The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec/Jan 2010

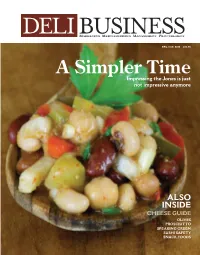

DELI BUSINESS MARKETING MERCHANDISING MANAGEMENT PROCUREMENT DEC./JAN. 2010 $14.95 A Simpler Time Impressing the Jones is just not impressive anymore ALSO INSIDE CHEESE GUIDE OLIVES PROSCIUTTO SPEAKING GREEN SUSHI SAFETY SNACK FOODS DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 COVER STORY CONTENTS DELI MEAT Ah, Prosciutto! ..........................................22 Any way you slice it, prosciutto is in demand FEATURES Snack Attack..............................................32 Consumers want affordable, healthful, cutting-edge snacks and appetizers 14 MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Creating An Olive Showcase ....................19 Time-tested merchandising techniques can boost the sales potential of deli olives 22 Green Merchandising ................................26 Despite a tough economy, consumers still want environmentally friendly products DELI BUSINESS (ISSN 1088-7059) is published by Phoenix Media Network, Inc., P.O. Box 810425, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0425 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to DELI BUSINESS, P.O. Box 810217, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0217 DEC./JAN. 2010 DELI BUSINESS 3 DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 CONTENTS COMMENTARIES EDITOR’S NOTE Good Food Desired In Bad Times ................8 PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS The Return of Cooking ..............................10 MARKETING PERSPECTIVE The New Frugality......................................53 IN EVERY ISSUE DELI WATCH ....................................................12 TECHNEWS ......................................................52 29 BLAST FROM THE PAST ........................................54 -

Gastronomieführer Meißen ( Pdf | 3,61

Gastronomieführer Dining guide 2020 – 2022 Wir bringen Sie auf den Geschmack! Willkommen in Meißen, einer Stadt voll von bewegter Geschichte, magischer Schönheit, Genuss und lebendiger Tradition. In Meißen genießen Sie mit allen Sinnen. Gemütliche Straßencafés und traditionelle Konditoreien, urige Gasthäuser und stilvolle Res- taurants oder typische Weinstuben und Besenwirtschaften laden zu kulinarischen Pausen ein oder lassen den Tag wundervoll aus- klingen. Dabei reicht das Angebot von internationaler Küche, über regiona- le Spezialitäten, Meißner Wein bis hin zum Bier der ältesten Privat- brauerei Sachsens. Eine Tausendjährige empfängt Sie mit all ihrem Charme und macht Geschmack auf mehr! Übersichts- karte auf S.28/29 Legende Barrierefrei* Spielecke/Spielplatz Accessible* Play area/playground Kinderfreundlich Terrasse/Biergarten Child-friendly Terrace/beer garden * Stufenloser Zugang, z. T. Behindertentoilette, bitte fragen Sie nach * Stepless access, disabled toilets available in some cases, please enquire We’ll tantalise your taste buds! Welcome to Meissen, a city packed full of rich history, magical beauty, enjoyment and vibrant traditions. It’s a place where you can indulge with all your senses. Cosy street cafés and historic patisseries, rustic pubs and stylish restaurants or typical wine bars and seasonal wine taverns are the perfect places for a culinary treat or to wind down at the end of the day. The options range from international cuisine, to regional speciali- ties and Meissen wine, to beer from Saxony’s oldest private brew- ery. This thousand-year-old dame will turn on her charm and have you salivating for more! Übersichts- Map on page e auf S.28/29 28/29 Parkmöglichkeiten Vegan Parking Vegan WLAN-Hotspot Glutenfrei WiFi hotspot Gluten-free Bio-Produkte Laktosefrei Organic products Lactose-free 1 Restaurants 1 Am Hundewinkel ......................................................................... -

New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm

http://nyti.ms/1nslqSQ HOME & GARDEN New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm JULY 23, 2014 In the Garden By MICHAEL TORTORELLO FALLS VILLAGE, Conn. — Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer! Come at daybreak — 6 o’clock sharp — to tramp through the dew and pray and sing in the misty fields. Let the fellowship program called Adamah feed your soul while you feed the soil. (In Hebrew, “Adamah†means soil, or earth.) Come be the vanguard of Jewish regeneration and ecological righteousness! Also, wear muck boots. There’s a lot of dew and chicken guano beneath the firmament. What is that you say? You’re praying for a few more hours of sleep in your cramped group house, down the road from the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center? After a month at Adamah, you’re exhausted from chasing stray goats and pounding 350 pounds of lacto-fermented curry kraut? Let’s try this again, then: Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer, because attendance is mandatory. “They definitely throw you all in,†said Tyler Dratch, a 22-year-old student at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s List College, in Manhattan. “It’s not like you do meditation, and if you like it, you can do it every day. You’re going to meditate every day, whether you like it or not.†As it happens, Mr. Dratch and the dozen other Adamahniks tramping through the dew on a recent weekday morning were also bushwhacking a trail in modern Jewish life. -

