Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards a Philosophy of The

Toward a Philosophy ofthe Act MICHAEL HOLQUIST. • • • • • • • • TOWARD A PHILOSOPHY OF THE ACT····· UNIVERSITY OF TfXAS PRfSS SLAVIC SERIES, NO. 10 MICHAEL HOLQUIST General Editor M. M. BAKHTIN TOWARDA PHILOSOPHY OF THE ACT TRANSLATION AND NOTES BY VADIM LIAPUNOV EDITEDBY VADIM LIAPUNOV & MICHAEL HOLQUIST UN I V E R SIT Y 0 F T E X ASP RES S, AU S TIN ••••••••••• Cop\'right © 1993 lw the L'niversit\, of Texas Press All rights reser\'ed Printed in the United St,nes of AmeriCl Third paperback printing, 1999 Requests te)r permission to reproduce m,nerial trom this work should be sent to Permissions, Universit\' of Texas Press, Box -819, Austin, TX -8-15--819, @ The paper used in this publiCltion meets the minimum requirements of American ;-.Jeltion,,1 StaIlli.lrd te)r Inte1rl1ution Sciences-Pernunence of P,'per te)r Printed Librar\, Materi"ls, ANSI Zj9,+8- 198+, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLlCATION DATA Bakhtin, M, ,\1. (Mikh,lil 189,-19-', I K tilosotii poStlIpk.1, English I Toward a philosophl' of the ,lct / lw Bakhtin ; transLnion ,md notes b\' V,ldim Liap"n{)\' ; edited bl' \',ldim Li,lp"no\' ,1I1d Michael HolqlIisL - 1St cd, p, cm, - (L' nil'ersit\' of 'I'ex, IS Press SLn'ic series; no, 10) Incilides bibliogr,lphical reterences ,1I1d index, ISBN 0-292--653+--, - ISBN 0-292--0805-X (pbk,) L Act (Philosophl') 2, Ethics, " Commlinication-l\\oral ,1I1d ethic,ll aspects, +, Literelture-Philosophl', I. Li,lpUn()\', V,ldim, 193,'- II. Holquist, Michael, 193'- Ill. Title. 1\', Series, BI05,A35 B3+13 1993 128' ,4-dc20 93--'5- • • • • • • • • CONTENTS FOREWORD (fll MICHAEL HOLQUIST TRANSLATORJS PREFACE VADIM LIAPUNOV INTRODUCTION TO THE RUSSIAN EDITION ,x;xi s. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Handbook for One-Act Play

Notice of Non-Discrimination “In a well-planned One-Act Play Contest, there are no losers.” The University Interscholastic League (UIL) does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, disability, or age in its programs. See Section 360, Non-Discrimination Policy, UIL Constitution and Contest Rules. https://www.uiltexas.org/policy/constitution/general/nondiscrimination Handbook The following person has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-dis- crimination policies: Dr. Mark Cousins for University Interscholastic League Director of Compliance and Education 1701 Manor Road, Austin, TX 78722 Telephone: (512) 471-5883 Email: [email protected] One-Act Play For further information on notice of non-discrimination, visit http://wdcrobcolp01. ed.gov/CFAPPS/OCR/contactus.cfm or call 1-800-421-3481 or contact OCR in Dallas, Texas: AMENDED Office for Civil Rights U.S. Department of Education 1999 Bryan Street, Dallas, TX 75201-6810 Telephone: 214-661-9600, Fax: 214-661-9587, TDD: 800-877-8339 25th Edition Email: [email protected] For further information write: State Theatre Director University Interscholastic League 1701 Manor Road Austin, Texas 78722 512/471-9996 or 471-4517 (Office), 512/471-7388 (Fax) 512/471-5883 (MAIN UIL SWITCHBOARD) E-MAIL: [email protected] UIL WEB: www.uiltexas.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A very sincere thanks to Connie McMillan and to Elisabeth Sikes for their contributions. I also wish to thank the Texas Theatre Adjudicators and Officials (TTAO) and the UIL Theatre Advisory Committee for their work on this edition. The League also wishes to thank the Texas Educational Theatre Associa- tion, Inc. -

