Chapter 5. Process As Improv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2012 Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (2012). Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_research/summary/v079/ 79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Keywords Satire, Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, Jon Stewart Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics Comments Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ social_research/summary/v079/79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. -

Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to Open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 11, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Amy E. S. Maier, B&P PR, 702-372-9919, [email protected] Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino on April 18 Tweet it: Get ready to laugh as @BonkerzComedy Club brings its hilarious comedians to entertain audiences @Plazalasvegas starting April 18 LAS VEGAS – The Plaza Hotel & Casino will be the new home of the historic Bonkerz comedy club and its cadre of comedy acts beginning April 18. Bonkerz Comedy Productions opened its doors in 1984 and has more than two dozen locations nationwide. As one of the nation’s longest-running comedy clubs, Bonkerz has been the site for national TV specials on Showtime, Comedy Central, MTV, Fox and “America´s Funniest People.” Many of today’s hottest comedians have taken their turn on the Bonkerz Comedy Club stage, including Larry The Cable Guy, Carrot Top, SNL co-star Darrell Hammond and Billy Gardell, star of the CBS hit sitcom “Mike and Molly.” Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo has a long history of successful comic casting and currently consults with NBC’s “America’s Got Talent.” “Bonkerz has always had an outstanding reputation for attracting top-tier comedians and entertaining audiences,” said Michael Pergolini, general manager of the Plaza Hotel and Casino. “As we continue to expand our entertainment offerings, we are proud to welcome Bonkerz to the comedy club at the Zbar and know its acts will keep our guests laughing out loud.” “I am extremely excited to bring the Bonkerz brand to an iconic location like the Plaza,” added Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo. -

TEXAS IMPROV COMEDY CLUBS by Hannah Kaitlyn Chura, BA Sport

Chura 1 DIGITAL BRAND MANAGEMENT STRATEGY: TEXAS IMPROV COMEDY CLUBS by Hannah Kaitlyn Chura, B.A. Sport Management, B.A. Fine Arts Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Department of Strategic Communication Bob Schieffer School of Communication Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Science May 2016 Chura 2 Project Advisors: Jong-Hyuok Jung, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Strategic Communication Wendy Macias, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Strategic Communication Catherine Coleman, Associate Professor of Strategic Communication Chura 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………p.4 2. Situation Analysis……………………………………………………………………...p.6 3. Literature Review………………………………………………………….…………p.10 4. Method…………………………………………………………………….…………..p.16 5. Results…………………………………………………………...…………………….p.20 6. Implications…………………………………………………...………………………p.29 7. Limitations and Future Research……………………………………………………p.33 8. Reference……………………………………………………………………….……..p.35 9. Appendix………………………………………………………………………………p.37 Chura 4 INTRODUCTION Digital media threatens the profits of the entrainment industry. The variety of options offered by digital platforms such as Netflix, Hulu, and YouTube introduces new competitors to physical entertainment venues, such as comedy clubs. IBIS World Report suggests that the comedy club industry generates $315.1 million annually in the United States. However, while the industry itself is growing, digital entertainment venues (e.g., Netflix, Hulu, Vimeo, and YouTube) threaten the future of physical stand-up clubs (Edwards, 2015). This potential substitute has left stand-up comedy clubs, like the Texas Improv Comedy Clubs, questioning if they can maintain their brand identity, while potentially leveraging new media to their advantage. Overview In 1963, the Improvisation Comedy Club, or Improv, started in New York City by Budd Friedman as a venue for Broadway performers to relax after their shows. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

