THE VASSAR COLLEGE JOURNAL of PHLOSOPHY Issue 4 Spring 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

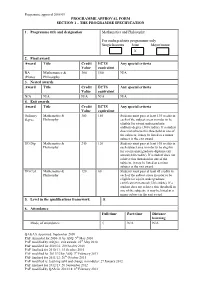

BA Mathematics and Philosophy

Programme approval 2008/09 PROGRAMME APPROVAL FORM SECTION 1 – THE PROGRAMME SPECIFICATION 1. Programme title and designation Mathematics and Philosophy For undergraduate programmes only Single honours Joint Major/minor X 2. Final award Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent BA Mathematics & 360 180 N/A (Hons) Philosophy 3. Nested awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A 4. Exit awards Award Title Credit ECTS Any special criteria Value equivalent Ordinary Mathematics & 300 150 Students must pass at least 135 credits in degree Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate ordinary degree (300 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award UG Dip Mathematics & 240 120 Students must pass at least 105 credits in Philosophy each subject area in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate diploma exit award (240 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. UG Cert Mathematics & 120 60 Students must pass at least 45 credits in Philosophy each of the subject areas in order to be eligible for a joint undergraduate certificate exit award (120 credits). If a student does not achieve this threshold in one of the subjects, it may be listed as a minor subject in the exit award. 5. Level in the qualifications framework H 6. -

Curriculum Vitae, April 2020

John P. F. Wynne Curriculum vitae, April 2020 Department of World Languages & Cultures, Languages & Communication Building, 255 S Central Campus Drive, Room 1400, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. [email protected] • Office: (801)-581-8384 Major research interests. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy and religion, especially of the Hellenistic and later periods; Cicero; philosophy of religion and philosophical skepticism. Other major teaching interests. Latin and ancient Greek literature; Augustine of Hippo, early Christian thought, and late antiquity. Employment. 2018- Associate Professor of Classics Department of World Languages & Cultures, University of Utah 2014-2018 Associate Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2008-2014 Assistant Professor of Classics, Northwestern University. 2007-8 College Fellow, Department of Classics, Northwestern University. Education. Jan 2003 - Jan 2008 PhD in Classics, Cornell University. Dissertation: Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. Committee: Charles Brittain, Terence Irwin, Hayden Pelliccia. Lane Cooper Fellow, 2006-2007. Fall 2002 Language study in Arabic with Persian at Durham University. 2001-2 Non-degree exchange graduate student in Classics, Cornell University. 1997-2001 BA (1st Hons.) in Literae Humaniores (= Classics), Oxford University. 1 Publications (most recent first). [1] ‘Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations: a sceptical reading.’ Accepted for publication in Summer 2020 edition of Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy. [2] ‘Cicero on the soul’s sensation of itself: Tusculans 1.49-76.’ Forthcoming (proofs corrected) in Brad Inwood and James Warren (eds.), Body and Soul in Hellenistic Philosophy, the published volume from the July 2016 Symposium Hellenisticum (see below). [3] Cicero on the philosophy of religion: On the nature of the gods and On divination. -

R V Ul-Haque

ARTICLES AXIOMS OF AGGRESSION Counter-terrorism and counter-productivity in Australia WALEED ALY t did not take Australia long to reach for a legislative that ‘[t]he questioning and detention powers which response to the terrorist attacks of September I I, were passed in 2003 by both Houses of Parliament 2001. Within months, the Federal government was have proved important in progressing a number of proposing new anti-terrorism legislation promoting investigations,’ while simultaneously affirming that ‘ASIO whatI has since become a familiar scheme: new species has not yet had to use the detention powers which were of offences relating to a statutorily-defined terrorism, always intended to be used only in the most exceptional and expanded powers for police and the Australian circumstances.’4 Presently, as the British government Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) enabling is facing considerable opposition to its proposal to REFERENCES them to detain and question a person who may have extend the available period of detention of terror 1. This ultimately found its expression in July 2002 in the form of the Security information useful in countering a terrorist attack suspects without charge from 28 days to 42, Home Legislation Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2002 — possibly without access to a lawyer for 48 hours.1 Secretary Jacqui Smith’s description of the new limit as (Cth), and a year later in the Australian a ‘safeguard’ to be used in exceptional circumstances Security Intelligence Organisation Legislation Thus began the most dramatic era in Australia’s counter rather than a ‘target’ rings familiarly. All the while Smith Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2003 (Cth). -