The Structure of Plays

n the previous chapters, you explored activities preparing you to inter- I pret and develop a role from a playwright’s script. You used imagina- tion, concentration, observation, sensory recall, and movement to become aware of your personal resources. You used vocal exercises to prepare your voice for creative vocal expression. Improvisation and characterization activities provided opportunities for you to explore simple character portrayal and plot development. All of these activities were preparatory techniques for acting. Now you are ready to bring a character from the written page to the stage. The Structure of Plays LESSON OBJECTIVES ◆ Understand the dramatic structure of a play. 1 ◆ Recognize several types of plays. ◆ Understand how a play is organized. Much of an actor’s time is spent working from materials written by playwrights. You have probably read plays in your language arts classes. Thus, you probably already know that a play is a story written in dia- s a class, play a short logue form to be acted out by actors before a live audience as if it were A game of charades. Use the titles of plays and musicals or real life. the names of famous actors. Other forms of literature, such as short stories and novels, are writ- ten in prose form and are not intended to be acted out. Poetry also dif- fers from plays in that poetry is arranged in lines and verses and is not written to be performed. ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ These students are bringing literature to life in much the same way that Aristotle first described drama over 2,000 years ago. -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to Open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 11, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Amy E. S. Maier, B&P PR, 702-372-9919, [email protected] Legendary Bonkerz Comedy Club to open at the Plaza Hotel & Casino on April 18 Tweet it: Get ready to laugh as @BonkerzComedy Club brings its hilarious comedians to entertain audiences @Plazalasvegas starting April 18 LAS VEGAS – The Plaza Hotel & Casino will be the new home of the historic Bonkerz comedy club and its cadre of comedy acts beginning April 18. Bonkerz Comedy Productions opened its doors in 1984 and has more than two dozen locations nationwide. As one of the nation’s longest-running comedy clubs, Bonkerz has been the site for national TV specials on Showtime, Comedy Central, MTV, Fox and “America´s Funniest People.” Many of today’s hottest comedians have taken their turn on the Bonkerz Comedy Club stage, including Larry The Cable Guy, Carrot Top, SNL co-star Darrell Hammond and Billy Gardell, star of the CBS hit sitcom “Mike and Molly.” Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo has a long history of successful comic casting and currently consults with NBC’s “America’s Got Talent.” “Bonkerz has always had an outstanding reputation for attracting top-tier comedians and entertaining audiences,” said Michael Pergolini, general manager of the Plaza Hotel and Casino. “As we continue to expand our entertainment offerings, we are proud to welcome Bonkerz to the comedy club at the Zbar and know its acts will keep our guests laughing out loud.” “I am extremely excited to bring the Bonkerz brand to an iconic location like the Plaza,” added Bonkerz owner Joe Sanfelippo. -

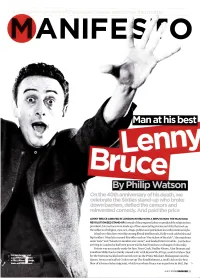

Lenny Bruce Arrived in London in 1962 with a Reputation: the Man Who Revolutionised Stand-Up

