Heidi Krahling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec/Jan 2010

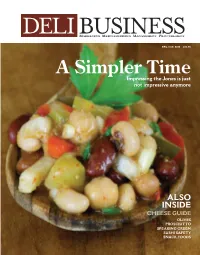

DELI BUSINESS MARKETING MERCHANDISING MANAGEMENT PROCUREMENT DEC./JAN. 2010 $14.95 A Simpler Time Impressing the Jones is just not impressive anymore ALSO INSIDE CHEESE GUIDE OLIVES PROSCIUTTO SPEAKING GREEN SUSHI SAFETY SNACK FOODS DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 COVER STORY CONTENTS DELI MEAT Ah, Prosciutto! ..........................................22 Any way you slice it, prosciutto is in demand FEATURES Snack Attack..............................................32 Consumers want affordable, healthful, cutting-edge snacks and appetizers 14 MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Creating An Olive Showcase ....................19 Time-tested merchandising techniques can boost the sales potential of deli olives 22 Green Merchandising ................................26 Despite a tough economy, consumers still want environmentally friendly products DELI BUSINESS (ISSN 1088-7059) is published by Phoenix Media Network, Inc., P.O. Box 810425, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0425 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to DELI BUSINESS, P.O. Box 810217, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0217 DEC./JAN. 2010 DELI BUSINESS 3 DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 CONTENTS COMMENTARIES EDITOR’S NOTE Good Food Desired In Bad Times ................8 PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS The Return of Cooking ..............................10 MARKETING PERSPECTIVE The New Frugality......................................53 IN EVERY ISSUE DELI WATCH ....................................................12 TECHNEWS ......................................................52 29 BLAST FROM THE PAST ........................................54 -

Catering Menu

Private events and catering Welcome to Soul Taco, a place where food is fun, playful and most importantly, FLAVORFUL. Soul Taco combines Southern cooking, California Cuisine and everyone’s favorite; TACOS ! ! Let our innovative yet familiar flavors dance across the palates of you & your guests and impress them by having the trendiest spot in town cater your event. We offer pickup, drop-off and restaurant buyout options to fit any occasion. E-mail all inquiries to: [email protected] PICK-UP/DROP OFF ADD SOME SOUL TO YOUR LIFE - $12 PP ADD ADDITIONAL TACOS + $2 .50 PP Choose 3 Buttermilk Battered Fried Chicken Roasted Sweet Potato and Black-Eyed Pea (V) Fried chicken, Pickled red onions, avocado, Roasted Sweet Potato and Black-Eyed Peas, Pickled Chipotle BBQ Crema, Agave Hot Sauce, Flour red onions, avocado, cilantro crema, cotija cheese, tortilla crispy yucca, Corn Tortilla Cornmeal Crusted Catfish Cauliflower Gringo (V) Cornmeal crusted catfish, tomatillo salsa, red Riced Cauliflower “beef”, Pico de Gallo, Chihuahua cabbage slaw, Hot sauce aioli, Corn Tortilla cheese cookie, Jalapeno-Lime ranch, Hard Shell Blackened Catfish Corn Tortilla Blackened fish, Black eyed pea & Corn succotash, Chicken Fried Carne Asada cilantro crema, fried yucca, Corn Tortilla Chicken fried steak, Roasted red pepper, Pico de *Oxtail Taco Gallo, Avocado, Hot sauce aioli, Flour tortilla Root Beer braised oxtail, Pineapple-Jalapeno *Low Country Camarones salsa, Chicharrones, Agave hot sauce, Corn Shrimp, Chorizo, Potato salsa, Elote salad, Old Bay Tortilla crema -

Chef Joe Randall Has Helped Define Southern Cooking for 50 Years. 8/3/17, 9�52 AM Dinner with the Dean of Southern Cuisine

Chef Joe Randall has helped define Southern cooking for 50 years. 8/3/17, 9)52 AM Dinner with the Dean of Southern Cuisine If you take Chef Joe Randall’s cooking class in Savannah, Georgia, come hungry and wear loose clothes. This is not one of those cooking demonstrations where everyone gets a morsel to taste; it’s a full four-course meal like you only get in the Low Country. On the 15th anniversary of his Savannah cooking school—which also marks his 52 years in the hospitality and food industry—Randall, 69, served shrimp and grits, fried green tomatoes on a bed of Bibb lettuce, okra and butter beans, Gullah crab rice and pan-fried snapper, followed by peach cobbler with ice cream. No one left hungry and everyone left entertained—including the chef. “You asked me how I keep going at my age,” he says, “and my wife sure wants me to retire. But when you’re having this much fun, it’s hard to walk away. Besides, the boss ain’t mean—since the boss is me.” Randall started cooking as a young man in the Air Force. An uncle who owned a restaurant in his native Pittsburgh “gave me a tease for the business,” he says. “I was free labor but it was a joy.” He went on to apprentice under two award-winning chefs at different hotels in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and then began the peripatetic life of a working chef with a passion for different cuisines. He worked on both coasts and met his wife, Barbara, while working in Sacramento. -