Review of Australia's Counter-Terrorism Machinery

© Commonwealth of Australia 2015 ISBN 978-1-925237-36-8 (Hardcopy) ISBN 978-1-925237-37-5 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-925237-38-2 (DOC) Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to below as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. The full licence terms are available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode. The Commonwealth’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Licensed from the Commonwealth of Australia under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the content of this publication. Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are set out on the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet website (see http://www.dpmc.gov.au/guidelines/). Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iv RECOMMENDATIONS vi PART ONE: THE STATE OF PLAY 1 One: Australia – Our Evolving -

The Virtual Entrepreneurs of the Islamic State

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Objective • Relevant • Rigorous | March 2017 • Volume 10, Issue 3 FEATURE ARTICLE FEATURE ANALYSIS The Virtual Entrepreneurs The Islamic of the Islamic State State’s War on How the group’s virtual planners threaten the United States Turkey Seamus Hughes and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens Ahmet S. Yayla FEATURE ARTICLE 1 The Threat to the United States from the Islamic State’s Virtual Editor in Chief Entrepreneurs Paul Cruickshank Seamus Hughes and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens Managing Editor FEATURE ANALYSIS Kristina Hummel 9 The Reina Nightclub Attack and the Islamic State Threat to Turkey Ahmet S. Yayla EDITORIAL BOARD Colonel Suzanne Nielsen, Ph.D. ANALYSIS Department Head Dept. of Social Sciences (West Point) 17 The German Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq: The Updated Data and its Implications Lieutenant Colonel Bryan Price, Ph.D. Daniel H. Heinke Director, CTC 23 Australian Jihadism in the Age of the Islamic State Brian Dodwell Andrew Zammit Deputy Director, CTC 31 The Taliban Stones Commission and the Insurgent Windfall from Illegal Mining Matthew C. DuPée CONTACT Combating Terrorism Center U.S. Military Academy In our feature article, Seamus Hughes and Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens 607 Cullum Road, Lincoln Hall focus on the threat to the United States from the Islamic State’s “virtual entrepreneurs” who have been using social media and encryption applica- West Point, NY 10996 tions to recruit and correspond with sympathizers in the West, encouraging and directing them to Phone: (845) 938-8495 engage in terrorist activity. They find that since 2014, contact with a virtual entrepreneur has been a Email: [email protected] feature of eight terrorist plots in the United States, involving 13 individuals. -

Classical Philosophy

Classical Philosophy “This is a fine introduction to ancient philosophy, consistently clear and carefully argued; interesting and generally attractive to read. I also enjoyed how the various views of the philosophers were successfully tied to overarching themes, such as the contrast between the manifest and the scientific image of the world.” Vasilis Politis, Trinity College, Dublin “I found the volume well organized and philosophically engaging. It doesn’t talk down to the reader, nor attempt to blind him/her with science (or philosophy), so it should be well suited for the intelligent non-expert.” Raphael Woolf, Harvard University The origins of Western philosophy can be found in sixth-century BC Greece. There it was that philosophy developed into a discipline that considered such fundamental questions as the nature of human existence, our place in the universe, and our attitudes towards an interactive politicized society. Every development in philosophy indeed stems from the thinkers of this enlightened time. Classical Philosophy is a comprehensive examination of early philosophy, from the Presocratics through to Aristotle. The aim of the book is to provide an explanation and analysis of the ideas that flourished at this time, and to consider their relevance, both to the historical development of philosophy and to contemporary philosophy today. From these ideas we can see the roots of arguments in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and political philosophy. The book is arranged in four parts by thinker and covers • the Presocratics • Socrates • Plato • Aristotle Christopher Shields’ style is inviting, refreshing, and ideal for anyone coming to the subject for the first time. -

Department Newsletter, 2018

Yale Department of Classics Summer 2018 Greetings from the Chair: As you’ll see on pp. 10-11, same time, we expect students to acquire familiarity with at a conservative estimate the history of classical scholarship and protean receptions this past year the Classics of classical antiquity. All the while, in the tradition of the department organized liberal arts, students bring the insights of many disciplines or co-sponsored a and different theoretical frames to their work and subject staggering sixty-four the study of antiquity to “wake work,” in Christina Sharpe’s events, prompting us to formulation, troubling our relationship with the past. In realize that there is an short, we try to train our students to be cosmonauts of upper limit to the number ancient Mediterranean civilizations and their afterlives: of lectures, seminars, and capable of interpreting both antiquity’s realia and its other events compatible fantasies and of analyzing modern fantasies about antiquity. with a good life. The last This May we graduated ten majors, five of whom were event of the year was decidedly glukupikros (sweetbitter), double majors and all of whom demonstrated this impressive as we celebrated Professor Victor Bers’s career at Yale, spanning range in their work. We congratulate Giorgio Caturegli, forty-six years: sweet as we celebrated Victor’s scholarly Luke Chang, Nicholas Dell Isola, Paul Eberwine, Sherry achievements and his extraordinarily generous mentorship Lee, Courtney Screen, Deniz Tanyolac, Victor Wang, Eli of generations of scholars, bitter as we contemplated his Westerman, and Nina Zoubek. With fourteen rising seniors, retirement. You can read more about this event on p. -