NIFE 'rrO ,,1,::l!1,'w n fi+I m"* Effi;- l.-i; lw}atr-|tr 'lti.,lx{t ' -- : . '.' :'. : .' . ^- ': ' .. ,: -rt,' '."' .. tll :^ :i:ji ""-"-, ::-- -':- LENNY BRUCE ARRIVED IN LONDON IN 1962 WITH A REPUTATION: THE MAN WHO REVOLUTIONISED STAND-UP. Instead ofthe preparedjokes on predictable subjects then prevalent, his routines were made up offree-associating stories and skits that took on the subjects ofreligion, race, sex, drugs, politics ar-rd patriotism in confrontational style. It had won him hero worship amongliberal intellectuals, Holly.wood celebrities and hip insiders. It had also earned him titles such as "the sickest ofthe sick", "the man from outer taste" and "America's number one vomic", and landed him in trouble - justbefore arrivingin London he had been put on trial in San Francisco on charges ofobscenity. Britainwas not exactlyready for him. Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonatharr Miller had certainly caused a stir withBeyondthe Frlnge, a satirical show that for the firsttime tackled such sacred cows as the Prime Minister, Shakespeare and the Queen. Its success had led Cook to set up The Establishmen! a smal1 club on the first floorofaformerSohostripjoint,whichwaswhereBr-ucewastoperforminlg62.Btt ) JULY 2006 ESOUIRE 5] At,HI'3 t t Ol rn,J!, .tu5 Booed offt Apdl 1963, Brue the countqr as awhole was in grip still the ofpost-war Conservative austerity; is retused entry to Britain the Sixties had notyet started swinging. Cook and his cohorts were thrilled becaus it would "not b€ in tfte public interest". Beror, and awed by Br-uce's fearless and freewheelingbrand of sharp-tongued, with his wife, Honey, and foul-mouthed comedy. -

Comedy and the Constitution: the Legacy of Lenny Bruce

H-Law Comedy and the Constitution: The Legacy of Lenny Bruce Discussion published by Charity Adams on Wednesday, March 16, 2016 Type: Call for Papers Date: October 27, 2016 to October 28, 2016 Location: Massachusetts, United States Subject Fields: American History / Studies, Jewish History / Studies, Graduate Studies, Communication The American Studies Program and the Robert D. Farber University Archives and Special Collections Department at Brandeis University are pleased to announce a conference scheduled for October 27-28, 2016, to evaluate the legacy of comedian Lenny Bruce. His corrosive and transgressive satire as well as his boldness in pushing the envelope of the laws of obscenity have made him an iconic figure in American culture. In March 2014, the Special Collections Department at Brandeis University acquired Bruce’s papers from his daughter, Kitty Bruce, who is scheduled to attend the conference on campus. “Comedy and the Constitution” will coincide with the formal opening of this collection of archival material associated with the most influential American comedian of the post–World War II era. We invite interested participants to submit proposals for individual papers or pre-constituted panels. For each paper, email (as separate attachments) a 150-200-word abstract, along with a brief biographical note, to [email protected]. The deadline for proposals is April 11, 2016. Topics may include but need not be limited to: the nature of obscenity; aspects of Bruce’s work (LPs, nightclubs, television, autobiography); First Amendment rights; Jewish humor; Cold War culture; the transformations of the 1960s; and Bruce’s comedic predecessors, contemporaries, and descendants. Contact Info: Charity Adams, Brandeis University Email: [email protected] Telephone: (781) 736-3030 Contact Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.brandeis.edu/programs/american-studies/Bruce2016.html Citation: Charity Adams. -

Lenny Bruce Without Tears Author(S): Neil Schaeffer Source: College English, Vol

Lenny Bruce without Tears Author(s): Neil Schaeffer Source: College English, Vol. 37, No. 6 (Feb., 1976), pp. 562-577 Published by: National Council of Teachers of English Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/376149 Accessed: 14/01/2009 15:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ncte. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. National Council of Teachers of English is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to College English. http://www.jstor.org NEIL SCHAEFFER Lenny Bruce without Tears CAN YOU SHOUT"Fuck!" in a crowded nightclub? Maybe it would be all right if you were an etymologist, though professors ought not shout. -

This Is No Laughing Matter: How Should Comedians Be Able to Protect Their Jokes?

