The Olive and Imaginaries of the Mediterranean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scents and Flavours

Typical products Boccadasse - Genoa Agenzia Regionale per la Promozione Turistica “in Liguria” [email protected] www.turismoinliguria.it Seaside emotions Art Settings www.turismoinliguria.it History Trail Scents and flavours Sports itineraries A sea of gardens From the Woods, the Garden, and the Sea - a Taste of Ligurian Gastronomy - Shades of Flavours from Green to Blue. Publishing Info Publishing Project and All Rights reserved to Agenzia Regionale per la Promozione Turistica “in Liguria”. Images: Archive Agenzia “in Liguria”, and “Regione Liguria” from “Prodotti di Liguria Atlante Regionale dei prodotti tradizionali” - except for page 3-14-15-16-17-18-19-20-21-22 Slow Food Copyright. Graphic Project by: Adam Integrated Communications - Turin - Printed in 2008 - Liability Notice: notwithstanding the careful control checks Agenzia “in Liguria” is Farinata not liable for the reported content and information. www.turismoinliguria.it Scents and Tastes. In all Italian regions traditional recipes originate from the produce of the land. In Liguria the best ingredients are closely linked to sunny crops and terraces plummeting into the sea, to mountains, sandy and rocky beaches, valleys, and country plains. In this varied land fine cuisine flavours are enriched by genuine and simple products, this is why the Ligurian tradition for gourmet food and wine is an enchanting surprise to discover along the journey. Cicciarelli of Noli www.turismoinliguria.it Gallinella 3 Extra Virgin Olive Oil. This magic fluid, with a unique consistency, is the olive groves nectar and the ingredient for Mediterranean potions. The Extra Virgin Olive Oil of the Italian Riviera now has a millenary tradition. -

Olive Oil Award Winners

Olive Oil Award Winners CALIFORNIA STATE FAIR 2020 COMMERCIAL OLIVE OIL COMPETITION hile the California State Fair team had he California State Fair Commercial Extra Virgin Olive remained hopeful for a wonderful 2020 Oil Competition features two shows: Extra Virgin Olive WCalifornia State Fair & Food Festival, we TOil and Flavored Olive Oil. The Extra Virgin Olive Oil were faced with a world-wide pandemic none Show has divisions for varying intensities of single varieties of us could have ever imagined. However, at the and blends of olive oil, and classes in varietals of olives. beginning of the year, we were able to accept The Flavored Olive Oil Show has divisions in co-milled and entries and judge the California State Fair Olive infused olive oil, and classes for flavor varieties. Oil Competition for 2020. Three special awards honor olive oil producers of each This brochure is one way we are highlighting and production level: Best of California Extra Virgin Olive Oil honoring those who won Double Gold, Gold and by a Large Producer (over 5,000 gallons), an Artisan the highest honors in this year’s competition. Producer (500-5,000 gallons), and a Microproducer (less than 500 gallons). California’s extra virgin olive oil business is flourishing. The fall 2019 harvest was estimated to have produced 4 million gallons of extra virgin olive oil. As of Across 8 divisions and 14 different classes, two Best of January 2019, over 41,000 acres of olive groves were in production in California, Show Golden Bear trophies are awarded each year, one for specifically for olive oil. -

Dec/Jan 2010

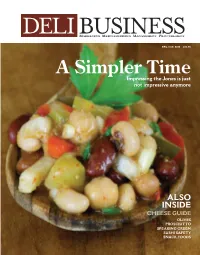

DELI BUSINESS MARKETING MERCHANDISING MANAGEMENT PROCUREMENT DEC./JAN. 2010 $14.95 A Simpler Time Impressing the Jones is just not impressive anymore ALSO INSIDE CHEESE GUIDE OLIVES PROSCIUTTO SPEAKING GREEN SUSHI SAFETY SNACK FOODS DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 COVER STORY CONTENTS DELI MEAT Ah, Prosciutto! ..........................................22 Any way you slice it, prosciutto is in demand FEATURES Snack Attack..............................................32 Consumers want affordable, healthful, cutting-edge snacks and appetizers 14 MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Creating An Olive Showcase ....................19 Time-tested merchandising techniques can boost the sales potential of deli olives 22 Green Merchandising ................................26 Despite a tough economy, consumers still want environmentally friendly products DELI BUSINESS (ISSN 1088-7059) is published by Phoenix Media Network, Inc., P.O. Box 810425, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0425 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to DELI BUSINESS, P.O. Box 810217, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0217 DEC./JAN. 2010 DELI BUSINESS 3 DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 CONTENTS COMMENTARIES EDITOR’S NOTE Good Food Desired In Bad Times ................8 PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS The Return of Cooking ..............................10 MARKETING PERSPECTIVE The New Frugality......................................53 IN EVERY ISSUE DELI WATCH ....................................................12 TECHNEWS ......................................................52 29 BLAST FROM THE PAST ........................................54 -

