The Use of Food to Signify Class in the Comedies of Carlo Goldoni 1737-1762

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10-12-2019 Turandot Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Legendary Peking. Outside the Imperial Palace, a mandarin reads an edict to the crowd: Any prince seeking to marry Princess Turandot must answer three riddles. If he fails, he will die. The most recent suitor, the Prince of Persia, is to be executed at the moon’s rising. Among the onlookers are the slave girl Liù, her aged master, and the young Calàf, who recognizes the old man as his long-lost father, Timur, vanquished King of Tartary. Only Liù has remained faithful to the king, and when Calàf asks her why, she replies that once, long ago, Calàf smiled at her. The mob cries for blood but greets the rising moon with a sudden fearful reverence. As the Prince of Persia goes to his death, the crowd calls upon the princess to spare him. Turandot appears in her palace and wordlessly orders the execution to proceed. Transfixed by the beauty of the unattainable princess, Calàf decides to win her, to the horror of Liù and Timur. Three ministers of state, Ping, Pang, and Pong, appear and also try to discourage him, but Calàf is unmoved. He reassures Liù, then strikes the gong that announces a new suitor. Act II Within their private apartments, Ping, Pang, and Pong lament Turandot’s bloody reign, hoping that love will conquer her and restore peace. Their thoughts wander to their peaceful country homes, but the noise of the crowd gathering to witness the riddle challenge calls them back to reality. In the royal throne room, the old emperor asks Calàf to reconsider, but the young man will not be dissuaded. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

La Cultura Italiana

LA CULTURA ITALIANA BALDASSARE GALUPPI (1706–1785) Thousands of English-speaking students are only familiar with this composer through a poem by Robert Browning entitled “A Toccata of Galuppi’s.” Few of these students had an inkling of who he was or had ever heard a note of his music. This is in keeping with the poem in which the toccata stands as a symbol of a vanished world. Although he was famous throughout his life and died a very rich man, soon after his death he was almost entirely forgotten until Browning resurrected his name (and memory) in his 1855 poem. He belonged to a generation of composers that included Christoph Willibald Gluck, Domenico Scarlatti, and CPE Bach, whose works were emblematic of the prevailing galant style that developed in Europe throughout the 18th century. In his early career he made a modest success in opera seria (serious opera), but from the 1740s, together with the playwright and librettist Carlo Goldoni, he became famous throughout Europe for his opera buffa (comic opera) in the new dramma giocoso (playful drama) style. To the suc- ceeding generation of composers he became known as “the father of comic opera,” although some of his mature opera seria were also widely popular. BALDASSARE GALUPPI was born on the island of Burano in the Venetian Lagoon on October 18, 1706, and from as early as age 22 was known as “Il Buranello,” a nickname which even appears in the signature on his music manuscripts, “Baldassare Galuppi, detto ‘Buranello’ (Baldassare Galuppi, called ‘Buranello’).” His father was a bar- ber, who also played the violin in theater orchestras, and is believed to have been his son’s first music teacher. -

Download Download

Angelica Forti-Lewis Mito, spettacolo e società: Il teatro di Carlo Gozzi e il femminismo misogino della sua Turandot Alla Commedia dell'Arte Carlo Gozzi si rifece, almeno inizialmente, perché gli offriva uno spettacolo da contrastare al teatro di Goldoni, di Chiari e, più tardi, al nuovo dramma borghese e alla comédie larmoyante. A questo scopo l'Improvvisa poteva offrirgli aiuti preziosi: la teatralità pura degli intrecci, svincolati da ogni rapporto con la vita reale e contemporanea; le Maschere, cioè tipizzazioni astrat- te; il buffonesco delle trovate comiche che, insieme alle maschere, escludeva ogni possibile idealizzazione delle classi inferiori, degradate a oggetto di comico; e, infine, il carattere nazionale della Commedia, che escludeva qualsiasi intrusione forestiera. Ma anche se Gozzi si erge a strenuo difensore della Commedia dell'Arte, è chiaro che le sue fiabe hanno in realtà ben poco a che fare con l'Improvvisa e il loro tono, sempre dominato da personaggi seri, è ben più drammatico, mentre le varie trame non sono ricavate dalla solita tradizione scenica ma da racconti ita- liani ed orientali, nel loro adattamento teatrale parigino della Foire. L'esotismo e la magia, inoltre, erano anch'essi elementi ignoti alla Commedia dell'Arte e la lo- ro fusione con la continua polemica letteraria sono chiara indicazione di come il commediografo fosse ben altro che un mero restauratore di scenari improvvisati. Trionfano nelle fiabe i valori tradizionali, dall'amor coniugale {Re Cervo, Tu- randot, Donna serpente e Mostro Turchino), all'amore fraterno, la fedeltà e la virtù della semplicità (Corvo, Pitocchi fortunati e Zeim re de' Geni). -