Academic Eloquence and the End of Cicero's De Finibus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository ACADEMIC ELOQUENCE AND THE END OF CICERO’S DE FINIBUS * A.G.Long Abstract The paper considers why the structure of Cicero’s De Finibus implicitly favours the Academy, even though Cicero avoids a decision between the Stoic theory and Antiochus’ theory. Cicero’s educational aims require him to illustrate not only a range of theories but a range of criteria by which theories and the exposition of theories should be judged. By one criterion – style of exposition – the entire Academic tradition, not Antiochus specifically, is endorsed. Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum stages debates between exponents and critics of three ethical theories, with the part of critic taken by Cicero himself in each of the three debates. The first theory is Epicurean, the second Stoic; the third is harder to label, as it is attributed by Cicero not to a single philosopher or school but to a trio: Antiochus, Peripatetics and the so-called ‘Old Academy’ (v 8; cf. ii 34 and v 21). Like others I shall refer to it as the ‘Antiochian’ theory, but it is important to keep in mind Cicero’s claim (which evidently derives from Antiochus himself, v 14) that the theory’s provenance is pre-Antiochian too. In the survey of his philosophical writing in De Divinatione Cicero says that his aim in writing De Finibus was to make known the arguments for and against each of the philosophers’ theories (ii 2). -

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department Of

CURRICULUM VITAE Hendrik Lorenz December 22, 2017 Department of Philosophy Princeton University Phone: (609) 258 4300 Email: [email protected] Academic Employment Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2012 – present Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2007 – 2012 Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, Princeton University, 2001 – 2007 Lecturer in Philosophy, Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 2000 – 2001 Junior Research Fellow, St John’s College, Oxford, 1999 – 2001 Lecturer in Philosophy, New College, Oxford, 1998 – 1999 Education D. Phil., Philosophy, University of Oxford, October 2000 M. Phil., Ancient Philosophy, University of Cambridge, September 1996 B. A., Classics, University of Cambridge, September 1995 Area of Specialization Ancient Philosophy Honors and Awards Behrman Fellow in the Humanities, Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, 2007–2009 Robert K. Root University Preceptorship, Princeton University, 2005–2008 Publications “Aristotle’s Empiricist Theory of Doxastic Knowledge,” with Benjamin Morison (under review) 1 “Intelligence as Cause: P hilebus 2 7c31b,” P lato Dialogue Project: Plato’s P hilebus, ed. by Panos Dimas, Gabriel Lear, and Russell Jones (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) “The Principles of Natural Things: Two or Three? Aristotle, P hysics I 7, 190b17191a22,” Symposium Aristotelicum on P hysics Book I, ed. by Katerina Ierodiakonou and Paul Kalligas (Oxford University Press, forthcoming) Review of Christopher Shields, Aristotle : De Anima, T ranslation, Introduction and Commentary, in N otre Dame Philosophical Reviews, 2 017 “Natural Goals of Actions in Aristotle,” J ournal of the American Philosophical Association, Volume 1, Issue 4, Winter 2015, 583–600 “Aristotle’s analysis of akratic action,” in R. Polansky (ed.), T he Cambridge Companion to Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 2014), 242–262 “Understanding, knowledge, and inquiry in Aristotle,” in F. -

The Birth of Belief, (PDF)

The Birth of Belief Jessica Moss (NYU) and Whitney Schwab (UMBC)* Forthcoming in the Journal of the History of Philosophy 1 Introduction Did Plato and Aristotle have anything to say about belief? The answer to this question might seem blindingly obvious: of course they did. Plato distinguishes belief from knowledge in the Meno, Republic, and Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the Posterior Analytics. Plato distinguishes belief from perception in the Theaetetus, and Aristotle does so in the de Anima. They talk about the distinction between true and false beliefs, and the ways in which belief can mislead and the ways in which it can steer us aright. Indeed, they make belief a central component of their epistemologies. The view underlying these claims—one so widespread these days as to remain largely unquestioned—is that when Plato and Aristotle talk about doxa, they are talking about what we now call belief. Or, at least, they are talking about something so closely related to what we now call belief that no philosophical importance can be placed on any differences. Doxa is the ancient counterpart of belief: hence, the use nowadays of ‘doxastic' as the adjective corresponding to ‘belief.' One of our aims in this paper is to challenge this view. We argue that Plato and Aristotle raise questions and advance views about doxa that would be very strange if they concerned belief. This suggests either that Plato and Aristotle had very strange ideas about belief, or that doxa is not best understood as belief. We argue for the latter option by pursuing our second aim, which is to show that Aristotle, expanding on ideas suggested in Plato, explicitly develops a notion that corresponds much more closely to our modern notion of belief: hupolepsis. -