Divina Catalog Edit 2021.Pdf

Buckhead is proud to present the delicious line of Divina brand antipasti. Divina olives and antipasti represent the core values of authentic taste, traceability and superb quality. Sourced directly from growers across the Mediterranean, Divina’s olive varieties such as the Greek Kalamata, Italian Castelvetrano, and Mt. Athos Green are harvested and cured according to centuries-old methods. Using a 3rd-Party HACCP process, the commitment to integrity and quality above all is present in the delicate taste of each Divina olive. Divina’s antipasti selection reflects the vibrant colors and flavors of tables from around the Mediterranean and across the world. From their tender dolmas, to award winning roasted red and yellow peppers, every Divina antipasti is made with the finest ingredients and utmost care. Capers Nonpareil Fancy An essence of sea salt, a crisp, popping texture and floral flavor make Divina nonpareil fancy capers a unique ingredient. Non-GMO #20064, 6132oz Jars Curried Pickled Cauliflower Delightfully crunchy florets of pickled cauliflower filled with sweet and aromatic curry flavor. Crisp and bright pepper strips and black peppercorn balance the flavorful brine while adding visual appeal. #20852, 6/3.1 lb. Tin Cornichons Always fresh packed, DIVINA cornichons (French for gherkins) are made according to a traditional French recipe using the finest gherkins, vinegar and spices. They are bright, crunchy and delicious! The classic accompaniment to pate or as an essential ingredient in salad sandwiches (such as tuna, chicken ,or egg salad.) #20859, 3/4.7 lb. Cans DIVINA Fig Spread DIVINA Sour Cherry Spread Crafted from Aegean Figs, Divina Fig Spread is deeply Divina Sour Cherry Spread has a bold, fruit-forward flavor fruity and complex with notes of caramel and honey. -

2213 South Shore Center • Alameda, Ca 94501 • Trabocco.Com • Tel 510 521 1152

Antipasti Stuzzichini Polipo e Patate 14 Olive e Mandorle 8 Grilled octopus, potato, celery, red onion, lemon, olive oil Olives, almonds, ricotta salata Calamari Fritti 13 Pancia di Maiale 10 Breaded and fried calamari, spicy tomato sauce Braised pork belly, lentil faro pilaf Carpaccio 12 Baccala e Peperoni 10 Raw, grass-fed beef tenderloin, lemon, olive oil, shaved Roasted salt-cod marinated with roasted bell peppers, parmesan, arugula crispy polenta Burrata Con Prosciutto 14 Arrosticini 11 Di Stefano Burrata, prosciutto, grissini Grilled lamb-skewers, grill-toasted bread Crudo in Due 12 Saffron and lemon marinated raw fresh ahi-tuna, crispy capers, mint, and spicy ahi-tuna tartar Pizzeria Paste e Risotto Margherita 15 Chitarrine al Cacao* 18 Tomato sauce, basil, fior di latte House-made pasta with cocoa powder, rabbit ragú Mezzo e Mezzo 16 Maccheroni alla Pecorara* 15 Half calzone, half pizza with tomato, fior di latte, basil, Fresh tomato sauce, ricotta, eggplant ricotta, mushroom Fettuccine Bolognese* 17 Ortolano 16 House-made fettuccine pasta with meat ragú Zucchini, eggplant, artichokes, mushrooms, tomato Ravioli con Coda 18 sauce, fior di latte House-made pasta stuffed with braised oxtail, au jus, Cristina 17 pecorino pepato Mushrooms, fior di latte, arugula, prosciutto, shaved Agnolotti di Zucca 16 parmesan, truffle olive oil House-made pasta filled with butternut squash, Rapini e Salsiccia 16 walnuts, brown butter sage sauce, parmesan Spicy sausage, broccoli rabe, tomato sauce, fior di latte over fresh tomato sauce Del Salumiere 16 Spaghetti del Trabocco* 20 Tomato sauce, fior di latte, assorted Italian cured meats Baby octopus and tomato ragú with shrimp, scallops, clams, mussels Add-on’s Gnocchi all' Abbruzzese 16 Anchovies 3. -