German Menu German Cuisine

GERMAN MENU GERMAN CUISINE German cuisine has evolved as a national cuisine through centuries of social and political change with variations from region to region. The southern regions of Germany, including Bavaria with vinegar and instead of capers, Marsh Marigold and neighbouring Swabia, share many dishes. buds soaked in brine were used. While cooking with Furthermore, across the border in Austria one will wine (as is typical in the wine growing regions of find many similar dishes. Franconia and Hesse) was known, the lack of good wine on the East German market reserved this for However, ingredients and dishes vary by province. special occasions. For these reasons Ragout fin There are many significant regional dishes that have (commonly known as Würzfleisch) became a highly become both national and regional. Many dishes sought after delicacy. that were once regional, however, have proliferated in different variations across the country into the Foreign Influences present day. With the influx of foreign workers after World War Pretzels are especially common in the South of II, many foreign dishes have been adopted into Germany. German regional cuisine can be divided German cuisine - Italian dishes like spaghetti and into many varieties such as Bavarian cuisine pizza have become a staple of the German diet. (Southern Germany), Thuringian (Central Germany), Turkish immigrants also have had a considerable Lower Saxon cuisine or those of Saxony Anhalt. influence on German eating habits; Döner kebab is Germany’s favourite fast food, selling twice as much The Eichstrich as the major burger chains put together (McDonald’s and Burger King being the only widespread burger All cold drinks in bars and restaurants are sold in chains in Germany). -

Read Book the Food of Taiwan Ebook Free Download

THE FOOD OF TAIWAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cathy Erway | 240 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780544303010 | English | Boston, United States The Food of Taiwan PDF Book Part travelogue and part cookbook, this book delves into the history of Taiwan and the author's own family history as well. French Food at Home. Categories: Side dish; Taiwanese; Vegan; Vegetarian Ingredients: light soy sauce; Chinese white rice wine; chayote shoots. Recently, deep-fried vegetarian rolls wrapped in tofu sheets have appeared in this section of the offering. Bowls of sweet or salty soy milk are classic Taiwanese breakfast fodder, accompanied by a feast of spongy, focaccia-like shao bing sesame sandwiches ; crispy dan bing egg crepes ; and long, golden- fried you tiao crullers. Your email address will not be published. Home 1 Books 2. The switch from real animals to noodles was made over a decade ago, we were told, to cut costs and reduce waste. For example, the San Bei Ji was so salty it was borderline inedible, while the Niu Rou Mian was far heavier on the soy sauce than any version I've had in Taiwan. Hardcover , pages. Little has changed over the years in terms of the nature of the ceremony and the kind of attire worn by the participants, but there have been some surprising innovations in terms of what foods are offered and how they are handled. Aside from one-off street stalls and full-blown restaurants, there are a few other unexpected spots for a great meal. I have to roll my eyes when she says that Taiwan is "diverse" even though it has a higher percentage of Han Chinese than mainland China does and is one of the most ethnically homogeneous states in the world. -

Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia As Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks

Teresa Smolińska Chair of Culture and Folklore Studies Faculty of Philology University of Opole Researchers of Culture Confronted with the “Treasures of Culinary Heritage” in Upper Silesia as Described in the Most Recent Cookbooks Abstract: Considering that in the last few years culinary matters have become a fashionable topic, the author is making a preliminary attempt at assessing many myths and authoritative opinions related to it. With respect to this aim, she has reviewed utilitarian literature, to which culinary handbooks certainly belong (“Con� cerning the studies of comestibles in culture”). In this context, she has singled out cookery books pertaining to only one region, Upper Silesia. This region has a complicated history, being an ethnic borderland, where after the 2nd World War, the local population of Silesians ��ac���������������������uired new neighbours����������������������� repatriates from the ����ast� ern Borderlands annexed by the Soviet Union, settlers from central and southern Poland, as well as former emigrants coming back from the West (“‘The treasures of culinary heritage’ in cookery books from Upper Silesia”). The author discusses several Silesian cookery books which focus only on the specificity of traditional Silesian cuisine, the Silesians’ curious conservatism and attachment to their regional tastes and culinary customs, their preference for some products and dislike of other ones. From the well�provided shelf of Silesian cookery books, she has singled out two recently published, unusual culinary handbooks by the Rev. Father Prof. Andrzej Hanich (Opolszczyzna w wielu smakach. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. 2200 wypróbowanych i polecanych przepisów na przysmaki kuchni domowej, Opole 2012; Smaki polskie i opolskie. Skarby dziedzictwa kulinarnego. -