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 42 Number 2 Summer 2020 Article 3 Summer 2020 This is No laughing Matter: How Should Comedians Be Able to Protect Their Jokes? Sarah Gamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Sarah Gamblin, This is No laughing Matter: How Should Comedians Be Able to Protect Their Jokes?, 42 HASTINGS COMM. & ENT. L.J. 141 (2020). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol42/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 - GAMBLIN_CMT_V42-2 (DO NOT DELETE) 4/8/2020 11:18 AM This is No laughing Matter: How Should Comedians Be Able to Protect Their Jokes? by SARAH GAMBLIN1 The only honest art form is laughter, comedy. You can’t fake it . try to fake three laughs in an hour—ha ha ha ha ha—they’ll take you away, man. You can’t.2 – Lenny Bruce Abstract This note will discuss the current state of protection for jokes and comedy. As it is now, the only protection comics have is self-help, meaning comedians take punishing thefts into their own hands. This note will dive into the reasons why the current legislature and courts refuse to recognize jokes as copyrightable. -

Censorship in Social Media: Political Satire and the Internet's

Research Article Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences Censorship In Social Media: Political Satire and the Internet’s “Oppositionists” Markella Elpida Tsichla *Corresponding author: Markella Elpida Tsichla, University of Patras, Greece. E-mail: milpap@ University of Patras, Greece hist.auth.gr Submitted: 11 Nov 2019; Accepted: 23 Nov 2019; Published: 03 Jan 2020 Abstract Censorship has been prevalent through time in various forms, at different historical periods all over the world. It is negatively perceived, and it is considered to undermine democracy and violate human rights. As a rule, it is a feature that characterises conservative societies, totalitarian regimes, as well as individuals with ideological preconceptions. The areas mostly affected by it include freedom of expression and free movement of ideas. Governments try to ward themselves against this phenomenon in various manners, in particular by establishing laws that protect human goods and moral values, as those have been shaped from the Age of Enlightenment onwards. However, in recent years, in the midst of the rapid dissemination of technology and the swift development of social media, a tendency has emerged consisting in trying to influence the unsuspecting public opinion and resulting in excluding from the public sphere opinions which are not pleasant to part of the media users, often serving “external” interests. Therefore, the online medium, free par excellence and offering, in principle, the possibility to everyone to publicly and courageously express their opinions, hinders and becomes an obstacle to the dissemination of “another” opinion, in spite of this dissemination being the ultimate intellectual feature of contemporary societies. This type of censorship has now been included in the long list of the many aspects of the phenomenon seen to this day. -

Lenny Bruce Further Study

LENNY BRUCE FURTHER STUDY Description: Performing from the late 40’s up to his death in 1966, Lenny has left behind a collection of work that goes beyond what we could cover in the available class time. A deeper look at Lenny Bruce can be seen in his albums, movies, books and TV appearances, as well as in the documentary tributes and biopics on him. The following are some links and resources for further study. Note: The material in the Amazon.com links listed here, in many cases, can also be obtained from your local library or other sources. Materials: Lenny Bruce Albums If you only listen to one Lenny Bruce album, “Bits I Got Busted For” or the “Carnegie Hall” are recommended. Of course, all are recommended, they all have value and enrich the Lenny experience. Click on the blue links below to see the Amazon.com writeups of each album. Most of these albums are also available at your local library. Year Title Label Format Notes 2 tracks feature Henry Jacobs & Interviews of Our LP / LP 1969 / CD Woody Leifer, liner notes by 1958 Times 1991 / download Horace Sprott III & Sleepy John Estes LP / LP / 8-track 1984 The Sick Humor of 1959 / CD 1991, 2012 & Lenny Bruce Fantasy 2017 / download 2010 Records I Am Not a Nut, Elect LP / CD 1991 / Liner notes by Ralph J. Gleason 1960 Me! (Togetherness) download LP / CD 1991, 2013 & 1961 American 2016 / download Lenny Bruce Is Out Lenny Self-published live recordings 1964 LP / download 2004 Again Bruce from 1958–1963 Please submit any questions to: [email protected] Lenny Bruce Is Out