New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm

http://nyti.ms/1nslqSQ HOME & GARDEN New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm JULY 23, 2014 In the Garden By MICHAEL TORTORELLO FALLS VILLAGE, Conn. — Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer! Come at daybreak — 6 o’clock sharp — to tramp through the dew and pray and sing in the misty fields. Let the fellowship program called Adamah feed your soul while you feed the soil. (In Hebrew, “Adamah†means soil, or earth.) Come be the vanguard of Jewish regeneration and ecological righteousness! Also, wear muck boots. There’s a lot of dew and chicken guano beneath the firmament. What is that you say? You’re praying for a few more hours of sleep in your cramped group house, down the road from the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center? After a month at Adamah, you’re exhausted from chasing stray goats and pounding 350 pounds of lacto-fermented curry kraut? Let’s try this again, then: Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer, because attendance is mandatory. “They definitely throw you all in,†said Tyler Dratch, a 22-year-old student at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s List College, in Manhattan. “It’s not like you do meditation, and if you like it, you can do it every day. You’re going to meditate every day, whether you like it or not.†As it happens, Mr. Dratch and the dozen other Adamahniks tramping through the dew on a recent weekday morning were also bushwhacking a trail in modern Jewish life. -

Read Book the Food of Taiwan Ebook Free Download

THE FOOD OF TAIWAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cathy Erway | 240 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780544303010 | English | Boston, United States The Food of Taiwan PDF Book Part travelogue and part cookbook, this book delves into the history of Taiwan and the author's own family history as well. French Food at Home. Categories: Side dish; Taiwanese; Vegan; Vegetarian Ingredients: light soy sauce; Chinese white rice wine; chayote shoots. Recently, deep-fried vegetarian rolls wrapped in tofu sheets have appeared in this section of the offering. Bowls of sweet or salty soy milk are classic Taiwanese breakfast fodder, accompanied by a feast of spongy, focaccia-like shao bing sesame sandwiches ; crispy dan bing egg crepes ; and long, golden- fried you tiao crullers. Your email address will not be published. Home 1 Books 2. The switch from real animals to noodles was made over a decade ago, we were told, to cut costs and reduce waste. For example, the San Bei Ji was so salty it was borderline inedible, while the Niu Rou Mian was far heavier on the soy sauce than any version I've had in Taiwan. Hardcover , pages. Little has changed over the years in terms of the nature of the ceremony and the kind of attire worn by the participants, but there have been some surprising innovations in terms of what foods are offered and how they are handled. Aside from one-off street stalls and full-blown restaurants, there are a few other unexpected spots for a great meal. I have to roll my eyes when she says that Taiwan is "diverse" even though it has a higher percentage of Han Chinese than mainland China does and is one of the most ethnically homogeneous states in the world. -

The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book All Faculty Scholarship Chapters 9-2009 The irsF t Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2009). The irF st Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet. In Susan R. Friedland (Eds.), Vegetables (29–35). Totnes, Devon, England: Oxford Symposium/Prospect Books https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks/86 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala Throughout history vegetarian diets, variously defined, have been adopted as a matter of economic necessity or as a form of abstinence, to strengthen the soul by denying the body’s physical demands. In the Western tradition there have been many who avoided flesh out of ethical concern for the welfare of animals and this remains a strong impetus in contemporary culture. Yet today, we are fully aware scientifically that it is perfectly possible to enjoy health on a purely vegetarian diet. This knowledge stems largely from early research into the nature of proteins, and awareness, after Justus von Leibig’s research in the nineteenth century, that plants contain muscle-building compounds, if not a complete package of amino acids. -