CICERO COR/Applicationfiles/9781844658404 Text.3D

Template: Royal A, Font: , Date: 28/01/2015; 3B2 version: 10.0.1465/W Unicode (Dec 22 2011) (APS_OT) Dir: //integrafs1/kcg/2-Pagination/TandF/CICERO_COR/ApplicationFiles/9781844658404_text.3d CICERO Cicero’s philosophical works introduced Latin audiences to the ideas of the Stoics, Epicureans and other schools and figures of the post-Aristotelian period, thus influencing the transmission of those ideas through later history. While Cicero’s value as documentary evidence for the Hellenistic schools is unquestioned, Cicero: The Philosophy of a Roman Sceptic explores his writings as works of philosophy that do more than simply synthesize the thought of others, but instead offer a unique viewpoint of their own. In this volume Raphael Woolf describes and evaluates Cicero’s philosophical achievements, paying particular attention to his relation to those philosophers he draws upon in his works, his Romanizing of Greek philosophy, and his own sceptical and dialectical outlook. The volume aims, using the best tools of philosophical, philological and historical analysis, to do Cicero justice as a distinctive philosophical voice. Situating Cicero’s work in its historical and political context, this volume provides a detailed analysis of the thought of one of the finest orators and writers of the Roman period. Written in an accessible and engaging style, Cicero: The Philosophy of a Roman Sceptic is a key resource for those interested in Cicero’s role in shaping Classical philosophy. Raphael Woolf is Reader in Philosophy at King’s College London. His work focuses on ancient philosophy, and he has published on Plato, Aristotle and Hellenistic philosophy. Template: Royal A, Font: , Date: 28/01/2015; 3B2 version: 10.0.1465/W Unicode (Dec 22 2011) (APS_OT) Dir: //integrafs1/kcg/2-Pagination/TandF/CICERO_COR/ApplicationFiles/9781844658404_text.3d PHILOSOPHY IN THE ROMAN WORLD Forthcoming: Seneca R. -

1 / Swanson RESEARCH AREAS

Curriculum Vitae CARRIE E. SWANSON Assistant Professor Department of Philosophy | University of Iowa Room 256 | English-Philosophy Building Iowa City, IA 52240 Email: [email protected] Phone: (319)-335-5313 (work) (609) 865-8012 (home) EDUCATION: Reed College (B.A. Philosophy, 1991). Thesis: Plato’s Philebus. Supervisor: C.D.C. Reeve. Rutgers University, New Brunswick 2003-2011. Ph.D. Philosophy, May 2011. Dissertation: Socratic Dialectic and the Resolution of Fallacy in Plato’s Euthydemus. Committee: Alan Code, Robert Bolton, Jeff King (Rutgers), Benjamin Morison (Princeton). PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS: 2013 to present: Assistant Professor, Department of Philosophy, University of Iowa. 2011-2013: Ruth Norman Halls Postdoctoral Fellow in the History of Philosophy, Department of Philosophy, Indiana University. HONORS AND AWARDS: Rutgers Graduate School-New Brunswick Dissertation Teaching Award 2009-2010. Rutgers University Sellon Dissertation Fellowship 2008-2009. ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL MEMBERSHIPS: Chicago Area Consortium in Ancient Philosophy (2013-present). International Plato Society (2011-present). Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy (2010-present). American Philosophical Association (2008-present). Princeton University Reading Group in Ancient Philosophy (2001-2010). (Presented multiple times on the following Greek texts: Aristotle: Metaphysics Beta; Nicomachean Ethics 7; De Anima 1-2; De Motu Animalium. Plato: Theaetetus; Republic 6-7; Sophist; Timaeus. Sextus: Outlines III (on the good, bad, and indifferent, and the art of living); Epicurus: Letter to Herodotus. Regular faculty participants: John Cooper, Christian Wildberg, Hendrik Lorenz, Ben Morison, Alexander Nehamas. Past visiting participants: Michael Frede, Myles Burnyeat, Stephen Menn, Thomas Johansen, Raphael Woolf, Ursula Coope, Jonathan Beere). 1 / Swanson RESEARCH AREAS: Area of specialization: Ancient Philosophy.