Dining Osteria Enoteca San Marco Osteria Da Fiore

A quest for authentic Italian food in Venice! To learn more about our tours, visit us at www.theromanguy.com Dining Osteria Enoteca San Marco CALLE FREZZERIA, 1610 (NEAR ST MARK’S SQUARE) - TEL: +39 041 5285242 A popular spot on the main island in Venice, with over 300 types of wine and a delicious menu, it is hard to go wrong here. Meat, fish, game and vegetable plates are presented with a modern twist on traditional Italian flavors. The menu is seasonal, with the use of fresh produce, so you can guarantee everything you eat is fresh! Wash it all down with a quality Italian wine and enjoy the tastes of Venice. PRICE: AMBIANCE: – RSVP: 12:30 pm - 11 pm a must! Osteria da Fiore SAN POLO, 2202 (NEAR RIALTO BRIDGE) - TEL: +39 041 721308 Focusing on fish that has been caught in the local harbor, this family run restaurant has made its name by cooking up a storm with the seafood recipes that have passed down through the Martin family for generations. Do not pass up on the seafood risotto! PRICE: AMBIANCE: – RSVP: Tue - Sat: 12:30 pm - 2 pm at the door 7 pm - 10:30 pm Quadri PIAZZA SAN MARCO (ST MARK’S SQUARE) - TEL: +39 041 5222105 Our top pick for fine dining on the island has got to be this Michelin star gem, located in the heart of Venice in St. Mark’s square. Words escape us as to how good some of the food is in this restaurant, but it comes at a price! If you're looking for a luxury experience then service, attention to detail and exquisite food at Quadri will certainly fit the bill. -

Italy's Most Popular Aperitivi

Italy’s Most Popular Aperitivi | Epicurean Traveler https://epicurean-traveler.com/?p=96178&preview=true U a Italy’s Most Popular Aperitivi by Lucy Gordan | Wine & Spirits Italy is world famous for its varied regional landscapes, history, food and accompanying wines. However, if you go straight out to dinner, you’ll be missing out on a quintessential tradition of la bella vita, because, when they have time, self-respecting Italians, especially in the north and in big cities, start their evening with an aperitivo or pre-diner drink. An aperitivo is not “Happy Hour” or an excuse to drink to oblivion. Italians blame many ailments on their livers so the aperitivo has digestive purposes. It allows Italians to relax, unwind and socialize after work. It also starts their digestive metabolism and gets the juices flowing with a light, dry or bitter tonic with a “bite” to work up their appetite before dinner. This so-called “bitter bite” is beloved to Italians who prefer it and the overly sweet to sour. It took me several years to get used to bitter, much less like it. The oldest aperitivo is vermouth, an aromatic fortified wine created in Turin, where the aperitivo tradition is still strongest today. As www.selectitaly.com tells us: “ One of the oldest vermouths dates back to 1757 when two herbalist brothers, Giovanni Giacomo and Carlo Stefano Cinzano created vermouth rosso, initially marketed as a medicinal tonic.” This explains the bitter quality of many Italian drinks even non-alcoholic ones like chinotto or crodino. The Cinzano brothers flavored their vermouth, (its name derived from the German wormwood), with Wermut, its main ingredient, and with over 30 aromatic plants from the nearby Alps: herbs, barks, and roots such as juniper, gentian and coriander. -

