The Birth of Belief, (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Skepticism and Pluralism Ways of Living a Life Of

SKEPTICISM AND PLURALISM WAYS OF LIVING A LIFE OF AWARENESS AS RECOMMENDED BY THE ZHUANGZI #±r A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHILOSOPHY AUGUST 2004 By John Trowbridge Dissertation Committee: Roger T. Ames, Chairperson Tamara Albertini Chung-ying Cheng James E. Tiles David R. McCraw © Copyright 2004 by John Trowbridge iii Dedicated to my wife, Jill iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In completing this research, I would like to express my appreciation first and foremost to my wife, Jill, and our three children, James, Holly, and Henry for their support during this process. I would also like to express my gratitude to my entire dissertation committee for their insight and understanding ofthe topics at hand. Studying under Roger Ames has been a transformative experience. In particular, his commitment to taking the Chinese tradition on its own terms and avoiding the tendency among Western interpreters to overwrite traditional Chinese thought with the preoccupations ofWestern philosophy has enabled me to broaden my conception ofphilosophy itself. Roger's seminars on Confucianism and Daoism, and especially a seminar on writing a philosophical translation ofthe Zhongyong r:pJm (Achieving Equilibrium in the Everyday), have greatly influenced my own initial attempts to translate and interpret the seminal philosophical texts ofancient China. Tamara Albertini's expertise in ancient Greek philosophy was indispensable to this project, and a seminar I audited with her, comparing early Greek and ancient Chinese philosophy, was part ofthe inspiration for my choice ofresearch topic. I particularly valued the opportunity to study Daoism and the Yijing ~*~ with Chung-ying Cheng g\Gr:p~ and benefited greatly from his theory ofonto-cosmology as a means of understanding classical Chinese philosophy. -

Aristotle's Assertoric Syllogistic and Modern Relevance Logic*

Aristotle’s assertoric syllogistic and modern relevance logic* Abstract: This paper sets out to evaluate the claim that Aristotle’s Assertoric Syllogistic is a relevance logic or shows significant similarities with it. I prepare the grounds for a meaningful comparison by extracting the notion of relevance employed in the most influential work on modern relevance logic, Anderson and Belnap’s Entailment. This notion is characterized by two conditions imposed on the concept of validity: first, that some meaning content is shared between the premises and the conclusion, and second, that the premises of a proof are actually used to derive the conclusion. Turning to Aristotle’s Prior Analytics, I argue that there is evidence that Aristotle’s Assertoric Syllogistic satisfies both conditions. Moreover, Aristotle at one point explicitly addresses the potential harmfulness of syllogisms with unused premises. Here, I argue that Aristotle’s analysis allows for a rejection of such syllogisms on formal grounds established in the foregoing parts of the Prior Analytics. In a final section I consider the view that Aristotle distinguished between validity on the one hand and syllogistic validity on the other. Following this line of reasoning, Aristotle’s logic might not be a relevance logic, since relevance is part of syllogistic validity and not, as modern relevance logic demands, of general validity. I argue that the reasons to reject this view are more compelling than the reasons to accept it and that we can, cautiously, uphold the result that Aristotle’s logic is a relevance logic. Keywords: Aristotle, Syllogism, Relevance Logic, History of Logic, Logic, Relevance 1. -

