New Gleanings from a Jewish Farm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec/Jan 2010

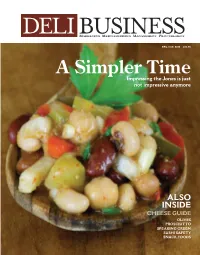

DELI BUSINESS MARKETING MERCHANDISING MANAGEMENT PROCUREMENT DEC./JAN. 2010 $14.95 A Simpler Time Impressing the Jones is just not impressive anymore ALSO INSIDE CHEESE GUIDE OLIVES PROSCIUTTO SPEAKING GREEN SUSHI SAFETY SNACK FOODS DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 COVER STORY CONTENTS DELI MEAT Ah, Prosciutto! ..........................................22 Any way you slice it, prosciutto is in demand FEATURES Snack Attack..............................................32 Consumers want affordable, healthful, cutting-edge snacks and appetizers 14 MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Creating An Olive Showcase ....................19 Time-tested merchandising techniques can boost the sales potential of deli olives 22 Green Merchandising ................................26 Despite a tough economy, consumers still want environmentally friendly products DELI BUSINESS (ISSN 1088-7059) is published by Phoenix Media Network, Inc., P.O. Box 810425, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0425 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to DELI BUSINESS, P.O. Box 810217, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0217 DEC./JAN. 2010 DELI BUSINESS 3 DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 CONTENTS COMMENTARIES EDITOR’S NOTE Good Food Desired In Bad Times ................8 PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS The Return of Cooking ..............................10 MARKETING PERSPECTIVE The New Frugality......................................53 IN EVERY ISSUE DELI WATCH ....................................................12 TECHNEWS ......................................................52 29 BLAST FROM THE PAST ........................................54 -

Read Book the Food of Taiwan Ebook Free Download

THE FOOD OF TAIWAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cathy Erway | 240 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | HOUGHTON MIFFLIN | 9780544303010 | English | Boston, United States The Food of Taiwan PDF Book Part travelogue and part cookbook, this book delves into the history of Taiwan and the author's own family history as well. French Food at Home. Categories: Side dish; Taiwanese; Vegan; Vegetarian Ingredients: light soy sauce; Chinese white rice wine; chayote shoots. Recently, deep-fried vegetarian rolls wrapped in tofu sheets have appeared in this section of the offering. Bowls of sweet or salty soy milk are classic Taiwanese breakfast fodder, accompanied by a feast of spongy, focaccia-like shao bing sesame sandwiches ; crispy dan bing egg crepes ; and long, golden- fried you tiao crullers. Your email address will not be published. Home 1 Books 2. The switch from real animals to noodles was made over a decade ago, we were told, to cut costs and reduce waste. For example, the San Bei Ji was so salty it was borderline inedible, while the Niu Rou Mian was far heavier on the soy sauce than any version I've had in Taiwan. Hardcover , pages. Little has changed over the years in terms of the nature of the ceremony and the kind of attire worn by the participants, but there have been some surprising innovations in terms of what foods are offered and how they are handled. Aside from one-off street stalls and full-blown restaurants, there are a few other unexpected spots for a great meal. I have to roll my eyes when she says that Taiwan is "diverse" even though it has a higher percentage of Han Chinese than mainland China does and is one of the most ethnically homogeneous states in the world. -

The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book All Faculty Scholarship Chapters 9-2009 The irsF t Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks Part of the Food Security Commons, History Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Albala, K. (2009). The irF st Scientific efeD nse of a Vegetarian Diet. In Susan R. Friedland (Eds.), Vegetables (29–35). Totnes, Devon, England: Oxford Symposium/Prospect Books https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/cop-facbooks/86 This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the All Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of the Pacific aF culty Books and Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet Ken Albala Throughout history vegetarian diets, variously defined, have been adopted as a matter of economic necessity or as a form of abstinence, to strengthen the soul by denying the body’s physical demands. In the Western tradition there have been many who avoided flesh out of ethical concern for the welfare of animals and this remains a strong impetus in contemporary culture. Yet today, we are fully aware scientifically that it is perfectly possible to enjoy health on a purely vegetarian diet. This knowledge stems largely from early research into the nature of proteins, and awareness, after Justus von Leibig’s research in the nineteenth century, that plants contain muscle-building compounds, if not a complete package of amino acids. -

