Academic Eloquence and the End of Cicero's De Finibus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conversion of Skepticism in Augustine's Against the Academics the Conversion of Skepticism in Augustine"S Against the Academics

THE CONVERSION OF SKEPTICISM IN AUGUSTINE'S AGAINST THE ACADEMICS THE CONVERSION OF SKEPTICISM IN AUGUSTINE"S AGAINST THE ACADEMICS BY BERNARD NEWMAN WILLS, B.A., M.A. A THESIS Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor ofPhilosophy McMaster University C Copyright by Bernard Newman Wills DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2003) McMaster University (Religious Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Conversion of Skepticism in Augustine's Against the Academics AUTHOR: Bernard Newman Wills, B.A., M.A. SUPERVISOR: Dr. P. Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 322 ABSTRACT This thesis examines Augustine's relation to Academic Skepticism through a detailed commentary on the dialogue Against the Academics. In it is demonstrated the significance of epistemological themes for Augustine and their inseparability from practical and religious concerns. It is also shown how these issues unfold within the logic ofAugustine's trinitarianism, which informs the argument even ofhis earliest works. This, in turn, demonstrates the depth of the young Augustine's engagement with Christian categories in works often thought to be determined wholly, or almost wholly, by the logic of Plotinian Neo-Platonism. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Travis Kroeker for his advice and considerable patience: my readers Dr. Peter Widdicome and Dr. Zdravko Planinc: Dr. David Peddle for several useful suggestions and general encouragement: Dr. Dennis House for teaching me the art of reading dialogues: Mr. Danny Howlett for his editorial assistance: Grad Students and Colleagues at Memorial University of Newfoundland and, in a category all their own, my longsuffering wife Jean and three boisterous children Kristin, Jeremy and Thomas. -

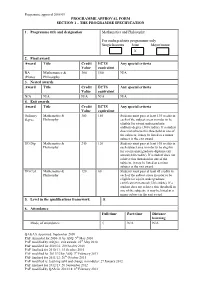

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Bibliography

Comp. by: C. Vijayakumar Stage : Revises1 ChapterID: 0002195881 Date:30/10/ 14 Time:14:12:02 Filepath://ppdys1122/BgPr/OUP_CAP/IN/Process/ 0002195881.3d243 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 30/10/2014, SPi Bibliography Accattino, P. (1985). Alessandro di Afrodisia e Aristotele di Mitelene. Elenchos 6, 67–74. Ackrill, J. L. (1962). Critical Notice: Die Aristotelische Syllogistik. By Gün- ther Patzig. Mind, 71, 107–17. Ackrill, J. L. (1963). Aristotle: Categories and De Interpretatione. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Ackrill, J. L. (1997). Essays on Plato and Aristotle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Adamson, P. (2005). On Knowledge of Particulars. Proceedings of the Aris- totelian Society, 105, 257–78. Adamson, P. (2007a). Knowledge of Universals and Particulars in the Bagh- dad School. Documenti e studi sulla tradizione filosofica medievale, 18, 141–64. Adamson, P. (2007b). Al-Kindī. New York: Oxford University Press. Adamson, P., Baltussen, H., and Stone, M. W. F. (eds). (2004). Philosophy, Science and Exegesis in Greek, Arabic, and Latin Commentaries. London: Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. Adamson, P., and Taylor, R. C. (eds). (2005). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Algra, K. A., van der Horst, P. W., and Runia, D. T. (eds). (1996). Polyhistor: Studies in the History and Historiography of Ancient Philosophy Presented to Jaap Mansfeld on his Sixtieth Birthday. Leiden: Brill. Allen, J. (2005). The Stoics on the Origin of Language and the Foundations of Etymology. In D. Frede and B. Inwood (eds), Language and Learning: Philosophy of Language in the Hellenistic Age, pp. 14–35. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Allen, R. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

