Classical Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

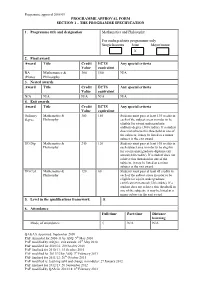

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

Remembering Socrates Philosophical Essays

Remembering Socrates Philosophical Essays Edited by LINDSAY JUDSON and VASSILIS KARASMANIS CLARENDON PRESS Á OXFORD 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß the several contributors 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd., King’s Lynn, Norfolk ISBN 0-19-927613-7 978-0-19-927613-4 13579108642 Contents Notes on Contributors and Editors vii Introduction 1 1. -

Index Locorum

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11015-1 — The Aporetic Tradition in Ancient Philosophy Edited by George Karamanolis , Vasilis Politis Index More Information Index Locorum Alcinous Anonymous Didaskalikos Theaetetus Commentary 4.6, 195 49–56, 193 Alexander of Aphrodisias Aristophanes On the Metaphysics (in Meta.) Clouds, 38 173, 27–174, 4, 239 Aristotle 200, 18–21, 236 Generation of Animals 206, 12–13, 240 716b12–13, 167 210, 20–1, 240 717a30–31, 168 212, 25–7, 242 717a5, 163 212, 27–35, 242 718a35–37, 167 213, 11–13, 243 718a36–37, 167 213, 19–23, 242 719b33–34, 168 213, 26–214, 17, 243 720b21, 163 213, 3–10, 243 728b32–4, 159 214, 24–215, 18, 244 732a32, 159 216, 8–11, 246 733b32, 160 218, 17, 240 733b32–734a4, 160 263, 26–29, 240 734a10, 161 On the Topics (in Top.) 734a11–13, 161 1.1, 17, 3, 244 734a13–14, 161 29, 23–30, 9, 233 734a14–16, 161 29, 30–31, 233 734a5–6, 161 3, 4–24, 232 734a7–8, 161 30, 12–18, 234 734a9–10, 161 30, 18–31, 4, 236 734b1–2, 161 32, 12–34, 5, 239 734b18, 162 32, 17–20, 238 734b4–7, 161 32, 22–26, 238 734b7–19, 162 458, 26–459, 3, 229 734b8–9, 161 Problems and Solutions (Quaest.) 735a29, 166 1.11, 245 735a29–736a23, 158 1.17, 245 735a5–7, 161 1.26, 245 735b7–8, 158 1.3, 245 736a24, 166 1.8, 245 738b7, 163 2.27, 243 740b2–5, 159 Suppliment to On the Soul (Mantissa) 740b2–8, 166 5, 245 740b5–8, 160 300 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11015-1 — The Aporetic Tradition in Ancient Philosophy Edited by George Karamanolis , Vasilis Politis Index -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83366-0 — Plato's Essentialism Vasilis Politis Excerpt More Information Introduction The topic of the present study is Plato’s theory of Forms, as it used to be called. The thesis of the study is that Plato’s Forms simply are essences and that Plato’s theory of Forms is a theory of essence – essences, in the sense of what we are committed to by the supposition that the ti esti (‘What is it?’) question can be posed and, all going well, answered. This thesis says that the characteristics that, as is generally recognised, Plato attributes to Forms, he attributes to them because he thinks that it can be shown that essences, on the original and minimal sense of essence, must be so characterised. The characteristics that Plato attributes to Forms include the following: Forms are changeless, uniform, not perceptible by the senses, knowable only by reasoning, the basis of causation and explanation, distinct from sense-perceptible things, necessary for thought and speech, separate from physical things. According to the thesis of this study, each and all of these characteristics of Forms can be derived, Plato thinks, from the supposition that we can ask and, all going well, answer the ti esti question adequately and truly, and the supposition that, whatever else Forms are and is characteristic of them, they are essences, essences in the sense of that which is designated by an adequate and true answer to the ti esti question. For Plato, the question ‘What is ...?’ is not, originally and according to its original meaning and use – the meaning and use shared by Socrates’ understanding of it and the understanding of it by his interlocutors – a philosophical, much less technical question, the posing of which commits one to the existence of essences in a disputable or controversial sense. -