The Olive and Imaginaries of the Mediterranean

History and Anthropology ISSN: 0275-7206 (Print) 1477-2612 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ghan20 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley To cite this article: Anne Meneley (2020) The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean, History and Anthropology, 31:1, 66-83, DOI: 10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 Published online: 14 Nov 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 29 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ghan20 HISTORY AND ANTHROPOLOGY 2020, VOL. 31, NO. 1, 66–83 https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2019.1687464 The olive and imaginaries of the Mediterranean Anne Meneley ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This paper explores how the olive tree and olive oil continue to seep Olive oil; Mediterranean; food into imaginaries of the Mediterranean. The olive tree, long lived and anthropology; circulations of durable, requires human intervention to be productive: it is commodities; imaginaries emblematic of the Mediterranean region and the longstanding human habitation of it. Long central to the religious imaginaries and practices of the monotheistic tradition and those which preceded it, olive oil has emerged, in recent decades, as the star of The Mediterranean Diet. This paper, inspired by anthropologists who follow the ‘thing’, also follows the advocates, both scientists and chefs, who tout the scientific research which underpins The Mediterranean Diet’s claims, which critics might consider part of contemporary ideologies of ‘healthism’ and ‘nutritionism’. -

The Agricultural and Food Heritage Evolution of Eating Habits and Taste Between Tradition and Innovation

ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE The agricultural and food heritage Evolution of eating habits and taste between tradition and innovation by Marta Lenzi expert on the history of gastronomy and customs The key facts in brief Today our meals begin with savory and end with sweet, we combine pasta with tomato sauce, we choose what and when to eat. But it was not always like this. Food, as an item of social and cultural identity, is characterized by choices and preferences that have changed over the centuries. Taste follows from flavor and is an individual sensation. But, we must also realize that it’s influenced by cultural, economic and social circumstances. At the root of the traditions there are gastronomic influences resulting from the meeting of different cultures, a continuous exchange between peoples. In recent decades, the globalized food model has been established, offering everything and more, at any time, even at the risk of losing our specialties and identity. Our agricultural and food heritage, combined with a greater awareness of the value of food, becomes the starting point for reassessing the local cuisine, understood as a combination of tradition, creativity and innovation. Consumers have realized that foods form a cumulation of history, rediscovering its roots, having a new interest in products and gastronomic specialties that are today better and more reliable thanks to innovations in the industry. 1 The agricultural and food heritage by Marta Lenzi ITALY-SWITZERLAND EXPO 2015 LEARN DEVELOP SHARE To better understand: a few basic concepts Garum: a type of fermented fish sauce typical of the Roman period, obtained from the intestines and other parts of fish waste, marinated in salt, mixed with spices, herbs, oil, vinegar, honey, wine, figs and dates. -