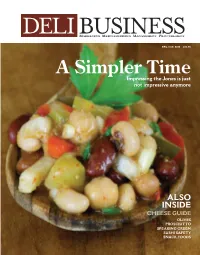

Dec/Jan 2010

DELI BUSINESS MARKETING MERCHANDISING MANAGEMENT PROCUREMENT DEC./JAN. 2010 $14.95 A Simpler Time Impressing the Jones is just not impressive anymore ALSO INSIDE CHEESE GUIDE OLIVES PROSCIUTTO SPEAKING GREEN SUSHI SAFETY SNACK FOODS DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 COVER STORY CONTENTS DELI MEAT Ah, Prosciutto! ..........................................22 Any way you slice it, prosciutto is in demand FEATURES Snack Attack..............................................32 Consumers want affordable, healthful, cutting-edge snacks and appetizers 14 MERCHANDISING REVIEWS Creating An Olive Showcase ....................19 Time-tested merchandising techniques can boost the sales potential of deli olives 22 Green Merchandising ................................26 Despite a tough economy, consumers still want environmentally friendly products DELI BUSINESS (ISSN 1088-7059) is published by Phoenix Media Network, Inc., P.O. Box 810425, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0425 POSTMASTER: Send address changes to DELI BUSINESS, P.O. Box 810217, Boca Raton, FL 33481-0217 DEC./JAN. 2010 DELI BUSINESS 3 DEC./JAN. ’10 • VOL. 14/NO. 6 CONTENTS COMMENTARIES EDITOR’S NOTE Good Food Desired In Bad Times ................8 PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS The Return of Cooking ..............................10 MARKETING PERSPECTIVE The New Frugality......................................53 IN EVERY ISSUE DELI WATCH ....................................................12 TECHNEWS ......................................................52 29 BLAST FROM THE PAST ........................................54 -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Polemics and the Emergence of the Venetian Novel: Pietro Aretino, Piero Chiari, and Carlo Gozzi Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1sm8g0zm Author Stanphill, Cindy D Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Polemics and the Emergence of the Venetian Novel: Pietro Aretino, Piero Chiari, and Carlo Gozzi A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian by Cindy Diane Stanphill 2018 ã Copyright by Cindy Diane Stanphill 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Polemics and the Emergence of the Venetian Novel: Pietro Aretino, Piero Chiari, and Carlo Gozzi by Cindy Diane Stanphill Doctor of Philosophy in Italian University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Massimo Ciavolella, Chair Pietro Chiari (1712-1785) and Carlo Gozzi (1720-1806) are well-known eighteenth-century Italian playwrights. Their polemical relationship has been the object of many studies, but there is a dearth of work dedicated to their narratives and novels, with none in English language scholarship, though a small and growing number of Italian studies of the novelistic genre in eighteenth-century Italy has emerged in recent years. In my dissertation entitled, Polemics and the Rise of the Venetian Novel: Pietro Aretino, Piero Chiari, and Carlo Gozzi, I examine the evolution of the Italian novel in a Venetian context in which authors, some through translation, some through new work, vie ii among themselves for the center in the contest to provide literary models that will shape and educate the Venetian subject. -

Carlo Goldoni and Commedia Dell'arte

THE MASK BENEATH THE FACE: CARLO GOLDONI AND COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE In the published script for One Man, Two Guvnors, each character description is followed by a fancy-sounding Italian name. FEBRUARY 2020 These are stock character types from WRITTEN BY: commedia dell’arte, an Italian form of KEE-YOON NAHM improvised comedy that flourished from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. How does Richard Bean’s modern comedy adapt this tradition? What exactly is the relationship between Francis Henshall and Truffaldino? To answer that question, we must look at the life and career of one Carlo Goldoni, a Venetian playwright who lived in the eighteenth century. His most famous play, The Servant of Two Masters (1753) was about a foolish tramp who tries to serve two aristocrats at the same time. Goldoni borrowed heavily from commedia 1 characters and comic routines, which were popular during his time. In turn, Bean adapted Goldoni’s comedy in 2011, setting the play in the seedy underworld of 1960s Brighton. In other words, Goldoni is the middleman in the story of how a style of popular masked theatre in Renaissance Italy transformed into a modern smash-hit on West End and Broadway. Goldoni’s parents sent him to school to become a lawyer, but the theatre bug bit him hard. He studied ancient Greek and Roman plays, idolized the great comic playwright Molière, and joined a traveling theatre troupe in his twenties. However, Goldoni eventually grew dissatisfied with commedia dell’arte, which could be inconsistent and haphazard because the performers relied so much on improv and slapstick. -

May 30, 2014 Vol. 118 No. 22

VOL. 118 - NO. 22 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, MAY 30, 2014 $.35 A COPY Walsh, Forry and New Plans for Trash Collection 3:00 am Nightlife? by Sal Giarratani A 3:00 am closing could be happening sooner than we think. The State Senate is considering amendments to the fiscal 2015 budget proposal and Mayor Marty Walsh apparently has dusted off some of his legislative prowess gathered over 17 years on Beacon Hill by teaming up with Sen. Linda Dorcena Forry on an amendment that allows communities to control their own sale of alcohol later than the current 2:00 am deadline. Forry’s measure would allow communities to go beyond the 2:00 am mandatory deadline in cities and towns that are serviced by MBTA late-night service. Walsh has made it clear, he sees the possibility of clos- ings of bars and restaurants as late as 3:30 am in order to add to Boston’s reputation as a world-class city. Mayor Martin J. Walsh and the Depart- on Tuesday and Friday, and recycling col- Apparently, the powers that be at City Hall think this would ment of Public Works announced new lection will take place on Tuesday and help the city’s economic growth and that it would also ben- collection hauling and disposal contracts, Friday. efit from more entertainment, transportation, food and effective July 1, 2014 until the end of the • North End will be serviced by Sunrise drink from all those burning well beyond the midnight oil. contract term in fiscal year 2019. Scavenger. Trash collection will take place There are many folks who think later closing hours is a “I’m concerned for the environment and on Monday and Friday, and recycling collec- great idea but there are also others such as North End resi- we have to do our part by protecting our tion will take place on Monday and Friday. -

Representações Do Feminino Em La Locandiera E La Putta Onorata, De Carlo Goldoni

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO ESPÍRITO SANTO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS CAROLINE BARBOSA FARIA FERREIRA REPRESENTAÇÕES DO FEMININO EM LA LOCANDIERA E LA PUTTA ONORATA, DE CARLO GOLDONI Vitória 2019 CAROLINE BARBOSA FARIA FERREIRA REPRESENTAÇÕES DO FEMININO EM LA LOCANDIERA E LA PUTTA ONORATA, DE CARLO GOLDONI Tese apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras do Centro de Ciências Humanas e Naturais da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutora em Letras, na área de concentração Estudos Literários. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Paula Regina Siega Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. André Luís Mitidieri Vitória 2019 Aos meus pais Aos meus amados Gilberto e Levi. AGRADECIMENTOS A Deus, porque sei que sem Ele nada seria possível. Aos meus amados Gilberto e Levi, pelo grande amor, incentivo, apoio, compreensão, paciência e ajuda em todos os momentos. Aos meus pais, Claudio e Shirley, porque sempre acreditaram em mim e me fazerem crer que eu poderia ir além. À minha orientadora, Profa. Dra. Paula Regina Siega, pela grande amizade, atenção, solicitude, e confiança no meu trabalho. Ao meu co-orientador, Prof. Dr. André Luis Mittidieri, por todo o auxílio no meu Exame de Qualificação e durante a escritura da tese. À Profa. Dra. Ester Abreu Vieira de Oliveira, pelas disciplinas de teatro que tanto enriqueceram os meus conhecimentos, e pelos valorosos comentários, questionamentos e observações em meu Exame de Qualificação. A todos os meus colaboradores, aqui no Brasil e na Itália, que me enviaram artigos e livros, sem os quais não poderia certamente ter construído esta tese. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a