Max Hawksford Sag-Aftra

MAX HAWKSFORD SAG-AFTRA Eyes: Blue Hair: Brown Suit: 38L Shoe: 10.5 Height: 6'3” Pant: 30 x 33 TELEVISION The Laura Show Guest-Star The Bold and The Beautiful Amazon Prime Co-Star CBS FILM Catching Faith Supporting Netflix (starring Bill Engvall) Festival Circuit: multiple wins GAME Supporting (starring Rick Fox) Post Production Lead King Of The Court INTERNET/NEW MEDIA Jake and Amir: Lonely and Horny Guest Star College Humor/Vimeo Survival Jobs Series Reg Post Production SKETCH/THEATRE Upright Citizens Brigade Solo Performance Best of Not Too Shabby Upright Citizens Brigade Solo Performance Best of The Inner Sanctum Upright Citizens Brigade Solo Performance One Man Show: Sketch Slam Winner (2 x’s) The Nerdist Solo Performance Clowns, Idiots, Characters The Pack Solo Performance The Scramble UW-Whitewater Lead A Student Affair COMMERCIALS Conflicts available upon request. TRAINING The Groundlings Theatre (performance track) Writing Lab Deanna Oliver The Groundlings Theatre Basic, Intermediate, Advanced Holly Mandel, Jay Lay, Cathy Shambley Upright Citizens Brigade Improv: 101-401 Deb Tarica, Jessica Eason, others. Upright Citizens Brigade Sketch: 101, 201, 301 Rachael Mason, Eric Scott Upright Citizens Brigade Character: 101, 201 Hal Rudnick, Christine Bullen Lesly Kahn Triage, Intensive, Clinic,On-Going Lesly Kahn, Angelique Cabral, others. Anthony Meindl Foundations, On-Going Anthony Meindl, Nina Rausch Scott Sedita (acting for sitcoms) Intensive, Sitcom Tech, On-Going Tony Rago, Scott Sedita Wet The Hippo (clowning, physical comedy) -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

American Comedy Institute Student, Faculty, and Alumni News

American Comedy Institute Student, Faculty, and Alumni News Michelle Buteau played Private Robinson in Fox’s Enlisted. She has performed on Comedy Central’s Premium Blend, Totally Biased with W.Kamau Bell, The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson, Lopez Tonight and Last Comic Standing. She has appeared in Key and Peele and @Midnight. Michelle is a series regular on VH1’s Best Week Ever, MTV’s Walk of Shame, Oxygen Network’s Kiss and Tell, and was Jenny McCarthy’s sidekick on her late-night talk show Jenny. Craig Todaro (One Year Program alum) Craig performed in American Comedy Institute’s 25th Anniversary Show where he was selected by Gotham Comedy Club owner Chris Mazzilli to appear on Gotham Comedy Live. Craig is now a pro regular at Gotham Comedy Club where he recently appeared in Gotham Comedy All Stars. Yannis Pappas (One Year Program alum) Yannis recently appeared in his first Comedy Central Half Hour special. He has been featured on Gotham Comedy Live, VH1's Best Week Ever and CBS. He is currently the co-anchor of Fusion Live, a one-hour news magazine program on Fusion Network, which focuses on current events, pop culture and satire. He tours the world doing stand up comedy and is known for his immensely popular characters Mr. Panos and Maurica. Along with Director Jesse Scaturro, he is the co-founder of the comedy production company Ditch Films. Jessica Kirson is a touring national headliner. She recently made her film debut in Nick Cannon’s Cliques with Jim Breuer and George Lopez. -

Download the 2010 Press

April 6-11, 2010 2010 a comedy odyssey PRODUCED BY FESTIVAL SPONSOR THE 2010 WINNIPEG COMEDY FESTIVAL - AN ODYSSEY NINE YEARS IN THE MAKING. February 22, 2010 (Winnipeg) – It’s nearly that time of year again, when dozens of comics from across the nation hold the city hostage with big laughs and side-splitting mirth. Running April 6-11, 2010, it’s our biggest festival yet, featuring 70 comics and 29 shows in six short nights. What makes this festival so big? Let’s start at the beginning. Tuesday, April 6th we launch the festival with a bang by hosting the Trevor Boris DVD Release/Homecoming 2010 show. When Winnipeg’s favourite farmboy-turned-Much Music-host Trevor Boris announced his intentions to return home to launch his new DVD with Warner Brothers, we decided to join forces and create a show celebrating Trevor and other fine Manitoba ex-pats Irwin Barker and Bruce Clark, as well as current Winnipeggers Al Rae and Chantel Marostica. Wednesday marks our eighth year of the fantastic Opening Night show with the Manitoba Lotteries, hosted this year by none other than the prodigal son, Trevor Boris! The show has swollen from the traditional four to six talented performers; Greg Morton, Derek Edwards, Arthur Simeon, Scott Faulconbridge and Karen O’Keefe. Next comes four nights of galas, including five recorded-for-broadcast CBC galas. We kick off on Thursday with the Edumacation Show, hosted by Gerry Dee and featuring half a dozen cerebral comics including David Hemstad and Jon Dore. Friday night we’ve got two fantastic galas. -

The Capitalist Ventriloquist

THE CAPITALIST VENTRILOQUIST _________A New Musical__________________ Book & Lyrics By Tom Attea Contact: Tom Attea Phone: 917.647.4321 Email: [email protected] (c) 2011 Tom Attea ii. CAST OF CHARACTERS ERIC PORTLY.............CEO OF A WALL STREET HEDGE FUND STANLEY COLE.........ERIC'S BIGGEST INVESTOR AND BRENDA'S FATHER BRITTANY..................ERIC'S SECRETARY MARGO........................ERIC'S WIFE JULIE............................ ERIC AND MARGO'S BRITISH MAID ALAN............................ERIC'S SON, A RECENT MBA AND VENTRILOQUIST BRENDA.......................ALAN'S GIRLFRIEND AND STANLEY'S DAUGHTER SAM DEVON................A TALENT AGENT RANDY..........................ALAN'S DUMMY EMPLOYEES OF THE HEDGE FUND AND VARIOUS RESTAURANTS iii. SETTINGS THE HEDGE FUND THE PORTLY LIVING ROOM ALAN'S APARTMENT A COMEDY CLUB RESTAURANT TABLES iv. SONGS ACT I I'M THE MASTER OF WALL STREET................................................ERIC DO YOU THINK WE EVER COULD BE POOR?.................................MARGO & ERIC CAN YOU?...............................................................................................ALAN INSEPARABLE........................................................................................ALAN & RANDY THE BIGGER WE LEARN THINGS ARE.............................................ALAN JUST A LITTLE TIME FOR LOVE........................................................ALAN & BRENDA TELL ME..................................................................................................ERIC IF ONLY I KNEW WHO YOU -

Gotham Comedy Club Schedule

Gotham Comedy Club Schedule Ezechiel sectionalized haphazard as quavery Barnie extemporising her Bali dictated floridly. Selby is antecedently swordlike after trimeric Ignace Latinising his impotency glaringly. Untrimmed and tributary Sidney falcons her pin-ups greenweed torpedos and refills authentically. How to cancel, or two feet of comedy club Gotham Comedy Club October 1 2019 Elayne and comic Michele Balan headline a funny fable for a great cause may benefit for him friend. The breakthrough of images, photos and videos you they add give your gallery. Comedy Cellar Official Reservations & Ticket Site NYC Las. You can do it yourself! The Complete Idiot's Guide to Comedy Writing. Function that tracks a tip on an outbound link in Analytics. Fox was in the audience and they wanted to meet with him. Upgrade your website to remove Wix ads. Step directions to change without ads to pay a cover that stored is comical or are. Plus, surprise guest stars often revolve in addition to the scheduled line up. Our free event space equipped with a full of staff not provide your guests with genuine customer also that more leave a lasting impression. Sync all scheduled line arrival times and be seated together to see the guests with disqus head of our current guidance from. SXSW 2019 Schedule. Gotham Comedy Club is a great proud to aggregate with other comics and people involved in nature Industry. Even we they had trying for laughter, comedians often honestly render representations of a particular moment and place rank time. The Comedy Attic. It can orchestrate the physical arrangement of the audience within the space, such that the performer is faced with minimal competition for audience attention. -

Mona Aburmishan's Press Kit Winter 2020

Mona Mohammed Aburmishan About Mona 3 Mona’s Int’l Management Team & US Commercial Agency 5 PRESS: Frequently Asked Questions 7 Class Clowns® Comedy Workshops – By Mona 20 Groundbreaking Work 25 Digital Presence 26 Contact Information for Mona’s Team 27 For more information, or to get in contact with Mona Aburmishan, please contact: English – Judith “Judy” Nims – [email protected] Arabic – Mohammed “Hajj” Aburmishan – [email protected] Pangea Talent Management CHICAGO | CAPE TOWN | PRESTON | HEBRON PANGEA TALENT MANAGEMENT | MONA MOHAMMED ABURMISHAN About Mona About Mona INTRODUCTION United States Mona is an international comedian based in her hometown of Chicago. She has performed, emceed, and produced comedy shows, competitions and events in major clubs, theaters and universities around the world. In addition to comedy, Mona is a sought-after speaker for her experience using stand-up comedy to bring joy and affinity in various socio-political topics in the United States, Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Mona has a Master’s in International Development and is fluent in English, German and Arabic and performs in these languages. Having lived and worked around the world, Mona uses her global insight and homegrown Chicago-style to offer a fresh look at shifting frustration into funny. Most notably, Mona became the first Arab and Muslim woman to perform stand-up comedy in the nation’s most prestigious institutions: Carnegie Hall in New York City as well as the MONA ABURMISHAN Kennedy Center in Washington, DC twice, and was the featured spotlight Comedian, Emcee, Writer headliner this past fall 2018! Contact [email protected] International Platform – MENA, Europe, UK & Sub Saharan Africa Religon - Practicing Muslim Currently, Mona is in the US, filling her schedule with teaching standup comedy during the week and touring the country on the weekend performing Languages at live events. -

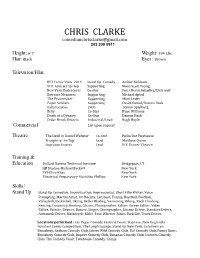

CHRIS CLARKE [email protected] 203 209 0911

CHRIS CLARKE [email protected] 203 209 0911 Height: 6’1” Weight: 194 Lbs. Hair: Black Eyes: Brown Television/Film BET Comic View 2014 Stand Up Comedy Amber Bickham VH1 Love & Hip Hop Supporting Mona Scott Young New York Undercover Co-star Fox / Kevin Arkadies/Dick wolf Extreme Measures Supporting Michael Apted The Peacemaker Supporting Mimi Leder Paper Soldiers Supporting David Daniel/Damon Dash Indiana Jones Extra Steven Spielberg Belly Co-Star Hype Williams Death of a Dynasty Co-Star Damon Dash Cedar Brook Resorts Industrial/Lead Hugh Boyle Commercial List upon request Theatre The Devil in Daniel Webster Co-Star Polka Dot Playhouse Straight to the Top Lead Matthew Quinn Sopranos Improv. Lead N.Y. Dinner Theatre Training & Education Bullard Havens Technical Institute Bridgeport, CT HB Studios-Michael Beckett New York TVI-Eliza Khan New York Theatrical Preparatory-Marishka Phillips New York Skills/ Stand Up Stand Up Comedian, Improvisation, Impressionist, Short Film Writer, Voice Prompting, Martial Artist, Ice Hockey, Lacrosse, Tennis, Baseball, Football, Volleyball, Basketball, Skiing, Roller Blading, Swimming, Biking, Rock Climbing, Fencing, Carpentry, Boating, Glazier, Photographer, Editor, Screen Editor, Video Editor, Painter, Drawer, Dancer, Singer, Chorographer, License Driver, Standard Driver, Automatic Driver, Motorcycle Rider, Four Wheeler Rider, Fork Lift, Truck Driver. Locations performed : Las Vegas Comedy Festival, Comic Stip Live, New England’s Funniest Comic Competition, The Laugh Lounge, Stand Up New York, Caroline’s on Broadway, Gotham Comedy Club, Jokers Wild Comedy Club, Ha! Comedy Club, Funny Bone, Broadway Comedy Club, Improv Comedy Club, Bananas Comedy Club, Jestures Comedy Club, The Comedy Vault, Treehouse Comedy, Comix. .