Larissa Aronin, Vasilis Politis Multilingualism As an Edge

Larissa Aronin, Vasilis Politis Multilingualism as an Edge Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition 1/1, 27-49 2015 Theory and Practice of Second Language Acquisition vol. 1 (1) 2015, pp. 27–49 Larissa Aronin Oranim Academic College of Education, Israel Vasilis Politis Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland Multilingualism as an Edge* A b s t r a c t: The article presents a philosophical conceptualization of multilingualism. Philo- sophy’s general task is to subject human experience to reflective scrutiny and the experience of present day society has changed drastically. Multilingualism, as the vehicle of a new lin- guistic dispensation, plays a central role in it. We apply the metaphor ‘edge’ to explore the way multiple languages are deployed in, and intensively shape, the postmodern world. We also demonstrate how multilingualism is an edge, not only metaphorically, but involving true and real boundaries of various kinds, and all of them are essential for its nature. K e y w o r d s: philosophy, multilingualism, boundaries, edge Introduction Multilingualism is currently a thriving area of enquiry. It is being researched from a variety of angles and has amassed an impressive and diverse pool of data. Theoretical knowledge on multilingualism is expanding too. It concerns social organization, the role of languages, and a wider vision of the universe in which speaking and thinking man, homo loquens, exists. Research methodology on multilingualism allows for a wide range of ap- proaches. While a great diversity of traditional methods of psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic research continues to be intensively employed by scholars, a significant change is taking place as new methods are developed or being borrowed from neighboring disciplines, and also from seemingly distant ones * The research work of the first author of this article was supported by the Visiting Research Fellowship at the Trinity Long Room Hub Arts and Humanities Research Institute, TCD, Dublin, Ireland. -

Department Newsletter, 2018

Yale Department of Classics Summer 2018 Greetings from the Chair: As you’ll see on pp. 10-11, same time, we expect students to acquire familiarity with at a conservative estimate the history of classical scholarship and protean receptions this past year the Classics of classical antiquity. All the while, in the tradition of the department organized liberal arts, students bring the insights of many disciplines or co-sponsored a and different theoretical frames to their work and subject staggering sixty-four the study of antiquity to “wake work,” in Christina Sharpe’s events, prompting us to formulation, troubling our relationship with the past. In realize that there is an short, we try to train our students to be cosmonauts of upper limit to the number ancient Mediterranean civilizations and their afterlives: of lectures, seminars, and capable of interpreting both antiquity’s realia and its other events compatible fantasies and of analyzing modern fantasies about antiquity. with a good life. The last This May we graduated ten majors, five of whom were event of the year was decidedly glukupikros (sweetbitter), double majors and all of whom demonstrated this impressive as we celebrated Professor Victor Bers’s career at Yale, spanning range in their work. We congratulate Giorgio Caturegli, forty-six years: sweet as we celebrated Victor’s scholarly Luke Chang, Nicholas Dell Isola, Paul Eberwine, Sherry achievements and his extraordinarily generous mentorship Lee, Courtney Screen, Deniz Tanyolac, Victor Wang, Eli of generations of scholars, bitter as we contemplated his Westerman, and Nina Zoubek. With fourteen rising seniors, retirement. You can read more about this event on p. -

Academic Eloquence and the End of Cicero's De Finibus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository ACADEMIC ELOQUENCE AND THE END OF CICERO’S DE FINIBUS * A.G.Long Abstract The paper considers why the structure of Cicero’s De Finibus implicitly favours the Academy, even though Cicero avoids a decision between the Stoic theory and Antiochus’ theory. Cicero’s educational aims require him to illustrate not only a range of theories but a range of criteria by which theories and the exposition of theories should be judged. By one criterion – style of exposition – the entire Academic tradition, not Antiochus specifically, is endorsed. Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum stages debates between exponents and critics of three ethical theories, with the part of critic taken by Cicero himself in each of the three debates. The first theory is Epicurean, the second Stoic; the third is harder to label, as it is attributed by Cicero not to a single philosopher or school but to a trio: Antiochus, Peripatetics and the so-called ‘Old Academy’ (v 8; cf. ii 34 and v 21). Like others I shall refer to it as the ‘Antiochian’ theory, but it is important to keep in mind Cicero’s claim (which evidently derives from Antiochus himself, v 14) that the theory’s provenance is pre-Antiochian too. In the survey of his philosophical writing in De Divinatione Cicero says that his aim in writing De Finibus was to make known the arguments for and against each of the philosophers’ theories (ii 2). -

Accessible Syllabus Template

PHIL620 (22677) PHILOSOPHY of TIME a cross-cultural analysis SPRING 2015 COURSE INFORMATION Class Days: Monday Class Times: 4-6:40 p.m. Class Location: AL 422 Office Hours Times: TTH 11-12; M 2:30-3:30 (or by appointment) Office Hours Location: AL473A [email protected] 1 Course Overview Description from the Official Course Catalog 630 Seminar in Philosophical Problems: Knowledge and Reality (3) A problem or group of problems in metaphysics, epistemology and logic. Description of the Purpose and Course Content Time is a concept that has presented perennial challenges to philosophers from all cultures for thousands of years. It also has a prominent role in theories still unfolding in post-modern science. We will begin with a sampling of Eurocentric theories and reveries concerning Time: Augustine to Wittgenstein Kant and the Mad Hatter’s Tea/Time Party Nietzsche’s Eternal Recurrence Krishnamurti Then we will examine notions of time in Buddhism Diamond Sūtra that resonate with post-modern science, as heralded by Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and space-time continuum. Eight hundred years before Heidegger, Zen Master Dōgen (1200-1253) was parsing the experience of Uji, Time-Being, encountered in the perceptual revolution provoked by Buddhist practice that can lead to epistemological awakening. Student Learning Outcomes 1. Investigate and analyze interdisciplinary approaches to philosophical questions posed by Time in multiple cultures 2. Assess theories on Time offered by philosophers and the scientists 3. Evaluate the evidence garnered from various disciplines by proposing and testing a hypothesis/theorem concerning Time 4. Explore the personal and global consequences of our assumptions about Time Real Life Relevance “Time is not an empirical concept. -