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

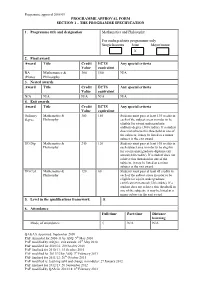

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Stoic Enlightenments

Copyright © 2011 Margaret Felice Wald All rights reserved STOIC ENLIGHTENMENTS By MARGARET FELICE WALD A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in English written under the direction of Michael McKeon and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Stoic Enlightenments By MARGARET FELICE WALD Dissertation Director: Michael McKeon Stoic ideals infused seventeenth- and eighteenth-century thought, not only in the figure of the ascetic sage who grins and bears all, but also in a myriad of other constructions, shaping the way the period imagined ethical, political, linguistic, epistemological, and social reform. My dissertation examines the literary manifestation of Stoicism’s legacy, in particular regarding the institution and danger of autonomy, the foundation and limitation of virtue, the nature of the passions, the difference between good and evil, and the referentiality of language. Alongside the standard satirical responses to the ancient creed’s rigor and rationalism, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century poetry, drama, and prose developed Stoic formulations that made the most demanding of philosophical ideals tenable within the framework of common experience. Instead of serving as hallmarks for hypocrisy, the literary stoics I investigate uphold a brand of stoicism fit for the post-regicidal, post- Protestant Reformation, post-scientific revolutionary world. My project reveals how writers used Stoicism to determine the viability of philosophical precept and establish ways of compensating for human fallibility. The ambivalent status of the Stoic sage, staged and restaged in countless texts, exemplified the period’s anxiety about measuring up to its ideals, its efforts to discover the plenitude of ii natural laws and to live by them. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Originally translated by Meric Casaubon About this edition Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus was Emperor of Rome from 161 to his death, the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He was nephew, son-in-law, and adoptive son of Antonius Pius. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most important Stoic philosophers, cited by H.P. Blavatsky amongst famous classic sages and writers such as Plato, Eu- ripides, Socrates, Aristophanes, Pindar, Plutarch, Isocrates, Diodorus, Cicero, and Epictetus.1 This edition was originally translated out of the Greek by Meric Casaubon in 1634 as “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius,” with an Introduction by W.H.D. Rouse. It was subsequently edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J.M. Dent & Co; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1906; Everyman’s Library. 1 Cf. Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE ORIGIN OF THE MYSTERIES) XIV p. 257 Marcus Aurelius' Meditations - tr. Casaubon v. 8.16, uploaded to www.philaletheians.co.uk, 14 July 2013 Page 1 of 128 LIVING THE LIFE SERIES MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUS Chief English translations of Marcus Aurelius Meric Casaubon, 1634; Jeremy Collier, 1701; James Thomson, 1747; R. Graves, 1792; H. McCormac, 1844; George Long, 1862; G.H. Rendall, 1898; and J. Jackson, 1906. Renan’s “Marc-Aurèle” — in his “History of the Origins of Christianity,” which ap- peared in 1882 — is the most vital and original book to be had relating to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Pater’s “Marius the Epicurean” forms another outside commentary, which is of service in the imaginative attempt to create again the period.2 Contents Introduction 3 THE FIRST BOOK 12 THE SECOND BOOK 19 THE THIRD BOOK 23 THE FOURTH BOOK 29 THE FIFTH BOOK 38 THE SIXTH BOOK 47 THE SEVENTH BOOK 57 THE EIGHTH BOOK 67 THE NINTH BOOK 77 THE TENTH BOOK 86 THE ELEVENTH BOOK 96 THE TWELFTH BOOK 104 Appendix 110 Notes 122 Glossary 123 A parting thought 128 2 [Brought forward from p. -

Humanism and Neo-Stoicism." War and Peace in the Western Political Imagination: from Classical Antiquity to the Age of Reason

Manning, Roger B. "Humanism and Neo-Stoicism." War and Peace in the Western Political Imagination: From Classical Antiquity to the Age of Reason. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 181–214. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474258739.ch-004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 04:18 UTC. Copyright © Roger B. Manning 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 4 H u m a n i s m a n d N e o - S t o i c i s m No state . can support itself without an army. Niccolò Macchiavelli, Th e Art of War , trans. Ellis Farneworth (Indianapolis, IN : Bobbs-Merrill, 1965; rpr. New York: Da Capo, 1990), bk. 1, p. 30 Rash princes, until such times as they have been well beaten in the wars, will always have little regard for peace. Antonio Guevara, Bishop of Guadix, Th e Diall of Princes , trans. Th omas North (London: John Waylande, 1557; rpr. Amsterdam: Th eatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1968), fo. 174v Th e Humanist response to the perpetual problems of war and peace divided into the polarities of a martial ethos and an irenic or peace- loving culture. Th ese opposing cultures were linked to an obsession with fame or reputation, honor, and the military legacy of ancient Greece and Rome on the one hand, and on the other, a concern with human dignity, freedom, and a stricter application of Christian morality. -

Marko Malink (NYU)

Demonstration by reductio ad impossibile in Posterior Analytics 1.26 Marko Malink (New York University) Contents 1. Aristotle’s thesis in Posterior Analytics 1. 26 ................................................................................. 1 2. Direct negative demonstration vs. demonstration by reductio ................................................. 14 3. Aristotle’s argument from priority in nature .............................................................................. 25 4. Priority in nature for a-propositions ............................................................................................ 38 5. Priority in nature for e-, i-, and o-propositions .......................................................................... 55 6. Accounting for Aristotle’s thesis in Posterior Analytics 1. 26 ................................................... 65 7. Parts and wholes ............................................................................................................................. 77 References ............................................................................................................................................ 89 1. Aristotle’s thesis in Posterior Analytics 1. 26 At the beginning of the Analytics, Aristotle states that the subject of the treatise is demonstration (ἀπόδειξις). A demonstration, for Aristotle, is a kind of deductive argument. It is a deduction through which, when we possess it, we have scientific knowledge (ἐπιστήμη). While the Prior Analytics deals with deduction in -