New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm

http://nyti.ms/1nslqSQ HOME & GARDEN New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm JULY 23, 2014 In the Garden By MICHAEL TORTORELLO FALLS VILLAGE, Conn. — Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer! Come at daybreak — 6 o’clock sharp — to tramp through the dew and pray and sing in the misty fields. Let the fellowship program called Adamah feed your soul while you feed the soil. (In Hebrew, “Adamah†means soil, or earth.) Come be the vanguard of Jewish regeneration and ecological righteousness! Also, wear muck boots. There’s a lot of dew and chicken guano beneath the firmament. What is that you say? You’re praying for a few more hours of sleep in your cramped group house, down the road from the Isabella Freedman Jewish Retreat Center? After a month at Adamah, you’re exhausted from chasing stray goats and pounding 350 pounds of lacto-fermented curry kraut? Let’s try this again, then: Come seek enlightenment in the chicken yard, young Jewish farmer, because attendance is mandatory. “They definitely throw you all in,†said Tyler Dratch, a 22-year-old student at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s List College, in Manhattan. “It’s not like you do meditation, and if you like it, you can do it every day. You’re going to meditate every day, whether you like it or not.†As it happens, Mr. Dratch and the dozen other Adamahniks tramping through the dew on a recent weekday morning were also bushwhacking a trail in modern Jewish life. -

Recipe for Koshari

Recipe for Koshari What is Koshari? Koshari or koshary is considered the national dish of Egypt and is made with a mixture of ingredients including brown lintels, pasta, chickpeas, and rice. It is a true comfort food that is reasonably priced and considered vegan. Koshari can be found being sold in streetcars with colored glass, and is so popular that some restaurants sell only koshari! Koshari is recognized as the food of the revolution! Kosharia is Bengali in origin, and may have come to Egypt in the 1880’s with British troops. In its origins, it may have been made from a mixture of rice and yellow lentils called kichdi or kichri, and served for breakfast. However, now it is now considered a common Egyptian dish, served with tomato sauce and salad. Now it’s your turn to make your koshari! Follow the steps below for cooking each part of koshari and then assemble. Top with tomato sauce and fried onions to finish! Ingredients to Make Koshari: When making koshari, it is common to use whatever ingredients you have at home-adjust as needed! ● olive oil or ghee ● 5 or 6 tomatoes of any kind (or 28 oz can of Italian crushed tomatoes) ● 6 to 8 onions sliced for fried onions (optional to purchase a can of fried onions instead) ● 8 oz brown lentils ● 6 oz medium-grain rice ● 6 oz vermicelli ● 9 oz elbow pasta ● 15 oz can of chickpeas/garbanzo beans (optional to use/cook dried garbanzo beans) ● salt and pepper ● garlic ● white wine vinegar ● cumin ● hot chili powder ● tomato paste ● 1 sweet green pepper ● water Follow steps below to prepare each element of koshari. -

Read Book the Food of Taiwan Ebook Free Download

THE FOOD OF TAIWAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cathy Erway | 240 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780544303010 | English | Boston, United States The Food of Taiwan PDF Book Part travelogue and part cookbook, this book delves into the history of Taiwan and the author's own family history as well. French Food at Home. Categories: Side dish; Taiwanese; Vegan; Vegetarian Ingredients: light soy sauce; Chinese white rice wine; chayote shoots. Recently, deep-fried vegetarian rolls wrapped in tofu sheets have appeared in this section of the offering. Bowls of sweet or salty soy milk are classic Taiwanese breakfast fodder, accompanied by a feast of spongy, focaccia-like shao bing sesame sandwiches ; crispy dan bing egg crepes ; and long, golden- fried you tiao crullers. Your email address will not be published. Home 1 Books 2. The switch from real animals to noodles was made over a decade ago, we were told, to cut costs and reduce waste. For example, the San Bei Ji was so salty it was borderline inedible, while the Niu Rou Mian was far heavier on the soy sauce than any version I've had in Taiwan. Hardcover , pages. Little has changed over the years in terms of the nature of the ceremony and the kind of attire worn by the participants, but there have been some surprising innovations in terms of what foods are offered and how they are handled. Aside from one-off street stalls and full-blown restaurants, there are a few other unexpected spots for a great meal. I have to roll my eyes when she says that Taiwan is "diverse" even though it has a higher percentage of Han Chinese than mainland China does and is one of the most ethnically homogeneous states in the world. -

Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing

–8– “Bread from Heaven, Bread from the Earth”: Recent Trends in Jewish Food History Writing Jonathan Brumberg-Kraus Over the last thirty years, Jewish studies scholars have turned increasing attention to food and meals in Jewish culture. These studies fall more or less into two different camps: (1) text-centered studies that focus on the authors’ idealized, often prescrip- tive construction of the meaning of food and Jewish meals, such as biblical and postbiblical dietary rules, the Passover Seder, or food in Jewish mysticism—“bread from heaven”—and (2) studies of the “performance” of Jewish meals, particularly in the modern period, which often focus on regional variations, acculturation, and assimilation—“bread from the earth.”1 This breakdown represents a more general methodological split that often divides Jewish studies departments into two camps, the text scholars and the sociologists. However, there is a growing effort to bridge that gap, particularly in the most recent studies of Jewish food and meals.2 The major insight of all of these studies is the persistent connection between eating and Jewish identity in all its various manifestations. Jews are what they eat. While recent Jewish food scholarship frequently draws on anthropological, so- ciological, and cultural historical studies of food,3 Jewish food scholars’ conver- sations with general food studies have been somewhat one-sided. Several factors account for this. First, a disproportionate number of Jewish food scholars (compared to other food historians) have backgrounds in the modern academic study of religion or rabbinical training, which affects the focus and agenda of Jewish food history. At the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, my background in religious studies makes me an anomaly. -