California Cuisine

SUMMER 2016 explore California cuisine Discover Central Texas Barbecue Brisket corporate training chefs enjoy a work-life balance sizzle The American Culinary Federation features Quarterly for Students of Cooking NEXT Publisher 18 Consider the Environment IssUE American Culinary Federation, Inc. Environmental responsibility extends to a • sustainable food Editor-in-Chief restaurant’s water and energy conservation. Learn • root vegetables Jody Shee helpful measures that also save money. • home food delivery chef Senior Editor 24 Southern Cuisine Kay Orde The popular regional fare leaves room for local Graphic Designer interpretations for an eclectic cross-section of eateries and David Ristau consumer preferences. Contributing Editors Rob Benes 30 Train Others for Success Suzanne Hall Ethel Hammer Learn why some industry veterans love Amelia Levin the job of corporate training chef, where they work on restaurant openings and Direct all editorial, advertising and subscription inquiries to: then move on to the next project. 18 24 30 American Culinary Federation, Inc. 180 Center Place Way St. Augustine, FL 32095 (800) 624-9458 [email protected] departments Subscribe to Sizzle: 4 President’s Message www.acfchefs.org/sizzle ACF president Thomas Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC, sees a bright culinary future. For information about ACF certification and membership, 6 Amuse-Bouche go to www.acfchefs.org. Student news, opportunities and more. 10 Slice of Life Anica Hosticka walks us through a memorable day in her apprenticeship program at facebook.com/ACFChefs @acfchefs the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana. 12 Classical V. Modern Sizzle: The American Culinary Federation Quarterly Thomas Meyer and Nate Marsh of Kendall College, Chicago, demonstrate two ways for Students of Cooking (ISSN 1548-1441), Summer Volume 13, Number 2, is owned by the of making Central Texas barbecue brisket and sides. -

WINTER 2020 FOOD PEOPLE BELLYING up Cater to More Than the Bros at the Bar

FOOD FANATICS FOOD FOOD PEOPLE MONEY & SENSE PLUS Peru Now Bellying Up Less is More Critic’s Choice Charting a global course, More than bros at the bar, A money-saving, food waste Words to heed, page 16 page 49 checklist, page 66 page 54 Sharing the Love of Food—Inspiring Business Success ROLL SOUTH WINTER 2020 ROLL SOUTH GLOBAL TAKES LEAD THE WAY FOOD PEOPLE BELLYING UP Cater to more than the bros at the bar. 49 SPEAK EASY Los Angeles Times restaurant critic Winter 2020 Bill Addison on the most exciting USFoods.com/foodfanatics dining city in America. 54 ROAD TRIP! Trek through the Bourbon Trail. 58 Small business is no small task. MONEY & SENSE So Progressive offers commercial auto and business NOW THAT’S EATERTAINMENT! insurance that makes protecting yours no big deal. When diners want more than each other’s company. Local Agent | ProgressiveCommercial.com ON THE COVER 61 Mexican influences reach the South LESS IS MORE when sweet potatoes When it comes to food waste, and masa come together for collard it pays to be scrappy. green wrapped 66 tamales. Get the recipe on page 38. IN EVERY ISSUE TREND TRACKER What’s on the radar, at high alert or fading out? 46 FEED THE STAFF Revised tipping and service fee models address wage disparities. FOOD 52 DROP MORE ACID IHELP Housemade vinegars cut waste Text services provide diners and control costs. another way to order delivery. 4 69 PERU NOW PR MACHINE Peruvian cuisine charts a How to tranquilize the online trolls. multicultural course. -

The Olive and Imaginaries of the Mediterranean

History and Anthropology ISSN: 0275-7206 (Print) 1477-2612 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghan20 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley To cite this article: Anne Meneley (2020) The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean, History and Anthropology, 31:1, 66-83, DOI: 10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 Published online: 14 Nov 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 29 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghan20 HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY 2020, VOL. 31, NO. 1, 66–83 https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper explores how the olive tree and olive oil continue to seep Olive oil; Mediterranean; food into imaginaries of the Mediterranean. The olive tree, long lived and anthropology; circulations of durable, requires human intervention to be productive: it is commodities; imaginaries emblematic of the Mediterranean region and the longstanding human habitation of it. Long central to the religious imaginaries and practices of the monotheistic tradition and those which preceded it, olive oil has emerged, in recent decades, as the star of The Mediterranean Diet. This paper, inspired by anthropologists who follow the ‘thing’, also follows the advocates, both scientists and chefs, who tout the scientific research which underpins The Mediterranean Diet’s claims, which critics might consider part of contemporary ideologies of ‘healthism’ and ‘nutritionism’. -

The Agricultural and Food Heritage Evolution of Eating Habits and Taste Between Tradition and Innovation

ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE The agricultural and food heritage Evolution of eating habits and taste between tradition and innovation by Marta Lenzi expert on the history of gastronomy and customs The key facts in brief Today our meals begin with savory and end with sweet, we combine pasta with tomato sauce, we choose what and when to eat. But it was not always like this. Food, as an item of social and cultural identity, is characterized by choices and preferences that have changed over the centuries. Taste follows from flavor and is an individual sensation. But, we must also realize that it’s influenced by cultural, economic and social circumstances. At the root of the traditions there are gastronomic influences resulting from the meeting of different cultures, a continuous exchange between peoples. In recent decades, the globalized food model has been established, offering everything and more, at any time, even at the risk of losing our specialties and identity. Our agricultural and food heritage, combined with a greater awareness of the value of food, becomes the starting point for reassessing the local cuisine, understood as a combination of tradition, creativity and innovation. Consumers have realized that foods form a cumulation of history, rediscovering its roots, having a new interest in products and gastronomic specialties that are today better and more reliable thanks to innovations in the industry. 1 The agricultural and food heritage by Marta Lenzi ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE To better understand: a few basic concepts Garum: a type of fermented fish sauce typical of the Roman period, obtained from the intestines and other parts of fish waste, marinated in salt, mixed with spices, herbs, oil, vinegar, honey, wine, figs and dates. -

Beyond Grits 16-17

LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY DINING GUIDE WELCOME WE’RE SO GLAD YOU’RE HERE Be part of the culinary revolution that is sweeping through Lexington! Exciting collaborations between local farms, chefs, restaurants and entrepreneurs have paved the way for a vibrant, critically-acclaimed dining scene that is garnering attention from both local and national audiences. In fact, Chef Mark Jensen’s new restaurant, Middle Fork Kitchen Bar (cover) was recently named one of the “100 Hottest Restaurants in America for 2016” by Open Table. Whether you’re in the mood for farm-to-table foodie freshness or an interesting twist on a Southern classic, you’ll find a place to satisfy any craving in town. Everything you need to know about Lexington’s thriving dining scene is right here in this guide. So go ahead — 2 / BEYOND GRITS 2016-17 – The Merrick Inn LEXINGTON DINING GUIDE / 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 16 26 NEW LOCAL FOODIE The hottest additions LANDMARKS APPROVED to our ever-growing Essential stops and local Fresh, local and creative dining scene. Lexington favorites, both dishes – whether you’re under-the-radar and a culinary connoisseur or world-famous. just a lover of great food. 34 40 48 DATE NIGHT CASUAL PUB FOOD White tablecloths, Relaxed atmospheres, Hearty burgers, heaping sophistication and warm uncommon hospitality nachos, chicken wings… ambiance for a romantic and dishes that will you know, things that go night out. please any palate. great with beer. 4 / BEYOND GRITS 2016-17 54 62 66 PORCHES BREAKFAST & SMOKED MEATS & PATIOS BRUNCH & BBQ Nothing goes better with Start your day off right For fans of the slow-roasted, delicious entrees like a with eggs, bacon and the hickory-smoked and the little fresh air and a view. -

CALIFORNIA-STYLE WINE COUNTRY RESTAURANTS & FARMERS’ MARKETS a Regional Focus on Enjoying the Artisan Food Trend with Local California Wines

Contact: Communications Dept. Wine Institute of California [email protected] CALIFORNIA-STYLE WINE COUNTRY RESTAURANTS & FARMERS’ MARKETS A Regional Focus on Enjoying the Artisan Food Trend with Local California Wines The popularity of California wine, fresh produce and regional cuisine continues to expand worldwide. For travelers to the state, one of the best ways to discover what’s new in fresh seasonal cooking and dining is to visit California’s wine country. Local restaurants focus on pairing regional wines with natural, farm-grown ingredients, often sourced from community farmers’ markets. These markets reflect the abundance of produce available in the state, as California is America’s top agricultural state, producing 400 plant and animal commodities. There are more than 400 certified farmers’ markets throughout California, many of them in the state’s wine regions. A complete listing is available at http://www.cafarmersmarkets.com. Mirroring the growth in California wineries, California farmers’ markets have continued to rise in popularity over the past three decades. Professional chefs shop alongside domestic consumers, looking for field-ripened fruits and vegetables, fragrant flowers, fresh fish, artisan breads and pastries, plus delicacies such as local olive oils and cheeses. Beginning in 2000, California wine can now be sold at qualified California Certified Farmers’ Markets. Restaurants and consumers alike are aware that more flavorful dishes can be created with heirloom vegetables and products, grown, raised or harvested with the same care that is put into their preparation. Food from local sources also travels from the farm to the plate in a timely manner. The freshness of the ingredients becomes part of the feature of the dish and supports the sustainable concept of “green dining” in that less fossil fuel is used to transport products from the farm to the kitchen.