Belief and Persuasion in the Socratic Elenchus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socratic Dialogue: Teaching Patients to Become Their Own Cognitive Therapist

National Crime Victims Center > Socratic Method > Socratic Dialogue Print This Page Socratic Dialogue: Teaching Patients to Become Their Own Cognitive Therapist “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates (469 BC – 399 BC) Socratic dialogue is a foundational skill used by CPT therapists to help patients examine their lives, challenge maladaptive thoughts, address stuckpoints, and develop critical thinking skills. Socratic dialogue is derived from the work of the Greek philosopher, Socrates, who developed what is now called the Socratic method of teaching. In traditional education, the teacher is presumed to know more than the student, and the role of the teacher is to transmit the teacher’s knowledge to the student. In contrast, Socrates believed that the role of the teacher should not be to tell students what the “truth” is but to help them discover the truth themselves through a collaborative process of asking questions. By asking a series of questions designed to get the student to identify logical contradictions in their positions and/or evidence that does not support their thoughts, the Socratic method is designed to help the student discover the “truth” for themselves as opposed to being told what the “truth” is by the teacher. Socrates also thought this teaching method was superior because it teaches students the skill of critical thinking, a skill they can use throughout their lives. Another advantage of this method is that students are more likely to value knowledge if they discover it themselves than if someone tells them about it. In CPT, the purpose of Socratic questioning by the therapist is to prompt the patient to examine the accuracy of maladaptive thoughts that are causing psychological distress. -

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

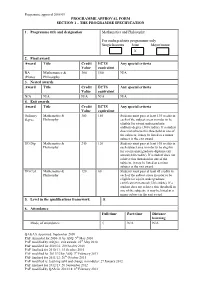

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

Induction in the Socratic Tradition John P

Induction in the Socratic Tradition John P. McCaskey Stanford University Abstract: Aristotle said that induction (epagǀgƝ) is a proceeding from particulars to a universal, and the definition has been conventional ever since. But there is an ambiguity here. Induction in the Scholastic and the (so-called) Humean tradition has presumed that Aristotle meant going from particular statements to universal statements. But the alternate view, namely that Aristotle meant going from particular things to universal ideas, prevailed all through antiquity and then again from the time of Francis Bacon until the mid-nineteenth century. Recent scholarship is so steeped in the first-mentioned tradition that we have virtually forgotten the other. In this essay McCaskey seeks to recover that alternate tradition, a tradition whose leading theoreticians were William Whewell, Francis Bacon, Socrates, and in fact Aristotle himself. The examination is both historical and philosophical. The first part of the essay fills out the history. The latter part examines the most mature of the philosophies in the Socratic tradition, specifically Bacon’s and Whewell’s. After tracing out this tradition, McCaskey shows how this alternate view of induction is indeed employed in science, as exemplified by several instances taken from actual scientific practice. In this manner, McCaskey proposes to us that the Humean problem of induction is merely an artifact of a bad conception of induction and that a return to the Socratic conception might be warranted. Introduction Aristotle said that induction (epagǀgƝ) is a proceeding from particulars to a universal, and the definition has been conventional ever since. But there is an ambiguity here. -

Applying the Socratic Method to the Problem Solving Process

American Journal of Business Education – August 2009 Volume 2, Number 5 Socratic Problem-Solving In The Business World Evan Peterson, University Of Detroit Mercy, USA ABSTRACT Accurate and effective decision-making is one of the most essential skills necessary for organizational success. The problem-solving process provides a systematic means of effectively recognizing, analyzing, and solving a dilemma. The key element in this process is critical analysis of the situation, which can be executed by a taking a Socratic approach to the situation. Applying the Socratic Method to the problem-solving model ensures a well-rounded and versatile analysis. Keywords: Problem-solving process, decision- making, critical analysis, Socratic Method INTRODUCTION he sheer complexity of today’s business organization is rivaled only by the complexity of the business environment in which it operates. The permutation of complexity and exacting time constraints companies and individuals face in making vital decisions involving thousands of people Tand millions of dollars can seem more daunting than storming the beaches of Normandy. However, all hope is not lost. The anxiety, along with the blood, sweat, and tears that come along with difficult decision-making can be reduced by having a clear, time-tested plan of attack that can be applied to the problem situation. The problem-solving model is one such plan of attack, for it provides a framework that an individual decision-maker or group of decision-makers can follow to reach a feasible solution to the problem. Situational analysis is the bread and butter of the problem-solving model, for it goes hand-in-hand with each step of the model. -