'The Supreme Principle of Morality'? in the Preface to His Best

The Supreme Principle of Morality Allen W. Wood 1. What is ‘The Supreme Principle of Morality’? In the Preface to his best known work on moral philosophy, Kant states his purpose very clearly and succinctly: “The present groundwork is, however, nothing more than the search for and establishment of the supreme principle of morality, which already constitutes an enterprise whole in its aim and to be separated from every other moral investigation” (Groundwork 4:392). This paper will deal with the outcome of the first part of this task, namely, Kant’s attempt to formulate the supreme principle of morality, which is the intended outcome of the search. It will consider this formulation in light of Kant’s conception of the historical antecedents of his attempt. Our first task, however, must be to say a little about the meaning of the term ‘supreme principle of morality’. For it is not nearly as evident to many as it was to Kant that there is such a thing at all. And it is extremely common for people, whatever position they may take on this issue, to misunderstand what a ‘supreme principle of morality’ is, what it is for, and what role it is supposed to play in moral theorizing and moral reasoning. Kant never directly presents any argument that there must be such a principle, but he does articulate several considerations that would seem to justify supposing that there is. Kant holds that moral questions are to be decided by reason. Reason, according to Kant, always seeks unity under principles, and ultimately, systematic unity under the fewest possible number of principles (Pure Reason A298-302/B355-359, A645- 650/B673-678). -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

Cicero and St. Augustine's Just War Theory: Classical Influences on a Christian Idea Berit Van Neste University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-12-2006 Cicero and St. Augustine's Just War Theory: Classical Influences on a Christian Idea Berit Van Neste University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Neste, Berit Van, "Cicero and St. Augustine's Just War Theory: Classical Influences on a Christian Idea" (2006). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3782 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cicero and St. Augustine's Just War Theory: Classical Influences on a Christian Idea by Berit Van Neste A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: James F. Strange, Ph.D. Paul G. Schneider, Ph.D. Michael J. Decker, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 12, 2006 Keywords: theology, philosophy, politics, patristic, medieval © Copyright 2006 , Berit Van Neste For Elizabeth and Calista Table of Contents Abstract ii Chapter 1 1 Introduction 1 Cicero’s Influence on Augustine 7 Chapter 2 13 Justice 13 Natural and Temporal Law 19 Commonwealth 34 Chapter 3 49 Just War 49 Chapter 4 60 Conclusion 60 References 64 i Cicero and St. -

Ennius Or Cicero? the Disreputable Diviners at Cic

ACTA CLASSICAXLIV(200/) 153-166 ISSN 0065-1141 ENNIUS OR CICERO? THE DISREPUTABLE DIVINERS AT CIC. DE DIV. 1.132 A.T. Nice University of the Witwatersrand ABSTRACT At the end of the first book of Cicero's De Divir1atior1e, Quintus remarks that, even though he believes in divination, there are some diviners whom he would not trust to give accurate predictions. These comments are followed by a quotation from Ennius' Telamo. Most modem scholars have assumed, therefore, that the previous lines also contain an echo, if not a paraphrase of Ennius' work. This supposition does not seem to be supported by the language or style employed by Cicero. The lines should rather be understood as embodying the parochial view that elite Romans had towards forms of divination that were foreign, rustic or mercenary and not practised by the Roman state. I At the end of the first book of De Divinatione ( 1.132), Quintus completes his argument in favour of divination by denying the respectability of certain kinds ofdiviners: Nunc illa testabor, non me sortilegos neque eos, qui quaestus causa hariolentur, ne psychomantia quidem, quibus Appius, amicus tuus, uti solebat, agnoscere; non habeo denique nauci Marsum augurem, non vicanos haruspices, non de circo astrologos, non Isiacos coniectores, non interpretes somniorum; non enim sunt ii aut scientia aut arte divini. 1 The lines that follow, '(sed)2 superstitiosi vates inpudentes harioli ... de his di vitiis sibi deducant drachmam, reddant cetera,' are normally attributed to Ennius. Some previous commentators considered that the Ennius quotation should begin earlier, specifically from 'non habeo denique nauci.' 3 In favour 1 I use here the Teubner edition of R. -