The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book All Faculty Scholarship Chapters 9-2009 The irsF t Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2009). The irF st Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet. In Susan R. Friedland (Eds.), Vegetables (29–35). Totnes, Devon, England: Oxford Symposium/Prospect Books https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks/86 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala Throughout history vegetarian diets, variously defined, have been adopted as a matter of economic necessity or as a form of abstinence, to strengthen the soul by denying the body’s physical demands. In the Western tradition there have been many who avoided flesh out of ethical concern for the welfare of animals and this remains a strong impetus in contemporary culture. Yet today, we are fully aware scientifically that it is perfectly possible to enjoy health on a purely vegetarian diet. This knowledge stems largely from early research into the nature of proteins, and awareness, after Justus von Leibig’s research in the nineteenth century, that plants contain muscle-building compounds, if not a complete package of amino acids. -

The Olive and Imaginaries of the Mediterranean

History and Anthropology ISSN: 0275-7206 (Print) 1477-2612 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghan20 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley To cite this article: Anne Meneley (2020) The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean, History and Anthropology, 31:1, 66-83, DOI: 10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 Published online: 14 Nov 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 29 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghan20 HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY 2020, VOL. 31, NO. 1, 66–83 https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper explores how the olive tree and olive oil continue to seep Olive oil; Mediterranean; food into imaginaries of the Mediterranean. The olive tree, long lived and anthropology; circulations of durable, requires human intervention to be productive: it is commodities; imaginaries emblematic of the Mediterranean region and the longstanding human habitation of it. Long central to the religious imaginaries and practices of the monotheistic tradition and those which preceded it, olive oil has emerged, in recent decades, as the star of The Mediterranean Diet. This paper, inspired by anthropologists who follow the ‘thing’, also follows the advocates, both scientists and chefs, who tout the scientific research which underpins The Mediterranean Diet’s claims, which critics might consider part of contemporary ideologies of ‘healthism’ and ‘nutritionism’. -

The Agricultural and Food Heritage Evolution of Eating Habits and Taste Between Tradition and Innovation

ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE The agricultural and food heritage Evolution of eating habits and taste between tradition and innovation by Marta Lenzi expert on the history of gastronomy and customs The key facts in brief Today our meals begin with savory and end with sweet, we combine pasta with tomato sauce, we choose what and when to eat. But it was not always like this. Food, as an item of social and cultural identity, is characterized by choices and preferences that have changed over the centuries. Taste follows from flavor and is an individual sensation. But, we must also realize that it’s influenced by cultural, economic and social circumstances. At the root of the traditions there are gastronomic influences resulting from the meeting of different cultures, a continuous exchange between peoples. In recent decades, the globalized food model has been established, offering everything and more, at any time, even at the risk of losing our specialties and identity. Our agricultural and food heritage, combined with a greater awareness of the value of food, becomes the starting point for reassessing the local cuisine, understood as a combination of tradition, creativity and innovation. Consumers have realized that foods form a cumulation of history, rediscovering its roots, having a new interest in products and gastronomic specialties that are today better and more reliable thanks to innovations in the industry. 1 The agricultural and food heritage by Marta Lenzi ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE To better understand: a few basic concepts Garum: a type of fermented fish sauce typical of the Roman period, obtained from the intestines and other parts of fish waste, marinated in salt, mixed with spices, herbs, oil, vinegar, honey, wine, figs and dates. -