THE SOCRATIC METHOD AS an APPROACH in TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES: a LITERATURE REVIEW Mary Grace Ann S

GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 12, December 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 770 GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 12, December 2020, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com THE SOCRATIC METHOD AS AN APPROACH IN TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES: A LITERATURE REVIEW Mary Grace Ann S. Maigue Senior High School Teacher, Our Lady of Peace School Antipolo City, Rizal, Philippines [email protected] ABSTRACT Enhancing the critical thinking skills of students is one of the principal goals of many educational institutions. This paper presents various articles discussing the general features of the Socratic Method in improving the critical thinking skills of students. Specifically, this study focuses on the importance of incorporating Socratic questioning in teaching Social Studies. The primary resources of this paper were taken from international journals. Related studies reveal that when teachers use Socratic questioning, students examine and probe their thoughts by making them explicit thus allowing them to develop and evaluate their thinking while overtly expressing their ideas. This in turn, is the paramount objective targeted by the Socratic Method, a student with an enriched critical mind. Keywords: Critical Thinking, Socratic Method of Teaching, Social Studies GSJ© 2020 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: Volume 8, Issue 12, December 2020 ISSN 2320-9186 771 INTRODUCTION Critical thinking as the primary cognitive skill is one of the targeted areas that education is prompted to nourish. With this skill, we are able to process information given to us with the aid of our senses and to think profoundly such information. Poor critical thinking necessitates risks such as weak decision-making, repeated mistakes, inappropriate assumptions, etc. -

The Stoics and the Practical: a Roman Reply to Aristotle

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2013 The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle Robin Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Robin, "The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle" (2013). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 143. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STOICS AND THE PRACTICAL: A ROMAN REPLY TO ARISTOTLE A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 BY Robin Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL - TABLE OF CONTENTS - Introduction……………………..............................................................................................................p.i Chapter One: Practical Knowledge and its Others Technê and Natural Philosophy…………………………….....……..……………………………….....p. 1 Virtue and technical expertise conflated – subsequently distinguished in Plato – ethical knowledge contrasted with that of nature in -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

Socratic Method’ in the Developmental Stages of Philosophy

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 Received: 23-10-2020; Accepted: 08-11-2020; Published: 25-11-2020 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 6; Issue 6; 2020; Page No. 72-75 The role of the ‘Socratic method’ in the developmental stages of philosophy Pulenthiran Nesan M. Phil Student, Post graduate Institute of Humanities and Social sciences, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka Abstract This study aims to uncover man-centered ideas by Socrates through his method (Socratic) in the course of his inquiry, free from the research of the philosophy of nature. The problem with this study is how Socrates was able to make a proper investigate into man and his life, despite the influence of his earlier thinking. What is the meaning of life? Hypotheses such as the practical application of discipline in life are put forward. Information related to this subject is derived from reports, texts, etc. of a previous study, and the study uses descriptive analysis. Greek philosophy, delighted with Ionian thought, led to the next stage of development as the Sophist thinking. It was these Sophists who first proposed the concept of man. Socrates' philosophy, which developed after them, further clarified the study of man and established a new system of philosophy. His method of dialogue, which transcends precedents, revealed the solid foundations of man, and his method was passed on to the next generation by the direct student Plato and others, such as Aristotle. It also had great influence on philosophy. -