On Unitarian Universalist Moral Duties: Looking Forward with Cicero and Kant

On Unitarian Universalist Moral Duties: Looking Forward with Cicero and Kant Myriam Renaud I. Why Moral Duties? Aren‟t We Done With That Conversation? For the purposes of this paper, I will rely on the following definition of moral duty (or obligation): an action which is required (imperative) and which is guided by certain moral rules and principles. In every day language, we capture the concept of duty or obligation when we say things like, “I should [or „ought‟] to do this because it‟s the right thing to do,” or “I want to do right by so and so.” These ordinary expressions reflect the view that awareness of the rightness of an action may be enough to provide the impetus to carry through that action—namely, that “in acting from a motive attached to a moral principle,”—in acting on what we take to be the right thing to do—“the moral rightness of the action gives the agent reason for action” [Herman, 30]. Admittedly, the word alone—duty—is likely to cause unpleasant shivers to course down the spines of most Unitarian Universalists. It brings to mind something we have to do, something we‟d rather not do, something we‟re made to do, probably at the expense of some activity we would actually enjoy. But, if we push past the unpleasant shiver, we recognize that duty, or obligation, is tied to the moral structure which governs our lives and which we try to impart to our children both at home and in the religious education classes offered in our congregations. -

Gulino 1 Pleasure and the Stoic Sage a Thesis Presented to the Honors

Gulino 1 Pleasure and the Stoic Sage A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College of Ohio University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy By Kathleen R. Gulino June 2011 Gulino 2 Table of Contents Sources and Abbreviations 2 Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Οἰκείωζις 9 Chapter 2: Χαρά 25 Conclusions 42 References 50 Gulino 3 Sources and Abbreviations Throughout this work, I cite several traditional sources for Stoic and Hellenistic texts. Here I have provided a list of the abbreviations I will use to refer to those texts. The References page lists the specific editions from which I have cited. Fin. Cicero, De Finibus (On Moral Ends) NA Gellius, Noctes Atticae (Attic Nights) Div. Inst. Lactantius, Divine Institutes DL Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers LS A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley, The Hellenistic Philosophers Ep. Seneca, Epistulae (Letters) Gulino 4 Introduction. The Hellenistic period refers, generally speaking, to the years beginning with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and ending with the downfall of the Roman Republic, considered as Octavian‘s victory at the battle of Actium, in 31 BCE. Philosophy was a Greek activity throughout this period, and at the outset, the works of Plato and Aristotle were the main texts used in philosophical study. However, as the Hellenistic culture came into its own, philosophy came to be dominated by three schools unique to the period: Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Skepticism. All of these, having come about after Aristotle, are distinctively Hellenistic, and it was these schools that held primary influence over thought in the Hellenistic world, at least until the revival of Platonism during the first century.1 Today, in the English-speaking world, the names of these traditions are still familiar, remaining in popular usage as ordinary adjectives. -

Ciceronian Business Ethics Owen Goldin Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Philosophy Faculty Research and Publications Philosophy, Department of 11-1-2006 Ciceronian Business Ethics Owen Goldin Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Studies in the History of Ethics (November 2006). Publisher link. © 2006 HistoryofEthics.org. Used with permission. Studies in the History of Ethics Ciceronian Bu siness Ethics Owen Goldin (Mar quette University) The teaching and practice of business must resist ethical compartmentalization. One engaged in business ought not check moral principles at the door and say “business is business,” for this is to pretend that when one is engaged in business, one is no longer a human being, with the rational nature, emotional constitution, and social bonds that are at the root of our ethical nature. Ethical standards apply to business as they do all aspects of human life. Nonetheless, making money is the goal of business, and more often than not, one is trying to take money from another, at the least possible cost. Such action is necessarily self-centered, if not selfish, and requires acting in a way that we would not want to see people act in all of their dealings with others, especially in regard to family, friends, and others with whom they have special social bonds. Granting that business practices are not compartmentalized against all ethical considerations, the fact that business demands maximization of profit entails that special rules apply. Determining what these are, in what circumstances they are less demanding than the ethical principles of everyday life, and in what circumstances they are more demanding, is the domain of business ethics, as a special domain of ethical philosophy. -

The Stoics and the Practical: a Roman Reply to Aristotle

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 8-2013 The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle Robin Weiss DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Weiss, Robin, "The Stoics and the practical: a Roman reply to Aristotle" (2013). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 143. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/143 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STOICS AND THE PRACTICAL: A ROMAN REPLY TO ARISTOTLE A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2013 BY Robin Weiss Department of Philosophy College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, IL - TABLE OF CONTENTS - Introduction……………………..............................................................................................................p.i Chapter One: Practical Knowledge and its Others Technê and Natural Philosophy…………………………….....……..……………………………….....p. 1 Virtue and technical expertise conflated – subsequently distinguished in Plato – ethical knowledge contrasted with that of nature in