The Use of Food to Signify Class in the Comedies of Carlo Goldoni 1737-1762

ABSTRACT Title of Document: “THE SAUCE IS BETTER THAN THE FISH”: THE USE OF FOOD TO SIGNIFY CLASS IN THE COMEDIES OF CARLO GOLDONI 1737-1762. Margaret Anne Coyle, Ph.D, 2006 Directed By: Dr. Heather Nathans, Department of Theatre This dissertation explores the plays of Venetian Commedia del’Arte reformer- cum-playwright Carlo Goldoni, and documents how he manipulates consumption and material culture using fashionable food and dining styles to satirize class structures in eighteenth century Italy. Goldoni’s works exist in what I call the “consuming public” of eighteenth century Venice, documenting the theatrical, literary, and artistic production of the city as well as the trend towards Frenchified social production and foods in the stylish eating of the period. The construction of Venetian society in the middle of the eighteenth century was a specific and legally ordered cultural body, expressed through various extra-theatrical activities available during the period, such as gambling, carnival, and public entertainments. The theatrical conventions of the Venetian eighteenth century also explored nuances of class decorum, especially as they related to audience behavior and performance reception. This decorum extended to the eating styles for the wealthy developed in France during the late seventeenth century and spread to the remainder of Europe in the eighteenth century. Goldoni ‘s early plays from 1737 through 1752 are riffs on the traditional Commedia dell’Arte performances prevalent in the period. He used food in these early pieces to illustrate the traditional class and regional affiliations of the Commedia characters. Plays such as The Artful Widow, The Coffee House, and The Gentleman of Good Taste experimented with the use of historical foods styles that illustrate social placement and hint at further character development. -

Discovery Map Freiberg

MINERALOGICAL CITY AND SILVER MINE CATHEDRAL OF TERRA MINERALIA COLLECTION GERMANY MINING MUSEUM “REICHE ZECHE” ST. MARY The entire world of minerals. at Krügerhaus One of Saxony’s oldest With over 800 years of tradition Heavenly organ sounds and museums with an impressive and 1000 ore veins, the Freiberg unique artistic treasures late Gothic ambience. mining area is the biggest and from the past 800 years. city silver the Discover oldest in Saxony. FREIBERG DISCOVERY MAP DISCOVERY With 3,500 minerals, Minerals from German sites Various presentations provide “Underground Freiberg” The most important Baroque TOUR CITY AND MAP CITY INCL. gemstones and meteorites, Opening Times have been on permanent Opening Times an introduction to the world of Opening Times stretches over an area of 5 x 6 Tours* organ in the world, the 300 Opening Times terra mineralia is a Mon – Fri: 10 am – 5 pm exhibition since October 2012 Mon – Fri: 10 am – 4 pm Freiberg’s famous ore mining Tue – Sun: 10 am – 5 pm kilometres beneath the silver without reservation: year old and thereby oldest November to April: permanent exhibition of the Sat, Sun, Hollidays: 10 am – 6 pm in the Mineralogical Collection Sat, Sun, Hollidays: 10 am – 6 pm and present the history of the Admission until 4.30 pm city and beyond. Travel like a Wed – Fr: surviving organ of Gottfried Mo – Sat: 11 am – 4 pm TU Bergakademie Freiberg, Germany in Krügerhaus, right silver city: focusing mainly miner in a cage conveyor 150 m 10.30 am Mining tour (1.5 h) Silbermann, can be heard in Sun, relig. -

Read Travel Planning Guide

GCCL TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE Romance of the Rhine & Mosel 2021 Learn how to personalize your experience on this vacation Grand Circle Cruise Line® The Leader in River Cruising Worldwide 1 Grand Circle Cruise Line ® 347 Congress Street, Boston, MA 02210 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. Soon, you’ll once again be discovering the places you’ve dreamed of. In the meantime, the enclosed Grand Circle Cruise Line Travel Planning Guide should help you keep those dreams vividly alive. Before you start dreaming, please let me reassure you that your health and safety is our number one priority. As such, we’re requiring that all Grand Circle Cruise Line travelers, ship crew, Program Directors, and coach drivers must be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 at least 14 days prior to departure. Our new, updated health and safety protocols are described inside. The journey you’ve expressed interest in, Romance of the Rhine & Mosel River Cruise, will be an excellent way to resume your discoveries. It takes you into the true heart of Europe, thanks to our groups of 38-45 travelers. Plus, our European Program Director will reveal their country’s secret treasures as only an insider can. You can also rely on the seasoned team at our regional office in Bratislava, who are ready to help 24/7 in case any unexpected circumstances arise. Throughout your explorations, you’ll meet local people and gain an intimate understanding of the regional culture. Get a glimpse of everyday German life when you join a family for a Home-Hosted Visit in Speyer, enjoying an afternoon of homemade treats and friendly conversation; and learn about the love and pride poured into Germany’s fine vintages during a behind-the-scenes tour of a winery in Bernkastel, followed by a tasting.