Kant on Judgment

Routledge Philosophy GuideBook to Kant on Judgment “This is a superb treatment of Kant’s third Critique in its entirety – in depth, in careful analysis, and in understanding in a way not articu- lated by others of the integration of Kant’s aesthetic theory with the rest of his philosophy.” Donald W. Crawford, Emeritus Professor of Philosophy, University of California, Santa Barbara Kant’s Critique of Judgment is one of the most important texts in the his- tory of modern aesthetics. This GuideBook discusses the third Critique section by section, and introduces and assesses: • Kant’s life and the background of the Critique of Judgment • The ideas and text of the Critique of Judgment, including a critical explanation of Kant’s theories of natural beauty • The continuing relevance of Kant’s work to contemporary philosophy and aesthetics. This GuideBook is an accessible introduction to a notoriously difficult work and will be essential reading for students of Kant and aesthetics. Robert Wicks is Associate Professor of Philosophy at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. ROUTLEDGE PHILOSOPHY GUIDEBOOKS Edited by Tim Crane and Jonathan Wolff, University College London Plato and the Trial of Socrates Thomas C. Brickhouse and Nicholas D. Smith Aristotle and the Metaphysics Vasilis Politis Rousseau and The Social Contract Christopher Bertram Plato and the Republic, Second Edition Nickolas Pappas Husserl and the Cartesian Meditations A.D. Smith Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling John Lippitt Descartes and the Meditations Gary Hatfield Hegel and -

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department Of

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department of Philosophy Princeton University Phone: (609) 258 4300 Email: [email protected] Academic Employment Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2012 – present Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2007 – 2012 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2001 – 2007 Lecturer in Philosophy, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 2000 – 2001 Junior Research Fellow, St John’s College, Oxford, 1999 – 2001 Lecturer in Philosophy, New College, Oxford, 1998 – 1999 Education D. Phil., Philosophy, University of Oxford, October 2000 M. Phil., Ancient Philosophy, University of Cambridge, September 1996 B. A., Classics, University of Cambridge, September 1995 Area of Specialization Ancient Philosophy Honors and Awards Behrman Fellow in the Humanities, Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, 2007–2009 Robert K. Root University Preceptorship, Princeton University, 2005–2008 Publications “Aristotle’s Empiricist Theory of Doxastic Knowledge,” with Benjamin Morison (under review) 1 “Intelligence as Cause: P hilebus 2 7c31b,” P lato Dialogue Project: Plato’s P hilebus, ed. by Panos Dimas, Gabriel Lear, and Russell Jones (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) “The Principles of Natural Things: Two or Three? Aristotle, P hysics I 7, 190b17191a22,” Symposium Aristotelicum on P hysics Book I, ed. by Katerina Ierodiakonou and Paul Kalligas (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) Review of Christopher Shields, Aristotle : De Anima, T ranslation, Introduction and Commentary, in N otre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 2 017 “Natural Goals of Actions in Aristotle,” J ournal of the American Philosophical Association, Volume 1, Issue 4, Winter 2015, 583–600 “Aristotle’s analysis of akratic action,” in R. Polansky (ed.), T he Cambridge Companion to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 2014), 242–262 “Understanding, knowledge, and inquiry in Aristotle,” in F. -

The Birth of Belief, (PDF)

The Birth of Belief Jessica Moss (NYU) and Whitney Schwab (UMBC)* Forthcoming in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 1 Introduction Did Plato and Aristotle have anything to say about belief? The answer to this question might seem blindingly obvious: of course they did. Plato distinguishes belief from knowledge in the Meno, Republic, and Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the Posterior Analytics. Plato distinguishes belief from perception in the Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the de Anima. They talk about the distinction between true and false beliefs, and the ways in which belief can mislead and the ways in which it can steer us aright. Indeed, they make belief a central component of their epistemologies. The view underlying these claims—one so widespread these days as to remain largely unquestioned—is that when Plato and Aristotle talk about doxa, they are talking about what we now call belief. Or, at least, they are talking about something so closely related to what we now call belief that no philosophical importance can be placed on any differences. Doxa is the ancient counterpart of belief: hence, the use nowadays of ‘doxastic' as the adjective corresponding to ‘belief.' One of our aims in this paper is to challenge this view. We argue that Plato and Aristotle raise questions and advance views about doxa that would be very strange if they concerned belief. This suggests either that Plato and Aristotle had very strange ideas about belief, or that doxa is not best understood as belief. We argue for the latter option by pursuing our second aim, which is to show that Aristotle, expanding on ideas suggested in Plato, explicitly develops a notion that corresponds much more closely to our modern notion of belief: hupolepsis.