The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book All Faculty Scholarship Chapters 9-2009 The irsF t Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2009). The irF st Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet. In Susan R. Friedland (Eds.), Vegetables (29–35). Totnes, Devon, England: Oxford Symposium/Prospect Books https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks/86 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala Throughout history vegetarian diets, variously defined, have been adopted as a matter of economic necessity or as a form of abstinence, to strengthen the soul by denying the body’s physical demands. In the Western tradition there have been many who avoided flesh out of ethical concern for the welfare of animals and this remains a strong impetus in contemporary culture. Yet today, we are fully aware scientifically that it is perfectly possible to enjoy health on a purely vegetarian diet. This knowledge stems largely from early research into the nature of proteins, and awareness, after Justus von Leibig’s research in the nineteenth century, that plants contain muscle-building compounds, if not a complete package of amino acids. -

Binnur's Turkish Cookbook: Borek

Binnur's Turkish Cookbook TurkishCookbook.com - Delicious, healthy and easy-to-make Ottoman & Turkish recipes Friday, April 01, 2005 Turkish Cookbook Published: Borek Buy from Amazon.com! Turkish Cookbook: Main: Home Page 7 sheets Phyllo Pastry 2-3 tbsp extra virgin olive oil About this site 1/2 cup milk aStore 2 eggs Flickr 1 pinch salt Measurements 2L pyrex casserole dish Meal Ideas For this recipe, choose one of the following fillings: Links Intl Recipes Spinach Filling (pictured above): Turkce 1 pkg (300 gr) frozen chopped spinach, squeeze it with your hands to get rid of excess water. 1/3 cup crumbled feta Recipe Categories 1 onion, chopped Soups 1 tbsp extra virgin olive oil Appetizers Salt Lamb & Beef Black pepper Kebabs Beef Filling: Meatballs 250 gr medium ground beef Chicken 1 onion, sliced Seafood 2 tomatoes, diced Vegetables 1 small cubanelle pepper, chopped Pilaf Salt Black pepper Pasta Salads For Spinach Filling: Put the salt, pepper, olive oil and onion in a pan. Cook Olive Oil Dishes on medium heat for two minutes. Add the spinach and continue cookingfor Dessert Recipes about 1-2 minutes. Put aside and add the feta cheese, stir. Dairy Desserts For Beef Filling: Put the salt, black pepper, ground beef and onion in a pan. Cakes & Cookies Cook on medium heat until the beef is done. Add the tomatoes and the Pastries pepper. Continue cooking for another 5 minutes. Put aside. Bread & Pide Now we can move on to the main ingredients. In a bowl, mix the eggs, Breakfast & Eggs olive oil and milk with a whisk. -

Italian Food Discovery Pasta Olives Cheese Tomato Legumes Olive Oil Dressings Vegetables Confectionery Foodeast for Foodies

TOMATO VEGETABLES OLIVES LEGUMES PASTA OLIVE OIL DRESSINGS CHEESE CONFECTIONERY DISCOVERY FOOD ITALIAN FOODEAST FOR FOODIES. Foodeast has an English sound, but it’s 100% Italian. We love food and its lovers. We build our way, starting from the unique pleasure of food experience. In Italy, the richness and variety of the cuisine tell the history of all the peoples who over the millennia have crossed this land. All Italian dishes arise from family stories, tradition, care and fantasy. Each ingredient of Italian cuisine has its own origin, its history and its identity and it is often the result of a very ancient knowledge. Moreover, Italian people love sharing good food and enjoying a pleasant experience around food. Foodeast likes to bring Italian food products all over the world, spreading Italian Food culture and allowing Foodies taking a more picture for their delicious handbook. ITALIAN FOOD PRODUCTS HAVE THEIR BRAND. LITALY is a wide collection of selected Italian Food products. It includes the most classical items, such as tomato, pasta and legumes, but also a selection of typical cheese, together with dressings, canned vegetables and confectionery products. All LITALY products are studied to offer the best Italian quality, in the right size and nice packaging, in order to let our Customers have an authentic experience of Italian Food, all over the world. TOMATO VEGETABLES OLIVES LEGUMES PASTA OLIVE OIL DRESSINGS CHEESE CONFECTIONERY LITALY large list of item gives the right answer to all request for | | | | | | | | | Italian Food, in both retail and foodservice market, including also special need from industry. 4 6 7 8 10 12 13 14 16 The main ingredient of several Italian recipes, tomato is the key-factor of almost all global cookings.