C.S. Peirce's Abduction from the Prior Analytics

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Community Scholar Publications Providence College Community Scholars 7-1996 C.S. Peirce's Abduction from the Prior Analytics William Paul Haas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/comm_scholar_pubs Haas, William Paul, "C.S. Peirce's Abduction from the Prior Analytics" (1996). Community Scholar Publications. 2. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/comm_scholar_pubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Providence College Community Scholars at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Scholar Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM PAUL HAAS July 1996 C.S. PEIRCE'S ABDUCTION FROM THE PRIOR ANALYTICS In his Ancient Formal Logic. Professor Joseph Bochenski finds Aristotle's description of syllogisms based upon hypotheses to be "difficult to understand." Noting that we do not have the treatise which Aristotle promised to write, Bochenski laments the fact that the Prior Analytics, where it is treated most explicitly, "is either corrupted or (which is more probable) was hastily written and contains logical errors." (1) Charles Sanders Peirce wrestled with the same difficult text when he attempted to establish the Aristotelian roots of his theory of abductive or hypothetical reasoning. However, Peirce opted for the explanation that the fault was with the corrupted text, not with Aristotle's exposition. Peirce interpreted the text of Book II, Chapter 25 thus: Accordingly, when he opens the next chapter with the word ' Ajray (¿y-q a word evidently chosen to form a pendant to 'Errctyuyrj, we feel sure that this is what he is coming to. -

Aristoxenus Elements of Rhythm: Text, Translation, and Commentary with a Translation and Commentary on Poxy 2687

© 2009 Christopher C. Marchetti ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ARISTOXENUS ELEMENTS OF RHYTHM: TEXT, TRANSLATION, AND COMMENTARY WITH A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY ON POXY 2687 by CHRISTOPHER C. MARCHETTI A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Classics written under the direction of Prof. Thomas Figueira and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2009 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Aristoxenus’ Elements of Rhythm: Text, Translation, and Commentary with a Translation and Commentary on POxy 2687 By Christopher C. Marchetti Dissertation Director: Prof. Thomas Figueira Aristoxenus of Tarentum makes productive use of Aristotelian concepts and methods in developing his theory of musical rhythm in his treatise Elements of Rhythm. He applies the Aristotelian distinction between form and material and the concept of hypothetical necessity to provide an explanation for why musical rhythm is manifested in the syllables of song, the notes of melody, and the steps of dance. He applies the method of formulating differentiae, as described in Aristotle’s Parts of Animals, to codify the formal properties of rhythm. Aristoxenus’ description of the rhythmic foot presents several interpretive challenges. Our text is fragmentary, and we lack Aristoxenus’ definitions of several key terms. This study seeks to establish the meanings of these terms on the basis of a close examination of the structure of Aristoxenus’ argument. Parallel passages in Aristides Quintilianus’ On Music are considered in detail for ii their consistency or lack thereof with Aristoxenian usage. -

Plato's Basic Metaphysical Argument Against Hedonism and Aristotle's Presentation of It at Eudemian Ethics 6.11

Plato's Basic Metaphysical Argument against Hedonism David Wolfsdorf and Aristotle's Presentation of It at Eudemian Ethics 6.11 1. Introduction At Eudemian Ethics 6.11 (= Nicomachean Ethics 7.11) Aristotle introduces several views that others hold regarding pleasure's value. In particular I draw your attention to the following one. Aristotle writes that some believe that: A. No pleasure is a good thing, either in itself or incidentally. οὐδεµία ἡδονὴ εἶναι ἀγαθόν, οὔτε καθ᾽ αὑτὸ οὔτε κατὰ συµβεβηκός. (1152b8-9) Aristotle proceeds to give several reasons for this position. One is that: R. Every pleasure is a perceived genesis toward a nature, but no genesis is of the same kind as its ends, for example no building of a house is of the same kind as a house. (1152b13-15) πᾶσα ἡδονὴ γένεσίς ἐστιν εἰς φύσιν αἰσθητή, οὐδεµία δὲ γένεσις συγγενὴς τοῖς τέλεσιν, οἷον οὐδεµία οἰκοδόµησις οἰκίᾳ. Who are the believers of A and R that Aristotle is reporting? I suggest that the evidence leads us back to Plato's Philebus. There a view very similar to R is developed, and a view very similar to A is argued to depend on it. That the views Aristotle here reports can be traced back to Plato does not confirm that Plato himself held them. An argument is always necessary when inferring from a thesis stated or advanced in some Platonic text to a thesis maintained by Plato himself. But— setting that problem aside— I also said that A and R are "very similar to," I did not say that they were identical to the views expressed in Plato's Philebus. -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes.