Contentious Comedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why YOU Should Be an English Major

Why YOU should be an English Major You’ll be able to communicate your ideas effectively. This is what employers want the most – people who can communicate clearly. Impress your employer with your ability to communicate, and you’ll get promoted. You’ll also sound smarter than everybody else. You’ll be able to learn new tasks and ideas. A liberal arts education teaches you how to learn, not how to do a specific job. Your employer will provide on-the-job training. Besides, the hot jobs of 20 years from now haven’t even been thought of yet; major in English, learn how to learn new job skills, and stay employed. You’ll be prepared for med school, law school, business school… Being an English major teaches you how to think critically. Graduate schools in every field are more interested in your ability to analyze situations and make connections between concepts than in your ability to memorize lists. You’ll get a good job. Major scientific, technological, industrial, and financial companies like to hire English majors. They want employees who can analyze problems, think up creative answers, and communicate those answers to coworkers. And an English degree teaches you to do all these things. You’ll earn lots of money. Well, maybe not as much as science graduates, but the 201 201 Payscale College Salary Report listed salaries for popular careers for English majors that ranged from $ to $ . 5- 6 40,000 76,000 You’ll move up the company ladder. Your English major taught you how to analyze problems, think creatively, synthesize intelligent solutions, and communicate those solutions to your bosses and coworkers. -

How Does Context Shape Comedy As a Successful Social Criticism As Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’S SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2012 How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?” Abigail Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Abigail, "How Does Context Shape Comedy as a Successful Social Criticism as Demonstrated by Eddie Murphy’s SNL Sketch “White Like Me?”" (2012). Honors College. 58. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/58 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW DOES CONTEXT SHAPE COMEDY AS A SUCCESSFUL SOCIAL CRITICISM AS DEMONSTRATED BY EDDIE MURPHY’S SNL SKETCH “WHITE LIKE ME?” by Abigail Jones A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Communications) The Honors College University of Maine May 2012 Advisory Committee: Nathan E. Stormer, Professor of Communication, Advisor Kristin M. Langellier, Professor of Communication Sandra Hardy, Associate Professor of Theater Mimi Killinger, Honors College Rezendes Preceptor for the Arts Adam Kuykendall, Marketing Manager for the School of Performing Arts Abstract This thesis explores the theory of comedy as social criticism through an interpretive investigation. For comedy to be a potent criticism it is important for the audience to understand the context surrounding the sketch. Without understanding the context the sketch still has the ability to be humorous, but the critique is harder to acknowledge. -

American Comedy in Three Centuries the Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile

American Comedy in Three CenturieS The Contras4 Fashion, Calzforniα Suile James R. Bowers Abstract This paper is a survey of the development of American comedy since the United States became an independent nation. A representative play was selected from the 18th century(Royall Tyler’s The Contrast), the 19th century(Anna Cora Mowatt’s Fashion)and the 20th century(Neil Simon’s Califoグnia Suite). Asummary of each play is丘rst presented and then fo110wed by an analysis to determine in what ways it meets or deviates from W. D, Howarth’s minimal de且nition of comedy. Each work was found to conform to the definition and to possess features su岱ciently distinct for it to be classified as a masterpiece of its time. Next, the works were analyzed to derive from them unique features of American comedy. The plays were found to possess distinctive elements of theme, form and technique which serve to distinguish them as Ameri. can comedies rather than Europeal1, Two of these elelnents, a thematic concern with identity as Americans and the technical primacy of dialog and repartee for the stimulation of laughter were found to persist into present day comedy. Other elements:characterization, subtlety of form -145一 and social relevance of theme were 6bserved to have evolved over the centuries into more complex modes. Finally, it was noted that although the dominant form of comedy iロthe 18th and 19th centuries was an American variant of the comedy of man- ners, the 20th century representative Neil Simon seems to be evolving a new form I have coined the comedy -

NATPE 2013 Tuesday, January 29, 2013 Click For

join the family this fall 20TH TV 3376 BRIAN S. TOP HAT BANNER MECHANICAL BUILT AT 100% MECH@ 100% 9.875" X 1.25" 9.625"W X 1"H SHOW DAILY NATPE • MIAMI BEACH TUESDAY, JANUARY 29, 2013 CONTENT INDUSTRY client and prod special info: # job# artist issue/ time pub post date (est) insert/ line Sinead Harte size air date screen 323-963-5199 ext 220 CHANGE 8240 Sunset Blvd CREATES bleed trim live Los Angeles, CA 90046 DEBATEBY ANDREA FREYGANG CERTAINBY CHARLOTTE LIBOV ideo might have killed ra - dio, as the first song aired on echnology is changing view- VMTV implied, but not every- ing habits and the TV industry one is certain that the internet is Tmust keep pace by reinventing going to cause TV’s demise. In itself, much as music industry did the opening session of NATPE, in the wake of the seismic changes as panelists debated the impact that nearly destroyed that indus- of social media and the internet try, observed David Pakman, who on the TV industry, audience re- led the opening panelA-004 at NATPE 1537F CHRISTINA SCHIERMANN PHOTO BY ALEX MATTEO BY PHOTO 1/4"=1' action was mixed. on Monday. Game changing or not? That was the topic under consideration Monday when a keynote panel of LAX FLIGHT PATH 9.01.08 N/A 4c “I think Facebook is a better experts voiced opinions about the impact of digital distribution. Among those weighing in were, In answer to the question competitor to TV than YouTube. from left to right, Kevin Beggs, Lionsgate Television Group president; TheBlaze’s Betsy Morgan, Will Disruption Choke250' the w TeleviX 65'- h 9.18.08 SUNDAY 150 It’s a very interesting debate president & chief strategy officer; and Aereo’s Chet Kanojia, founder and CEO sion Business Models?,68.75" the Xpanel 17.875" 62.5" X 16.25" ALL to have,” said Fiona Dawson, a SEE CHANGE, P. -

Production Biographies

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES MIKE O’MALLEY (Executive Producer & Showrunner, Writer- 201, 207, 210) Truly a multi-hyphenate, Mike O’Malley got his start in front of the camera hosting Nickelodeon’s “Get the Picture” and the iconic game show “Guts”. His success continued in television with standout roles in “Yes Dear”, “My Name Is Earl”, “My Own Worst Enemy”, “Justified”, and his Emmy®-nominated, groundbreaking performance as ‘Burt Hummel’ on the hit show “Glee”. Mike’s feature work includes roles in Eat Pray Love, Cedar Rapids, Leatherheads, Meet Dave, 28 Days, and the upcoming Untitled Concussion Project starring Will Smith which will be released Christmas 2015. Also an accomplished writer, Mike wrote and produced the independent feature Certainty which he adapted from his own play. In television, Mike has served as a Consulting Producer on “Shameless” and is in his second season as creator and Executive Producer of “Survivor’s Remorse” for Starz. LEBRON JAMES (Executive Producer) LeBron James is widely considered one of the greatest athletes of his generation. James’ extraordinary basketball skills and dedication to the game have won him the admiration of fans across the globe, and have made him an international icon. Prior to the 2014-2015 season, James returned to his hometown in Ohio and rejoined the Cleveland Cavaliers in their mission to bring a championship to the community he grew up in. James had previously spent seven seasons in Cleveland after being drafted out of high school by his hometown team with the first overall pick in the 2003 NBA Draft. James led the Cavaliers to five straight NBA playoff appearances and earned six All-Star selections during his first stint in Cleveland. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a -