The Socratic Method in the Age of Trauma

THE SOCRATIC METHOD IN THE AGE OF TRAUMA Jeannie Suk Gersen When I was a young girl, the careers I dreamed of — as a prima ballerina or piano virtuoso — involved performing before an audience. But even in my childhood ambitions of life on stage, no desire of mine involved speaking. My Korean immigrant family prized reading and the arts, but not oral expression or verbal assertiveness — perhaps even less so for girls. Education was the highest familial value, but a posture of learning anything worthwhile seemed to go together with not speak- ing. My incipient tendency to raise questions and arguments was treated as disrespect or hubris, to be stamped out, sometimes through punish- ment. As a result, and surely also due to natural shyness, I had an almost mute relation to the world. It was 1L year at Harvard Law School that changed my default mode from “silent” to “speak.” Having always been a student who said nothing and preferred a library to a classroom, I was terrified and scandalized as professors called on classmates daily to engage in back-and-forth dia- logues of reasons and arguments in response to questions, on subjects of which we knew little and on which we had no business expounding. What happened as I repeatedly faced my unwelcome turn, heard my voice, and got through with many stumbles was a revelation that changed my life. A light switched on. Soon, I was even volunteering to engage in this dialogue, and I was thinking more intensely, independently, and enjoyably than I ever had before. -

The Socratic Handbook: the Enchiridion As a Guide for Emulating Socrates1

The Socratic Handbook: The Enchiridion as a Guide for Emulating Socrates1 Chad E. Brack February 8, 2020 Abstract: In this paper, I argue that the works of Epictetus are best understood as a guide for living like Socrates. On my view, we can think of the Enchiridion as a Socratic handbook, meaning it is less about the philosophy of Epictetus himself than it is about Epictetus’s prescription for achieving a Socratic disposition. In other words, Epictetus tells us how to live our lives as Socrates did. He believes doing so will lead us to the Good Life and the tranquility that accompanies it. I begin by discussing Socratic ethics and Socrates’s influence on Stoicism, then I suggest that the content and structure of Epictetus’s work points to Socrates as the prime focus for Epictetus’s teachings. Socrates is not just an example of sagacity—he is the subject of study. After offering the reasoning for my view, I address what I believe to be the most likely objections to my interpretation and conclude with final thoughts about Stoicism as a Socratic philosophy of life. I. Introduction In recent years Stoicism has reemerged as an attractive philosophy of life. It has also become a tool for self-help and cognitive behavioral therapy. Founded over 2000 years ago, Stoicism has touched the lives of countless people. The Stoics taught a philosophy based on building the right mental state to deal with life’s challenges and to achieve contentment regardless of circumstances. It is a philosophy based on well-being. -

Socratic Method ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ Σωκράτης

The Socratic Method ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ Σωκράτης Callie Dawson and Hans Corbell Socrates & the Socratic Method ● Socrates was a classical Greek philosopher who is credited with laying the fundamentals of modern Western philosophy. ● He is known for creating Socratic irony and the Socratic method, and also for his profound influence on Western philosophy, along with his students Plato and Aristotle. ● Socrates taught his students by presenting multiple questions in effort to partake in critical thinking, reasoning, and logic. ● In a typical Socratic dialogue, Socrates will ask a person to define a generalized and ambiguous concept, such as piety or love. After the answer is given, Socrates will follow up with another question aimed at revealing a contradiction in the response, an exception to it, or something else that is problematic. The questioning and answering then continues until one has the impression that there are no clear answers. Modern use of the Socratic Method: ● The Socratic method is still used today in modern Law and legal systems. ● It does not only pertain to people involved in law systems, but anyone can use this method in communication. ● The Socratic approach involves a conversation in which a person is asked to question their assumptions. It is a forum for open-ended inquiry , one in which both student and teacher can use investigative questions to develop a deeper understanding of the topic. ● Ex.) In law school specifically, a professor will ask a series of socratic questions after having a student summarize a case, in an effort to dive deeper into the case and explore every possible court ruling or opposing argument.