2009. ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS: Chicago Area Consortium in Ancient Philosophy (2013-present). International Plato Society (2011-present). Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy (2010-present). American Philosophical Association (2008-present). Princeton University Reading Group in Ancient Philosophy (2001-2010). (Presented multiple times on the following Greek texts: Aristotle: Metaphysics Beta; Nicomachean Ethics 7; De Anima 1-2; De Motu Animalium. Plato: Theaetetus; Republic 6-7; Sophist; Timaeus. Sextus: Outlines III (on the good, bad, and indifferent, and the art of living); Epicurus: Letter to Herodotus. Regular faculty participants: John Cooper, Christian Wildberg, Hendrik Lorenz, Ben Morison, Alexander Nehamas. Past visiting participants: Michael Frede, Myles Burnyeat, Stephen Menn, Thomas Johansen, Raphael Woolf, Ursula Coope, Jonathan Beere). 1 / Swanson RESEARCH AREAS: Area of specialization: Ancient Philosophy. -

THE VASSAR COLLEGE JOURNAL of PHLOSOPHY Issue 4 Spring 2017

i THE VASSAR COLLEGE JOURNAL OF PHLOSOPHY Issue 4 Spring 2017 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Sam Allen • Asprey Liu EDITORIAL BOARD Steven Docto Annabelle Hall Mateusz Kasprowicz Sophie Kosmacher Henry Krusoe Josephine Lovejoy Ben Luongo Michaela Murphy Hui Xin Ng Doga Oner Griffin Pion Marco Pittarelli Gordon Schmidt FACULTY ADVISOR Giovanna Borradori Authorization is granted to photocopy for personal or internal use or for free distribution. Inquiries regarding reproduction and subscription should be addressed to Vassar College Journal of Philosophy at [email protected]. ii iii iv CONTENTS Acknowledgments .............................................................................................. iv Letter from the Editors-In-Chief ....................................................................... v Epicurus: A Psychological Hedonist ........................................................... 6 Paul Karcis Concordia University Decaffeination and Meta-Choice: ........................................................ 19 Freedom and Action within the Terrorism/Anti-Terrorism Discourse Daniel Godstone University of Melbourne Yes Loitering: Destituting Surveillance in the Post-Orwellian Era.... 31 Asprey Liu Vassar College A Review of Martha C. Nussbaum, Anger and Forgiveness: ............. 40 Resentment, Generosity, Justice Josephine Lovejoy Vassar College Narratively Inclined: Ontologies of Self, Sexuality, and Violence. .... 46 An Interview with Adriana Cavarero Asprey Liu, Sam Allen, and Giovanna Borradori Vassar College Call for -

Is Aristotle a Virtue Ethicist? in V

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1017/9781108163866 10.1017/9781108163866.013 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Aufderheide, J. (2017). Is Aristotle a Virtue Ethicist? In V. Harte, & R. Woolf (Eds.), Rereading Ancient Philosophy: Old Chestnuts and Sacred Cows (pp. 199-220). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108163866, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108163866.013 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Ancient Philosophy of the Self the New Synthese Historical Library Texts and Studies in the History of Philosophy

Ancient Philosophy of the Self The New Synthese Historical Library Texts and Studies in the History of Philosophy VOLUME 64 Managing Editor: SIMO KNUUTTILA, University of Helsinki Associate Editors: DANIEL ELLIOT GARBER, Princeton University RICHARD SORABJI, University of London Editorial Consultants: JAN A. AERTSEN, Thomas-Institut, Universität zu Köln ROGER ARIEW, University of South Florida E. JENNIFER ASHWORTH, University of Waterloo MICHAEL AYERS, Wadham College, Oxford GAIL FINE, Cornell University R. J. HANKINSON, University of Texas JAAKKO HINTIKKA, Boston University PAUL HOFFMAN, University of California, Riverside DAVID KONSTAN, Brown University RICHARD H. KRAUT, Northwestern University, Evanston ALAIN DE LIBERA, Université de Genève JOHN E. MURDOCH, Harvard University DAVID FATE NORTON, McGill University LUCA OBERTELLO, Università degli Studi di genova ELEONORE STUMP, St. Louis University ALLEN WOOD, Stanford University For other titles published in this series, go to www.springer.com/series/6608 Pauliina Remes • Juha Sihvola Editors Ancient Philosophy of the Self Editors Pauliina Remes Juha Sihvola Uppsala University Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies Sweden University of Helsinki and Finland University of Helsinki Finland ISBN 978-1-4020-8595-6 e-ISBN 978-1-4020-8596-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008928521 © 2008 Springer Science + Business Media B.V. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. -

INTRODUCTION Anne Sheppard

INTRODUCTION Anne Sheppard Shortly before his retirement as Publications Manager for the Institute of Classical Studies, Richard Simpson suggested to me that I might select about a dozen articles on ancient philosophy from the Institute’s Bulletin for publication together as a virtual issue. I consulted other ancient philosophy colleagues in the University of London and, following helpful advice from Joachim Aufderheide and Raphael Woolf, agreed to select from issues of BICS from 1980 to the present. A good deal of the material on ancient philosophy published by BICS since 1980 has appeared in supplementary volumes, which either collected papers from a particular seminar series at the Institute or published the proceedings of conferences held under its auspices.1 The proceedings of two further conferences, one in honour of Bill Fortenbaugh, the other in honour of Bob Sharples, have been published together as either part or all of a regular volume of BICS.2 In selecting papers for inclusion in this virtual issue, I have ignored these existing collections and considered only papers published in ‘general’ volumes of BICS containing a range of material drawn from the whole spectrum of classical studies. Making such a selection means making choices, some of them difficult. I excluded a number of papers which I judged to have been superseded by subsequent publications by their authors as well as some which were more concerned with the historical context of ancient philosophy than with philosophy itself and others which arguably belonged more to the history of science than to philosophy. Out of those which remained when I had applied these principles of selection, I have chosen for re-publication a total of 12 papers which I 1 Between 1997 and 2014 eleven BICS supplements were published on ancient philosophy broadly construed, many of them focusing on post-Aristotelian philosophy.