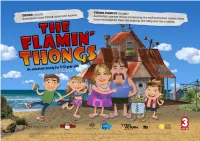

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

Presents a Film by Michael Winterbottom 104 Mins, UK, 2019

Presents GREED A film by Michael Winterbottom 104 mins, UK, 2019 Language: English Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 217 – 136 Geary Ave Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Synopsis GREED tells the story of self-made British billionaire Sir Richard McCreadie (Steve Coogan), whose retail empire is in crisis. For 30 years he has ruled the world of retail fashion – bringing the high street to the catwalk and the catwalk to the high street – but after a damaging public inquiry, his image is tarnished. To save his reputation, he decides to bounce back with a highly publicized and extravagant party celebrating his 60th birthday on the Greek island of Mykonos. A satire on the grotesque inequality of wealth in the fashion industry, the film sees McCreadie’s rise and fall through the eyes of his biographer, Nick (David Mitchell). Cast SIR RICHARD MCCREADIE STEVE COOGAN SAMANTHA ISLA FISHER MARGARET SHIRLEY HENDERSON NICK DAVID MITCHELL FINN ASA BUTTERFIELD AMANDA DINITA GOHIL LILY SOPHIE COOKSON YOUNG RICHARD MCCREADIE JAMIE BLACKLEY NAOMI SHANINA SHAIK JULES JONNY SWEET MELANIE SARAH SOLEMANI SAM TIM KEY FRANK THE LION TAMER ASIM CHAUDHRY FABIAN OLLIE LOCKE CATHY PEARL MACKIE KAREEM KAREEM ALKABBANI Crew DIRECTOR MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM SCREENWRITER MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM ADDITIONAL MATERIAL SEAN GRAY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER DANIEL BATTSEK EXECUTIVE PRODUCER OLLIE MADDEN PRODUCER -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

The Acid House a Film by Paul Mcguigan

100% PURE UNCUT IRVINE WELSH The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan based on the short stories from “The Acid House” by Irvine Welsh Starring Ewen Bremner Kevin McKidd Maurice Roëves Martin Clunes Jemma Redgrave Introducing Stephen McCole Michelle Gomez Arlene Cockburn Gary McCormack Directed by Paul McGuigan Screenplay by Irvine Welsh Director of Photography Alasdair Walker Editor Andrew Hulme Costume Designers Pam Tait & Lynn Aitken Production Designers Richard Bridgland & Mike Gunn Associate Producer Carolynne Sinclair Kidd Produced by David Muir & Alex Usborne FilmFour presents a Picture Palace North / Umbrella Production produced in association with the Scottish Arts Council National Lottery Fund, the Glasgow Film Fund and the Yorkshire Media Production Agency UK • 1999 • 112 mins • Color • 35mm In English with English subtitles Dolby Surround Sound a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan Paul McGuigan’s THE ACID HOUSE is a surreal triptych adapted by Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh from his collection of short stories. Combining a vicious sense of humor with hard- talking drama, the film reaches into the hearts and minds of the chemical generation, casting a dark and unholy light into the hidden corners of the human psyche. Part One The Granton Star Cause The first film of the trilogy is a black comedy of revenge, soccer and religion that come together in one explosive story. Boab Coyle (STEPHEN McCOLE) thinks he has it all, a ‘tidy’ bird, a job, a cushy number living at home with his parents and a place on the kick-about soccer team the Granton Star. -

Top 3 Reasons British TV Is the Best | Mismatched Pear OCT NOV DEC ⍰ ❎ 1 Capture 05 F 5 Nov 2016 2015 2016 2017 ▾ About This Capture

Top 3 Reasons British TV is the Best | MisMatched Pear OCT NOV DEC 1 capture 05 f 5 Nov 2016 2015 2016 2017 About this capture A picture is worth what? Stuff You Didn't Know! Watch Out or You May End... Origins: The Oldest Use of the... Nearly 2 days ago Nearly 4 days ago STUFF YOU DIDN’T KNOW! ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT A PICTURE IS WORTH WHAT? What Straight People Can Do to Actually Support the LGBT Community Stuff You Didn't Know! Hazel Romano Top 3 Reasons British TV is the Best Vids 1 month ago • Jason Eisenberg https://web.archive.org/web/20161105051857/http://mismatchedpear.com/top-3-reasons-british-tv-is-the-best/[3/3/2018 3:39:58 PM] Top 3 Reasons British TV is the Best | MisMatched Pear 10 YouTube Channels That’s Ousted TV Sketch Shows 5 Cooking Products that Retard Your Ability to Cook http://www.westernsun.us Although statistics tell us that fewer and fewer people are watching TV, much of it is due to the amount of programming now available to us directly. With the rise of online video 5 Feminist YouTube Channels You Should Be Watching services like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, we can watch virtually any program we want at any time. You don’t have to be glued to your television at a specific time to watch an episode of your favorite show, and in many cases you don’t even have to set your DVR. If you purchase a season pass for your favorite show on Amazon or through iTunes, you can watch episodes at your leisure or as soon as they air.