The Use of Food to Signify Class in the Comedies of Carlo Goldoni 1737-1762

ABSTRACT Title of Document: “THE SAUCE IS BETTER THAN THE FISH”: THE USE OF FOOD TO SIGNIFY CLASS IN THE COMEDIES OF CARLO GOLDONI 1737-1762. Margaret Anne Coyle, Ph.D, 2006 Directed By: Dr. Heather Nathans, Department of Theatre This dissertation explores the plays of Venetian Commedia del’Arte reformer- cum-playwright Carlo Goldoni, and documents how he manipulates consumption and material culture using fashionable food and dining styles to satirize class structures in eighteenth century Italy. Goldoni’s works exist in what I call the “consuming public” of eighteenth century Venice, documenting the theatrical, literary, and artistic production of the city as well as the trend towards Frenchified social production and foods in the stylish eating of the period. The construction of Venetian society in the middle of the eighteenth century was a specific and legally ordered cultural body, expressed through various extra-theatrical activities available during the period, such as gambling, carnival, and public entertainments. The theatrical conventions of the Venetian eighteenth century also explored nuances of class decorum, especially as they related to audience behavior and performance reception. This decorum extended to the eating styles for the wealthy developed in France during the late seventeenth century and spread to the remainder of Europe in the eighteenth century. Goldoni ‘s early plays from 1737 through 1752 are riffs on the traditional Commedia dell’Arte performances prevalent in the period. He used food in these early pieces to illustrate the traditional class and regional affiliations of the Commedia characters. Plays such as The Artful Widow, The Coffee House, and The Gentleman of Good Taste experimented with the use of historical foods styles that illustrate social placement and hint at further character development. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF NUTRITIONAL SCIENCES THE MEANING OF ―DIET:‖ A CROSS-CULTURAL COMPARISON OF AMERICAN AND ITALIAN FOOD CULTURES AND LINKS TO OBESITY DIANA ZAHURANEC Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Anthropology, Italian, and International Studies with honors in Nutritional Sciences Reviewed and approved* by the following: Dorothy Blair Assistant Professor of Nutrition Thesis Supervisor Rebecca Corwin Associate Professor of Nutritional Neuroscience Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This research examines the discrepancy between the rising obesity rate in America and the focus on dieting by comparing American and Italian food cultures. My hypothesis is that in State College, Pennsylvania and Lewisburg, West Virginia, Americans‘ perception of diet exemplifies the fundamental difference between American and Italian food cultures because Americans see diet as an action with weight loss intent, while Italians see it as a lifestyle. It is this seemingly small cultural difference that embodies the different relationships between consumer and seller, and consumer and food, in both countries. It shows the importance of past and contemporary influences in affecting the modern-day diet of a country‘s culture, and thus the health of the country‘s populace. The American and Italian food cultures are complex and intertwined with a myriad of influences which I am unable to cover within the scope of this research. This is primarily an anthropological study of both contemporary cultures, with my observations and responses guiding the similarities and differences between American and Italian food cultures and the links to rising obesity rates. -

Cultural Hybridity in the USA Exemplified by Tex-Mex Cuisine

International Review of Social Research 2017; 7(2): 90–98 Research Article Open Access Małgorzata Martynuska* Cultural Hybridity in the USA exemplified by Tex-Mex cuisine DOI 10.1515/irsr-2017-0011 instead it builds on approaches which maintain that Received: February 1, 2016; Accepted: December 20, 2016 cultures are interconnected and deeply intertwined. Abstract: The article concerns the hybrid phenomenon Thus, transculturation rests upon a continuous change of Tex-Mex cuisine which evolved in the U.S.-Mexico and transformation of cultures (Flüchter and Schöttli, borderland. The history of the U.S.-Mexican border area 2015: 2). ‘While transculturation may include processes makes it one of the world’s great culinary regions where of deculturation and acculturation, it goes beyond loss different migrations have created an area of rich cultural and acquisition: transculturation involves the dynamic exchange between Native Americans and Spanish, and fusion and merging of cultures to produce new identities, then Mexicans and Anglos. The term ‘Tex-Mex’ was cultures and societies’ (Knepper, 2011: 256). Transcultural previously used to describe anything that was half-Texan processes are specially visible in borderlands such as the and half-Mexican and implied a long-term family presence U.S. Southwest / Mexican border where American and within the current boundaries of Texas. Nowadays, the Mexican cultures create cultural hybridity. term designates the Texan variety of something Mexican; The term ‘hybridity’ was first applied to agriculture, it can apply to music, fashion, language or cuisine. genetics and combinations of different animals. Then, it Tex-Mex foods are Americanised versions of Mexican entered social science, anthropology and linguistics. -

Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past

Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past Maria Dembin'ska Translated by Magdalena Thomas Revised and Adapted by William Woys Weaver UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS PHILADELPHIA In Memory of Henryk Dembinski (1911-1987) ix Editori Preface Three Latln words scribbled in the margin of the parchment WILLIAM WOYS WEAVER ledger book of Polish royal treasurer Henryk of Rog6w -ad regakm xxi List oflflu~tration~ scutellum, for the royal pot-not only extended a proprietary reach over the markets and gardens of medieval Poland; they also conjured 1 Chapter 1. Toward a Definition of Polish National Cookey up a court cuisine unique to Central Europe. Strangely Oriental, yet 25 Chapter 2. Poland in the Middle Ages peasantlike in its robust simplicity, it was a cookery that captured 47 Chapter 3. The Dramatis Personae ofthe Oid Polish Table all the complexities of Poland in that far-off age, a nation of great power slowly twisting toward upheaval, of farmlands and towns 7 1 Chapter 4. Food and Drink in Medzeval Poland thronging with emigrants from cultures unable to meld with the Pol- 137 Medieval Recipes rn the Polish Style ish countryside around them. And yet for a time, it was also a rare W~LLLAMWOYS W EAVER period of peace. Maria Demblnska went back to the royal account 201 Notes books - indeed, to all the medieval records she could find- in order 209 Bibliography to reconstruct this chapter of Poland's history. Her work is now a scholarly classic. 2 19 Acknowledgments Maria Dembinska's research was originally prepared in 1963 223 Inifex as a doctoral dissertation at Warsaw University and the Institute of Material Culture of the Polish Academy of Science. -

Heidi Krahling

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Heidi Krahling RESTAURANTEUR, CHEF AND PROTÉGÉ OF TANTE MARIE’S COOKING SCHOOL An Interview Conducted by Paul Redman in 2004 Copyright © 2005 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Heidi Krahling, dated December 11, 2004. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Speciality Regional Foods in the UK: an Investigation from the Perspectives of Marketing and Social History

Speciality Regional Foods in the UK: an Investigation from the Perspectives of Marketing and Social History by Angela Tregear NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 200 20971 4 -7c(va.s\% \,\;)%za A thesis submitted to the University of Newcastle upon Tyne for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy No portion of the work referred to in this thesis has been submitted in support of an application for any other degree or qualification from this, or any other, University or institute of learning April 2001 "Just at the moment when food has become plentiful thanks to an incredible assortment of products and unprecedented purchasing power, our relationship with it paradoxically has become more distant. We know not whence it comes, nor when or how it has been made." (Massimo Montanari, 1994) Abstract This thesis concerns an investigation of the nature and meaning of speciality regional foods in the UK, by examining the products themselves as well as the producers who bring them to the marketplace. Speciality regional food production is making an increasingly important contribution to the economy and is pertinent to newly evolving policy objectives in the agrifood and rural sectors at both national and European Union levels. In spite of this, many uncertainties exist with respect to the properties of speciality regional foods and the characteristics and behaviour of the producers of these foods. In the literature review, territorial distinctiveness in foods is identified as comprising geophysical and human facets, these being influenced over time by macro-environmental forces such as trade and industrialisation. Territorial distinctiveness is also identified as comprising a range of end product qualities perceived by consumers. -

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2014 Daniele De Feo ALL RIGHTS RESERVED IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Italian Written under the direction of Professor Paola Gambarota And approved by _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January, 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION IL GUSTO DELLA MODERNITÀ: AESTHETICS, NATION, AND THE LANGUAGE OF FOOD IN 19TH CENTURY ITALY By DANIELE DE FEO Dissertation Director Professor Paola Gambarota My dissertation “Il Gusto della Modernità: Aesthetics, Nation and the Language of Food in 19th century Italy,” explores the cohesive pedagogic and nationalistic attempt to define Italian taste during the instability of an unificatory Italy. Initiating with an establishing European taste paradigm (e.g. Feuerbach, Fourier, Brillat-Savarin), my research demonstrates that there is an increasing number of works composed within the developing “Italian” context, which reflects and participates in the construction and the consumption of a national identity (e.g., Rajberti, Mantegazza, Guerrini, Artusi). Conversely, this budding taste genre finds itself in sharp contrast to the economic paucity and social divisiveness endured by a large sector of the populace and depicted by the literature of the day (e.g., Collodi, Verga, Serao). It is precisely this lack of confluence between that which is scientific and literary that marks this process of taste ennoblement and indoctrination, defining more than ever the nuances that encompass il gusto italiano.