PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imaginationland," Terrorism, and the Difference Between Real And

Christopher C. Kirby, PhD. Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA. 99004 “IMAGINATIONLAND,” TERRORISM, AND THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN REAL AND IMAGINARY CHRISTOPHER C. KIRBY Eastern Washington University “Ladies and gentlemen, I have dire news. Yesterday, at approximately 18:00 hours, terrorists successfully attacked... our imagination”1 “Imaginationland” was an Emmy winning, three-part story which aired as the tenth, eleventh and twelfth episodes of South Park’s eleventh season and was later re-issued as a movie with all of the deleted scenes included. The story begins with the boys waiting in the woods for a leprechaun that Cartman claims to have seen. Kyle, ever the skeptic, has bet ten dollars against sucking Cartman’s balls that leprechauns aren’t real. When the boys finally trap one, to Kyle’s shock and dismay, it cryptically warns of a terrorist attack and disappears. That night at the dinner table Kyle asks his parents where leprechauns come from and why one would visit South Park to warn of a terrorist attack. They chide him for not knowing the difference between real and imaginary and he mutters, “I thought I did.” What ensues is pure South Park genius as we discover that, in fact, nobody seems to know what the difference is. As the story unfolds it’s obvious that no one will be safe, as the episode lampoons the U.S. “war on terror,” the American legal system, Hollywood directors, the media, Christianity, the military, Kurt Russell, and Al Gore’s campaign against climate change [ManBearPig is real… I’m super cereal!] all the while reminding us that imagination is an essential feature of human life. -

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

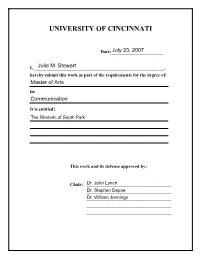

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Stream South Park Online Free No Download Stream South Park Online Free No Download

stream south park online free no download Stream south park online free no download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbdf08ddb7c40b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Stream south park online free no download. Watch full episodes of your favorite shows with the Comedy Central app.. Enjoy South Park, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Broad City and many more, . New episodes of “South Park” will now go through many windows — on television on Comedy Central, on the web at SouthParkStudios for . How to watch South Park on South Park Studios: · Go to: http://southpark.cc.com/.. · Select “Full episodes” from the top menu.. south park episodes. South Park Zone South Park Season 23.. Watch all South Park episodes from Season 23 online . "Mexican Joker" is the first episode of the twenty-third season of . seasons from many popular shows exclusively streaming on Hulu including Seinfeld, Fargo, South Park and Fear the Walking Dead. -

Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross

Excremental Ecstasy, Divine Defecation and Revolting Reception: Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross Scatology, for all the sordid formidability the term evokes, is not an es- pecially novel or unusual theme, stylistic technique or descriptor in film or filmic reception. Shit happens – to emphasise both the banality and perva- siveness of the cliché itself – on multiple levels of textuality, manifesting it- self in both the content and aesthetic of cinematic texts, and the ways we respond to them. We often refer to “shit films,” using an excremental vo- cabulary redolent of detritus, malaise and uncleanliness to denote their otherness and “badness”. That is, films of questionable taste, aesthetics, or value, are frequently delineated and defined by the defecatory: we describe them as “trash”, “crap”, “filth”, “sewerage”, “shithouse”. When considering cinematic purviews such as the b-film, exploitation, and shock or trash filmmaking, whose narratives are so often played out on the site of the gro- tesque body, a screenscape spectacularly splattered with bodily excess and waste is de rigeur. Here, the scatological is both often on blatant dis- play – shit is ejected, consumed, smeared, slung – and underpining or tinc- turing form and style, imbuing the text with a “shitty” aesthetic. In these kinds of films – which, as their various appellations tend to suggest, are de- fined themselves by their association with marginality, excess and trash, the underground, and the illicit – the abject body and its excretia not only act as a dominant visual landscape, but provide a kind of somatic, faecal COLLOQUY text theory critique 18 (2009). -

HBO Max Will Be More Expensive Than Netflix, Disney Or Apple

HBO Max will be more expensive than Netflix, Disney or Apple. Does that mean it'll be a tough sell? 31 October 2019, by Jefferson Graham Now try $14.99 monthly for HBO Max. That's not a misprint. The most popular tier on Netflix, which has been streaming since 2013 and is the undisputed leader in the field, is $12.99. For your $15, Warner is giving you a lot: Some 10,000 hours of content, new and old fare from the libraries of Warner Bros., HBO, CNN, TNT, TBS, the Cartoon Network, Adult Swim, Turner Classic Movies and DC Comics. Warner announced a giant slate of projects, including a prequel to HBO's Game of Thrones, Credit: CC0 Public Domain new movies with Reese Witherspoon and Meryl Streep, revivals of the classic Looney Tunes (Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig) cartoons and a new series featuring the Hanna Barbera characters (The Welcome to the hard sell. Flintstones, Jetsons, Yogi Bear, Mr. Jinx) called "Jellystone." HBO Max won't debut until May, but AT&T's Warner Media wanted to get a quick attention grab The complete seasons of "South Park," "Friends" on consumers during a week that will see Apple and "The Big Bang Theory" are coming to HBO enter the streaming wars and Disney join two Max, along with dozens of movies from the Warner weeks later. Bros. library, everything from the "Joker" and "Batman" movies to "Casablanca" and both the HBO staged a giant presentation on a historic Judy Garland and Lady Gaga versions of "A Star Is soundstage at the Warner Bros. -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2012 Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Ralph M. Rosen University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Rosen, R. M. (2012). Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_research/summary/v079/ 79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. Reprinted with permission by The Johns Hopkins University Press. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/33 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modernolitical P Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart Keywords Satire, Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, Jon Stewart Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics Comments Rosen, Ralph M. "Efficacy and Meaning in Ancient and Modern Political Satire: Aristophanes, Lenny Bruce, and Jon Stewart." Social Research 79.1 (Spring 2012): 1-32. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ social_research/summary/v079/79.1.rosen.html Copyright © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press. This article first appeared in Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 79, Issue 1, Spring, 2012, pages 1-32. -

Karaoke by Keysdan Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird'

Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Addicted To Spuds 'Weird' Al Yankovic Alimony 'Weird' Al Yankovic Amish Paradise 'Weird' Al Yankovic Another Rides The Bus 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Eat It 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ebay 'Weird' Al Yankovic Fat 'Weird' Al Yankovic Grapefruit Diet 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Lost On Jeopardy 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Love Rocky Road 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Want A New Duck 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic My Bologna 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Phony Calls 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ricky 'Weird' Al Yankovic Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic She Drives Like Crazy 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Spam 'Weird' Al Yankovic The Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic Yoda 'Weird' Al Yankovic You Don't Love Me Anymore 2 Live Crew Me So Horny Adam Sandler At A Medium Pace (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Adam Sandler Ode To My Car (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Piece Of S--t Car Adam Sandler What The H--- Happened To Me Adam Sandler What The Hell Happened To Me www.KeysDAN.com 501.470.6386 Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Bill Clinton Parody Bimbo No.5 Britney Spears Parody Oops I Farted Again CLEDUS T JUDD MY CELLMATE THINKS I'M SEXY Cheech & Chong Earache My Eye Chef Chocolate Salty Balls Chef Love Gravy Chef No Substitute, Oh Kathy Lee Chef Simultaneous Chef & Meatloaf Tonight Is Right for Love Chef & No Substitute Oh Kathy Lee Chef (South Park) Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised.