Contentious Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2012 Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (2012). Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_research/summary/v079/ 79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Keywords Satire, Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, Jon Stewart Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics Comments Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ social_research/summary/v079/79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. -

Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to Open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 11, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Amy E. S. Maier, B&P PR, 702-372-9919, [email protected] Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino on April 18 Tweet it: Get ready to laugh as @BonkerzComedy Club brings its hilarious comedians to entertain audiences @Plazalasvegas starting April 18 LAS VEGAS – The Plaza Hotel & Casino will be the new home of the historic Bonkerz comedy club and its cadre of comedy acts beginning April 18. Bonkerz Comedy Productions opened its doors in 1984 and has more than two dozen locations nationwide. As one of the nation’s longest-running comedy clubs, Bonkerz has been the site for national TV specials on Showtime, Comedy Central, MTV, Fox and “America´s Funniest People.” Many of today’s hottest comedians have taken their turn on the Bonkerz Comedy Club stage, including Larry The Cable Guy, Carrot Top, SNL co-star Darrell Hammond and Billy Gardell, star of the CBS hit sitcom “Mike and Molly.” Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo has a long history of successful comic casting and currently consults with NBC’s “America’s Got Talent.” “Bonkerz has always had an outstanding reputation for attracting top-tier comedians and entertaining audiences,” said Michael Pergolini, general manager of the Plaza Hotel and Casino. “As we continue to expand our entertainment offerings, we are proud to welcome Bonkerz to the comedy club at the Zbar and know its acts will keep our guests laughing out loud.” “I am extremely excited to bring the Bonkerz brand to an iconic location like the Plaza,” added Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo. -

Curb Your Enthusiasm,” Ed Asner Walks Into His New Lawyer’S Office to Discuss His Vast Estate When the Lawyer Greets Him, Iwarmly, Wearing Jeans and a Polo Shirt

APPEARANCES DO MATTER By David S. Wolf n a very funny scene from Larry David’s HBO comedy series “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” Ed Asner walks into his new lawyer’s office to discuss his vast estate when the lawyer greets him, Iwarmly, wearing jeans and a polo shirt. Asner’s character is taken aback by the lawyer’s outfit, asking if he is going to a “Halloween party.” The lawyer attempts to put Asner at ease, advising him that it is “casual Friday.” Asner responds by telling the lawyer that he looks like a “f—cowboy.” The lawyer’s efforts to put the prospective client at ease, assuring him that his estate would not be handled “casually,” fall on deaf ears, and Asner, outraged, leaves in a huff, large retainer in hand. When I served as a law clerk in the early 1980s to a $5 donations to various charities in exchange for “jeans day.” Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas judge, I was forbidden to While I appreciate the charitable aspect of these initiatives, walk out of chambers without wearing my suit jacket and tie, I am afraid this overall attempt at morale boosting has despite the frequent breakdown of City Hall’s air conditioning encroached into legal events, especially at civil depositions, system. When I worked for an in-house insurance firm, I was where some of my colleagues have taken this relaxed dress required to wear a suit and tie, even if my day was to be spent code to the extreme. in solitude behind a desk. Decorum, generally, at depositions is not what it used to be. -

How Does Context Shape Comedy As a Successful Social Criticism As Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’S SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2012 How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?” Abigail Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Abigail, "How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”" (2012). Honors College. 58. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/58 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DOES CONTEXT SHAPE COMEDY AS A SUCCESSFUL SOCIAL CRITICISM AS DEMONSTRATED BY EDDIE MURPHY’S SNL SKETCH “WHITE LIKE ME?” by Abigail Jones A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Communications) The Honors College University of Maine May 2012 Advisory Committee: Nathan E. Stormer, Professor of Communication, Advisor Kristin M. Langellier, Professor of Communication Sandra Hardy, Associate Professor of Theater Mimi Killinger, Honors College Rezendes Preceptor for the Arts Adam Kuykendall, Marketing Manager for the School of Performing Arts Abstract This thesis explores the theory of comedy as social criticism through an interpretive investigation. For comedy to be a potent criticism it is important for the audience to understand the context surrounding the sketch. Without understanding the context the sketch still has the ability to be humorous, but the critique is harder to acknowledge. -

Hbo Premieres All New Series Girls and Veep

HBO PREMIERES ALL NEW SERIES GIRLS AND VEEP Miami, July 9, 2012 – HBO Latin America announced that Girls and Veep, two new original comedies, will premiere on July 23. The first episode of both productions will be available on www.hbomax.tv after they air onscreen. Girls is a comedy directed by Lena Dunham, the up-and-coming filmmaker and actor, who also stars in the series. Veep stars Emmy®-award-winning actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus, who has starred in popular series like Seinfield and Curb your Enthusiasm. Created and led onscreen by Lena Dunham, Girls takes a comic look at the assorted humiliations and rare triumphs of a group of women in their early 20s living in New York City. The series, which has already been renewed for a second season, focuses on the girls’ adventures in post-collegiate floundering. A fresh and intimate look at friendship, relationships and self-discovery, Girls is a contemporary coming-of-age show that packs humor, farce and poignancy into each episode. Through four distinct characters, who may seem unlikely friends to some, Girls shines through as a voice of the post-recession generation who can hardly afford lunch, let alone Manolos. In addition to Lena Dunham as the anxious, rumpled Hannah, the cast of Girls includes Jemima Kirke as the beautiful Jessa, allergic to all things bourgeois; Allison Williams as Marnie, Hannah’s uptight roommate with strict rules about their best-friendship; Zosia Mamet (Mad Men) as Shoshanna, an NYU student and Jessa’s self-help obsessed roommate and cousin; and Adam Driver (HBO’s You Don’t know Jack) As Hannah’s love interest, Adam. -

American Comedy in Three Centuries the Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile

American Comedy in Three CenturieS The Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile James R. Bowers Abstract This paper is a survey of the development of American comedy since the United States became an independent nation. A representative play was selected from the 18th century(Royall Tyler’s The Contrast), the 19th century(Anna Cora Mowatt’s Fashion)and the 20th century(Neil Simon’s Califoグnia Suite). Asummary of each play is丘rst presented and then fo110wed by an analysis to determine in what ways it meets or deviates from W. D, Howarth’s minimal de且nition of comedy. Each work was found to conform to the definition and to possess features su岱ciently distinct for it to be classified as a masterpiece of its time. Next, the works were analyzed to derive from them unique features of American comedy. The plays were found to possess distinctive elements of theme, form and technique which serve to distinguish them as Ameri. can comedies rather than Europeal1, Two of these elelnents, a thematic concern with identity as Americans and the technical primacy of dialog and repartee for the stimulation of laughter were found to persist into present day comedy. Other elements:characterization, subtlety of form -145一 and social relevance of theme were 6bserved to have evolved over the centuries into more complex modes. Finally, it was noted that although the dominant form of comedy iロthe 18th and 19th centuries was an American variant of the comedy of man- ners, the 20th century representative Neil Simon seems to be evolving a new form I have coined the comedy -

Spike Lee Discusses Struggles in Directing

• - ···~. ,.. Ai~inghigh ;. Meaningful music. Index · ACC :aspirations · Exile arid age help A&E 85-8 Deacon Notes 82 ·.. group:pteJent::/. Briefly A2 Editorials A6-7 ........ ,, ~-" t•···~-- ..... - ~ ... ~·- ·~·&··: Calendar 86 Scoreboard 83 ::...idea]'lftoleratlin Cla8sifieds · 88 Sports 81-3 " '·• w~.~ ' 0< --~•.,.•"'-•'' ·: :A&E/85 ~:· : Comics 86 WorldWide A4 Visit our Web site at http:!Iogb. wtu.edu l I Volume 82, No. 11 •' . ·- . 0. pl~dgingsu~pended by nationals .. ' . \' . ,. ' ... ·... =.. ' ' l .. J ·~Y Travis Langdon .· . course of its involvement at the university, . After a series ofpledging difficulties and lot to do with the fact that I was kicked out, ' Assistant News Editor incffding an· AIDS taSk force, outreach to · Although it is not being investigated personal conflicts, the pledge was removed which gave me the freedom to help out the ! chil~tln. and 'underprivileged .community from the fraternity by the organization's pledges who shared my concerns. Most of l The Kappa Theta chapter of Alph* Phi meri)be~, ai4·to local veterinary clinics and QY the university, t~e organization had executives. Immediately after being dis the APO pledges get involved because they Omega; a coed fraternity dedicated.to lead parti'J;:ipation in the Special Olympics. its pledge program officially missed, the pledge learned ofanother viola want to do community service, and that's a ership and' community service, is currently H .,,llPllii>l' although it is riot being inv:es- · ·· suspended 0Ct..29. tion involving three pledges that was said to good thing. That's why people are sup under administrative review by its national the university, the org~:2;ation . -

Production Biographies

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES MIKE O’MALLEY (Executive Producer & Showrunner, Writer- 201, 207, 210) Truly a multi-hyphenate, Mike O’Malley got his start in front of the camera hosting Nickelodeon’s “Get the Picture” and the iconic game show “Guts”. His success continued in television with standout roles in “Yes Dear”, “My Name Is Earl”, “My Own Worst Enemy”, “Justified”, and his Emmy®-nominated, groundbreaking performance as ‘Burt Hummel’ on the hit show “Glee”. Mike’s feature work includes roles in Eat Pray Love, Cedar Rapids, Leatherheads, Meet Dave, 28 Days, and the upcoming Untitled Concussion Project starring Will Smith which will be released Christmas 2015. Also an accomplished writer, Mike wrote and produced the independent feature Certainty which he adapted from his own play. In television, Mike has served as a Consulting Producer on “Shameless” and is in his second season as creator and Executive Producer of “Survivor’s Remorse” for Starz. LEBRON JAMES (Executive Producer) LeBron James is widely considered one of the greatest athletes of his generation. James’ extraordinary basketball skills and dedication to the game have won him the admiration of fans across the globe, and have made him an international icon. Prior to the 2014-2015 season, James returned to his hometown in Ohio and rejoined the Cleveland Cavaliers in their mission to bring a championship to the community he grew up in. James had previously spent seven seasons in Cleveland after being drafted out of high school by his hometown team with the first overall pick in the 2003 NBA Draft. James led the Cavaliers to five straight NBA playoff appearances and earned six All-Star selections during his first stint in Cleveland. -

TEXAS IMPROV COMEDY CLUBS by Hannah Kaitlyn Chura, BA Sport

Chura 1 DIGITAL BRAND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY: TEXAS IMPROV COMEDY CLUBS by Hannah Kaitlyn Chura, B.A. Sport Management, B.A. Fine Arts Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Department of Strategic Communication Bob Schieffer School of Communication Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Science May 2016 Chura 2 Project Advisors: Jong-Hyuok Jung, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Strategic Communication Wendy Macias, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Strategic Communication Catherine Coleman, Associate Professor of Strategic Communication Chura 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………p.4 2. Situation Analysis……………………………………………………………………...p.6 3. Literature Review………………………………………………………….…………p.10 4. Method…………………………………………………………………….…………..p.16 5. Results…………………………………………………………...…………………….p.20 6. Implications…………………………………………………...………………………p.29 7. Limitations and Future Research……………………………………………………p.33 8. Reference……………………………………………………………………….……..p.35 9. Appendix………………………………………………………………………………p.37 Chura 4 INTRODUCTION Digital media threatens the profits of the entrainment industry. The variety of options offered by digital platforms such as Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube introduces new competitors to physical entertainment venues, such as comedy clubs. IBIS World Report suggests that the comedy club industry generates $315.1 million annually in the United States. However, while the industry itself is growing, digital entertainment venues (e.g., Netflix, Hulu, Vimeo, and YouTube) threaten the future of physical stand-up clubs (Edwards, 2015). This potential substitute has left stand-up comedy clubs, like the Texas Improv Comedy Clubs, questioning if they can maintain their brand identity, while potentially leveraging new media to their advantage. Overview In 1963, the Improvisation Comedy Club, or Improv, started in New York City by Budd Friedman as a venue for Broadway performers to relax after their shows. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

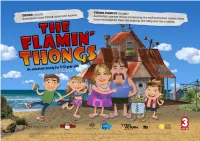

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

The Farce Element in Moliere

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1-1926 The farce element in Moliere. Louise Diecks University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Diecks, Louise, "The farce element in Moliere." (1926). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 344. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/344 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE THE FARCE ELEMENT IN MOLIERE A DISSERTATION ---' SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE --- REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES. BY LOUISE DIECKS 1 9 2 6 I N T ROD U C T ION To gain a true appreciation of the works of any author, we must first be familiar with his race, his environment, and the period in which and of which he wrote. The Paris of the early seventeenth century was far different from the modern metropolis of to-day. It was the Paris of ill-paved, badly lighted streets whe te beggar and peasant starved and marquises rolled by in their emblazoned coaches, where d'Artagnan and the King's musketeers spread romance and challenged authority and where conspiracy brewed and criminals died upon the pillory.